Archive

What’s Next?

I was browsing through some old powerpoint pitches and I cam across this potentially share-worthy graphic:

I’m sorry for the poor resolution. I was too lazy to spruce it up.

Bankrupt Models

In his paper, “The Dispute Over Control Theory“, Bill Powers tries to clarify how Perceptual Control Theory (PCT) differs from the two main causal approaches to psychology: stimulus-response and command-response. In order to gain a deeper understanding of PCT, I’m gonna try to reproduce Bill’s argument in this post with my own words and pictures.

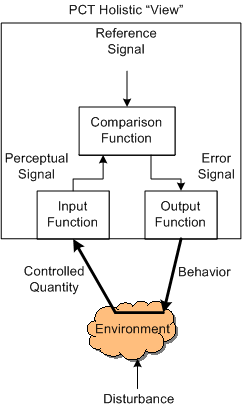

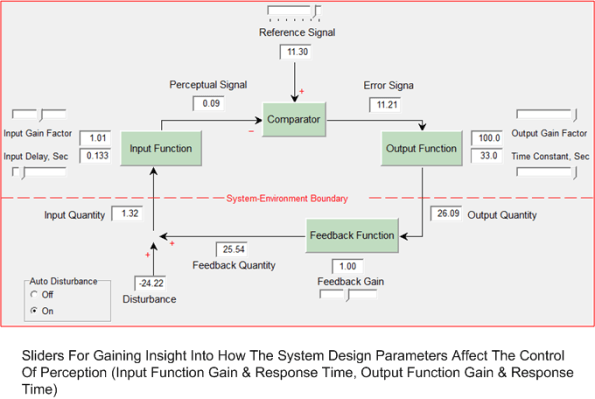

The figure below represents a PCT unit of behavioral organization, the Feedback Control System (FCS). An FCS is a closed loop with not one independent input (e.g. stimulus or command), but two. One input, the reference signal, is sourced from the output function of a higher level control unit(s). The second input, an amalgam of environmental disturbances, “invades” the loop from outside the organism. Both inputs act on the closed loop as a whole and the purpose of the FCS is to continuously act on the environment (via muscular exertion) to maintain the perceptual signal as close to the reference signal as possible. As the reference changes, the behavior changes. As the disturbance changes, the behavior changes. Since action is behavior, the FCS exhibits behavior to control perception; behavior is the control of perception.

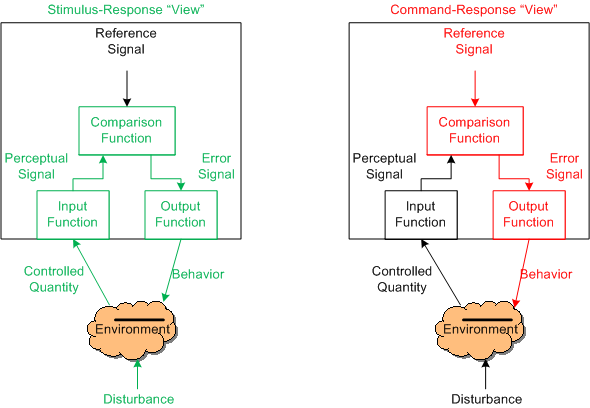

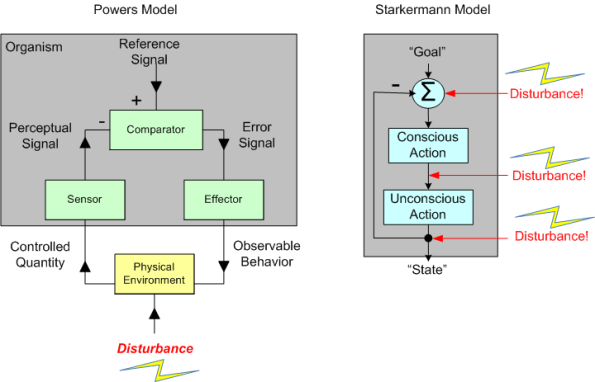

The figure below depicts models of the stimulus-response and command-response views in terms of the PCT FCS. The foremost feature to notice is that there is no loop in either model – it’s broken. The second major difference is that neither model has two inputs.

In the Stimulus-Response model, the linear, causal path of action is: Stimulus (a.k.a Disturbance) ->Organism->Behavior. In the Command-Response model, the linear, causal path of action is: Command (a.k.a Reference)->Organism->Behavior. Hence, the models can be reduced to these simple (and bankrupt) renderings of a dumb-ass organism totally under the control of “something in the external environment“:

So, you may ask: “How could our best and brightest minds in psychology and sociology gotten it so wrong for so long; and why don’t they embrace PCT to learn how living systems really tic?” It’s because they erroneously applied Newton’s linear cause-effect approach for the physics of inanimate objects to living beings and they’ve thoroughly crystallized their UCBs into cement bunkers.

When you push a rock, there is no internal resistance from the rock and Newton’s laws kick into action. When you push a human being, you’ll encounter internal resistance and Newton’s laws don’t apply – control theory applies.

Compounding the difficulty has been a surprising tendency for scientists who are normally careful to know what they are talking about to leap to intuitive conclusions about the properties and capabilities of control systems, without first having become personally acquainted with the existing state of theart. If any criticism is warranted, it is for promulgating statements with an authoritative air without having verified personally that they are justified. – Bill Powers

D’oh! BD00 takes major offense at Bill’s last sentence.

Related articles

- Normal, Slave, Almost Dead, Wimp, Unstable (bulldozer00.com)

- Nine Plus Levels (bulldozer00.com)

- Cross-Disciplinary Pariahs (bulldozer00.com)

- Extrapolation, Abstraction, Modeling (bulldozer00.com)

- Shall And Shall Not (bulldozer00.com)

Message-Centric Vs. Data-Centric

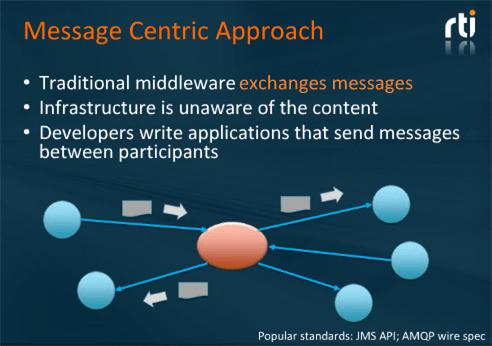

The slide below, plagiarized from a recent webinar presented by RTI Inc’s CEO Stan Schneider, shows the evolution of distributed system middleware over the years.

At first, I couldn’t understand the difference between the message-centric pub-sub (MCPS) and data-centric pub-sub (DCPS) patterns. I thought the difference between them was trivial, superficial, and unimportant. However, as Stan’s webinar unfolded, I sloowly started to “get it“.

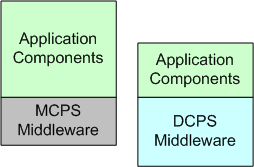

In MCPS, application tier messages are opaque to to the middleware (MW). The separation of concerns between the app and MW tiers is clean and simple:

In DCPS systems, app tier messages are transparent to the MW tier – which blurs the line between the two layers and violates the “ideal” separation of concerns tenet of layered software system design. Because of this difference, the term “message” is superceded in DCPS-based technologies (like the OMG‘s DDS) by the term “topic“. The entity formerly known as a “message” is now defined as a topic sample.

Unlike MCPS MW, DCPS MW supports being “told” by the app tier pub-sub components which Quality Of Service (QoS) parameters are important to each of them. For example, a publisher can “promise” to send topic samples at a minimum rate and/or whether it will use a best-effort UDP-like or reliable TCP-like protocol for transport. On the receive side, a subscriber can tell the MW that it only wants to see every third topic sample and/or only those samples in which certain data-field-filtering criteria are met. DCPS MW technologies like DDS support a rich set of QoS parameters that are usually hard-coded and frozen into MCPS MW – if they’re supported at all.

With smart, QoS-aware DCPS MW, app components tend to be leaner and take less time to develop because the tedious logic that implements the QoS functionality is pushed down into the MW. The app simply specifies these behaviors to the MW during launch and it gets notified by the MW during operation when QoS requirements aren’t being, or can’t be, met.

The cost of switching from an MCPS to a DCPS-based distributed system design approach is the increased upfront, one-time, learning curve (or more likely, the “unlearning” curve).

Related articles

From The Ground Up

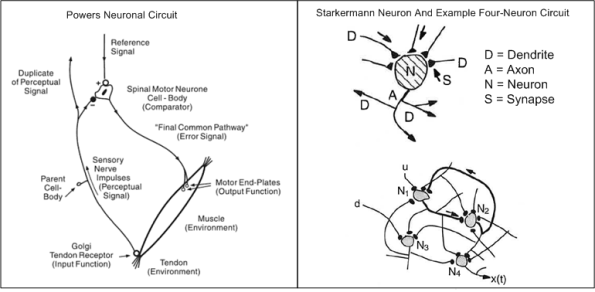

In developing their feedback control system-based models (see below) for exploring the nature of human behavior, both Bill Powers and Rudy Starkermann really did start from the ground up.

By “the ground up“, I mean that their theories started with the basic building blocks of the brain and nervous system. The diagram below shows examples of Powers’s and Starkermann’s underlying neuronal models.

Unlike classical Skinnerian “behaviorists“, whose theories are founded on more abstract, “black box”, empirical findings, BD00 believes that Bill and Rudy’s theories are much more closer to the “truth” (whatever the hell that may be) behind what motivates human behavior. What do you think?

Related articles

- Cross-Disciplinary Pariahs (bulldozer00.com)

- Building The Perfect Beast (bulldozer00.com)

- Nine Plus Levels (bulldozer00.com)

Cross-Disciplinary Pariahs

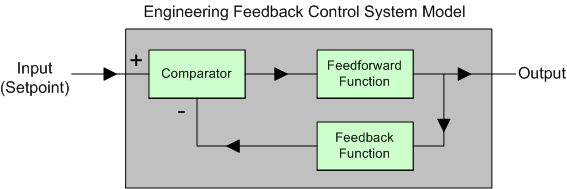

The figure below shows a simplified version of the classic engineering Feedback Control System (FCS). There are two significant features that distinguish an FCS from a typical engineering system. First, the input is not a raw signal to be manipulated in order to produce a derived output of added informational value. It is a “desired” setpoint (or goal, or reference) to be “achieved” by the system’s design.

The second feature is the feedback loop which taps off the output signal and provides real-time evidence to the comparator of how well the output is converging to (or diverging from) the desired setpoint. For a given application, the system’s innards are designed such that the output tracks its input with hi fidelity – even in the presence of “disturbances” (e.g. noise) that infiltrate the system.

In purely technical systems (as opposed to socio-technical systems), the FCS system output would typically be connected to an “actuator” device like a motor, a switch, a valve, a furnace, etc that affects an important measurable quantity in the external environment. The desired setpoints for these type of systems would be motor speed, switch position, valve position, and temperature, respectively. The mathematics of how engineering FCSs behave been known since the 1930s.

In defiance of mainstream psychology and sociology pedagogy, Bill Powers and Rudy Starkermann spent much of their careers applying control theory concepts to their own innovative theories of human behavior. Their heretical, cross-disciplinary approaches to psychology and sociology have kept them oppressed and out of the mainstream much like Deming, Ackoff, Argyris in management “science”.

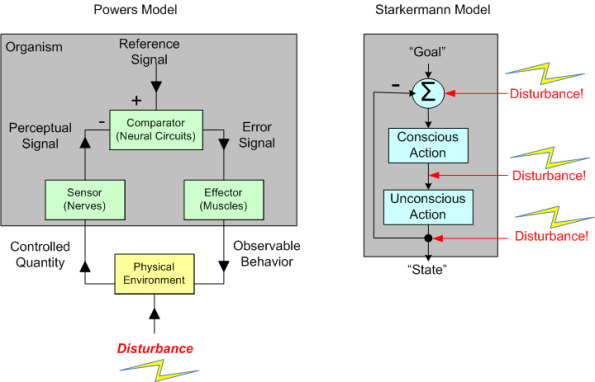

The figure below shows (big simplifications of) the Powers and Starkermann models side by side. Note the similarities between them and also between them and the classic engineering FCS.

- Engineering FCS: Setpoint/Comparator/Feedback Loop

- Powers: Reference/Comparator/Feedback Loop

- Starkermann: Goal/Summing Node/Feedback Loop

The big (and it’s huge) difference between the Starkermann/Powers models and the engineering FCS model is that Starkermann’s goal and Powers’ reference signal originate from within the system whereas the dumb-ass engineering FCS must “be told” what the desired setpoint is by something outside of itself (a human or another mechanistic system designed by a human). In the Starkermann/Powers FCS models of human behavior, “being told” is processed as a disturbance.

If you delve deeper into the “obscure” work of Starkermann and Powers, your world view of the behavior of individuals and groups of individuals just may change – for the better or the worse.

Related articles

- Building The Perfect Beast (bulldozer00.com)

- Normal, Slave, Almost Dead, Wimp, Unstable (bulldozer00.com)

- 1, 2, X, Y (bulldozer00.com)

- The Dispute Over Control Theory (docs.google.com)

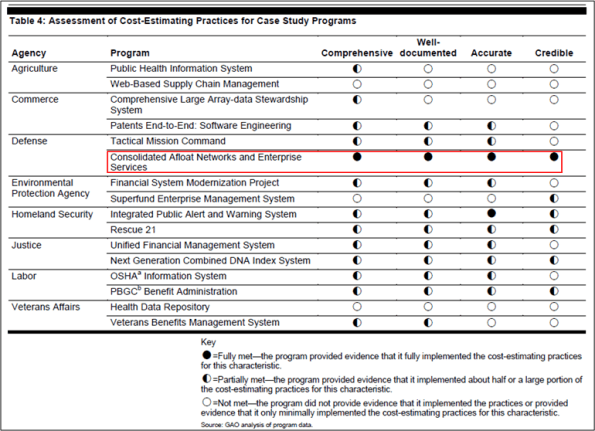

Citizen CANES

On the same day that the US government General Accountability Office (GAO) released its “Software Development: Effective Practices And Federal Challenges In Applying Agile Methods” report, it also released a report titled “INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY COST ESTIMATION: Agencies Need to Address Significant Weaknesses in Policies and Practices“. In this report, the GAO compared cost estimation policies and procedures to best practices at eight agencies. It also reviewed the documentation supporting cost estimates for 16 major investments at those eight agencies—representing about $51.5 billion of the planned IT spending for fiscal year 2012. The table below summarizes the GAO findings.

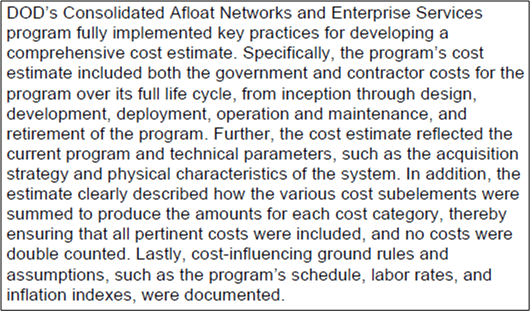

As you can see, only one out of sixteen programs fully met the mighty GAO criteria for “effective” cost estimation: the Navy’s “Consolidated Afloat Networks and Enterprise Services” (CANES) investment. Here’s the GAO’s glowing, bureaucratic-speak assessment of the citizen CANES cost estimation performance as of July 2012:

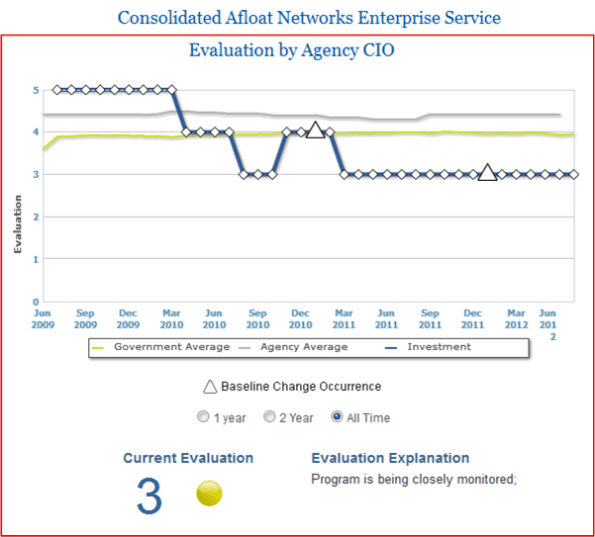

Out of curiosity, I googled the exemplar CANES program. Here’s what I found on the US government’s “IT Dashboard” website:

Note that after debuting with a rating of 5 (Low Risk) in 2009, CANES is currently rated at 3 (medium risk) and is being “closely monitored” by some higher-ups in the infallible chain of command.

Of course, no one, not even that omniscient and omnipresent devil BD00, can tell what will happen to CANES in the future. The point of this post is that spending lots of money and time on meticulous cost estimation to satisfy some authority’s arbitrary and subjective criteria (comprehensive, well-documented, accurate, credible) doesn’t guarantee squat about the future. It does, however, provide a temporary and comfortable illusion of control that “official watchers” crave. We can call it the linus-blanket affect. Maybe coarser and less comprehensive estimation techniques can work just as well or better?

Comprehensiveness is the enemy of comprehensibility – Martin Fowler

Normal, Slave, Almost Dead, Wimp, Unstable

Mr. William T. Powers is the creator (discoverer?) of “Perceptual Control Theory” (PCT). In a nutshell, PCT asserts that “behavior controls perception“. His idea is the exact opposite of the stubborn, entrenched, behaviorist mindset which auto-assumes that “perception controls behavior“.

This (PCT) interpretation of behavior is not like any conventional one. Once understood, it seems to match the phenomena of behavior in an effortless way. Before the match can be seen, however, certain phenomena must be recognized. As is true for all theories, phenomena are shaped by theories as much as theories are shaped by phenomena. – Bill Powers

On the Living Control Systems III web page, you can download software that contains 13 interactive demos of PCT in action:

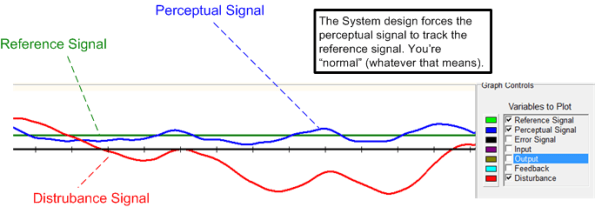

The other day, I spent several hours experimenting with the “LiveBlock” demo in an attempt to understand PCT more deeply. When the demo is launched, the majority of the window is occupied by a fundamental, building-block feedback control system:

When the “Auto-Disturbance” radio option in the lower left corner is clicked to “on“, a multi-signal time trace below the model springs to life:

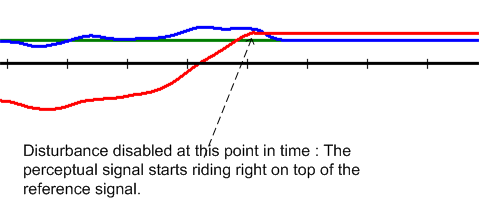

As you can see, while operating under stable, steady-state circumstances, the system does what it was designed to do. It purposefully and continuously changes its “observable” output behavior such that its internal (and thus, externally unobservable) perceptual signal tracks its internal reference signal (also externally unobservable) pretty closely – in spite of being continuously disturbed by “something on the outside“. When the external disturbance is turned off, the real-time trace goes flat; as expected. The perceptual signal starts tracking the reference signal dead nutz on the money such that the difference between it and the reference is negligible:

The Sliders

Turning the disturbance signal “on/off” is not the only thing you can experiment with. When enabled via the control panel to the left of the model (not shown in the clip below), six parameter sliders are displayed:

So, let’s move some of those sliders to see how they affect the system’s operation.

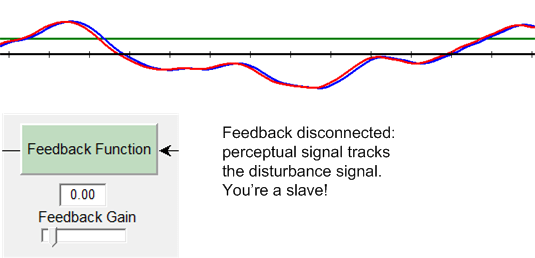

The Slave

First, we’ll break the feedback loop by decreasing the “Feedback Gain” setting to zero:

Almost Dead

Next, let’s disable the input to the system by moving the “Input Gain” slider as far to the left as we can:

The Wimp

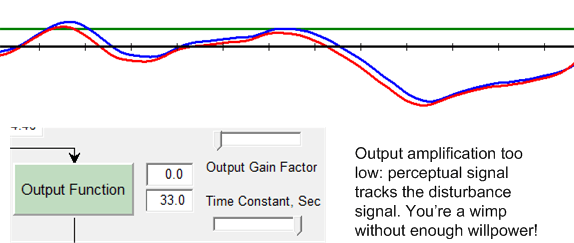

Next, let’s cripple the system’s output behavior by moving the “Output Gain” slider as far to the left as we can:

Let’s Go Unstable!

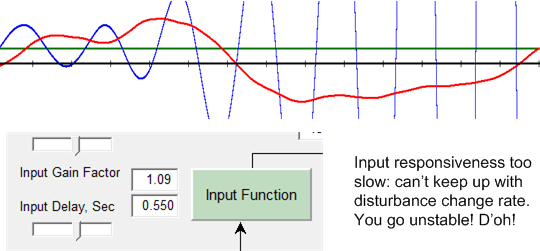

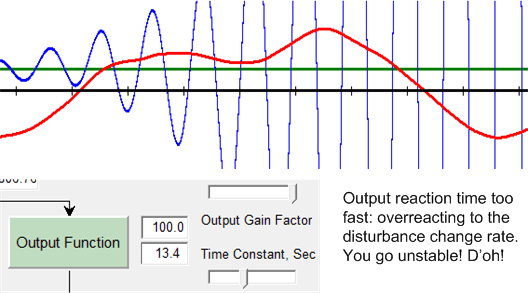

Finally, let’s first move the “Input Delay” slider to the right to decrease the response time and then subsequently move the “Output Time Constant” slider to the left to increase the reaction time:

So, what are you? Normal, a slave, almost dead, a wimp, or an unstable wacko (like BD00)?

I’ve always been pretty much a blue-collar type, by training and by preference. – Bill Powers

Related articles

- Nine Plus Levels (bulldozer00.com)

- Extrapolation, Abstraction, Modeling (bulldozer00.com)

Extrapolation, Abstraction, Modeling

In the beginning of his book, “Behavior: The Control Of Perception“, Bill Powers asserts that there are three ways of formulating a predictive theory of behavior: extrapolation, abstraction, and modeling.

Extrapolation and abstraction are premised on accumulating a collection observations of behaviors and ferreting out recurring patterns applicable under many contexts and input situations. Modeling goes one level deeper and is based on formulating an organizational structure of the internal mechanisms that cause the observed behaviors.

For 30 years prior to the discovery/development/refinement of control theory (and continuing on today because of entrenched mindsets), psychologists and sociologists formulated theories of behavior based on extrapolation and abstraction. Because the human nervous system and brain were (and still are) unfathomably complex, they didn’t even try to model any underlying mechanisms. They treated organisms as dumb-ass, purposeless, “black box” responders to stimuli.

Bill Powers didn’t accept the superficial approaches and black box conclusions of the social “sciences” crowd. He went deeper and turned opaque-black into transparent-white with the relentless modeling and testing of his control system hypothesis of behavior:

Note that in Bill’s model, there is an internal goal that determines the response to a given “disturbance“. Thus, given the same disturbance at two different points in time, the white box model can generate different responses whereas the black box model would always generate the same response.

For example, the white box model explains anomalies like why, on the 100th test run, a mouse won’t press a button to get a food pellet as it did on the 99 previous runs. In this case, the internal goal may be to “eat until satiated“. When the internal goal is achieved, the externally observed behavior changes because the stimulus is no longer important to the mouse.

Theories based on extrapolation and abstraction are useful for predicting short term actions and trends within a certain probability, but when a physical model of the underlying mechanisms of a phenomenon is discovered, it explains a lot of anomalies unaccounted for by extrapolation/abstraction.

For a taste of Mr. Powers’ control system-based theory of behavior, download and experiment with the software provided here: Living Control Systems III.

Espoused Vs. In-Use

Although we say we value openness, honesty, integrity, respect, and caring, we act in ways that undercut these values. For example, rather than being open and honest, we say one thing in public and another in private—and pretend that this is the rational thing to do. We then deny we are doing this and cover up our denial. – Chris Argyris

Guys like Chris Argyris, Russell Ackoff, and W. E. Deming have been virtually ignored over the years by the guild of professional management because of their in your face style. The potentates in the head shed don’t want to hear that they and their hand picked superstars are the main forces holding their borgs in the dark ages while the 2nd law of thermodynamics relentlessly chips away at the cozy environment that envelopes their (not-so) firm.

Chris Argyris’s theory of behavior in an organizational setting is based on two conflicting mental models of action:

- Model I: The objectives of this theory of action are to: (1) be in unilateral control; (2) win and do not lose; (3) suppress negative feelings; and (4) behave rationally.

- Model II: The objectives of this theory of action are to: (1) seek valid (testable) information; (2) create informed choice; and (3) monitor vigilantly to detect and correct error.

The purpose of Model I is to protect and defend the fabricated “self” against fundamental, disruptive change. The patterns of behavior invoked by model I are used by people to protect themselves against threats to their self-esteem and confidence and to protect groups, intergroups, and organizations to which they belong against fundamental, disruptive change. D’oh!

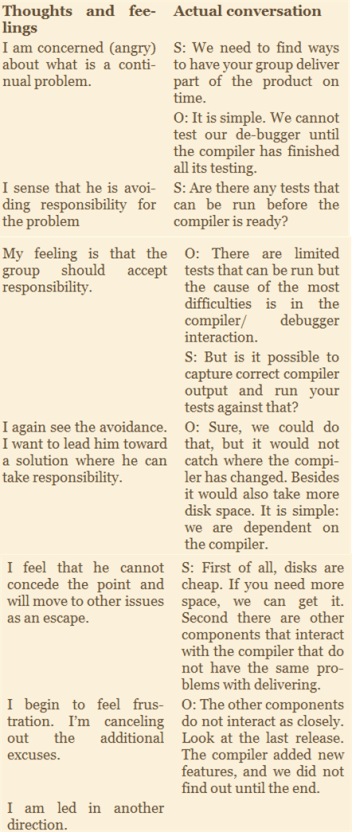

From over 10,000 empirical cases collected over decades of study, Mr. Argyris has discovered that most people (at all levels in an org) espouse Model II guidance while their daily theory in-use is driven by Model I. The tool he uses to expose this espoused vs. in-use model discrepancy is the left-hand-column/right-hand-column method, which goes something like this:

- In a sentence or two identify a problem that you believe is crucial and that you would like to solve in more productive ways than you have hitherto been able to produce.

- Assume that you are free to interact with the individuals involved in the problem in ways that you believe are necessary if progress is to be made. What would you say or do with the individuals involved in ways that you believe would begin to lead to progress. In the right hand column write what you said (or would say if the session is in the future). Write the conversation in the form of a play.

- In the left-hand column write whatever feelings and thoughts you had while you were speaking that you did not express. You do not have to explain why you did not make the feelings and thoughts public.

What follows is an example case titled “Submerging The Primary Issue” from Chris’s book, “Organizational Traps:Leadership, Culture, Organizational Design“. A superior (S) wrote it in regard to his relationship with a subordinate (O) regarding O’s performance.

The primary issue in the superior’s mind, never directly spoken in the dialog, is his perception that the subordinate lacks a sense of responsibility. The issue that *did* end up being discussed was a technical one. (I’d love to see the same case as written by the subordinate. I’d also like to see the case re-written by the superior in a non-supervised environment.)

When Mr. Argyris pointed out the discrepancy between the left and right side themes to the case writer and 1000s of other study participants, they said they didn’t speak their true thoughts out of a concern for others. They did not want to embarrass or make others defensive. Their intention was to show respect and caring.

So, are the reasons given for speaking one way while thinking a different way legitimately altruistic, or are they simply camouflage for the desire to maintain unilateral control and “win“? The evidence Chris Argyris has amassed over the years indicates the latter. But hey, those are traits that lead to the upper echelons in corpoland, no?

Nine Plus Levels

In William T. Powers’ classic and ground-breaking book “Behavior: The Control Of Perception“, Mr. Powers derives a theoretical model of the human nervous system as a stacked, nine-level hierarchical control system that collides with the standard behaviorist stimulus-response model of behavior. As the book title conveys, his ultimate heretical conclusion is that behavior controls perception; not vice-versa.

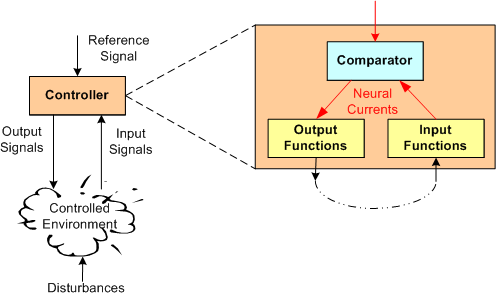

The figure below shows a model of a control system building block. The controller’s job is to minimize the error between a “reference signal” (that originates from “somewhere” outside of the controller) and some feature in the external environment that can be “disturbed” from the status quo by other, unknown forces in the environment.

Notice that the comparator is one level removed from physical reality via the transformational input and output functions. An input function converts a physical effect into a simplified neural current representation and an output function does the opposite. Afterall, everything we sense and every action we perform is ultimately due to neural currents circulating through us and being interpreted as something important to us.

So, what are the nine levels in Mr. Powers’ hierarchy, and what is the controlled quantity modeled by the reference signal at each level? BD00 is glad you asked:

Starting at the bottom level, the controlled variables get more and more abstract as we move upward in the hierarchy. Mr. Powers’ hierarchy ends at 9 levels only because he doesn’t know where to go after “concepts“.

So, who/what provides the “reference signal” at the highest level in the hierarchy? God? What quantity is it intended to control? Self-esteem? Survival? Is there a “top” at all, or does the hierarchy extend on to infinity; driven by evolutionary forces? The ultimate question is “who’s controlling the controller?“.

This post doesn’t come close to serving justice to Mr. Powers’ work. His logical, compelling, and novel derivation of the model from the ground up is fascinating to follow. Of course, I’m a layman but it’s hard to find any holes/faults in his treatise, especially in the lower, more concrete levels of the hierarchy.

Note: Thanks once again to William L. Livingston for steering me toward William T. Powers. His uncanny ability to discover and integrate the work of obscure, “ignored”, intellectual powerhouses like Mr. Powers into his own work is amazing.