Archive

Push And Pull Message Retrieval

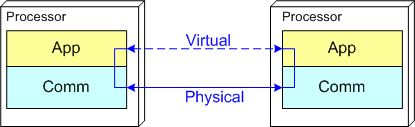

The figure below models a two layer distributed system. Information is exchanged between application components residing on different processor nodes via a cleanly separated, underlying communication “layer“. App-to-App communication takes place “virtually“, with the arcane, physical, over-the-wire, details being handled under the covers by the unheralded Comm layer.

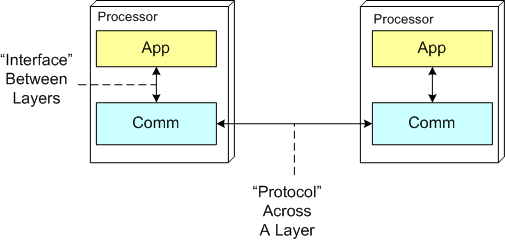

In the ISO OSI reference model for inter-machine communication, the vertical linkage between two layers in a software stack is referred to as an “interface” and the horizontal linkage between two instances of a layer running on different machines is called a “protocol“. This interface/protocol distinction is important because solving flow-control and error-control issues between machines is much more involved than handling them within the sheltered confines of a single machine.

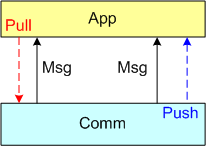

In this post, I’m going to focus on the receiving end of a peer-to-peer information transfer. Specifically, I’m going to explore the two methods in which an App component can retrieve messages from the comm layer: Pull and Push. In the “Pull” approach, message transfer from the Comm layer to the App layer is initiated and controlled by the App component via polling. In the “Push” method, inversion of control is employed and the Comm layer initiates/controls the transfer by invoking a callback function installed by the App component on initialization. Any professional Comm subsystem worth its salt will make both methods of retrieval available to App component developers.

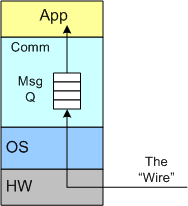

The figure below shows a model of a comm subsystem that supplies a message queue between the application layer and the “wire“. The purpose of this queue is to prevent high rate, bursty, asynchronous message senders from temporarily overwhelming slow receivers. By serving as a flow rate smoother, the queue gives a receiver App component a finite amount of time to “catch up” with bursts of messages. Without this temporary holding tank, or if the queue is not deep enough to accommodate the worst case burst size, some messages will be “dropped on the floor“. Of course, if the average send rate is greater than the average processing rate in the receiving App, messages will be consistently lost when the queue eventually overflows from the rate mismatch – bummer.

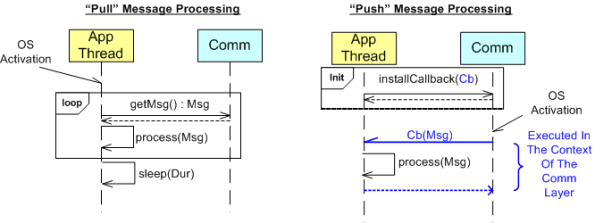

The UML sequence diagram below zeroes in on the interactions between an App component thread of execution and the Comm layer for both the “Push” and “Pull” methods of message retrieval. When the “Pull” approach is implemented, the OS periodically activates the App thread. On each activation, the App sucks the Comm layer queue dry; performing application-specific processing on each message as it is pulled out of the Comm layer. A nice feature of the “Pull” method, which the “Push” method doesn’t provide, is that the polling rate can be tuned via the sleep “Dur(ation)” parameter. For low data rate message streams, “Dur” can be set to a long time between polls so that the CPU can be voluntarily yielded for other processing tasks. Of course, the trade-off for long poll times is increased latency – the time from when a message becomes available within the Comm layer to the time it is actually pulled into the App layer.

In the”Push” method of message retrieval, during runtime the Comm layer activates the App thread by invoking the previously installed App callback function, Cb(Msg), for each newly received message. Since the App’s process(Msg) method executes in the context of a Comm layer thread, it can bog down the comm subsystem and cause it to miss high rate messages coming in over the wire if it takes too long to execute. On the other hand, the “Push” method can be more responsive (lower latency) than the “Pull” method if the polling “Dur” is set to a long time between polls.

So, which method is “better“? Of course, it depends on what the Application is required to do, but I lean toward the “Pull” Method in high rate streaming sensor applications for these reasons:

- In applications like sensor stream processing that require a lot of number crunching and/or data associations to be performed on each incoming message, the fact that the App-specific processing logic is performed within the context of the App thread in the “Pull” method (instead of the Comm layer) means that the Comm layer performance is not dependent on the App-specific performance. The layers are more loosely coupled.

- The “Pull” approach is simpler to code up.

- The “Pull” approach is tunable via the sleep “Dur” parameter.

How about you? Which do you prefer, and why?

Flouting Convention

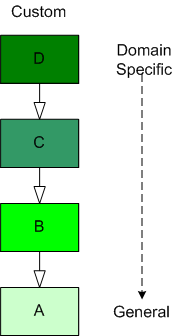

As software-centric systems get more complex, one of the most effective tools for preventing the creation of monstrous BBoMs downstream is “layering”. The figure below shows a generic model of the layering concept.

When you use layering, you partition your system into a vertical stack with the most “exciting” application-specific functions and objects at the top of the stack and the more mundane and boring functionality down in the basement. In a pure layered system, the higher layers depend on the services provided by the lower levels and there are no dependencies the other way. The cleaner and crisper your inter-layer boundaries, the lower your maintenance cost and frustration.

The figure below shows the conventional approach of representing an inheritance hierarchy in an object oriented design. What’s wrong with this picture? Relative to the layered model, it’s “upside down“. The most general class is on top and the most domain-specific class is at the bottom. WTF and D’oh!

Since “layering” has been around much longer than object-orientation, Bulldozer00 thinks that a layered, object-oriented software system should always be presented to stakeholders like this:

This method of representation aligns cleanly with the layered “view” of the system and is thus, less confusing and dis-orienting to all audiences, dontcha think? To hell with convention, – at least in this situation.

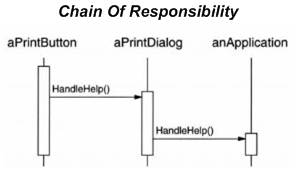

Chain Of Responsibility

One of the well known design patterns in the object-oriented software world is named “Chain Of Responsibility“. The UML sequence diagram below shows an example of how the software objects in the pattern collaborate with each other in order to ensure that a user initiated help request is handled somewhere in the GUI of an application.

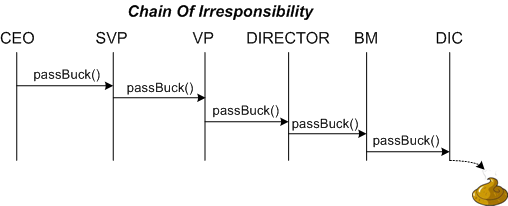

As you might surmise, the world of hierarchical superiority has an analogous pattern, err anti-pattern, named “Chain Of Irresponsibility“. Do ya think I need to add words to explain the inter-object collaborations for this pattern as shown in the UML sequence diagram that follows?

As you might surmise, the world of hierarchical superiority has an analogous pattern, err anti-pattern, named “Chain Of Irresponsibility“. Do ya think I need to add words to explain the inter-object collaborations for this pattern as shown in the UML sequence diagram that follows?

In case you were wondering, S = Senior, BM = Bozo Manager, and DIC = Dweeb In the Cellar.

Recursive Interpretation

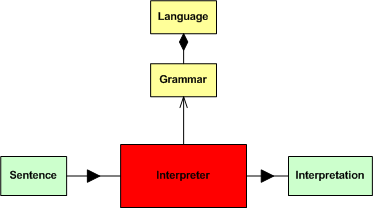

In their classic book, Design Patterns, the GoF defines the intent of the Interpreter pattern as:

Given a language, define a representation for its grammar along with an interpreter that uses the representation to interpret sentences in the language.

For your viewing pleasure, and because it’s what I like to do, I’ve translated (hopefully successfully) the wise words above into the SysML block diagram below.

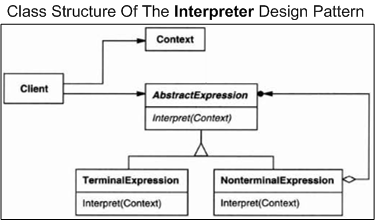

Moving on, observe the copied-and-pasted pseudo-UML class diagram of the GoF Interpreter design pattern below. In a nutshell, the “client” object builds and initializes the context of the sentence to be interpreted and invokes the interpret() operation – passing a reference to the context (in the form of a syntax tree) down into the concrete “xxxExpression” interpreter objects in a recursive descent so that they can do their piece of the interpretation work and then propagate the results back up the stack.

In their writeup of the Interpreter design pattern, the GoF state:

Terminal nodes generally don’t store information about their position in the abstract syntax tree. Parent nodes pass them whatever context they need during interpretation. Hence there is a distinction between shared (intrinsic) state and passed-in (extrinsic) state.

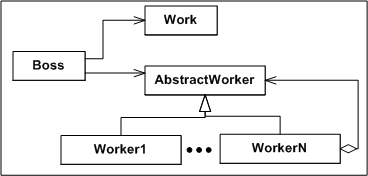

Since the classes in the Interpreter design pattern aren’t thinking, feeling, scheming humans concerned about status and looking good, the collection of collaborating classes do their jobs effectively and efficiently, just like mindless machines should. However, if you try to implement the Interpreter pattern on a project team with human “objects”, fuggedabout it. To start with, the “client” object (i.e. the boss) at the top of the recursion sequence won’t know how to create a coherent sentence or context. Even if the boss does do it, he/she may intentionally or unitentionally withhold the context from the recursion chain and invoke the interpret() operation of the first “XXXExpression” object (i.e. worker) with garbage. When the final interpretation of the garbled sentence is returned to the boss, it’s a new form of useless garbage.

On it’s way down the stack, at any step in the recursive descent, the propagated context can be distorted or trashed on purpose by self-serving intermediate managers and workers. Unlike a software system composed of mindless objects working in lock-step to solve a problem, the chances that the work will be done right, or even defined right, is miniscule in a DYSCO.

The Curiously Recurring Scramble Pattern

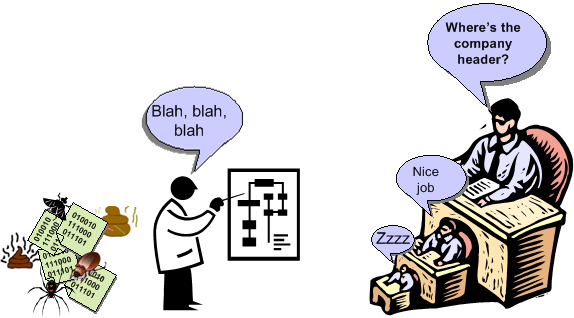

It’s funny to watch software development teams hack away for months building a just barely working patch-quilt monster that they can hardly understand themselves – and then scramble at the last minute generating design documents for some big upcoming management design review or “independent” auditor dog and pony show (woof woof!).

In this Curiously Recurring Scramble Pattern (CRSP), a successful attempt to avoid the labor of thinking is made as developers frantically sprinkle Doxygen annotations throughout the code and/or load the beast into a reverse engineering tool that mechanistically generates UML diagrams to model the as-built mess. It goes without saying that the tool’s “verbose” mode is selected in order to obscure meaning and promote the illusion of high falutin’ sophistication. Of course, all of this is a waste of time (= $$$$) because the dudes doing the reviewing (self-important managers and bureaucratic auditors) don’t want to understand a thing.

When the review or audit does take place; a couple of cream puff questions and comments are bantered about, check boxes are ticked off, a couple of superficial “action items” are generated, and the whole lovefest is rubber-stamped as a great success. Whoo Hoo, we rock!

Without a doubt, you and I have never been culturally forced to participate in an instantiation of the CRSP. We are above that nonsense, right? We do something like this.

“A meeting is a refuge from the dreariness of labor and the loneliness of thought.” – Bernard Baruch

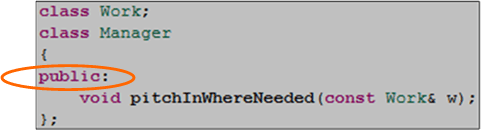

void Manager::pitchInWhereNeeded(const Work& w){}

Unless you’re a C++ programmer, you probably won’t understand the title of this post. It’s the definition of the “pitchInWhereNeeded” member function of a “Manager” class. If you look around your immediate vicinity with open eyes, that member function is most likely missing from your Manager class definition. If you’re a programmer, oops, I mean a software engineer, it’s probably also missing from your derived “SoftwareLead“, “SoftwareProjectManager“, and “SoftwareArchitect” classes too.

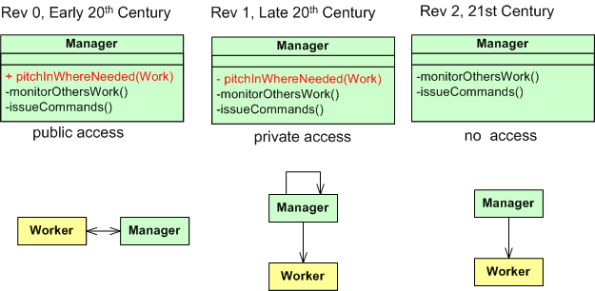

As the UML-annotated figure below shows, in the early twentieth century the “pitchInWhereNeeded” function was present and publicly accessible by other org objects. On revision number 1 of the “system”, as signaled by the change from “+” to “-“, its access type was changed to private. This seemingly minor change broke all existing “system” code and required all former users of the class to redesign and retest their code. D’oh!

On the second revision of the Manager class, this critical, system-trust-building member function mysteriously disappeared completely. WTF?. This rev 2 version of the code didn’t break the system, but the system’s responsiveness decreased since private self -calls by manager objects to the “pitchInWhereNeeded” function were deleted and more work was pushed back into the “other” system objects. Bummer.

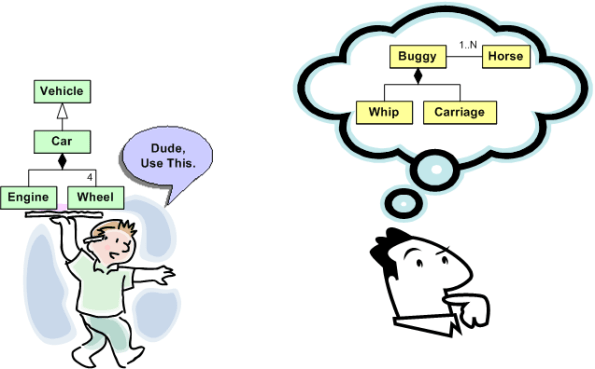

Reinventing The Wheel

In Federico Biancuzzi’s “Masterminds Of Programming“, UML co-creator Jim Rumbaugh states:

The computing field has a lot of people that think very well of themselves and seem to forget that there is any past to build upon. A lot of people keep reinventing things that have already been discovered. – Jim Rumbaugh

LOL! I understand what Jim’s saying, but there can be another reason for reinventing the wheel too. How many slightly different API versions of virtually similar “reusable” libraries are littered around your software development org? How many of them have you written and rewritten yourself?

If a library/module/component is poorly or “un” documented in terms of its design, external dependencies, and most importantly, usage examples, it t’aint gonna be reused. Even if the thang IS miraculously well documented, if the info is not integrated, organized, and easily accessible, it ain’t gonna be reused either. Both of these shortcomings, which are highly likely since most programmers don’t “do documentation” and managers don’t want to pay for non-camouflage documentation, guarantee reinventing the wheel over and over again.

Assume that you truly do want to reuse someone else’s code to save time, but all you have is the source code. You’re gonna have to pour through the mess to figure out what it offers, how it works, and what other components and libraries it depends on before you can consider using it “as is“. The larger and denser the component, the deeper and wider the inheritance tree, the more external dependencies, the more frustrated you’ll become and the less likely you’ll apply your brainpower and time to the task at hand. When that happens, Ta Dah, it’s time to roll your own – yet again. Hell, if you don’t document your own stuff, you might not even be able to eat your own dog food downstream. D’oh! I hate when that happens. And yes, it happens to me.

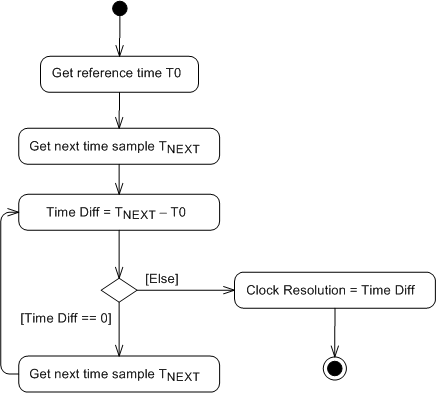

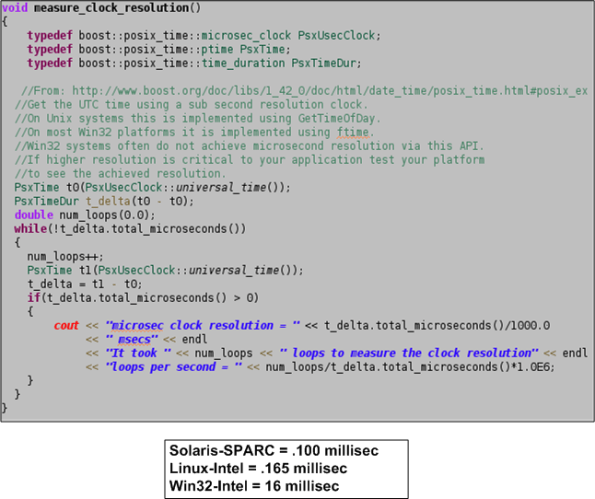

Measuring Clock Resolution

The Boost.Date_Time C++ library provides an excellent, platform-independent set of interrelated classes for measuring and tracking times and dates during program operation. It is much more capable and, more importantly, accurate than the standard C++ <ctime> library inherited from C. Since we need to benchmark the average and peak latency for our growing distributed, real-time, system infrastructure running on Linux, Solaris and (maybe) Win32 platforms, I decided to use the Boost.Date_Time functionality to measure the clock resolution on a representative of each platform.

The UML activity diagram below shows the simple algorithm that I used to write a small program that estimates the clock resolution of any compiler-CPU-OS platform combo that Boost.Date_Time is available for. The assumption underlying the design is that the program instructions inside the loop execute an order of magnitude faster than a clock tick increments. At CPU speeds on the order of GHz ( nanoseconds) and clock periods of microseconds, this is a pretty decent assumption, no? The algorithm simply spins around in a tight, high speed loop waiting for the clock to change value relative to an initial reference sample. Note that measuring hardware clock accuracy is another story (Does anyone know if clock hardware accuracy can even be estimated in software?).

The function below shows the super secret, proprietary, source code that uses the Boost.Date_Time facilities to implement the clock resolution estimation algorithm. Note that the boost microseconds clock, as opposed to the nanoseconds or seconds clock, is used to grab time samples. The seconds clock is too coarse grained for our needs and typical off-the-shelf servers do not provide hardware clocks with nanosecond resolutions without add on circuitry. The box below the code shows the results that I obtained for three platforms on which I ran the program. Of course, the results aren’t perfect (are any results ever perfect?), but since the Solaris and Linux results provide sub-millisecond resolution and we expect end-to-end system latencies on the order of hundreds of milliseconds, the clocks will satisfy our latency measurement needs. Of course, the Win32 result is crappy. Got any thoughts?

OMG! Design By Committee

In Federico Biancuzzi’s terrific “Masterminds Of Programming“, Federico interviews the three Amigo co-creators of UML. In discussing the “advancement” of the UML after the Amigos freely donated their work to the OMG for further development, Jim Rumbaugh had this to say:

The OMG (Object Management Group) is a case study in how political meddling can damage any good idea. The first version of UML was simple enough, because people didn’t have time to add a lot of clutter. Its main fault was an inconsistent viewpoint—some things were pretty high-level and others were closely aligned to particular programming languages. That’s what the second version should have cleared up. Unfortunately, a lot of people who were jealous of our initial success got involved in the second version. – Jim Rumbaugh

LOL! Following up, Jim landed a second blow:

The OMG process allowed all kinds of special interests to stuff things into UML 2.0, and since the process is mainly based on consensus, it is almost impossible to kill bad ideas. So UML 2.0 became a bloated monstrosity, with far too much dubious content, and still no consistent viewpoint and no way to define one. – Jim Rumbaugh

Double LOL!

Another UML co-creator, Grady Booch, says essentially the same thing but without specifically mentioning the OMG cabal:

UML 2.0 to some degree, and I’ll say this a little bit harshly, suffered a bit of a second system effect in that there were great opportunities and special interest groups, if you will, clamoring for certain specific features which added to the bloat of UML 2.0. – Grady Booch

Triple LOL!

Mitchi Henning, a key player during the CORBA era, rants about the OMG in this controversial “The Rise And Fall Of CORBA” article. Mitchi enraged the corbaholic community by lambasting both CORBA and the dysfunctional OMG politburo that maintains it:

Over the span of a few years, CORBA moved from being a successful middleware that was hailed as the Internet’s next-generation e-commerce infrastructure to being an obscure niche technology that is all but forgotten. This rapid decline is surprising. How can a technology that was produced by the world’s largest software consortium fall from grace so quickly? Many of the reasons are technical: poor architecture, complex APIs, and lack of essential features all contributed to CORBA’s downfall. However, such technical shortcomings are a symptom rather than a cause. Ultimately, CORBA failed because its standardization process virtually guarantees poor technical quality. Seeing that other standards consortia use a process that is very similar, this does not bode well for the viability of other technologies produced in this fashion. – Mitchi Henning

Maybe the kings and queens of the OMG should add an exclamation point to the end of their acronym: OMG!

The reason the OMG! junta interests me is because I’ve been working hands-on with RTI‘s implementation of the OMG Data Distribution Service (DDS) standard to design and build the infrastructure for a distributed sensor data processing server that will be embedded in a safety-critical supersystem. At this point in time, since DDS was co-designed, tested, and fielded by two commercial companies and it wasn’t designed from scratch by a big OMG committee, I think it’s a terrific standard. Particularly, I think RTI’s version is spectacular relative to the other two implementations that I know about. I hope the OMG! doesn’t transform DDS into an abomination………

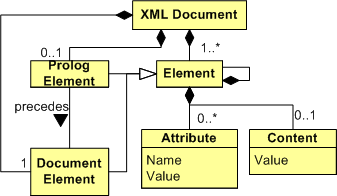

XML In UML

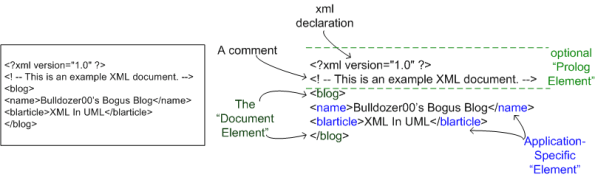

While learning XML, I concocted this UML class diagram of the conceptual structure of XML as a quick look refresher guide:

The diagram can be interpreted as:

- A typical XML document is composed of a “Document Element“, an optional “Prolog Element”, and many application specific “Element” classes.

- Besides a base “Element” class, there are two subclass types: the “Document Element” and the “Prolog Element”.

- In an XML file, the “Prolog Element” (if present) must precede the “Document Element”.

- An element contains content and, optionally, 1 or more “Attributes”.

- Each “Attribute” is comprised of a Name/Value pair.

- An element can also contain other nested elements, providing support for structured data representation.

Here’s a simple concrete example XML file and the mapping from concrete to abstract. Note that the “comment” and “xml declaration” lines aren’t represented in the abstract class diagram model. I left out that second order level of detail to keep the class diagram simple.