Archive

The Point Of No Return

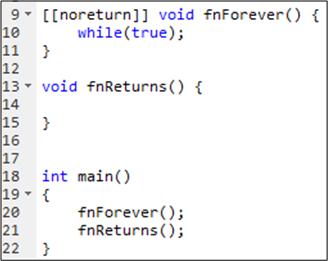

As part of learning the new feature set in C++11, I stumbled upon the weird syntax for the new “attribute” feature: [[ ]]. One of these new C++11 attributes is [[noreturn]].

The [[noreturn]] attribute tells the compiler that the function you are writing will not return control of execution back to its caller – ever. For example, this function will generate a compiler warning or error because even though it returns no value, it does return execution control back to its caller:

The following functions, however, will compile cleanly:

Using [[noreturn]] enables compiler writers to perform optimizations that would otherwise not be available without the attribute. For example, it can silently (but correctly) eliminate the unreachable call to fnReturns() in this snippet:

Note: I used the Coliru interactive online C++ IDE to experiment with the [[noreturn]] attribute. It’s perfect for running quick and dirty learning experiments like this.

The Importance Of Locality

Since I love the programming language he created and I’m a fan of his personal philosophy, I’m always on the lookout for interviews of Bjarne Stroustrup. As far as I can tell, the most recent one is captured here: “An Interview with Bjarne Stroustrup | | InformIT“. Of course, since the new C++11 version of his classic TC++PL book is now available, the interview focuses on the major benefits of the new set of C++11 language features.

For your viewing pleasure and retention in my archives, I’ve clipped some juicy tidbits from the interview and placed them here:

Adding move semantics is a game changer for resource (memory, locks, file handles, threads, and sockets) management. It completes what was started with constructor/destructor pairs. The importance of move semantics is that we can basically eliminate complicated and error-prone explicit use of pointers and new/delete in most code.

TC++PL4 is not simply a list of features. I try hard to show how to use the new features in combination. C++11 is a synthesis that supports more elegant and efficient programming styles.

I do not consider it the job of a programming language to be “secure.” Security is a systems property and a language that is – among other things – a systems programming language cannot provide that by itself.

The repeated failures of languages that did promise security (e.g. Java), demonstrates that C++’s more modest promises are reasonable. Trying to address security problems by having every programmer in every language insert the right run-times checks in the code is expensive and doomed to failure.

Basically, C is not the best subset of C++ to learn first. The “C first” approach forces students to focus on workarounds to compensate for weaknesses and a basic level of language that is too low for much programming.

Every powerful new feature will be overused until programmers settle on a set of effective techniques and find which uses impede maintenance and performance.

I consider Garbage Collection (GC) the last alternative after cleaner, more general, and better localized alternatives to resource management have been exhausted. GC is fundamentally a global memory management scheme. Clever implementations can compensate, but some of us remember too well when 63 processors of a top-end machine were idle when 1 processor cleaned up the garbage for them all. With clusters, multi-cores, NUMA memories, and multi-level caches, systems are getting more distributed and locality is more important than ever.

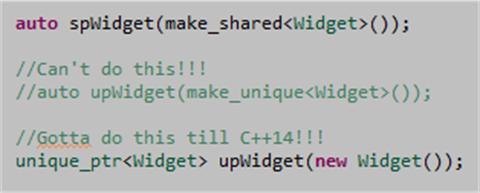

make_unique

On my current project, we’re joyfully using C++11 to write our computationally-dense target processing software. We’ve found that std::shared_ptr and std::unique_ptr are extremely useful classes for avoiding dreaded memory leaks. However, I find it mildly irritating that there is no std::make_unique to complement std::make_shared. It’s great that std::make_unique will be included in the C++14 standard, but whenever we use a std::unique_ptr we gotta include a fugly “new” in our C++11 code until then:

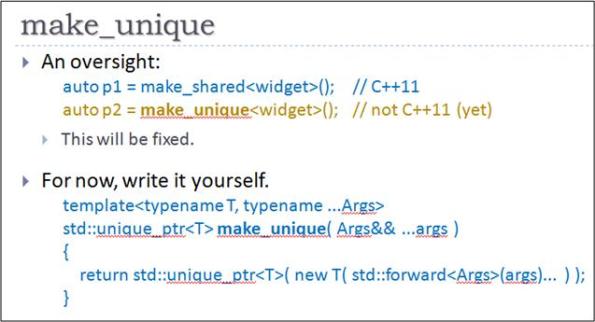

But wait! I stumbled across this helpful Herb Sutter slide:

A variadic function template that uses perfect forwarding. It’s outta my league, but….. Whoo Hoo! I’m gonna add this sucker to our platform library and start using it ASAP.

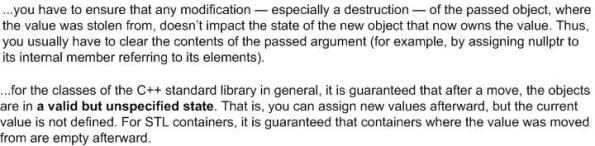

My C++11 “Move” Notes

Being a slow learner, BD00 finds it easier to learn a new topic by researching the writings from multiple sources of authority. BD00 then integrates his findings into his bug-riddled brain as “the truth as he sees it” (not the absolute truth – which is unknowable). The different viewpoints offered up by several experts on a subject tend to fill in holes of understanding that would otherwise go unaddressed. Thus, since BD00 wanted to learn more about how C++11’s new “move” and “rvalue reference” features work, he gathered several snippets on the subject and hoisted them here.

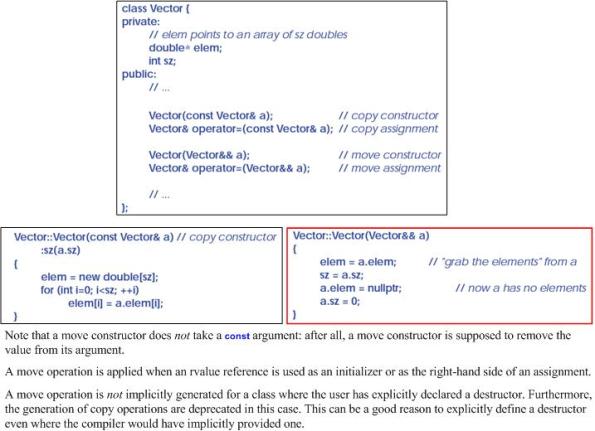

Why Move?

The motivation for adding “rvalue” references and “move” semantics to C++11 to complement its native “copy” semantics was to dramatically improve performance when large amounts of heap-based data need to be transferred from one class object to another AND it is known that preserving the “from” class object’s data is unnecessary (e.g. returning a non-static local object from a function). Rather than laboriously copying each of a million objects from one object to another, one can now simply “move” them.

Unlike its state after a “copy“, a moved-from object’s data is no longer present for further use downstream in the program. It’s like when I give you my phone. I don’t make a copy of it and hand it over to you. After I “move” it to you, I’m sh*t outta luck if I want to call my shrink – until I get a new phone.

Chapter 13 – C++ Primary, Fifth Edition, Lippman, Lajoie, Moo

Chapter 3 – The C++ Programming Language, 4th Edition, Bjarne Stroustrup

Chapter 3 – The C++ Standard Library, 2nd Edition, Nicolai M. Josuttis

Overview Of The New C++ (C++11), Scott Meyers

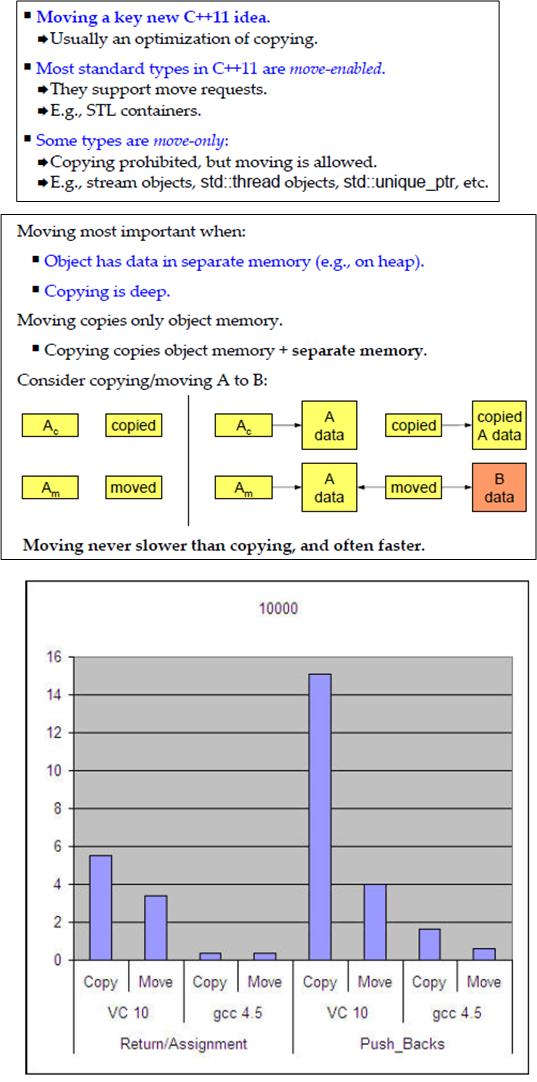

Hyped And Valueless

In “Major Software Development Trends for 2013”, the editors of InfoQ asked its readers to rank several software development trends in terms of their “adoption readiness” and the “value proposition” they offer. As you can see below, the 623 voters (so far) think that “the resurgence of C++” is the least valuable and least adoptable among the 16 listed trends.

My take, and I fully admit to being totally biased for C++11, is that the vast majority of voters are web, mobile, or IT business application developers. They don’t develop real-time and/or safety-critical systems where C and C++ excel. Hell, just looking at the list of trends, you can tell that they are all geared toward web/mobile/IT applications. But that makes sense because the market for those types of apps dwarfs all others and that’s what’s driving the relentless innovation that keeps the software industry fresh, new, and brutally exciting.

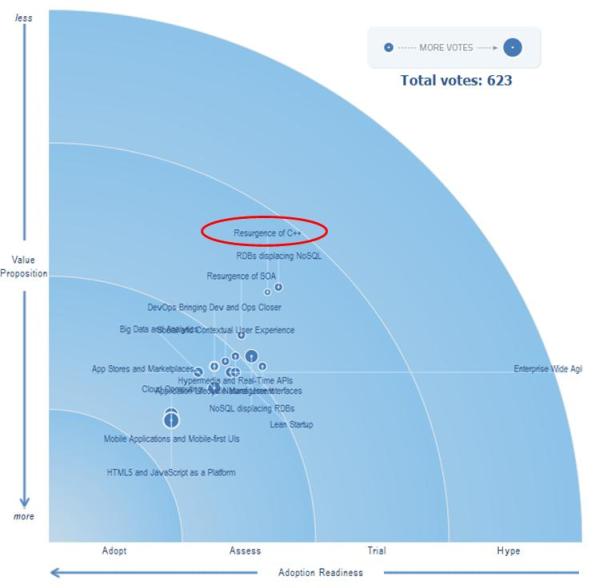

Milliseconds Since The Epoch 2

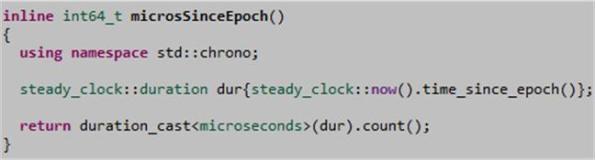

Over a year ago, I hoisted some C++ code on the “Milliseconds Since The Epoch” post for those who were looking for a way to generate timestamps for message tagging and/or event logging and/or code performance measurements. That code was based on the Boost.Date_Time library. However, with the addition of the <chrono> library to C++11, the code to generate millisecond (or microsecond or nanosecond) precision timestamps is not only simpler, it’s now standard:

Here’s how it works:

- steady_clock::now() returns a timepoint object relative to the epoch of the steady_clock (which may or may not be the same as the Unix epoch of 1/1/1970).

- steady_clock::timepoint::time_since_epoch() returns a steady_clock::duration object that contains the number of tick-counts that have elapsed between the epoch and the occurrence of the “now” timepoint.

- The duration_cast<T> function template converts the steady_clock::duration tick-counts from whatever internal time units they represent (e.g. seconds, microseconds, nanoseconds, etc) into time units of milliseconds. The millisecond count is then retrieved and returned to the caller via the duration::count() function.

I concocted this code from the excellent tutorial on clocks/timepoints/durations in Nicolai Josuttis’s “The Standard C++ Library (2nd Edition)“. Specifically, “5.7. Clocks and Timers“.

The C++11 standard library provides three clocks:

- system_clock

- high_resolution_clock

- steady_clock

I used the steady_clock in the code because it’s the only clock that’s guaranteed to never be “adjusted” by some external system action (user change, NTP update). Thus, the timepoints obtained from it via the now() member function never decrease as real-time marches forward.

Note: If you need microsecond resolution timestamps, here’s the equivalent code:

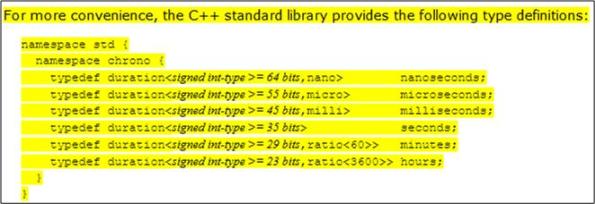

So, what about “rollover“, you ask. As the highlight below from Nicolai’s book shows, the number of bits required by C++11 library implementers increases with increased resolution. Assuming each clock ticks along relative to the Unix epoch time, rollover won’t occur for a very, very, very, very long time; no matter which resolution you use.

Of course, the “real” resolution you actually get depends on the underlying hardware of your platform. Nicolai provides source code to discover what these real, platform-specific resolutions and epochs are for each of the three C++11 clock types. Buy the book if you want to build and run that code on your hardware.

Uniform Initialization Failure?

On our latest distributed system project, we’ve decided to use some of the C++11 features provided by GCC 4.7. Right off the bat, I happily started using the “uniform initialization” feature, the auto keyword, range-for loops, and in-class member initializers.

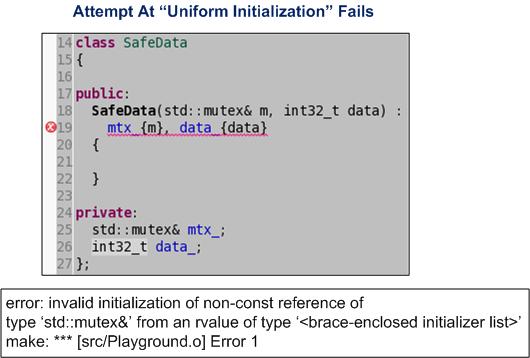

While incorporating uniform initialization all over my crappy code, I either stumbled into a compiler bug or a flaw in my understanding of the feature. I don’t know which is the case, and that’s why I’m gonna ask for your help figuring it out in this “normal” blog post.

Behold the code that the compiler explodes on:

But Mr. Compiler, I’m trying to initialize a non-const reference (std::mutex& mtx_) lvalue with an rvalue of the exact same same type, another non-const reference (std::mutex& m). WTF?

Next, observe the change I had to make to satisfy the almighty compiler:

I’m bummed that I had to destroy the “elegance” (LOL!) of the product code by replacing the C++11 brace pair with the old style parenthesis pair of C++03.

Since little things like this tend to consume me, I explored the annoyance further by writing some little side test programs. I found that the compiler seems to barf every time I try to initialize any reference type via a brace pair – so the problem is not std::mutex specific.

So, I’m asking for your help. Is it a compiler bug, or a misunderstanding on my part?

Update A (12/1/12)

I’ve come to the conclusion that the issue is indeed a compiler bug. While searching for the cause, I found the following paper and set of initializer list examples on Bjarne Stroustrup‘s web site:

According to the man himself, my exploding code should compile cleanly, no?

Update B (12/1/12)

After further research, I’ve flip-flopped. Now I don’t think it’s a problem with the compiler. It’s simply that the std::mutex class is not designed to support an initializer list (of one)? In order to support uniform initialization, I think a class must be explicitly designed to provide it via some sort of constructor syntax that I haven’t learned yet. Thus, unless all the classes used in a program explicitly provide initializer list support, the program must use “mixed initialization” in order to compile. If this is true, then bummer. Uniform initialization doesn’t come “for free” with C++11 – which is what I erroneously thought.

Update C 12/5/12

After yet more research and coding on this annoying issue, I discovered that whether or not brace style initialization works for references is indeed type specific. As the example below shows, brace style initialization compiles fine for a reference to a plain old int.

In the process of experimenting, I also discovered what I think is a g++ 4.7.2 compiler bug:

Note that in this case, I’m trying to brace-init a member of type Base, not a reference to Base. There’s something screwy going on with brace initialization that I don’t understand. Got any advice/insight to share?

A Glimpse Into C++11PL4

At Microsoft’s Build 2012 conference, ISO C++ chairman Herb Sutter introduced the new isocpp.org web site. On the site, you can download a draft version of Chapter 2 from Bjarne Stroustrup‘s upcoming “The C++ Programming Language, 4th Edition“. As I read the chapter and took “the tour“, I noted the new C++11 features that Bjarne used in his graceful narrative. Here they are:

auto, intializer lists, range-for loops, constexpr, enum class, nullptr, static_assert.

Since I’m a big Stroustrup and C++ fan, I just wanted to pass along this tidbit of info to the C++ programmers that happen to stumble upon this blog.

Patience Grasshoppa, Patience

It won’t arrive for awhile, but it’s on its way: the C++11 rendition of Bjarne Stroustrup‘s “The C++ Programming Language“.

In case you didn’t already know, the C++11 editions of these tomes are already available for your consumption:

But of course, you did already did know this. There are gifted copies of each of these references on your and your colleague’s desks because your company cares about you, your productivity growth, and continuously enhancing the quality of its revenue-generating product portfolio. That’s why it obsesses over little, but simultaneously huge, things like this for you, its products, and its future well being. It’s a quiet, low-key, low-cost, win-win-win situation that makes you feel warm and fuzzy each day you walk in the door to joyfully add your contribution to the whole.

And puh-leeze, no comments from the hip and cool Ruby, Python, Java, Go, Scala, C#, etc, peanut galleries. On this bogus blawg, only pope BD00 is approved to promote or trash other programming languages, ideas, groups, concepts, institutions, traditions. Well, you get the idea.

Note: I created the above image at says-it.com. It’s a wonderful site, so hop on over there and give it a whirl.