Archive

The Drooping Progress Syndrome

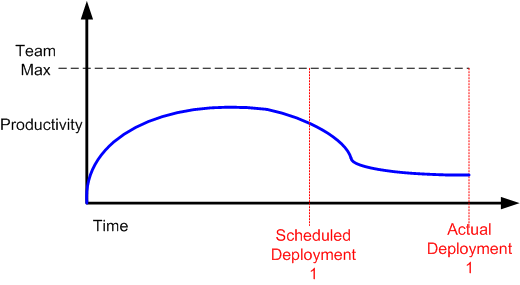

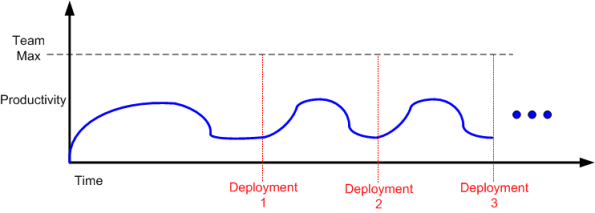

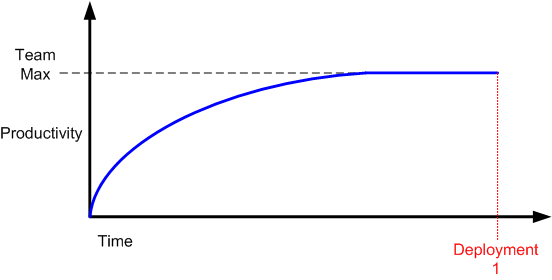

When a new product development project kicks off, nobody knows squat and there’s a lot of fumbling going on before real progress starts to accrue. As the hardware and software environment is stitched into place and initial requirements/designs get fleshed out, productivity slowly but surely rises. At some point, productivity (“velocity” in agile-ese) hits a maximum and then flattens into a zero slope, team-specific, cadence for the duration. Thus, one could be led to believe that a generic team productivity/progress curve would look something like this:

In “The Year Without Pants“, Scott Berkun destroys this illusion by articulating an astute, experiential, observation:

In “The Year Without Pants“, Scott Berkun destroys this illusion by articulating an astute, experiential, observation:

This means that at the end of any project, you’re left with a pile of things no one wants to do and are the hardest to do (or, worse, no one is quite sure how to do them). It should never be a surprise that progress seems to slow as the finish line approaches, even if everyone is working just as hard as they were before. – Scott Berkun

Scott may have forgotten one class of thing that BD00 has experienced over his long and un-illustrious career – things that need to get done but aren’t even in the work backlog when deployment time rolls in. You know, those tasks that suddenly “pop up” out of nowhere (BD00 inappropriately calls them “WTF!” tasks).

Nevertheless, a more realistic productivity curve most likely looks like this:

If you’re continuously flummoxed by delayed deployments, then you may have just discovered why.

Related articles

- The Year Without Pants: An interview with author Scott Berkun (oldienewbies.wordpress.com)

- Scott Berkun Shares Advice for Writers Working Remotely (mediabistro.com)

- A Book in 5 Minutes: “The Year without Pants: WordPress.com and the Future of Work” (tech.co)

A Concrete Agile Practices List

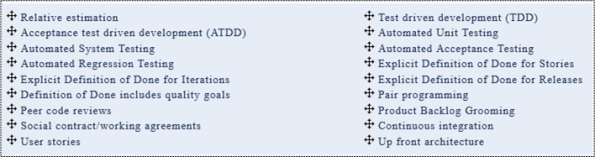

Finally, I found out what someone actually thinks “agile practices” are. In “What are the Most Important and Adoption-Ready Agile Practices?”, Shane-Hastie presents his list:

Kudos to Shane for putting his list out there.

Ya gotta love all the “explicit definition of done” entries (“Aren’t you freakin’ done yet?“). And WTF is “Up front architecture” doing on the list? Isn’t that a no-no in agile-land? Shouldn’t it be “emergent architecture“? And no kanban board entry? What about burn down charts?

Alas, I can’t bulldozify Shane’s list too much. After all, I haven’t exposed my own agile practices list for scrutiny. If I get the itch, maybe I’ll do so. What’s on your list?

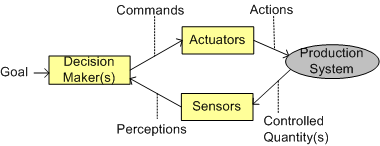

Unobservable, Uncontrollable

Piggybacking on yesterday’s BS post, let’s explore (and make stuff up about) a couple of important control system “ilities“: observability and controllability.

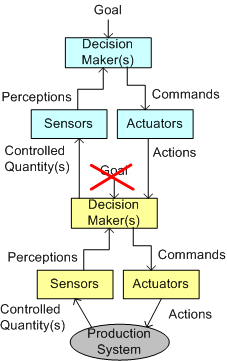

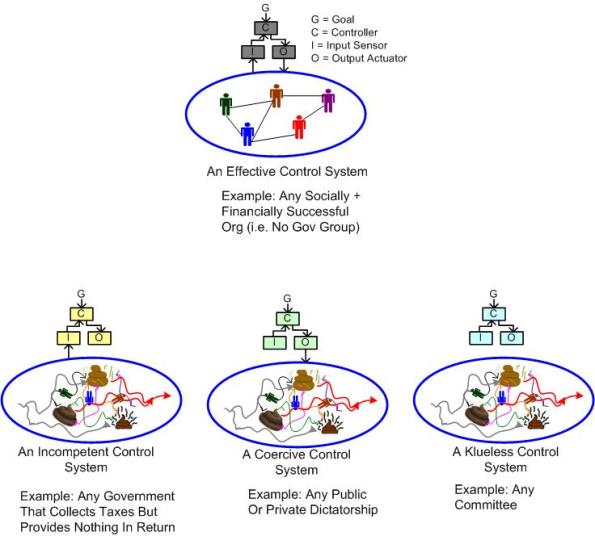

First, let’s look at a fully functional control system:

As long as the (commands -> actions -> CQs -> perceptions) loop of “consciousness” remains intact, the system’s decision maker(s) enjoy the luxury of being able to “control the means of production“. Whether this execution of control is effective or ineffective is in the eye of the beholder.

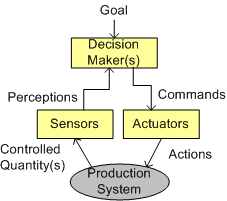

As the figure below illustrates, the capability of decision-makers to control and/or observe the functioning of the production system can be foiled by slicing through its loop of “consciousness” at numerous points in the system.

From the perspective of the production system, simply ignoring or misinterpreting the non-physical actions imposed on it by the actuators will severely degrade the decision maker’s ability to control the system. By withholding or distorting the state of the important “controlled quantities” crucial for effective decision making, the production system can thwart the ability of the decision maker(s) to observe and assess whether the goal is being sought after.

In systems where the functions of the components are performed by human beings, observability and controllability get compromised all the time. The level at which these “ilities” are purposefully degraded is closely related to how fair and just the decision makers are perceived to be in the minds of the system’s sensors, actuators, and (especially the) producers.

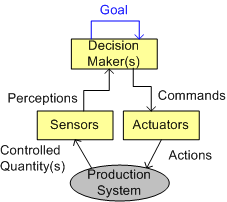

Who’s Controlling The Controller?

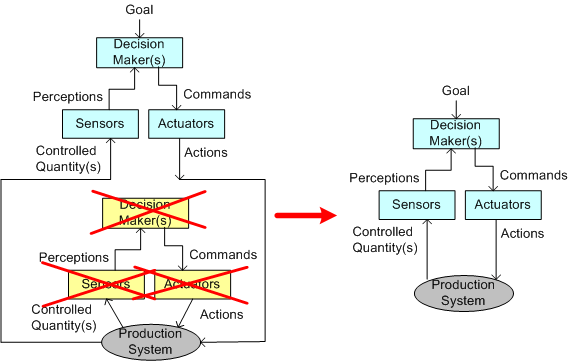

The figure below models a centralized control system in accordance with Bill Powers’ Perceptual Control Theory (PCT).

Given 1: a goal to achieve, and 2: the current perceived state of the production system, the decision-making apparatus issues commands it presumes will (in a timely fashion) narrow the gap between the desired goal and the current system state.

But wait! Where does the goal come from, or, in cybernetics lingo, “who’s controlling the controller?” After all, the entity’s perceptions, commands, actions, and controlled quantity signals all have identifiable sources in the model. Why doesn’t the goal have a source? Why is it left dangling in an otherwise complete model?

Abstraction is selective ignorance – Andrew Koenig

Well, as Bill Clinton would say, “it depends“. In the case of an isolated system (if there actually is such a thing), the goal source is the same as the goal target: the decision-maker itself. Ahhhh, such freedom.

On the other hand, if our little autonomous control system is embedded within a larger hierarchical control system, then the goal of the parent system decision maker takes precedence over the goal of the child decision maker. In the eyes of its parent, the child decision maker is the parent’s very own virtual production subsystem be-otch.

To the extent that the parent and child decision maker’s goals align, the “real” production system at the bottom of the hierarchy will attempt to achieve the goal set by the parent decision maker. If they are misaligned, then unless the parent interfaces some of its own actuator and sensor resources directly to the real production system, the production system will continue to do the child decision maker’s bidding. The other option the parent system has is to evict its child decision maker subsystem from the premises and take direct control of the production system. D’oh! I hate when that happens.

Effective, Incompetent, Coercive, Klueless

In any control system design, the accuracy of its input sensors, the force of its output actuators, the ability of its controllers to decide whether the system’s goals are being met, and the responsiveness (time lag) of all three of its parts determine its performance.

However, that’s not enough. All of the control system’s sensors and actuators must be actually interfaced to the controlled system in order for the controller + controllee supra-system to have any chance at meeting the goal supplied to (or by) the controller.

The Same Old Wine

Investment is to Goldman Sachs as management is to McKinsey & Co. These two prestigious institutions can do no wrong in the eyes of the rich and powerful. Elite investors and executives bow down and pay homage to Goldman McKinsey like indoctrinated North Koreans do to Kimbo Jongo Numero Uno.

As the following snippet from Art Kleiner’s “Who Really Matters” illustrates, McKinsey & Co, being chock full of MBAs from the most expensive and exclusionary business schools in the USA, is all about top-down management control systems:

…says McKinsey partner Richard Foster, author of Creative Destruction. If you ask companies how many control systems they have, they don’t know. If you ask them how much they’re spending on control, they say, ‘We don’t add it up like that.’ If you ask them to rank their control systems from most to least cost-effective, then cut out the twenty percent at the bottom, they can’t.” (And this from a partner at McKinsey, the firm whose advice has launched a thousand measurement and control systems.)

A dear reader recently clued BD00 into this papal release from a trio of McKinsey principals: “Enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of application development”. BD00 doesn’t know fer sure (when does he ever?), but he’ll speculate (when does he never?) that none of the authors has ever been within binoculars distance of a software development project.

Yet, they laughingly introduce a…

..viable means of measuring the output of application-development projects.

Their highly recommended application development control system is based on, drum roll please…. “Use Cases” (UC) and “Use Case Points” (UCP).

Knowing that their elite, money-hoarding, efficiency-obsessed, readers most probably have no freakin’ idea what a UC is, they painstakingly spend two paragraphs explaining the twenty year old concept (easily looked up on the web); concluding that…

..both business leaders and application developers find UCs easy to understand.

Well, yeah. Done “right“, UCs can be a boon to development – just like doing “agile” right. But how often have you ever seen these formal atrocities ever done right? Oh, I forgot. All that’s needed is “training” in how to write high quality UCs. Bingo, problem solved – except that training costs money.

Next up, the authors introduce their crown jewel output measurement metric, the “UCP“:

UCP calculations represent a count of the number of transactions performed by an application and the number of actors that interact with the application in question. UCPs, because they are simple to calculate, can also be easily rolled out across an organization.

So, how is an easily rolled out UCP substantively different than the other well known metric: the “Function Point” (FP)?

Another approach that’s often talked about for measuring output is Function Points. I have a little more sympathy for them, but am still unconvinced. This hasn’t been helped by stories I’ve heard of that talk about a single system getting counts that varied by a factor of three from different function point counters using the same system. – Martin Fowler

I guess that UCPs are superior to FPs because it is implied that given X human UCP calculators, they’ll all tally the same result. Uh, OK.

Not content to simply define and describe how to employ the winning UC + UCP metrics pair to increase productivity, the McKinseyians go on to provide one source of confirmation that their earth-shattering, dual-metric, control system works. Via an impressive looking chart with 12 project data points from that one single source (perhaps a good ole boy McKinsey alum?), they confidently proclaim:

Analysis therefore supports the conclusion that UCPs’ have predictive power.

Ooh, the words “analysis” and “predictive” and “power” all in one sentence. Simply brilliant; spoken directly in the language that their elite target audience drools over.

The article gets even more laughable (cry-able?) as the authors go on to describe the linear, step-by-step “transformation” process required to put the winning UC + UCP system in place and how to overcome the resistance “from below” that will inevitably arise from such a large-scale change effort. Easy as pie, no problemo. Just follow their instructions and call them for a $$$$$$ consultation when obstacles emerge.

So, can someone tell BD00 how the McKinsey UC + UCP dynamic duo is any different than the “shall” + Function Point duo? Does it sound like the same old wine in a less old bottle to you too?

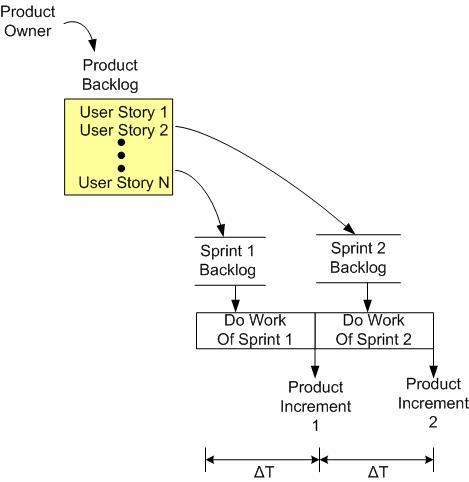

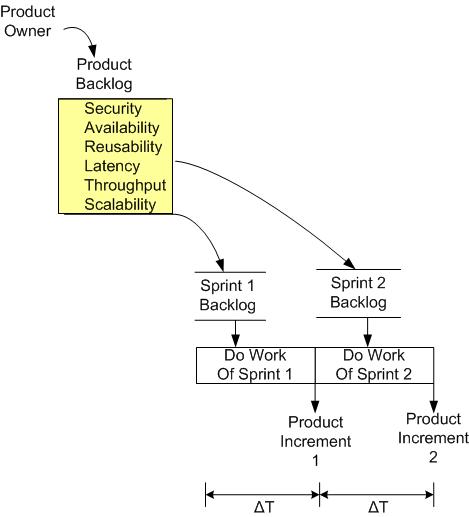

Scrummin’ For The Ilities

Whoo hoo! The product owner has funded our project and we’ve spring-loaded our backlog with user stories. We’re off struttin’ and scrummin’ our way to success:

But wait! Where are the “ilities” and the other non-functional product requirements? They’re not in your backlog?

Uh, we don’t do “ilities“. It’s not agile, it’s BDUF (Big Design Up Front). We no need no stinkin’ arkitects cuz we’re all arkitects. Don’t worry. These “ilities” thingies will gloriously emerge from the future as we implement our user stories and deliver working increments every two weeks – until they stop working.

Consumption AND Creation

Bill Gates is obviously biased, but Bob Lewis is not. What they have in common is the same contrarian opinion as BD00: Windows 8 is better than iOS and Android. OMG! WTF?

The iPad is better done. It’s more polished and has fewer irritations. None of this matters when the subject is getting work done. For that, Windows 8 is the superior tablet OS… When you have to get down to work, even with all the aggravations there’s really no contest. – Bob Lewis

But a lot of those (iOS and Android) users are frustrated, they can’t type, they can’t create documents. They don’t have Office there. So we’re providing them something with the benefits they’ve seen that have made that a big category, but without giving up what they expect in a PC. – Bill Gates

I know, I know. There are equivalents for Microsoft office on iOS and Android. But they don’t stack up very well against Microsoft’s well-integrated, flagship application suite. Android and iOS are touch-centric, which is a boon to consumption, but Win8 embraces touch, the keyboard, and the mouse all as first class citizens. Simply stated, iOS and Android are superior when it comes to consuming content, but Win8 is king at facilitating both consumption and creation.

I have a Kindle Fire HD and an iPhone 5, both of which I love for consumption of content. I don’t own a Win8 tablet or all-in-one PC yet, but being a somewhat creative blog writer and dorky graphics sketcher, I’m gonna get one or the other soon.

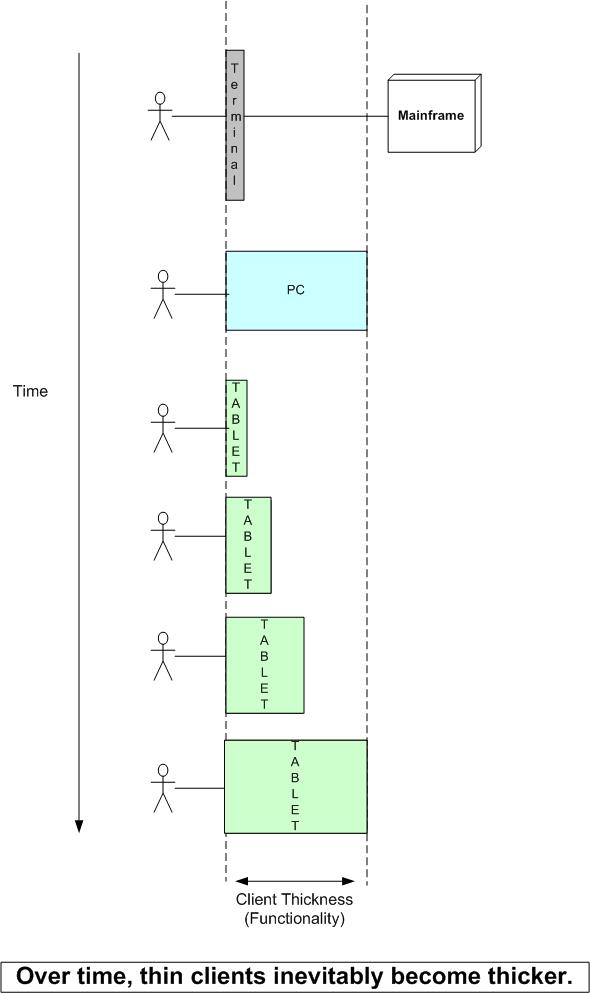

In addition to Mr. Lewis and Mr. Gates, Dr. Dobb’s editor Andrew Binstock equivalently states ( “The Ever-Fatter Thin Client”):

But the vision of a tablet cum keyboard as the new model of PC is right on. This is the fat client come to the new form factor. I believe the future is heading in that direction and that the Microsoft Surface leads the way. I’ve been using an Intel-based Surface Pro for several weeks now and very much like the combination of PC and tablet that it provides. The device, while considerably more expensive than the standard tablet, represents a believable next step for the industry — a full PC (with Intel processor, SSD disk, 4GB RAM, 1920×1080 screen) that can be used as a touch-enabled tablet. Only battery life and cost stand in the way of wide acceptance.

Lately, Microsoft’s financial performance has been deteriorating because of the rise of the thin tablet. However, like they always seem to do, I believe the company will recover and come to the forefront once again. The software “thickness” of Win8 and the hardware “thickness” of Intel’s CPUs will eventually win out in the long run because they facilitate both consumption and creation much better than the current bevy of alternatives.

Big, No, And Just Enough

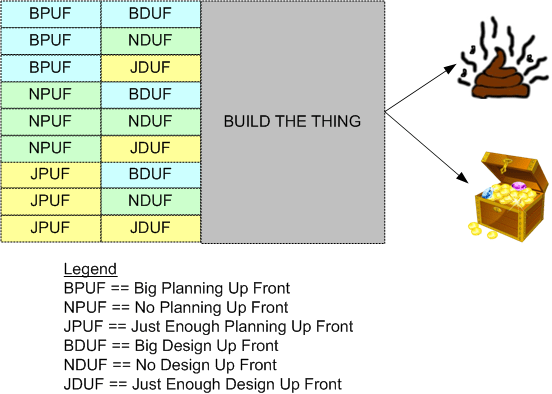

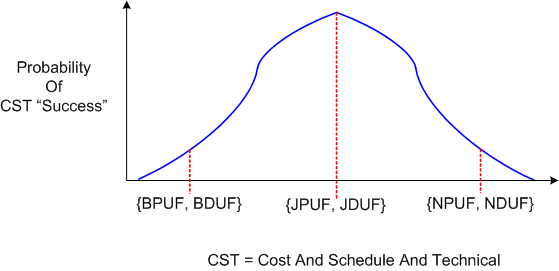

Assume (which is a bad thing to do) that you can characterize a project by three activities: Planning, Designing, and Building. Next, assume (which is still a bad thing to do) that the planning and designing activities can each be sub-characterized by “Big“, “No“, and “Just Enough“.

Forgetting about what “Just Enough” exactly means, check out this methodology-agnostic probability density function:

Do you think the curve is right? You better not. The sample size BD00 used to generate it is zero,

One Or Many

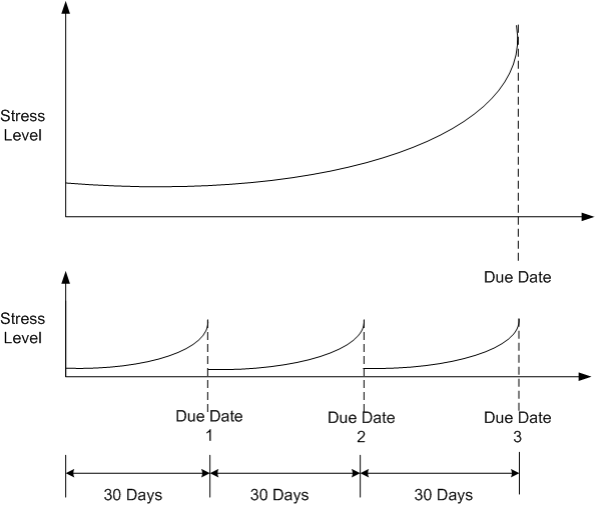

The figure below models the increase in team stress level versus time for waterfall and time-boxed projects. As a project nears a delivery date, the stress levels increase dramatically as the team fixes turds, integrates individually developed features into the whole, and takes care of the boring but important stuff that nobody wanted to do earlier.

One tradeoff between the two types of projects is maximum stress level vs. number of stressful events. The maximum level of experienced stress is much higher for waterfall than any one time-boxed sprint, but it only occurs once as opposed to monthly. Pick your poison: a quick death by guillotine or a slow death by a thousand cuts.

Agilistas would have everyone believe that time-boxed projects impose a constant but very low level of healthy stress on team members while waterfall quagmires impose heart-attack levels of stress on the team. They may be right, because…..

(In case you haven’t noticed, BD00 is feeling the need to use the Einstein pic above more and more in his posts. I wonder why that is.)