Archive

Dissin’ Boost

To support my yearning for learning, I continuously scan and probe all kinds of forums, books, articles, and blogs for deeper insights into, and mastery of, the C++ programming language. In all my external travels, I’ve never come across anyone in the C++ community that has ever trashed the boost libraries. Au contraire, every single reference that I’ve ever seen has praised boost as a world class open source organization that produces world class, highly efficient code for reuse. Here’s just one example of praise from Scott Meyers‘ classic “Effective C++: 55 Specific Ways To Improve Your Programs And Designs“:

Notice that in the first paragraph, I wrote the word external in bold. Internal, which means “at work” where politics is always involved, is another story. Sooooo, let me tell you one.

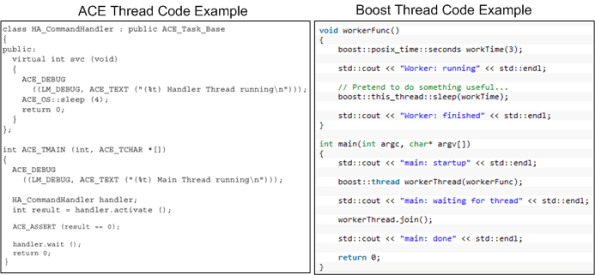

Years ago, a smart, highly productive, and dedicated developer who I respect started building a distributed “framework” on top of the ACE library set (not as a formal project – on his own time). There’s no doubt that ACE is a very powerful, robust, and battle-tested platform. However, because it was designed back in the days when C++ compiler technology was immature, I think its API is, let’s say “frumpy“, unconventional, and (dare I say) “obsolete” compared to the more modern Boost APIs. Boost-based code looks like natural C++, whereas ACE-based code looks like a macro derived dialect. In the functional areas where ACE and Boost overlap (which IMHO is large), I think that Boost is head over heels easier to learn and use. But that’s just me, and if you’re a long-time ACE advocate you might be mad at me now because you’re blinded by your bias – just like I am blinded by mine.

Fast forward to the present moment after other groups in the company (essentially, having no choice) have built their one-off applications on top of the homegrown, ACE-based, framework. Of course, you know through experience that “homegrown” means:

- the framework API is poorly documented,

- the build process is poorly documented,

- forks have been spawned because of the lack of a formally funded maintenance team and change process,

- the boundary between user and library code is jagged/blurry,

- example code tutorials are non-existent.

- it is most likely to cost less to build your own, lighter weight framework from scratch than to scale the learning curve by studying tens of 1,000s of lines of framework code to separate the API from the implementation and figure out how to use the dang thing.

Despite the time-proven assertions above, the framework author and a couple of “other” promoters who’ve never even tried to extract/build the framework, let alone learn the basics of the “jagged” API and write a simple sample distributed app on top of it, have naturally auto-assumed that reusing the framework in all new projects will save the company time and money.

Along comes a new project in which the evil Bulldozer00 (BD00) is a team member. Being suspicious of the internal marketing hype, and in response to the “indirect pressure and unspoken coercion” to architect, design, and build on top of the one and only homegrown framework, BD00 investigates the “product“. After spending the better part of a week browsing the code base and frustratingly trying to build the framework so that he could write a little distributed test app, BD00 gives up and concludes that the bulleted list definition above has withstood the test of time….. yet again.

When other members of BD00’s team, including one member who directly used the ACE-based framework on a previous project, investigate the qualities of the framework, they come to the same conclusion: thank you, but for our project, we’ll roll our own lighter weight, more targeted, and more “modern” framework on top of Boost. But of course, BD00 is the only politically incorrect and blatantly over-the-top rejector of the intended one-size-fits-all framework. In predictable cause-effect fashion, the homegrown framework advocates dig their heels in against BD00’s technical criticisms and step up their “cost and time savings” rhetoric – including a diss against Boost in their internal marketing materials. Hmmm.

Since application infrastructure is not a company core competence and certainly not a revenue generator, BD00 “cleverly” suggests releasing the framework into the open source community to test its viability and ability to attract an external following. The suggestion falls on deaf ears – of course. Even though BD00 (who’s deliberately evil foot-in-mouth approach to conflict-handling almost always triggers the classic auto-reject response in others) made the helpful(?) suggestion, the odds are that it would be ignored regardless of who had made it. Based on your personal experience, do you agree?

Note 1: If interested, check out this ACE vs Boost vs Poco libraries discussion on StackOverflow.com.

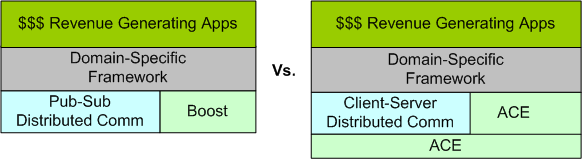

Note2: There’s a whole ‘nother sensitive socio-technical dimension to this story that may trigger yet another blog post in the future. If you’ve followed this blog, I’ve hinted about this bone of contention in several past posts. The diagram below gives a further hint as to its nature.

Recursive Interpretation

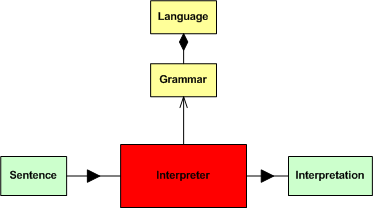

In their classic book, Design Patterns, the GoF defines the intent of the Interpreter pattern as:

Given a language, define a representation for its grammar along with an interpreter that uses the representation to interpret sentences in the language.

For your viewing pleasure, and because it’s what I like to do, I’ve translated (hopefully successfully) the wise words above into the SysML block diagram below.

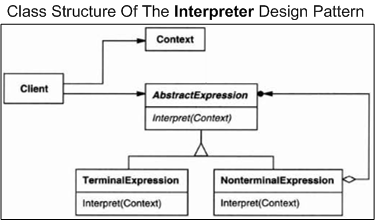

Moving on, observe the copied-and-pasted pseudo-UML class diagram of the GoF Interpreter design pattern below. In a nutshell, the “client” object builds and initializes the context of the sentence to be interpreted and invokes the interpret() operation – passing a reference to the context (in the form of a syntax tree) down into the concrete “xxxExpression” interpreter objects in a recursive descent so that they can do their piece of the interpretation work and then propagate the results back up the stack.

In their writeup of the Interpreter design pattern, the GoF state:

Terminal nodes generally don’t store information about their position in the abstract syntax tree. Parent nodes pass them whatever context they need during interpretation. Hence there is a distinction between shared (intrinsic) state and passed-in (extrinsic) state.

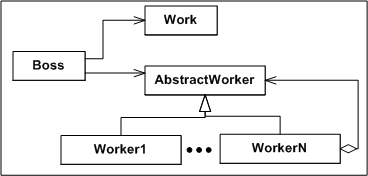

Since the classes in the Interpreter design pattern aren’t thinking, feeling, scheming humans concerned about status and looking good, the collection of collaborating classes do their jobs effectively and efficiently, just like mindless machines should. However, if you try to implement the Interpreter pattern on a project team with human “objects”, fuggedabout it. To start with, the “client” object (i.e. the boss) at the top of the recursion sequence won’t know how to create a coherent sentence or context. Even if the boss does do it, he/she may intentionally or unitentionally withhold the context from the recursion chain and invoke the interpret() operation of the first “XXXExpression” object (i.e. worker) with garbage. When the final interpretation of the garbled sentence is returned to the boss, it’s a new form of useless garbage.

On it’s way down the stack, at any step in the recursive descent, the propagated context can be distorted or trashed on purpose by self-serving intermediate managers and workers. Unlike a software system composed of mindless objects working in lock-step to solve a problem, the chances that the work will be done right, or even defined right, is miniscule in a DYSCO.

Improper Inheritance

Much like Improper Inheritance (II) can wreck family relationships, rampant II can also destroy a project after large and precious investments in time, money, and people have been committed. Before you know it, BAM! All of a sudden, you’ve noticed that you’re in BBoM city; not knowing how you got there and not knowing how to get the hell out of the indecipherable megalopolis.

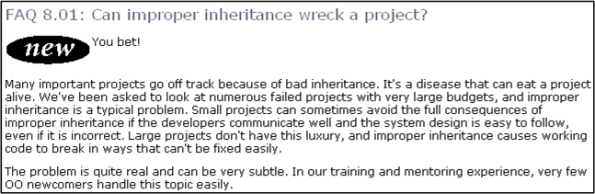

Here’s what the “C++ FAQ” writers have to say on the II matter:

Here’s what Stephen Dewhurst says in “C++ Gotchas” number 92:

Use of public inheritance primarily for the purpose of reusing base class implementations in derived classes often results in unnatural, unmaintainable, and, ultimately, more inefficient designs.

Herb Sutter and Andrei Alexandrescu‘s chapter number 34 in “C++ Coding Standards: 101 Rules, Guidelines, and Best Practices” is titled “Prefer composition to inheritance“. Here’s a snippet from them:

Avoid inheritance taxes: Inheritance is the second-tightest coupling relationship in C++, second only to friendship. Inheritance is often overused, even by experienced developers. A sound rule of software engineering is to minimize coupling: If a relationship can be expressed in more than one way, use the weakest relationship that’s practical.

On page 19 in Design Patterns, the GoF state:

“Favoring object composition over class inheritance helps you keep each class encapsulated and focused on one task. Your classes and class hierarchies will remain small and will be less likely to grow into unmanageable monsters.”

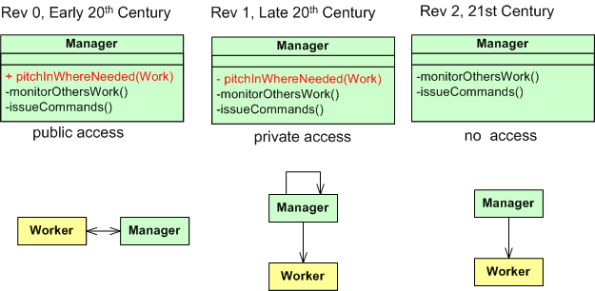

Let’s explore this malarial scourge a little closer with a couple of dorky bulldozer00 design and code examples.

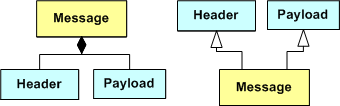

The UML class diagram pair below shows two ways of designing a message. It’s obvious that a message is composed of a header and payload (and maybe a trailer), no? Thus, you would think that the “has a” model on the left is a better mapping of a message structure in the (so-called) real world into the OO world than the multi “Is a” model on the right.

I don’t know about you, but I’ve seen many mini and maxi designs like this implemented in code during my long and undistinguished career. I’ve prolly unconsciously, or consciously but guiltily, hatched a few mini messes like this too.

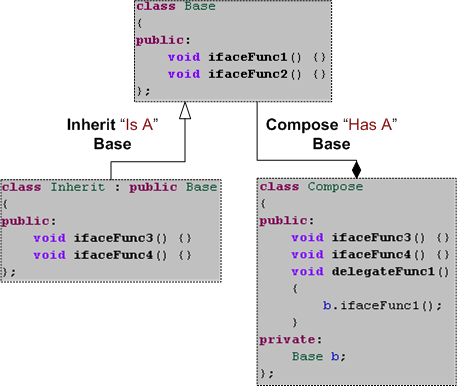

For our second, more concrete example, let’s look at the mixed design and code example below. Since the classes and member functions are so generic, it’s hard to decide which one is “better”, no?

By looking at the test driver below, hopefully the “prefer composition to inheritance” heuristic should become apparent. The inheritance approach breaks encapsulation and exposes a “fatter” interface to client code, which in this case is the main() function. Fatter interfaces are more likely to be unknowingly abused by your code “users” than thinner interfaces – especially when specific call sequencing is required. With the composition approach, you can control how much wider the external interface is – by delegation. In this example, our designer has elected to expose only one of the two additional interface functions provided by the Base class – the ifaceFunc1() function.

Like all heuristics in programming and other technical fields of endeavor, there are always exceptions to the “prefer composition to inheritance” rule. This explains why you’ll see the word “prefer” in virtually all descriptions of heuristics. Even if you don’t see it, try to “think” it. An equivalent heuristic, “prefer acceptance to militancy“, perhaps should also hold true in the world of personal opinions, no?

Avoiding The Big Ball Of Mud

Like other industries, the software industry is rife with funny and quirky language terms. One of my favorites is “Big Ball of Mud“, or BBoM. A BBoM is a mess of a software system that starts off soft and malleable but turns brittle and unstable over time. Inevitably, it hardens like a ball of mud baking in the sun; ready to crumble and wreak havoc on the stakeholder community when disturbed. D’oh!

“And they looked upon the SW and saw that it was good. But they just had to add one more feature…”

Joseph Yoder, one of the co-creators of “BBoM” along with Brian Foote, recently gave a talk titled “Big Balls of Mud in Agile Development: Can We Avoid Them?“. Out of curiosity and the desire to learn more, I watched a video of the talk at InfoQ. In his talk, Mr. Yoder listed these agile tenets as “possible” BBoM promoters:

- Lack of upfront design (i.e. BDUF)

- Embrace late changes to requirements

- Continuous evolving architecture

- Piecemeal growth

- Focus on (agile) process instead of architecture

- Working code is the one true measure of success

For big software systems, steadfastly adhering to these process principles can hatch a BBoM just as skillfully as following a sequential and prescriptive waterfall process. It’ll just get you to the state of poverty that always accompanies a BBoM much quicker.

Unlike application layer code, infrastructure code should not be expected to change often. Even small architectural changes can have far reaching negative effects on all the value-added application code that relies on the structure and general functionality provided under the covers. If you look hard at Joe’s list, any one of his bullets can insidiously steer a team off the success profile below – and lead the team straight to BBoM hell.

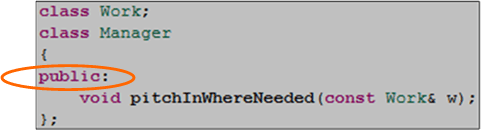

void Manager::pitchInWhereNeeded(const Work& w){}

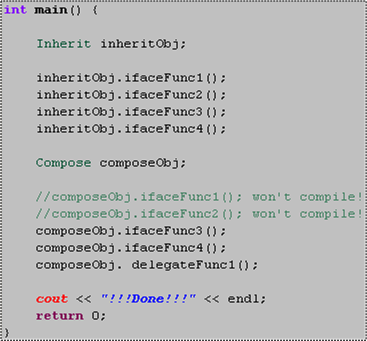

Unless you’re a C++ programmer, you probably won’t understand the title of this post. It’s the definition of the “pitchInWhereNeeded” member function of a “Manager” class. If you look around your immediate vicinity with open eyes, that member function is most likely missing from your Manager class definition. If you’re a programmer, oops, I mean a software engineer, it’s probably also missing from your derived “SoftwareLead“, “SoftwareProjectManager“, and “SoftwareArchitect” classes too.

As the UML-annotated figure below shows, in the early twentieth century the “pitchInWhereNeeded” function was present and publicly accessible by other org objects. On revision number 1 of the “system”, as signaled by the change from “+” to “-“, its access type was changed to private. This seemingly minor change broke all existing “system” code and required all former users of the class to redesign and retest their code. D’oh!

On the second revision of the Manager class, this critical, system-trust-building member function mysteriously disappeared completely. WTF?. This rev 2 version of the code didn’t break the system, but the system’s responsiveness decreased since private self -calls by manager objects to the “pitchInWhereNeeded” function were deleted and more work was pushed back into the “other” system objects. Bummer.

Bugs Or Cash

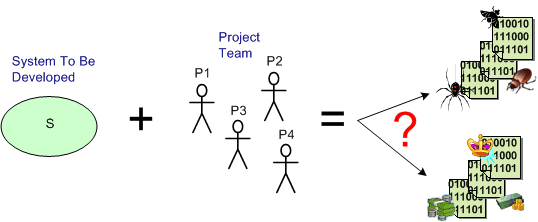

Assume that you have a system to build and a qualified team available to do the job. How can you increase the chance that you’ll build an elegant and durable money maker and not a money sink that may put you out of business.

The figure below shows one way to fail. It’s the well worn and oft repeated ready-fire-aim strategy. You blast the team at the project and hope for the best via the buzz phrase of the day – “emergent design“.

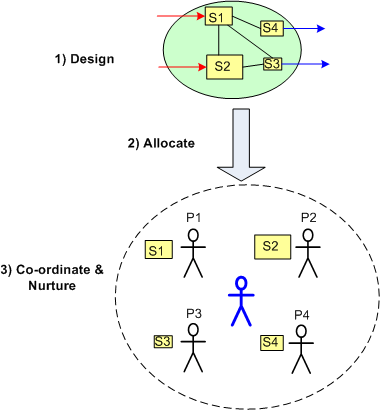

On the other hand, the figure below shows a necessary but not sufficient approach to success: design-allocate-coordinate. BTW, the blue stick dude at the center, not the top, of the project is you.

On the other hand, the figure below shows a necessary but not sufficient approach to success: design-allocate-coordinate. BTW, the blue stick dude at the center, not the top, of the project is you.

Start Big?

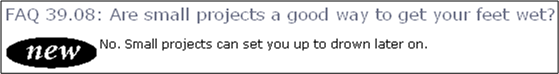

While browsing through the “C++ FAQs“, this particular FAQ caught my eye:

The authors’ “No” answer was rather surprising to me at first because I had previously thought the answer was an obvious “Yes“. However, the rationale behind their collective “No” was compelling. Rather than butcher and fragment their answer with a cut and paste summary, I present their elegant and lucid prose as is:

Small projects, whose intellectual content can be understood by one intelligent person, build exactly the wrong skills and attitudes for success on large projects…..The experience of the industry has been that small projects succeed most often when there are a few highly intelligent people involved who use a minimum of process and are willing to rip things apart and start over when a design flaw is discovered. A small program can be desk-checked by senior people to discover many of the errors, and static type checking and const correctness on a small project can be more grief than they are worth. Bad inheritance can be fixed in many ways, including changing all the code that relied on the base class to reflect the new derived class. Breaking interfaces is not the end of the world because there aren’t that many interconnections to start with. Finally, source code control systems and formalized build procedures can slow down progress.

On the other hand, big projects require more people, which implies that the average skill level will be lower because there are only so many geniuses to start with, and they usually don’t get along with each other that well, anyway. Since the volume of code is too large for any one person to comprehend, it is imperative that processes be used to formalize and communicate the work effort and that the project be decomposed into manageable chunks. Big programs need automated help to catch programming errors, and this is where the payback for static type checking and const correctness can be significant. There is usually so much code based on the promises of base classes that there is no alternative to following proper inheritance for all the derived classes; the cost of changing everything that relied on the base class promises could be prohibitive. Breaking an interface is a major undertaking, because there are so many possible ripple effects. Source code control systems and formalized build processes are necessary to avoid the confusion that arises otherwise.

So the issue is not just that big projects are different. The approaches and attitudes to small and large projects are so diametrically opposed that success with small projects breeds habits that do not scale and can lead to failure of large projects.

After reading this, I initially changed my previously un-investigated opinion. However, upon further reflection, a queasy feeling arose in my stomach because the implication of the authors is that the code bases on big projects aren’t as messy and undisciplined as smaller projects. Plus, it seems as though they imply that disciplined use of processes and tools have a strong correlation with a clean code base and that developers, knowing that the system will be large, will somehow change their behavior. My intuition and personal experience tell me that this may not be true, especially for large code bases that have been around for a long time and have been heavily hacked by lots of programmers (both novice and expert) under schedule pressure.

Small projects may set you up to drown later on, but big projects may start to drown you immediately. What are your thoughts, start small or big?

Fixed Vs Variable Sleep Times

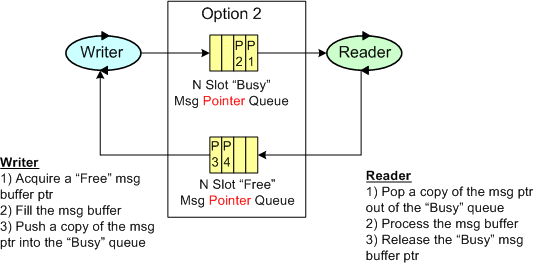

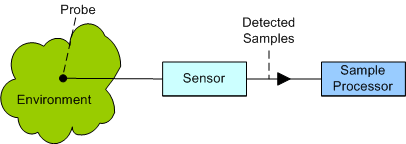

Consider the back end of a sensor system as shown below. Now, assume that you’re tasked with building the Sample Processor and you need some way of testing it. Thus, you need to simulate the continuous high speed sample stream that the Sensor will produce during operation in the real physical world.

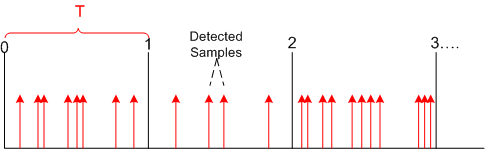

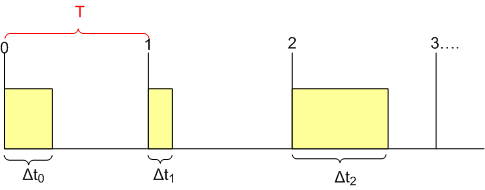

Since the analog real world is wonderfully messy and non-deterministic, the sensor/probe combo will produce data sample detections in bursty clumps as modeled below.

However, since you don’t need the high fidelity and fine grained controllability in your sensor simulator implied by the figure, you simplify your approach by modeling the sensor output as a deterministically time sliced (slice size = T) and “batched” device as shown by the yellow boxes in the diagram below.

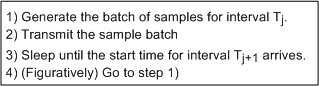

After thinking about it, you sketch out a simple core sensor simulation algorithm as:

After thinking about it, you sketch out a simple core sensor simulation algorithm as:

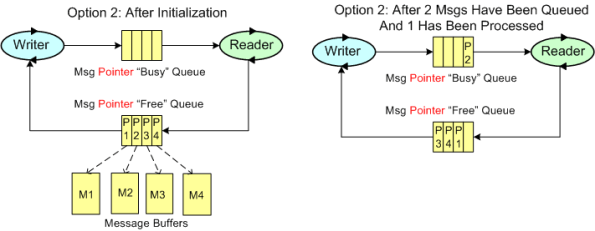

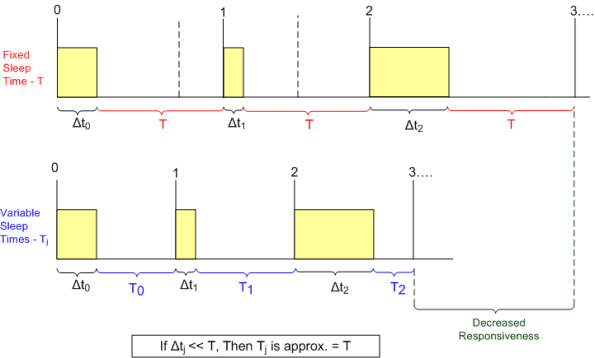

As the figure below shows, there are two options for determining how long to “sleep” after each yellow sample batch has been generated and transmitted: fixed and variable. In the simpler approach, the code sleeps for a fixed time duration “T” after every batch – regardless of how long it took to generate and transmit the batch of sensor samples. In the higher fidelity variable sleep approach, the time to sleep is calculated on the fly during runtime as the slice time “T” minus the time it took to generate and send the current batch. As the batch processing time approaches the time slice period T, the software sleeps less in order to maintain true real-time operation.

As the figure shows, implementing the sensor simulator with variable sleep time logic results in truer real-time behavior. In the fixed sleep design, the simulator starts lagging behind real-time immediately and the longer the sensor simulator runs, the further its behavior deviates from the real-time ideal. However, for short simulator runs and/or large relative time slice periods (see the box above), the simpler fixed sleep time approach tracks real-time just about as well.

For the project I’m currently working on, I’ve coded up a sensor simulator and sample processor pair that can be configured either way. I just thought I’d share the analysis/design thought process that I went through just in case it might interest or help anybody who’s working on something similar.

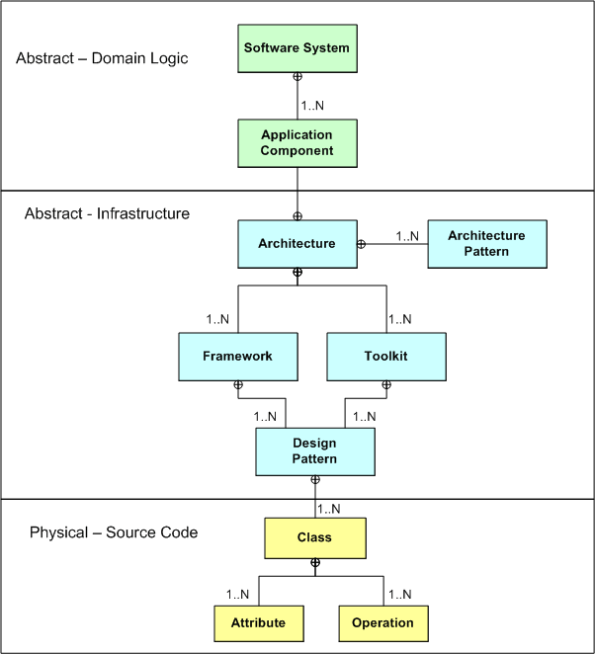

Domain, Infrastructure, And Source

Via a simple SysML diagram that solely uses the “contains” relationship icon (the circled crosshairs thingy) , here’s Bulldozeroo’s latest attempt to make sense of the relationships between various levels of abstraction in the world of software as he knows it today. Notice that in Bulldozer00’s world, where the sky is purple, the architecture is at the center of the containment hierarchy.