Archive

Spike To Learn

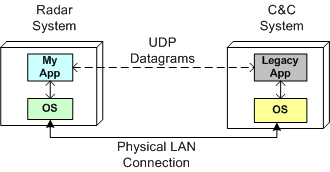

As one of the responsibilities on my last project, I had to interface one of our radars to a 10+ year old, legacy, command-and-control system built by another company. My C++11 code was required to receive commands from the control system and send radar data to it via UDP datagrams over a LAN that connects the two systems together.

It’s unfortunate, but we won’t get a standard C++ networking library until the next version of the C++ standard gets ratified in 2017. However, instead of using the low-level C sockets API to implement the interface functionality, I chose to use the facilities of the Poco::Net library.

Poco is a portable, well written, and nicely documented set of multi-function, open source C++ libraries. Among other nice, higher level, TCP/IP and http networking functionality, Poco::Net provides a thin wrapper layer around the native OS C-language sockets API.

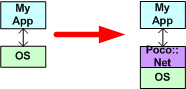

Since I had never used the Poco::Net API before, I decided to spike off the main trail and write a little test program to learn the API before integrating the API calls directly into my production code. I use the “Spike To Learn” best practice whenever I can.

Here is the finished and prettied-up spike program for your viewing pleasure:

#include <string>

#include <iostream>

#include "Poco/Net/SocketAddress.h"

#include "Poco/Net/DatagramSocket.h"

using Poco::Net::SocketAddress;

using Poco::Net::DatagramSocket;

int main() {

//simulate a UDP legacy app bound to port 15001

SocketAddress legacyNodeAddr{"localhost", 15001};

DatagramSocket legacyApp{legacyNodeAddr}; //create & bind

//simulate my UDP app bound to port 15002

SocketAddress myAddr{"localhost", 15002};

DatagramSocket myApp{myAddr}; //create & bind

//myApp creates & transmits a message

//encapsulated in a UDP datagram to the legacyApp

char myAppTxBuff[]{"Hello legacyApp"};

auto msgSize = sizeof(myAppTxBuff);

myApp.sendTo(myAppTxBuff,

msgSize,

legacyNodeAddr);

//legacyApp receives a message

//from myApp and prints its payload

//to the console

char legacyAppRxBuff[msgSize];

legacyApp.receiveBytes(legacyAppRxBuff, msgSize);

std::cout << std::string{legacyAppRxBuff}

<< std::endl;

//legacyApp creates & transmits a message

//to myApp

char legacyAppTxBuff[]{"Hello myApp!"};

msgSize = sizeof(legacyAppTxBuff);

legacyApp.sendTo(legacyAppTxBuff,

msgSize,

myAddr);

//myApp receives a message

//from legacyApp and prints its payload

//to the console

char myAppRxBuff[msgSize];

myApp.receiveBytes(myAppRxBuff, msgSize);

std::cout << std::string{myAppRxBuff}

<< std::endl;

}

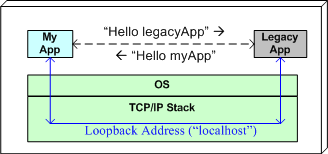

As you can see, I used the Poco::Net::SocketAddress and Poco::Net::DatagramSocket classes to simulate the bi-directional messaging between myApp and the legacyApp on one machine. The code first transmits the text message “Hello legacyApp!” from myApp to the legacyApp; and then it transmits the text message “Hello myApp!” from the legacyApp to myApp.

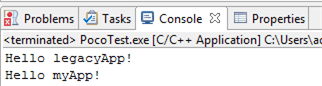

Lest you think the program doesn’t work 🙂 , here is the console output after the final compile & run cycle:

As a side note, notice that I used C++11 brace-initializers to uniformly initialize every object in the code – except for one: the msgSize object. I had to fallback and use the “=” form of initialization because “auto” does not yet play well with brace-initializers. For who knows why, the type of obj in a statement of the form “auto obj{5};” is deduced to be a std::initializer_list<T> instead of a simple int. I think this strange inconvenience will be fixed in C++17. It may have been fixed already in the recently ratified C++14 standard, but I don’t know for sure. Do you?

A Grain Of Salt

Somehow, I stumbled upon an academic paper that compares programming language performance in the context of computing the results for a well-known, computationally dense, macro-economics problem: “the stochastic neoclassical growth model“. Since the results hoist C++ on top of the other languages, I felt the need to publish the researchers’ findings in this blog post :). As with all benchmarks, take it with a grain of salt because… context is everything.

Qualitative Findings

Quantitative Findings

The irony of this post is that I’m a big fan of Nassim Taleb, whose lofty goal is to destroy the economics profession as we know it. He thinks all the fancy, schmancy mathematical models and metrics used by economists (including famous Nobel laureates) to predict the future are predicated on voodoo science. They cause more harm than good by grossly misrepresenting and underestimating the role of risk in their assumptions and derived equations.

FUNGENOOP Programming

As you might know, the word “paradigm” and the concept of a “paradigm shift” were made insanely famous by Thomas Kuhn’s classic book: “The Structure Of Scientific Revolutions“. Mr. Kuhn’s premise is that science only advances via a progression of funerals. An old, inaccurate view of the world gets supplanted by a new, accurate view only when the powerfully entrenched supporters of the old view literally die off. The implication is that a paradigm shift is a binary, black and white event. The old stuff has been proven “wrong“, so you’re compelled to totally ditch it for the new “right” stuff – lest you be ostracized for being out of touch with reality.

In his recent talks on C++, Bjarne Stroustrup always sets aside a couple of minutes to go off on a mini-rant against “paradigm shifts“. Even though Einstein’s theory of relativity subsumes Newton’s classical physics, Newtonian physics is still extremely useful to practicing engineers. The discovery of multiplication/division did not make addition/subtraction useless. Likewise, in the programming world, the meteoric rise of the “object-oriented” programming style (and more recently, the “functional” programming style) did not render “procedural” and/or “generic” programming techniques totally useless.

This slide below is Bjarne’s cue to go off on his anti-paradigm rant.

If the system programming problem you’re trying to solve maps perfectly into a hierarchy of classes, then by all means use a OOP-centric language; perhaps Java, Smalltalk? If statefulness is not a natural part of your problem domain, then preclude its use by using something like Haskell. If you’re writing algorithmically simple but arcanely detailed device drivers that directly read/write hardware registers and FIFOs, then perhaps use procedural C. Otherwise, seriously think about using C++ to mix and match programmimg techniques in the most elegant and efficient way to attack your “multi-paradigm” system problem. FUNGENOOP (FUNctional + GENeric + Object Oriented + Procedural) programming rules!

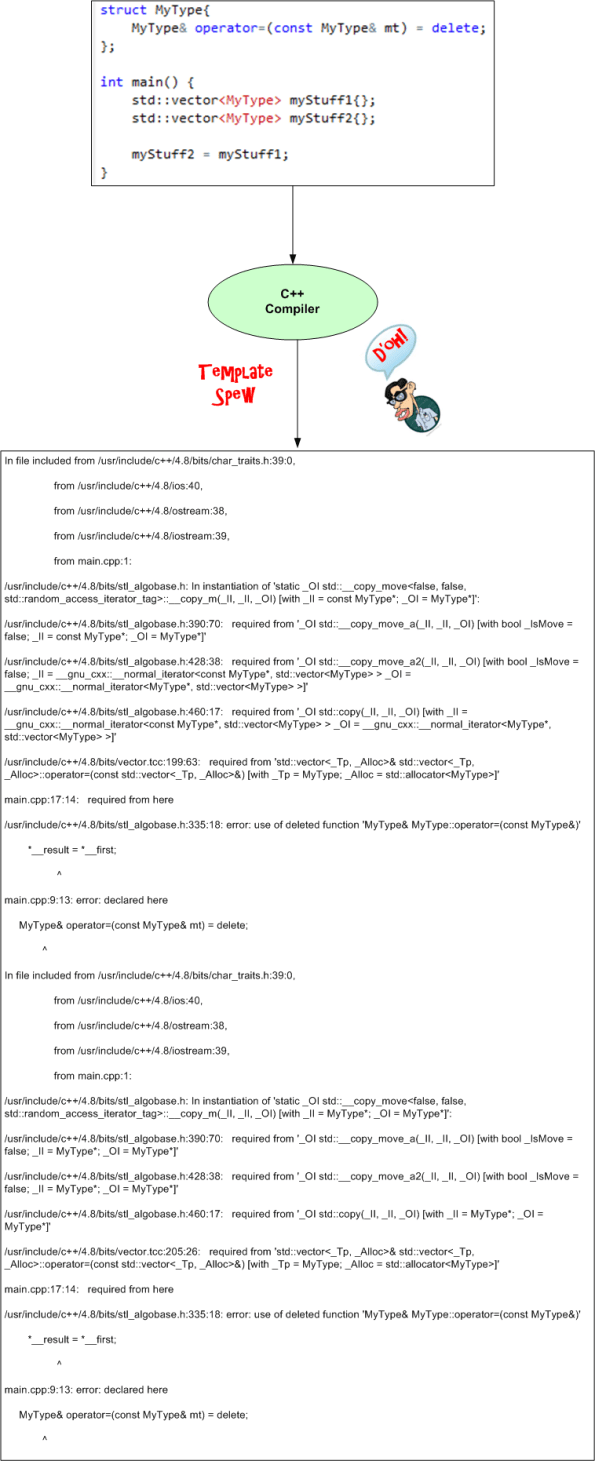

Stopping The Spew!

Every C++ programmer has experienced at least one, and most probably many, “Template Spew” (TS) moments. You know you’ve triggered a TS moment when, just after hitting the compile button on a program the compiler deems TS-worthy, you helplessly watch an undecipherable avalanche of error messages zoom down your screen at the speed of light. It is rumored that some novices who’ve experienced TS for the very first time have instantaneously entered a permanent catatonic state of unresponsiveness. It’s even said that some poor souls have swan-dived off of bridges to untimely deaths after having seen such carnage.

Note: The graphic image that follows may be highly disturbing. You may want to stop reading this post at this point and continue to waste company time by surfing over to facebook, reddit, etc.

TS occurs when one tries to use a templated class object or function template with a template parameter type that doesn’t provide the behavior “assumed” by the class or function. TS is such a scourge in the C++ world that guru Scott Meyers dedicates a whole item in “Effective STL“, number 49, to handling the trauma associated with deciphering TS gobbledygook.

For those who’ve never seen TS output, here is a woefully contrived example:

The above example doesn’t do justice to the havoc the mighty TS dragon can wreak on the mind because the problem (std::vector<T> requires its template arg to provide a copy assignment function definition) can actually be inferred from a couple of key lines in the sea of TS text.

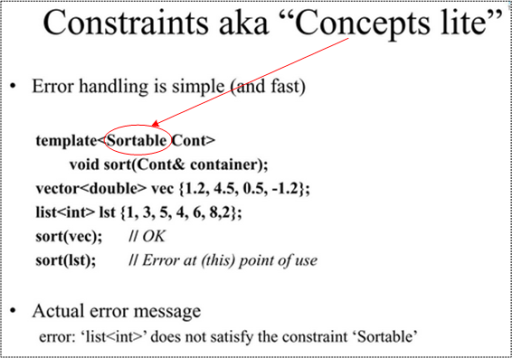

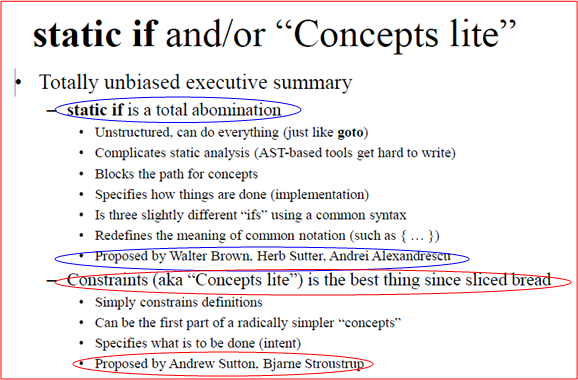

Ok, enough doom and gloom. Fear not, because help is on the way via C++14 in the form of “concepts lite“. A “concept” is simply a predicate evaluated on a template argument at compile time. If you employ them while writing a template, you inform the compiler of what kind(s) of behavior your template requires from its argument(s). As a use case illustration, behold this slide from Bjarne Stroustrup:

The “concept” being highlighted in this example is “Sortable“. Once the compiler knows that the sort<T> function requires its template argument to be “Sortable“, it checks that the argument type is indeed sortable. If not, the error message it emits will be something short, sweet, and to the point.

The concept of “concepts” has a long and sordid history. A lot of work was performed on the feature during the development of the C++11 specification. However, according to Mr. Stroustrup, the result was overly complicated (concept maps, new syntax, scope & lookup issues). Thus, the C++ standards committee decided to controversially sh*tcan the work:

C++11 attempt at concepts: 70 pages of description, 130 concepts – we blew it!

After regrouping and getting their act together, the committee whittled down the number of pages and concepts to something manageable enough (approximately 7 pages and 13 concepts) to introduce into C++14. Hence, the “concepts lite” label. Hopefully, it won’t be long before the TS dragon is relegated back to the dungeon from whence it came.

C++1y Automatic Type Deduction

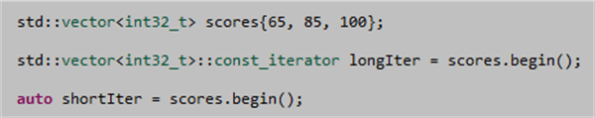

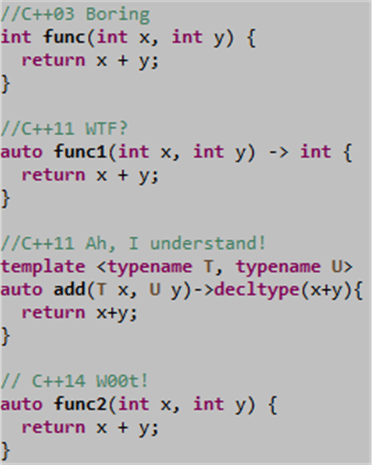

The addition, err, redefinition of the auto keyword in C++11 was a great move to reduce code verbosity during the definition of local variables:

In addition to this convenient usage, employing auto in conjunction with the new (and initially weird) function-trailing-return-type syntax is useful for defining function templates that manipulate multiple parameterized types (see the third entry in the list of function definitions below).

In the upcoming C++14 standard, auto will also become useful for defining normal, run-of-the-mill, non-template functions. As the fourth entry below illustrates, we’ll be able to use auto in function definitions without having to use the funky function-trailing-return-type syntax (see the useless, but valid, second entry in the list).

For a more in depth treatment of C++11’s automatic type deduction capability, check out Herb Sutter’s masterful post on the new AAA (Almost Always Auto) idiom.

C++11 Annoyance Avoiders

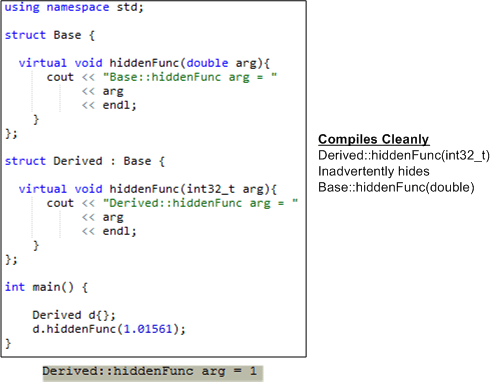

I’ve always been torn as to whether or not to annotate derived class member functions intended to override base class members as virtual. Even though it’s unnecessary to do so, I have always preferred to declare them as virtual because it’s just another little reminder to me (besides the colon followed by the base class name at the top of the class definition) that the class I’m coding up is indeed a derived one.

With the introduction of the context-sensitive “override” keyword into C++11, I’ve decided that I’m still going to annotate overriding derived class member functions as a reminder of a class’s derived-ness. However, instead of adorning them with virtual, I’m going to use override instead. Even though they serve basically the same purpose, the compiler uses override to preclude inadvertent hiding of base class member functions that are intended to be overridden.

Assume that the writer of the Derived class below intended to override Base::hiddenFunc(double) but mistakenly wrote Derived::hiddenFunc(int32_t) instead. As you can see from the console output below the code graphic, a loss of precision occurs whenever a user of Derived calls hiddenFunc with a double.

By using override instead of virtual, the potential “gotcha” is avoided. Because the use of override explicity tells the compiler of the programmer’s intention to override, and not hide, Base::hiddenFunc, the code below doesn’t even compile.

C++11 and C++14 provide lots of little, conscientious, “annoyance avoiders” like override (auto, brace initialization, nullptr, lambdas, std::array, smart pointers, etc). Thanks to the benevolent stewardship of Stroustrup/Sutter and the rest of the ISO WG21 C++ committee membership, these little gems make programming in the language more intrinsically rewarding and safer than it is now. If you’re not a hard core anti-C++ zealot, then maybe now is the time time to give the language a try.

Staying Sane

Standardization is long periods of mind-numbing boredom interrupted by moments of sheer terror – Bjarne Stroustrup

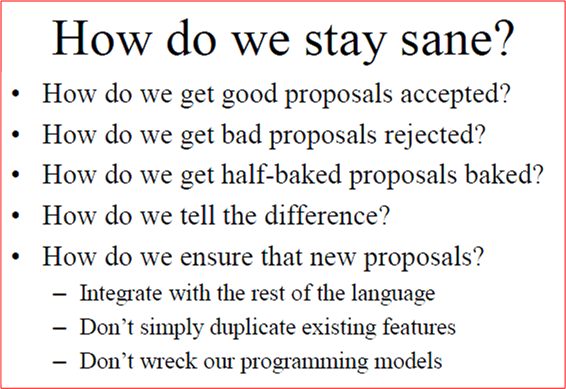

In his ACCU2013 talk, “C++14 Early Thoughts“, Bjarne Stroustrup presented this slide:

By using “we” in each bullet point, Bjarne was referring to the ISO WG-1 C++ committee and the daunting challenges it faces to successfully move the language forward.

Not only do the committee leaders have to manage the external onslaught of demands from a huge, dedicated user base, they have to homogenize the internal communications amongst many smart and assertive members. To illustrate the internal management problem, Bjarne said something akin to: “There is no topic the committee isn’t willing to discuss at length for two years“.

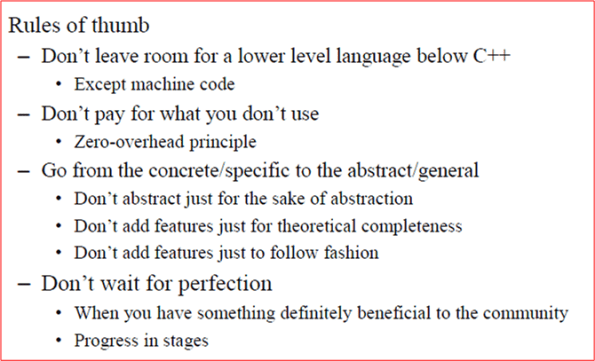

In order to prevent being overwhelmed with work, the committee uses this set of grass roots principles to filter out the incoming chaff from the wheat:

I have no idea how internal conflicts are handled, nor how infinite loops of technical debate are exited, but since the all-volunteer committee is still functioning and doing a great job (IMO) of modernizing the language, there’s got to be some magic at work here:

The Right Tool For The Job

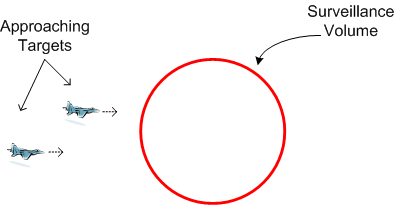

The figure below depicts a scenario where two targets are just about to penetrate the air space covered by a surveillance radar.

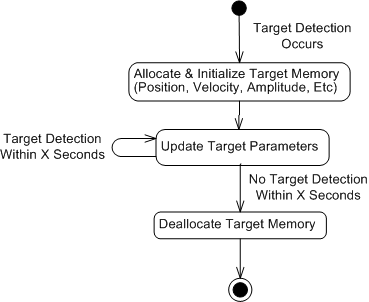

The next sequence of snapshots illustrates the targets entering, traversing, and exiting the coverage volume.

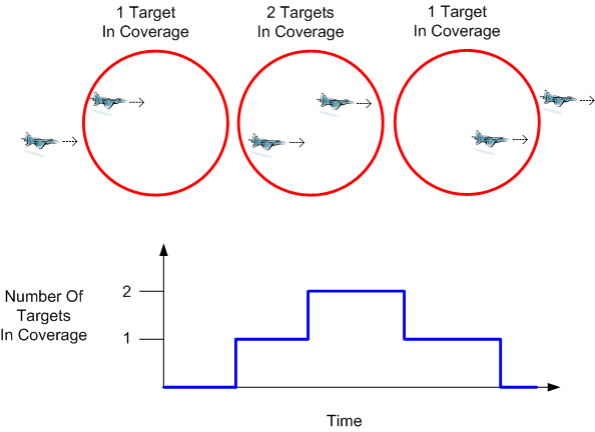

Assume that the surveillance volume is represented in software as a dynamically changing, in-memory database of target objects. On system startup, the database is initialized as empty. During operation, targets are inserted, updated, and deleted in response to changes that occur in the “real” world.

The figure below models each target’s behavior as a state transition diagram (STD). The point to note is that a target in a radar application is stateful and mutable. Regardless of what functional language purists say about statefulness and mutability being evil, they occur naturally in the radar application domain.

Note that the STD also indicates that the application domain requires garbage collection (GC) in the form of deallocation of target memory when a detection hasn’t been received within X seconds of the target’s prior update.

Since the system must operate in real-time to be useful, we’d prefer that the target memory be deleted as soon as the real target it represents exits the surveillance volume. We’d prefer the GC to be under the direct, local, control of the programmer and not according to the whims of an underlying, centralized, virtual machine whose GC kicks it whenever it feels like it.

With these domain-specific attributes in mind, C++ seems like the best programming language fit for real-time radar domain applications. The right tool for the job, no? If you disagree, please state your case.

The Biggest Cheerleader

Herb Sutter is by far the biggest cheerleader for the C++ programming language – even more so than the language’s soft spoken creator, Bjarne Stroustrup. Herb speaks with such enthusiasm and optimism that it’s infectious.

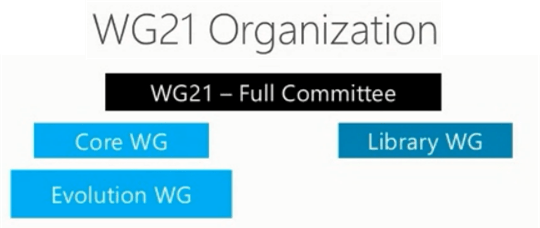

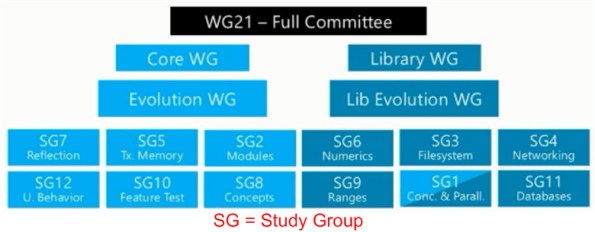

In his talk at the recently concluded GoingNative2013 C++ conference, Herb presented this slide to convey the structure of the ISO C++ Working Group 21 (WG21):

On the left, we have the language core and language evolution working groups. On the right, we have the standard library working group.

But wait! That was the organizational structure as of 18 months ago. As of now, we have this decomposition:

As you can see, there’s a lot of volunteer effort being applied to the evolution of the language – especially in the domain of libraries. In fact, most of the core language features on the left side exist to support the development of the upcoming libraries on the right.

In addition to the forthcoming minor 2014 release of C++, which adds a handful of new features and fixes some bugs/omissions from C++11, the next major release is slated for 2017. Of course, we won’t get all of the features and libraries enumerated on the slide, but the future looks bright for C++.

The biggest challenge for Herb et al will be to ensure the conceptual integrity of the language as a whole remains intact in spite of the ambitious growth plan. The faster the growth, the higher the chance of the wheels falling off the bus.

“The entire system also must have conceptual integrity, and that requires a system architect to design it all, from the top down.” – Fred Brooks

“Who advocates … for the product itself—its conceptual integrity, its efficiency, its economy, its robustness? Often, no one.” – Fred Brooks

I’m not a fan of committees in general, but in this specific case I’m confident that Herb, Bjarne, and their fellow WG21 friends can pull it off. I think they did a great job on C++11 and I think they’ll perform just as admirably in hatching future C++ releases.