Archive

Cppcheck Test Run

Since I think that a static code analyzer can help me and my company produce higher quality code, I decided to download and test Cppcheck:

Cppcheck is an analysis tool for C/C++ code. Unlike C/C++ compilers and many other analysis tools, we don’t detect syntax errors. Cppcheck only detects the types of bugs that the compilers normally fail to detect. The goal is no false positives.

After the install, I ran Cppcheck on the root directory of a code base that contains over 200K lines of C++ code. As the figure below shows, 1077 style and error violations were flagged. The figure also shows a sample of the specific types of style and error violations that Cppcheck flagged within this particular code base.

After this test run, I ran Cppcheck on the five figure code base of the current project that I’m working on. Lo and behold, it didn’t flag any suspicious activity in my pristine code. Hah, hah, the last sentence was a joke! Cppcheck did flag some style warnings in my code, but (thankfully) it didn’t spew out any dreaded error warnings. And of course, I mopped up my turds.

Because of the painless install, its simplicity of use, and its speed of execution, I’ve added Cppcheck to my nerd toolbelt. I’m gonna run Cppcheck on every substantial piece of C++ code that I write in the future.

I want to sincerely thank all the programmers who contributed their free time to the Cppcheck project for the nice product they created and unselfishly donated to the world. You guys rock.

Call Tree

Check out the call thicket, oops, I mean call tree, below. From the root main() node, you can deduce that the 26 function program is written in C. Actually, there are several more than 26 functions because a few of the functions in the model call other lower level functions not shown in the figure.

Even though the functions are cloaked in a sequential numbering scheme, they’re not neatly called one right after another. Intertwined between, around, and across the function calls are a bunch of nested if-then and switch-case statements that make the mess more intimidating. Execution path sequencing is controlled by > 20 statically loaded configuration parameters and several dynamically computed control parameters.

I’ve got to transform this beast into an object oriented C++ design and verify that the new design works. Of course, there are no existing unit, integration, or system tests to reuse. Wish me luck!

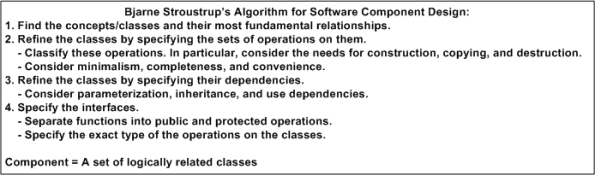

BS Design

Sorry, but I couldn’t resist naming the title of this post as it is written. However, despite what you may have thought on first glance, BS stands for dee man, Bjarne Stroustrup. In chapter 23 of “The C++ Programming Language“, Bjarne offers up this advice regarding the art of mid-level design:

To find out the details of executing each iterative step in the while(not_done){} loop, go buy the book. If C++ is your primary programming language and you don’t have the freakin’ book, then shame on you.

Bjarne makes a really good point when he states that his unit of composition is a “component”. He defines a component as a cluster of classes that are cohesively and logically related in some way.

A class should ideally map directly into a problem domain concept, and concepts (like people) rarely exist in isolation. Unless it’s a really low level concrete concept on the order of a built in type like “int”, a class will be an integral player in a mini system of dynamically collaborating concepts. Thinking myopically while designing and writing classes (in any language that directly supports object oriented design) can lead to big, piggy classes and unnecessary dependencies when other classes are conceived and added to the kludge under construction – sort of like managers designing an org to serve themselves instead of the greater community. 🙂

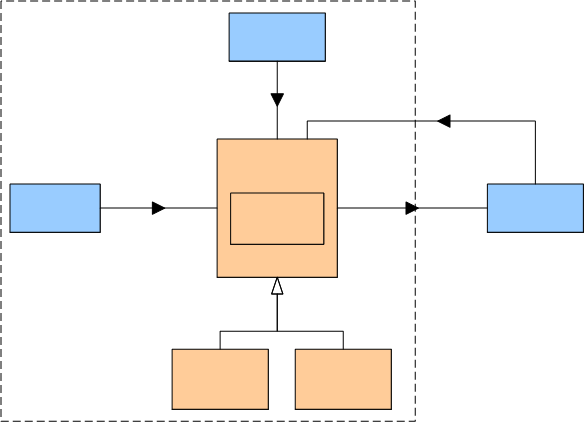

The figure below shows “revision 0” of a mini system of abstract classes that I’m designing and writing on my current project. The names of the classes have been elided so that I don’t get fired for publicly disclosing company secrets. I’ve been architecting and designing software like this from the time I finally made the painful but worthwhile switchover to C++ from C.

The class diagram is the result of “unconsciously” applying step one of Bjarne’s component design process. When I read Bjarne’s sage advice it immediately struck a chord within me because I’ve been operating this way for years without having been privy to his wisdom. That’s why I wrote this blowst – to share my joy at discovering that I may actually be doing something right for a change.

Another Humbler

It’s often frustrating but always well worth the pain to get humbled from time to time. If it happens often enough, it’ll deflate your head somewhat and keep you on the ground with the rest of your plebe peers. Too much humbling and you lose your self-esteem, too little humbling and you morph into an insufferable, self-important narcissist – like me. One of the reasons why I love zappos.com is that one of their core company values is “Be Humble”.

The other day, I was slinging some code and I was hunting for a bug. In order to slow things down and help expose the critter, I inserted the following code into my program:

//sleep for a second to allow already waiting subscribers a chance to discover us

boost::this_thread::sleep(boost::posix_time::milliseconds(2000));

std::cerr << “\nSleeping For A Bit….. Zzzz\n\n”;

I then ran the sucker and watched the console intently. Low and behold, the program did not seem to pause for the 2 seconds that I commanded. WTF? After the “Sleeping For A Bit” message was printed to the console, the program just zoomed along. WTF? Over the next 10 minutes, I reran the code several times and stared at the source. WTF? Then, by the grace of the universe, it hit me out of the blue:

//sleep for a second to allow already waiting subscribers a chance to discover us

std::cerr << “\nSleeping For A Bit….. Zzzz\n\n”;

boost::this_thread::sleep(boost::posix_time::milliseconds(2000));

Duh! This never happens to you, right?

Now, if I can only practice what I preach; walk the talk.

C++ Naming Conventions

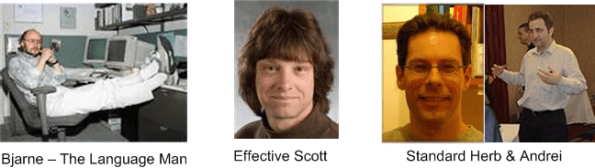

For grins, I perused a few books written by several C++ mentors that I respect and admire. I was interested in the naming conventions that they personally use when writing code. Here are the results.

Scott Meyers (Effective C++):

class names – class PhoneBook {};

member function names – void addPhoneNumber(const std::string& pn);

member attribute names – std::string theAddress;

Note: no annotation to distinguish class member attributes from local function variables.

Bjarne Stroustrup (The C++ Programming Language):

“I consider the CamelCodingStyle of identifiers “pug ugly” and strongly prefer underscore_style as cleaner and inherently more readable, and many people agree. On the other hand, many reasonable people disagree.“

class names – class Phone_book {};

member function names – void add_phone_number(const std::string& pn);

member attribute names – std::string the_address;

Note: no annotation to distinguish class member attributes from local function variables.

Herb Sutter and Andrei Alexandrescu (C++ Coding Standards):

class names – class PhoneBook {};

member function names – void AddPhoneNumber(const std::string& pn);

member attribute names – std::string theAddress_;

Note: they use post-underscores to distinguish class member attributes from local function variables (int clientName_; //is a class member)

When I’m not constrained by a specific naming standard, I use this one:

class names – class PhoneBook {};

member function names – void add_phone_number(const std::string& pn);

member attribute names – std::string the_address_;

Note: Like Herb & Andrei, I use post-underscores to distinguish class member attributes from local function variables (int client_name_; //is a class member).

Close Spatial Proximity

Even on software development projects with agreed-to coding rules, it’s hard to (and often painful to all parties) “enforce” the rules. This is especially true if the rules cover superficial items like indenting, brace alignment, comment frequency/formatting, variable/method name letter capitalization/underscoring. IMHO, programmers are smart enough to not get obstructed from doing their jobs when trivial, finely grained rules like those are violated. It (rightly) pisses them off if they are forced to waste time on minutiae dictated by software “leads” that don’t write any code and (especially) former programmers who’ve been promoted to bureaucratic stooges.

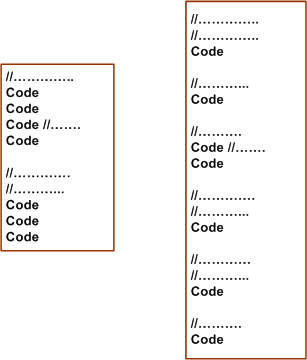

Take the example below. The segment on the right reflects (almost) correct conformance to the commenting rule “every line in a class declaration shall be prefaced with one or more comment lines”. A stricter version of the rule may be “every line in a class declaration shall be prefaced with one or more Doxygenated comment lines”.

Obviously, the code on the left violates the example commenting rule – but is it less understandable and maintainable than the code on the right? The result of diligently applying the “rule” can be interpreted as fragmenting/dispersing the code and rendering it less understandable than the sparser commented code on the left. Personally, I like to see necessarily cohesive code lines in close spatial proximity to each other. It’s simply easier for me to understand the local picture and the essence of what makes the code cohesive.

Even if you insert an automated tool into your process that explicitly nags about coding rule violations, forcing a programmer to conform to standards that he/she thinks are a waste of time can cause the counterproductive results of subversive, passive-aggressive behavior to appear in other, more important, areas of the project. So, if you’re a software lead crafting some coding rules to dump on your “team”, beware of the level of granularity that you specify your coding rules. Better yet, don’t call them rules. Call them guidelines to show that you respect and trust your team mates.

If you’re a software lead that doesn’t write code anymore because it’s “beneath” you or a bureaucrat who doesn’t write code but who does write corpo level coding rules, this post probably went right over your head.

Note: For an example of a minimal set of C++ coding guidelines (except in rare cases, I don’t like to use the word “rule”) that I personally try to stick to, check this post out: project-specific coding guidelines.

Strongly Typed

In “Hackers and Painters“, one of my favorite essayists and modern day renaissance men, Paul Graham, states his disdain for strongly typed programming languages. The main reason is that he doesn’t like to be scolded by mindless compilers that handcuff his creativity by enforcing static type-checking rules. Being a C++ programmer, even though I love Paul and understand his point of view, I have to disagree. One of the reasons I like working in C++ is because of the language’s strong type checking rules, which are enforced on the source code during compilation. C++ compilers find and flag a lot of my programming mistakes prior to runtime <- where finding sources of error can be much more time consuming and frustrating.

Driven by “a fierce determination not to impose a specific one size fits all programming style” on programmers, Bjarne Stroustrup designed C++ to allow programmers to override the built-in type system if they consciously want to do so. By preserving the old C style casting syntax and introducing new, ugly C++ casting keywords (static_cast, dynamic_cast, etc) that purposefully make manual casts stick out like a sore thumb and easily findable in the code base, a programmer can legally subvert the type system.

C++ gets trashed a lot by other programming language zealots because it’s a powerful tool with a rich set of features and it supports multiple programming styles (procedural, abstract data types, object-oriented, generic) instead of just one “pure” style. Those attributes, along with Bjarne’s empathy with the common programmer, are exactly why I love using C++. How about you, what language(s) do and don’t you like? Why?

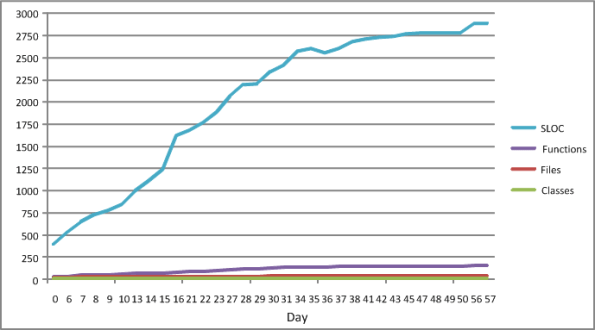

My Velocity

The figure below shows some source code level metrics that I collected on my last C++ programming project. I only collected them because the process was low ceremony, simple, and unobtrusive. I ran the source code tree through an easy to use metrics tool on a daily basis. The plots in the figure show the sequential growth in:

- The number of Source Lines Of Code (SLOC)

- The number of classes

- The number of class methods (functions)

- The number of source code files

So Whoopee. I kept track of metrics during the 60 day construction phase of this project. The question is: “How can a graph like this help me improve my personal software development process?”.

The slope of the SLOC curve, which measured my velocity throughout the duration, doesn’t tell me anything my intution can’t deduce. For the first 30 days, my velocity was relatively constant as I coded, unit tested, and integrated my way toward the finished program. Whoopee. During the last 30 days, my velocity essentially went to zero as I ran end-to-end system tests (which were designed and documented before the construction phase, BTW) and refactored my way to the end game. Whoopee. Did I need a plot to tell me this?

I’ll assert that the pattern in the plot will be unspectacularly similar for each project I undertake in the future. Depending on the nature/complexity/size of the application functionality that will need to be implemented, only the “tilt” and the time length will be different. Nevertheless, I can foresee a historical collection of these graphs being used to predict better future cost estimates, but not being used much to help me improve my personal “process”.

What’s not represented in the graph is a metric that captures the first 60 days of problem analysis and high level design effort that I did during the front end. OMG! Did I use the dreaded waterfall methodology? Shame on me.