Archive

CC++

For a comical moment, imagine that the C++ programming language was monopolized by a fortune 500 corpricracy and renamed as CorpoC++. Here’s a list of possible SCOL titles that could be conjured up and bestowed on some lucky people in the CC++ business unit:

- VP Of Exception Handling

- VP of STL containers

- VP of STL algorithms

- VP of Static Polymorphism

- VP of Overloading

- VP of Classes, Structs, and Enums

- VP of Primitive Types

- VP of Dynamic Polymorphism

- VP of Idioms

- VP of Deprecated Features

- VP of Backward C Compatibility

- VP of Syntax

- VP of Reserved Keywords

- VP of Construction, Destruction, and Copy Operations

- VP of Boost Feature Adoption

If you think “design by standards committee” is bad, what kind of monstrosity do you think this merry band of anti-collaborative thugs would hatch?

Hard To Misuse

I’ve seen the programming advice “design interfaces to be hard to misuse” repeated many times by many different gurus over the years. Because of this personal experience, I just auto-assumed (which is not a smart thing to do!) all experienced C++ developers: knew it, took it to heart, and thought twice before violating it.

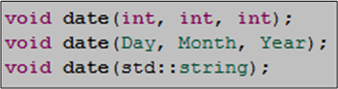

Check out the three date() function prototype declarations below. If you were responsible for designing and implementing the function for a library that would be used by your team mates, which interface would you choose to offer up to your users? Which one do you think is the “hardest to misuse“, and why?

Dissin’ Boost

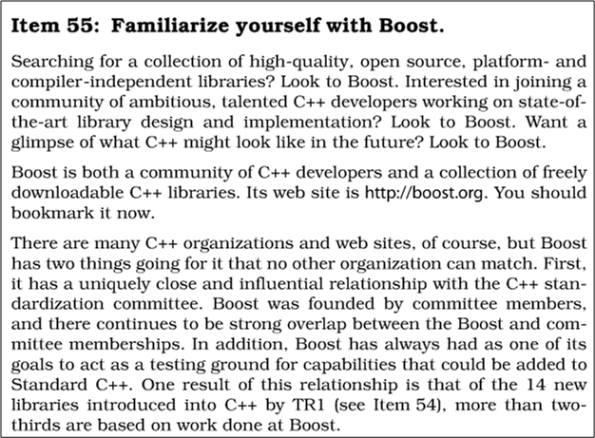

To support my yearning for learning, I continuously scan and probe all kinds of forums, books, articles, and blogs for deeper insights into, and mastery of, the C++ programming language. In all my external travels, I’ve never come across anyone in the C++ community that has ever trashed the boost libraries. Au contraire, every single reference that I’ve ever seen has praised boost as a world class open source organization that produces world class, highly efficient code for reuse. Here’s just one example of praise from Scott Meyers‘ classic “Effective C++: 55 Specific Ways To Improve Your Programs And Designs“:

Notice that in the first paragraph, I wrote the word external in bold. Internal, which means “at work” where politics is always involved, is another story. Sooooo, let me tell you one.

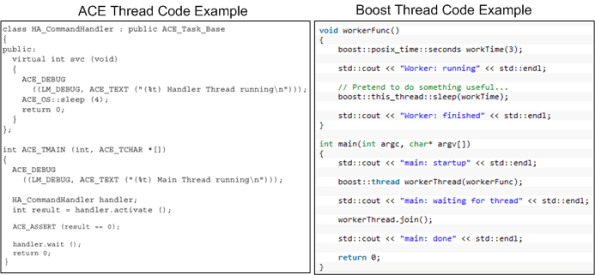

Years ago, a smart, highly productive, and dedicated developer who I respect started building a distributed “framework” on top of the ACE library set (not as a formal project – on his own time). There’s no doubt that ACE is a very powerful, robust, and battle-tested platform. However, because it was designed back in the days when C++ compiler technology was immature, I think its API is, let’s say “frumpy“, unconventional, and (dare I say) “obsolete” compared to the more modern Boost APIs. Boost-based code looks like natural C++, whereas ACE-based code looks like a macro derived dialect. In the functional areas where ACE and Boost overlap (which IMHO is large), I think that Boost is head over heels easier to learn and use. But that’s just me, and if you’re a long-time ACE advocate you might be mad at me now because you’re blinded by your bias – just like I am blinded by mine.

Fast forward to the present moment after other groups in the company (essentially, having no choice) have built their one-off applications on top of the homegrown, ACE-based, framework. Of course, you know through experience that “homegrown” means:

- the framework API is poorly documented,

- the build process is poorly documented,

- forks have been spawned because of the lack of a formally funded maintenance team and change process,

- the boundary between user and library code is jagged/blurry,

- example code tutorials are non-existent.

- it is most likely to cost less to build your own, lighter weight framework from scratch than to scale the learning curve by studying tens of 1,000s of lines of framework code to separate the API from the implementation and figure out how to use the dang thing.

Despite the time-proven assertions above, the framework author and a couple of “other” promoters who’ve never even tried to extract/build the framework, let alone learn the basics of the “jagged” API and write a simple sample distributed app on top of it, have naturally auto-assumed that reusing the framework in all new projects will save the company time and money.

Along comes a new project in which the evil Bulldozer00 (BD00) is a team member. Being suspicious of the internal marketing hype, and in response to the “indirect pressure and unspoken coercion” to architect, design, and build on top of the one and only homegrown framework, BD00 investigates the “product“. After spending the better part of a week browsing the code base and frustratingly trying to build the framework so that he could write a little distributed test app, BD00 gives up and concludes that the bulleted list definition above has withstood the test of time….. yet again.

When other members of BD00’s team, including one member who directly used the ACE-based framework on a previous project, investigate the qualities of the framework, they come to the same conclusion: thank you, but for our project, we’ll roll our own lighter weight, more targeted, and more “modern” framework on top of Boost. But of course, BD00 is the only politically incorrect and blatantly over-the-top rejector of the intended one-size-fits-all framework. In predictable cause-effect fashion, the homegrown framework advocates dig their heels in against BD00’s technical criticisms and step up their “cost and time savings” rhetoric – including a diss against Boost in their internal marketing materials. Hmmm.

Since application infrastructure is not a company core competence and certainly not a revenue generator, BD00 “cleverly” suggests releasing the framework into the open source community to test its viability and ability to attract an external following. The suggestion falls on deaf ears – of course. Even though BD00 (who’s deliberately evil foot-in-mouth approach to conflict-handling almost always triggers the classic auto-reject response in others) made the helpful(?) suggestion, the odds are that it would be ignored regardless of who had made it. Based on your personal experience, do you agree?

Note 1: If interested, check out this ACE vs Boost vs Poco libraries discussion on StackOverflow.com.

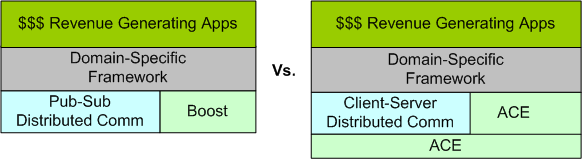

Note2: There’s a whole ‘nother sensitive socio-technical dimension to this story that may trigger yet another blog post in the future. If you’ve followed this blog, I’ve hinted about this bone of contention in several past posts. The diagram below gives a further hint as to its nature.

Idiomatic Idiot

Programming idioms are the language-specific, more concrete equivalent of design patterns. I remember watching a video interview with C++ creator Bjarne Stroustrup in which he recommended that programmers learn how to program idiomatically in 5, yes 5, different languages. WTF? I’ve been working in C++ for years now and it seemed like forever before I could comfortably program this way. There’s at least one whole book out there that teaches idiomatic programming in C++. Sheesh!

I think that to remain idiomatically competent in a language, one has got to work in the language almost daily for a long, sustained period of time. How can one do this with 5 languages? Maybe it’s just me – I am an Idiomatic Idiot.

How many languages could you confidently say you know how to program idiomatically in?

Access Change

To ensure consistency across our application component set in the team project that I’m currently working on, I’m required to inherit from a common base class that resides in a lower, infrastructure layer. However, since my class resides in the topmost, domain-specific layer of our stack, I want to discourage others from inheriting from it – but (as far as I know) there’s no simple way in C++ to do this (no contorted singletons please – it’s overkill).

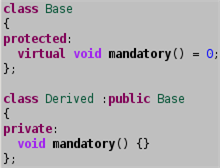

In addition to inserting a /*we’ll fire you if you inherit from this class!*/ type comment and removing the virtual keyword from all overridden member functions, I recently discovered an additional, trivial way of discouraging others from inheriting from a class that is intended to be a leaf in an inheritance tree. It may already be an existing C++ idiom that I haven’t stumbled across, but I’ll call it “access change” just in case it isn’t.

The figure below shows what I mean by “access change“. As you can see in the Derived class, in addition to leaving the virtual keyword out of the Derived::mandatory() function definition, I also changed its access qualifier from protected to private.

What do you think? Are there any downsides to this technique? Are there any other “gentle” ways to discourage, but not prevent, other C++ programmers from deriving from a class you wrote that wasn’t intended to be used as a base class?

The Language Of The Language

I found it amusing that “Gotcha” number 9 in Stephen Dewhurst’s wonderful “C++ Gotchas: Avoiding Common Problems in Coding and Design” is titled “Using Bad Language“. At first, I thought: “Come on, why require such stuffiness and rigid formality on matters so trivial?“. However, upon reflection, it does make sense that the careless abuse of the “language defining the language” can contribute to time being wasted and bugs being inserted and BBoMs being created.

Since it’s a powerful general purpose programming language, C++ is necessarily complex. Thus, it requires a creative mangling of the English language to carefully define C++’s features, syntax, semantics, and usage idioms. Understanding and memorizing this myriad of details in order to continuously move toward excellence is a time consuming process – no matter what those “Learn C++ in 24 hours” type books promise.

I consider myself a decent, intermediate level C++ programmer, but I’m constantly probing, sensing, and discovering new terms along with having to refresh my memory and understanding of “the language of the language“. How about you? Do you practice continuous learning and refreshment about your job and tool set?

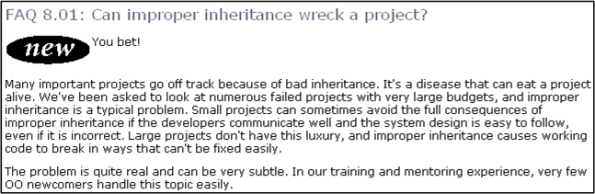

Improper Inheritance

Much like Improper Inheritance (II) can wreck family relationships, rampant II can also destroy a project after large and precious investments in time, money, and people have been committed. Before you know it, BAM! All of a sudden, you’ve noticed that you’re in BBoM city; not knowing how you got there and not knowing how to get the hell out of the indecipherable megalopolis.

Here’s what the “C++ FAQ” writers have to say on the II matter:

Here’s what Stephen Dewhurst says in “C++ Gotchas” number 92:

Use of public inheritance primarily for the purpose of reusing base class implementations in derived classes often results in unnatural, unmaintainable, and, ultimately, more inefficient designs.

Herb Sutter and Andrei Alexandrescu‘s chapter number 34 in “C++ Coding Standards: 101 Rules, Guidelines, and Best Practices” is titled “Prefer composition to inheritance“. Here’s a snippet from them:

Avoid inheritance taxes: Inheritance is the second-tightest coupling relationship in C++, second only to friendship. Inheritance is often overused, even by experienced developers. A sound rule of software engineering is to minimize coupling: If a relationship can be expressed in more than one way, use the weakest relationship that’s practical.

On page 19 in Design Patterns, the GoF state:

“Favoring object composition over class inheritance helps you keep each class encapsulated and focused on one task. Your classes and class hierarchies will remain small and will be less likely to grow into unmanageable monsters.”

Let’s explore this malarial scourge a little closer with a couple of dorky bulldozer00 design and code examples.

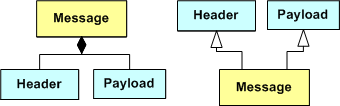

The UML class diagram pair below shows two ways of designing a message. It’s obvious that a message is composed of a header and payload (and maybe a trailer), no? Thus, you would think that the “has a” model on the left is a better mapping of a message structure in the (so-called) real world into the OO world than the multi “Is a” model on the right.

I don’t know about you, but I’ve seen many mini and maxi designs like this implemented in code during my long and undistinguished career. I’ve prolly unconsciously, or consciously but guiltily, hatched a few mini messes like this too.

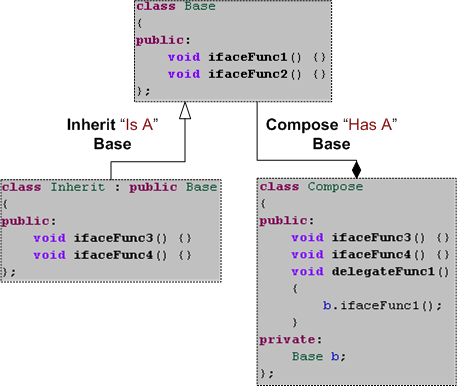

For our second, more concrete example, let’s look at the mixed design and code example below. Since the classes and member functions are so generic, it’s hard to decide which one is “better”, no?

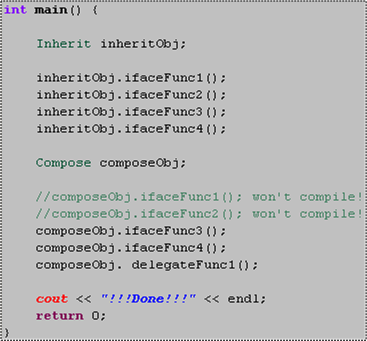

By looking at the test driver below, hopefully the “prefer composition to inheritance” heuristic should become apparent. The inheritance approach breaks encapsulation and exposes a “fatter” interface to client code, which in this case is the main() function. Fatter interfaces are more likely to be unknowingly abused by your code “users” than thinner interfaces – especially when specific call sequencing is required. With the composition approach, you can control how much wider the external interface is – by delegation. In this example, our designer has elected to expose only one of the two additional interface functions provided by the Base class – the ifaceFunc1() function.

Like all heuristics in programming and other technical fields of endeavor, there are always exceptions to the “prefer composition to inheritance” rule. This explains why you’ll see the word “prefer” in virtually all descriptions of heuristics. Even if you don’t see it, try to “think” it. An equivalent heuristic, “prefer acceptance to militancy“, perhaps should also hold true in the world of personal opinions, no?

C++ Dudes To Follow

If you’re a twit like me, and you also “do” C++, you might want to follow these people and resources on twitter:

They don’t tweet much, but when they do, they’re worth listening to. Do you know of any other C++ twitter resources that I should add to my list?

Performance Playground

Since I work on real-time software projects where tens of thousands of data samples per second must be filtered, manipulated, and transformed into higher level decision-support information, performance in the main processing pipeline is important. If the software can’t keep up with the unrelenting onslaught of data streaming in from the “real world“, internal buffers/queues will overflow at best and the system will crash at worst. D’oh!

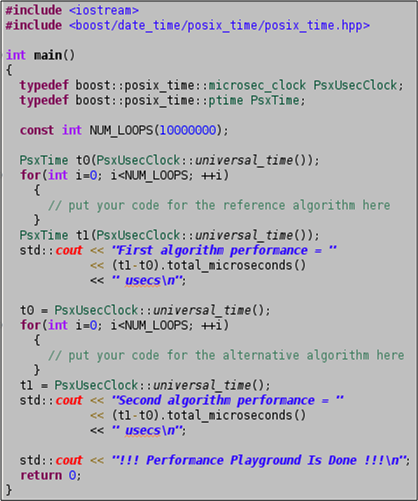

Because of the elevated importance of efficiency in real-time systems, I always keep a simple (one source code file) project named “performance_playground” open in my Eclipse IDE for algorithm/idiom/pattern prototyping and performance measurement. I use it to measure and optimize the performance of “chunks” of critical logic and to pit two or more candidates against each other in performance death matches. For each experiment I “branch” off of the project trunk and then I tag and commit the instantiation to archive the results.

The source code for the performance_playground project is shown below. The program’s sole external dependency is on the boost.date_time library for its platform-independent timestamping. Surely, you have the boost library set installed on all your development platforms, right?

How about you? Do you have something similar? Do you assume that all performance testing and algorithm vetting falls into the dreaded, time-wasting, “premature optimization” anti-pattern?

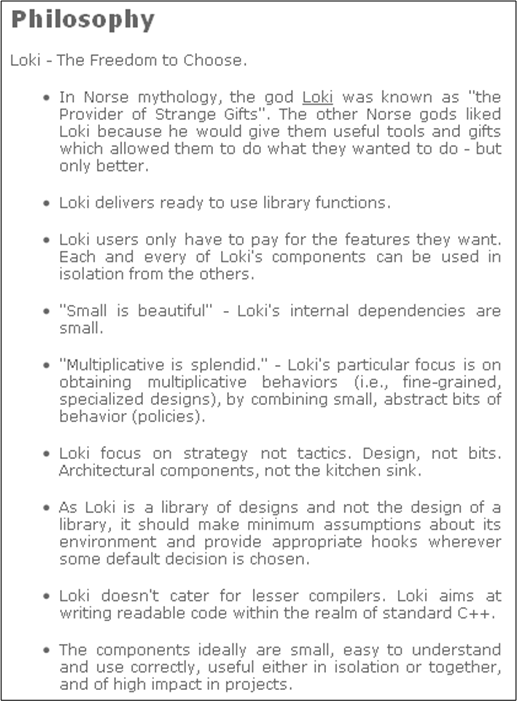

Loki Is Not Loco

Never heard of “Loki”? Check it out here: The Loki Library.

The Loki team has developed the best philosophy for programming library design that I’ve ever seen. It’s not so abstract that you can’t figure out what they mean, and they know that the real bang for the buck comes from disciplined dependency management and small, flat components. Judge for yourself:

How about you? Have you seen better?