Archive

Healthy Debates

The article, “Overconfidence May Be a Result of Social Politeness”, opens up with:

Since society has taught us not to hurt other people’s feelings, we rarely hear the truth about ourselves, even when we really deserve it.

Phew, BD00 is glad this is the case. Otherwise BD00 would be inundated with “negative feedback” for being a baddy. Uh, he actually does get what “he deserves” occasionally, but what da hey.

Florida State University researcher Joyce Ehrlinger, upon whose research the article is based, empirically validated the following hypothesis to some degree:

If person A expressed views to a political subject that person B found contradictory to their own, the result would not be a healthy debate, but just silence from B – and an associated touch of overconfidence from A.

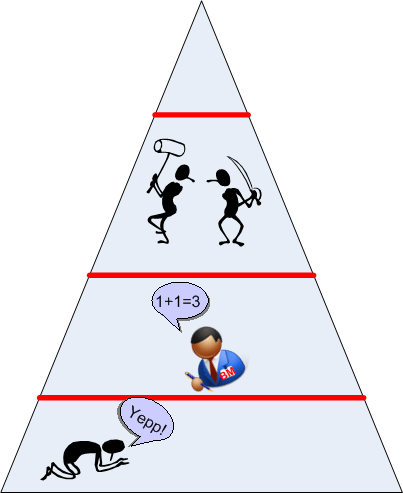

Now, imagine applying this conjecture to a boss-subordinate relationship in a hierarchical command and control bureaucracy. Bureaucratic system design natively discourages healthy debate up and down the chain of command and (almost) everybody complies with this design constraint. As a result, overconfidence increases as one moves up the chain. Healthy debates can, and do, occur among peers at any given level, but up-and-down-the-ladder debates on issues that matter are rare indeed. Hasn’t this been your experience?

Message-Centric Vs. Data-Centric

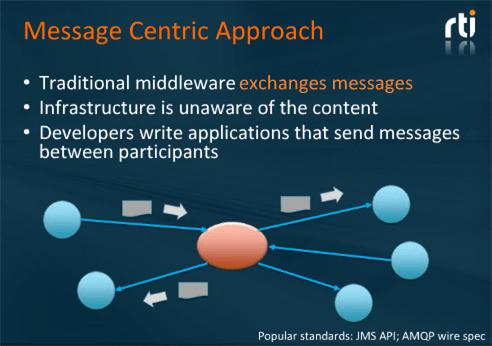

The slide below, plagiarized from a recent webinar presented by RTI Inc’s CEO Stan Schneider, shows the evolution of distributed system middleware over the years.

At first, I couldn’t understand the difference between the message-centric pub-sub (MCPS) and data-centric pub-sub (DCPS) patterns. I thought the difference between them was trivial, superficial, and unimportant. However, as Stan’s webinar unfolded, I sloowly started to “get it“.

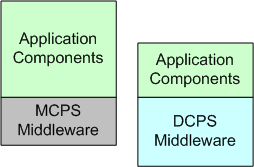

In MCPS, application tier messages are opaque to to the middleware (MW). The separation of concerns between the app and MW tiers is clean and simple:

In DCPS systems, app tier messages are transparent to the MW tier – which blurs the line between the two layers and violates the “ideal” separation of concerns tenet of layered software system design. Because of this difference, the term “message” is superceded in DCPS-based technologies (like the OMG‘s DDS) by the term “topic“. The entity formerly known as a “message” is now defined as a topic sample.

Unlike MCPS MW, DCPS MW supports being “told” by the app tier pub-sub components which Quality Of Service (QoS) parameters are important to each of them. For example, a publisher can “promise” to send topic samples at a minimum rate and/or whether it will use a best-effort UDP-like or reliable TCP-like protocol for transport. On the receive side, a subscriber can tell the MW that it only wants to see every third topic sample and/or only those samples in which certain data-field-filtering criteria are met. DCPS MW technologies like DDS support a rich set of QoS parameters that are usually hard-coded and frozen into MCPS MW – if they’re supported at all.

With smart, QoS-aware DCPS MW, app components tend to be leaner and take less time to develop because the tedious logic that implements the QoS functionality is pushed down into the MW. The app simply specifies these behaviors to the MW during launch and it gets notified by the MW during operation when QoS requirements aren’t being, or can’t be, met.

The cost of switching from an MCPS to a DCPS-based distributed system design approach is the increased upfront, one-time, learning curve (or more likely, the “unlearning” curve).

Related articles

Cross-Disciplinary Pariahs

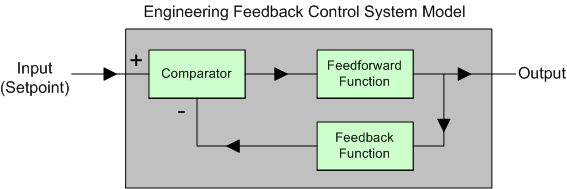

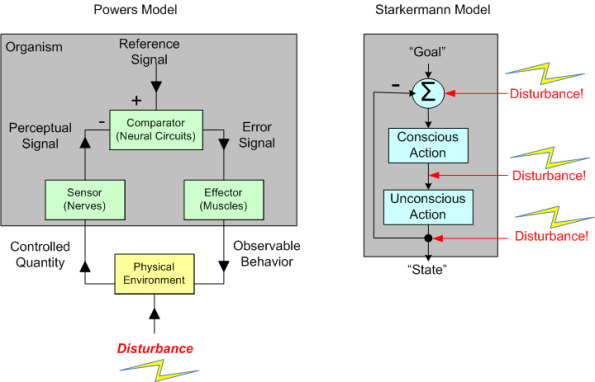

The figure below shows a simplified version of the classic engineering Feedback Control System (FCS). There are two significant features that distinguish an FCS from a typical engineering system. First, the input is not a raw signal to be manipulated in order to produce a derived output of added informational value. It is a “desired” setpoint (or goal, or reference) to be “achieved” by the system’s design.

The second feature is the feedback loop which taps off the output signal and provides real-time evidence to the comparator of how well the output is converging to (or diverging from) the desired setpoint. For a given application, the system’s innards are designed such that the output tracks its input with hi fidelity – even in the presence of “disturbances” (e.g. noise) that infiltrate the system.

In purely technical systems (as opposed to socio-technical systems), the FCS system output would typically be connected to an “actuator” device like a motor, a switch, a valve, a furnace, etc that affects an important measurable quantity in the external environment. The desired setpoints for these type of systems would be motor speed, switch position, valve position, and temperature, respectively. The mathematics of how engineering FCSs behave been known since the 1930s.

In defiance of mainstream psychology and sociology pedagogy, Bill Powers and Rudy Starkermann spent much of their careers applying control theory concepts to their own innovative theories of human behavior. Their heretical, cross-disciplinary approaches to psychology and sociology have kept them oppressed and out of the mainstream much like Deming, Ackoff, Argyris in management “science”.

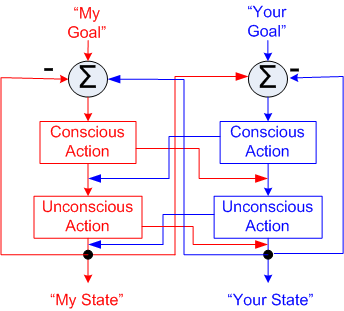

The figure below shows (big simplifications of) the Powers and Starkermann models side by side. Note the similarities between them and also between them and the classic engineering FCS.

- Engineering FCS: Setpoint/Comparator/Feedback Loop

- Powers: Reference/Comparator/Feedback Loop

- Starkermann: Goal/Summing Node/Feedback Loop

The big (and it’s huge) difference between the Starkermann/Powers models and the engineering FCS model is that Starkermann’s goal and Powers’ reference signal originate from within the system whereas the dumb-ass engineering FCS must “be told” what the desired setpoint is by something outside of itself (a human or another mechanistic system designed by a human). In the Starkermann/Powers FCS models of human behavior, “being told” is processed as a disturbance.

If you delve deeper into the “obscure” work of Starkermann and Powers, your world view of the behavior of individuals and groups of individuals just may change – for the better or the worse.

Related articles

- Building The Perfect Beast (bulldozer00.com)

- Normal, Slave, Almost Dead, Wimp, Unstable (bulldozer00.com)

- 1, 2, X, Y (bulldozer00.com)

- The Dispute Over Control Theory (docs.google.com)

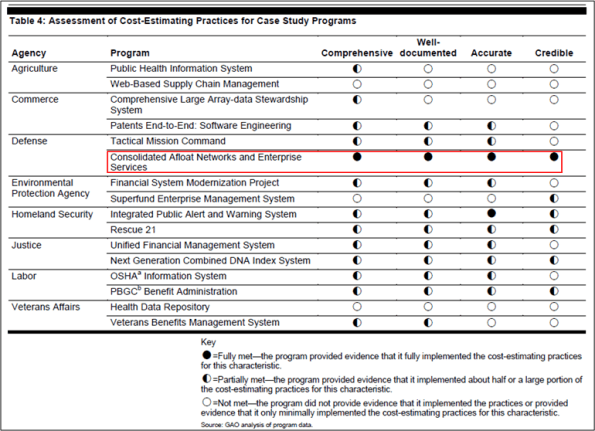

Citizen CANES

On the same day that the US government General Accountability Office (GAO) released its “Software Development: Effective Practices And Federal Challenges In Applying Agile Methods” report, it also released a report titled “INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY COST ESTIMATION: Agencies Need to Address Significant Weaknesses in Policies and Practices“. In this report, the GAO compared cost estimation policies and procedures to best practices at eight agencies. It also reviewed the documentation supporting cost estimates for 16 major investments at those eight agencies—representing about $51.5 billion of the planned IT spending for fiscal year 2012. The table below summarizes the GAO findings.

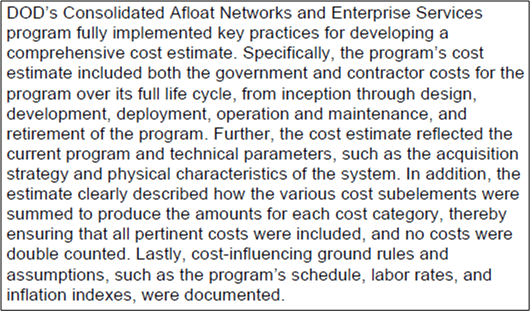

As you can see, only one out of sixteen programs fully met the mighty GAO criteria for “effective” cost estimation: the Navy’s “Consolidated Afloat Networks and Enterprise Services” (CANES) investment. Here’s the GAO’s glowing, bureaucratic-speak assessment of the citizen CANES cost estimation performance as of July 2012:

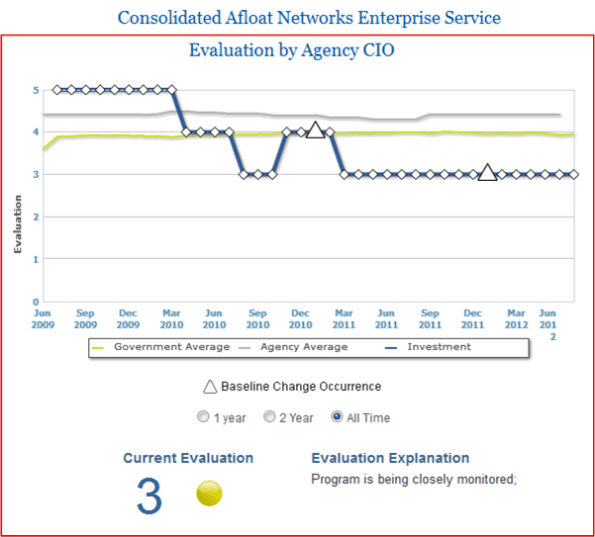

Out of curiosity, I googled the exemplar CANES program. Here’s what I found on the US government’s “IT Dashboard” website:

Note that after debuting with a rating of 5 (Low Risk) in 2009, CANES is currently rated at 3 (medium risk) and is being “closely monitored” by some higher-ups in the infallible chain of command.

Of course, no one, not even that omniscient and omnipresent devil BD00, can tell what will happen to CANES in the future. The point of this post is that spending lots of money and time on meticulous cost estimation to satisfy some authority’s arbitrary and subjective criteria (comprehensive, well-documented, accurate, credible) doesn’t guarantee squat about the future. It does, however, provide a temporary and comfortable illusion of control that “official watchers” crave. We can call it the linus-blanket affect. Maybe coarser and less comprehensive estimation techniques can work just as well or better?

Comprehensiveness is the enemy of comprehensibility – Martin Fowler

1, 2, X, Y

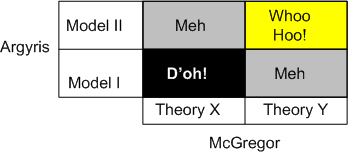

Chris Argyris has his Model 1 and Model 2 theories of action:

- Model I: The objectives of this theory of action are to: (1) be in unilateral control; (2) win and do not lose; (3) suppress negative feelings; and (4) behave rationally.

- Model II: The objectives of this theory of action are to: (1) seek valid (testable) information; (2) create informed choice; and (3) monitor vigilantly to detect and correct error.

Douglas McGregor has his X and Y theories of motivation:

- Theory X: Employees are inherently lazy and will avoid work if they can and that they inherently dislike work.

- Theory Y: Employees may be ambitious and self-motivated and exercise self-control; they enjoy their mental and physical work duties.

Let’s do an Argyris-McGregor mashup and see what types of enterprises emerge:

Snapback To “Business As Usual”

Over the years, I’ve read quite a few terrific and insightful reports from the General Accountability Office (GAO) on the state of several big, software-intensive, government programs. The GAO is the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of the US Congress. Its mission is to:

help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. The GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions.

In a newly released report titled “Software Development: Effective Practices And Federal Challenges In Applying Agile Methods“, the GAO communicated the results of a study it performed on the success of using “agile” software methods in five agencies (a.k.a. bureaucracies): the Department of Commerce, Defense, Veterans Affairs, the Internal Revenue Service, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

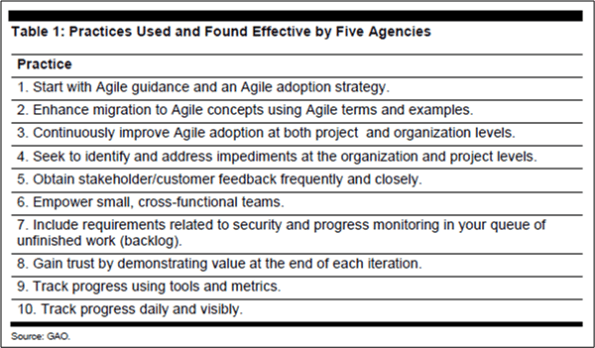

The GAO report deems these 10 best practices as effective for taking an agile approach:

Yawn. Every time I read a high-falutin’ list like this, I’m hauntingly reminded of what Chris Argyris essentially says:

Most advice given by “gurus” today is so abstract as to be un-actionable.

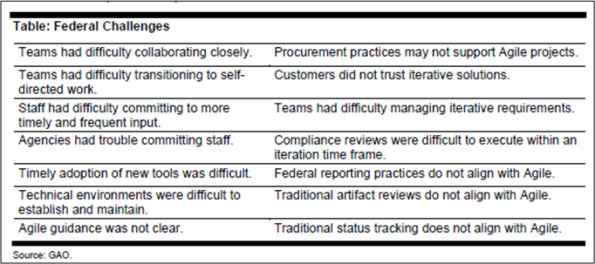

The GAO report also found more than a dozen challenges with the agile approach for federal agencies:

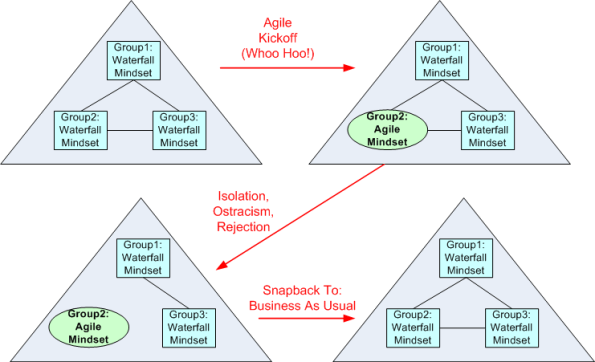

Again, yawn. These are not only federal challenges…. they’re HUGE commercial challenges as well. When the whole borg infrastructure, its policies, its protocols, its (planning, execution, reporting) procedures, and most importantly, its sub-group mindsets are steadfastly waterfall-dominated, here’s what usually happens when “agile” is attempted by a courageous borg sub-group:

D’oh! I hate when that happens.

Building The Perfect Beast

The figure below illustrates a simplified model of a Starkermann dualism. My behavior can contribute to (amity), or detract from (enmity) your well being and vice versa.

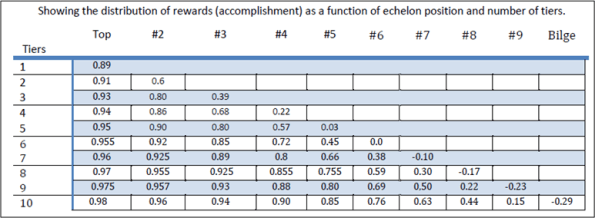

Mr. Starkermann spent decades developing and running simulations of his models to gain an understanding of the behavior of groups. The table below (plucked from Bill Livingston’s D4P4D) shows the results of one of those simulation runs.

The table shows the deleterious effects of institutional hierarchy building. In a single tier organization, the group at the top, which includes everyone since no one is above or below anybody else, attains high levels of achievement (89%). In a 10 layer monstrosity, those at the top benefit greatly (98% achievement) at the expense of those dwelling at the bottom – who actually gain nothing and suffer the negative consequences of being a member of the borg.

What do you think? Does this model correspond to reality? How many tiers are in your org and where are you located?

Normal, Slave, Almost Dead, Wimp, Unstable

Mr. William T. Powers is the creator (discoverer?) of “Perceptual Control Theory” (PCT). In a nutshell, PCT asserts that “behavior controls perception“. His idea is the exact opposite of the stubborn, entrenched, behaviorist mindset which auto-assumes that “perception controls behavior“.

This (PCT) interpretation of behavior is not like any conventional one. Once understood, it seems to match the phenomena of behavior in an effortless way. Before the match can be seen, however, certain phenomena must be recognized. As is true for all theories, phenomena are shaped by theories as much as theories are shaped by phenomena. – Bill Powers

On the Living Control Systems III web page, you can download software that contains 13 interactive demos of PCT in action:

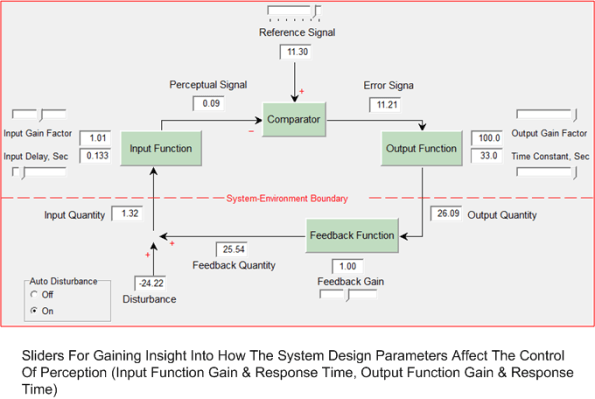

The other day, I spent several hours experimenting with the “LiveBlock” demo in an attempt to understand PCT more deeply. When the demo is launched, the majority of the window is occupied by a fundamental, building-block feedback control system:

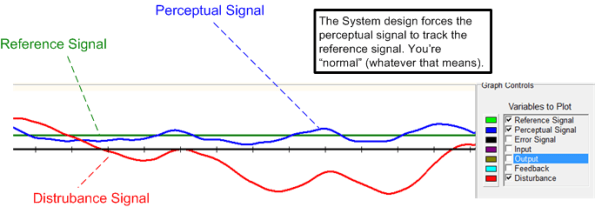

When the “Auto-Disturbance” radio option in the lower left corner is clicked to “on“, a multi-signal time trace below the model springs to life:

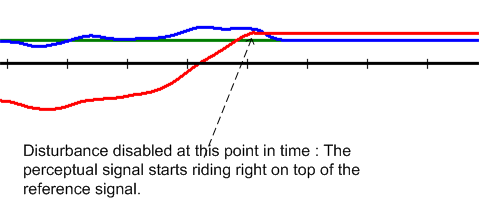

As you can see, while operating under stable, steady-state circumstances, the system does what it was designed to do. It purposefully and continuously changes its “observable” output behavior such that its internal (and thus, externally unobservable) perceptual signal tracks its internal reference signal (also externally unobservable) pretty closely – in spite of being continuously disturbed by “something on the outside“. When the external disturbance is turned off, the real-time trace goes flat; as expected. The perceptual signal starts tracking the reference signal dead nutz on the money such that the difference between it and the reference is negligible:

The Sliders

Turning the disturbance signal “on/off” is not the only thing you can experiment with. When enabled via the control panel to the left of the model (not shown in the clip below), six parameter sliders are displayed:

So, let’s move some of those sliders to see how they affect the system’s operation.

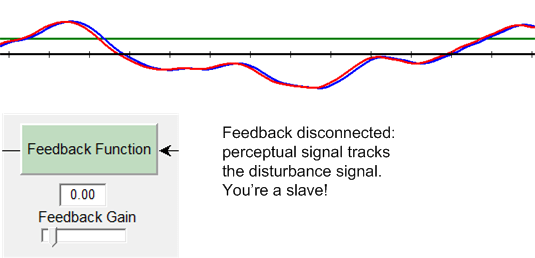

The Slave

First, we’ll break the feedback loop by decreasing the “Feedback Gain” setting to zero:

Almost Dead

Next, let’s disable the input to the system by moving the “Input Gain” slider as far to the left as we can:

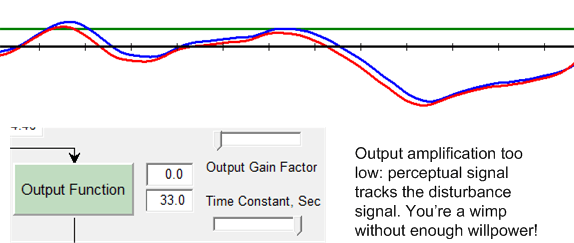

The Wimp

Next, let’s cripple the system’s output behavior by moving the “Output Gain” slider as far to the left as we can:

Let’s Go Unstable!

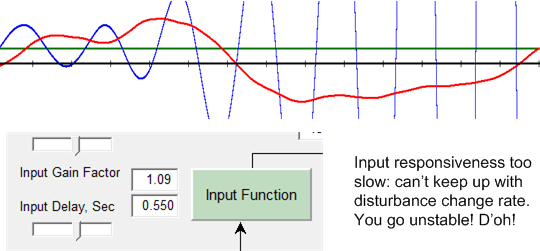

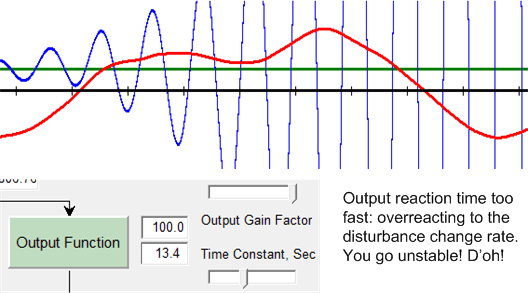

Finally, let’s first move the “Input Delay” slider to the right to decrease the response time and then subsequently move the “Output Time Constant” slider to the left to increase the reaction time:

So, what are you? Normal, a slave, almost dead, a wimp, or an unstable wacko (like BD00)?

I’ve always been pretty much a blue-collar type, by training and by preference. – Bill Powers

Related articles

- Nine Plus Levels (bulldozer00.com)

- Extrapolation, Abstraction, Modeling (bulldozer00.com)

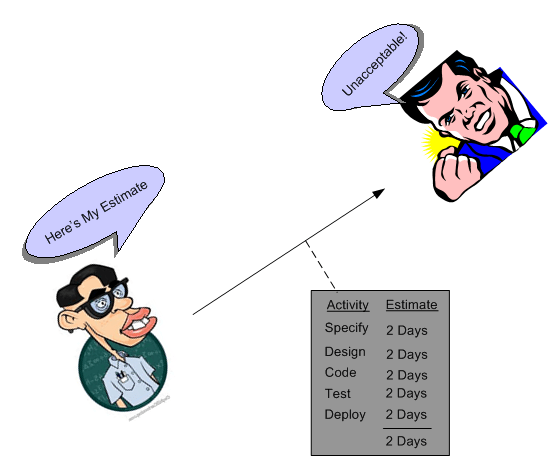

OMITTED ACTIVITIES!

The best book I’ve read (so far) on software estimation is Steve McConnell’s “Software Estimation: Demystifying the Black Art“. Steve is one of the most pragmatic technical authors I know. His whole portfolio of books is worth delving into.

Prior to describing many practical and “doable” estimation practices, Steve presents a dauntingly depressive list of estimation error sources:

- Unstable requirements

- Unfounded optimism

- Subjectivity and bias

- Unfamiliar application domain area

- Unfamiliar technology area

- Incorrect conversion from estimated time to project time (for example, assuming the project team will focus on the project eight hours per day, five days per week)

- Misunderstanding of statistical concepts (especially adding together a set of “best case” estimates or a set of “worst case” estimates)

- Budgeting processes that undermine effective estimation (especially those that require final budget approval in the wide part of the Cone of Uncertainty)

- Having an accurate size estimate, but introducing errors when converting the size estimate to an effort estimate

- Having accurate size and effort estimates, but introducing errors when converting those to a schedule estimate

- Overstated savings from new development tools or methods

- Simplification of the estimate as it’s reported up layers of management, fed into the budgeting process, and so on

- OMITTED ACTIVITIES!

But wait! We’re not done. That last screaming bullet, OMITTED ACTIVITIES!, needs some elaboration:

- Glue code needed to use third-party or open-source software

- Ramp-up time for new team members

- Mentoring of new team members

- Management coordination/manager meetings

- Requirements clarifications

- Maintaining the scripts required to run the daily build

- Participation in technical reviews

- Integration work

- Processing change requests

- Attendance at change-control/triage meetings

- Maintenance work on previous systems during the project

- Performance tuning

- Administrative work related to defect tracking

- Learning new development tools

- Answering questions from testers

- Input to user documentation and review of user documentation

- Review of technical documentation

- Reviewing plans, estimates, architecture, detailed designs, stage plans, code, test cases

- Vacations

- Company meetings

- Holidays

- Sick days

- Weekends

- Troubleshooting hardware and software problems

It’s no freakin’ wonder that the vast majority of software-intensive projects are underestimated, no? To add insult to injury, the unspoken pressure from the “upper layers” to underestimate the activities that ARE actually included in a project plan seals the deal for “perceived” future failure, no? It’s also no wonder that after a few years, good technical people who feel that hands-on creative work is their true calling start agonizing over whether to get the hell out of such a failure-inducing system and make the move on up into the world of politics, one-upsmanship, feigned collaboration, dubious accomplishment, and strategic self-censorship. Bummer for those people and the orgs they dwell in. Bummer for “the whole“.

Killers Or Motivators?

It’s ironic that many of the words and phrases in “100 words that kill your proposal” are used by management and public relations spin doctors to project a false illusion of infallibility:

- Uniquely qualified, very unique, ensure, guarantee

- Premier, world-class, world-renowned, well-seasoned managers

- Leading company, leading edge, leading provider, industry leader, pioneers, cutting edge

- Committed, quality focused, dedicated, trustworthy, customer-first

How can these subjective and tacky words sink a business proposal on the one hand, but (supposedly) inspire and motivate on the other hand?