Archive

Hopping On The Anti-Fragile Bandwagon

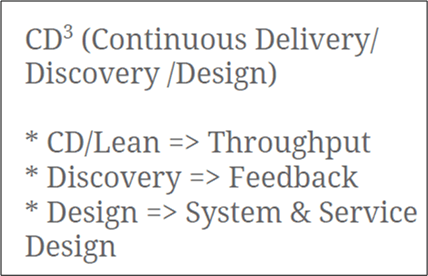

Since Martin Fowler works there, I thought ThoughtWorks Inc. must be great. However, after watching two of his fellow ThoughtWorkers give a talk titled “From Agility To Anti-Fragility“, I’m having second thoughts. The video was a relatively lame attempt to jam-fit Nassim Taleb’s authentic ideas on anti-fragility into the software development process. Expectedly, near the end of the talk the presenters introduced their “new” process for making your borg anti-fragile: “Continuous Delivery/Discovery/Design“. Lookie here, it even has a superscript in its title:

Having read Mr. Taleb’s four fascinating books, the one hour and twenty-six minute talk was essentially a synopsis of his latest book, “Anti-Fragile“. That was the good part. The ThoughtWorkers’ attempts to concoct techniques that supposedly add anti-fragility to the software development process introduced nothing new. They simply interlaced a few crummy slides with well-known agile practices (small teams, no specialists, short increments, co-located teams, etc) with the good slides explaining optionality, black/grey swans, convexity vs concavity, hormesis, and levels of randomness.

Warts And Barnacles

When I started this blog four years ago, I had to decide whether to publish as an anonymous coward or to use my real name. I struggled with the decision for a bit because I knew I was going to write frequently, real frequently, about dysfunctional management and institutional behaviors that I’ve both experienced and (even more so) read about over the years. In addition, since I’m a high energy, passionate animal who doesn’t hold much back and at times finds it hard to compromise, I knew that much of my content was going to be highly caustic and offensive.

Out of fear of repercussions, I decided to start writing incognito… until a dear friend brought up the perplexing issue again. After rethinking the situation, I resolved to let it all hang out. I gingerly hoisted my name up on my “About me” page.

Never say never, but I didn’t (and still don’t) care about climbing any corpo ladder or presenting the squeaky clean image that all main stream “leadership” books tout as necessary to “get ahead“. I have some hairy warts and barnacles growing on my brain and, hell, I choose to expose them.

So, if I don’t want to get ahead by movin’ on up, then WTF does BD00 want? I want to keep ruining drill bits while I blast away at the impenetrable bedrock that entombs the holy grail of effective software development. I like going deep, deep, deep down into the unexplored corners of programming (in C++, of course), design, architecture, requirements, and the squishy realm of team-based software development processes. These closely-coupled topics excite me because there seems to be no bottom, no final “truths“, no end to life-long learning in any of them. It’s what I was meant to do.

What were you meant to do?

Big Design, But Not All Upfront

When not ranting and raving on this blawg about “great injustices” (LOL) that I perceive are keeping the world from becoming a better place, I design, write, and test real-time radar system software for a living. I use the UML before, during, and after coding to capture, expose, and reason about my software designs. The UML artifacts I concoct serve as a high level coding road map for me; and a communication tool for subject matter experts (in my case, radar system engineers) who don’t know how to (or care to) read C++ code but are keenly interested in how I map their domain-specific requirements/designs into an implementable software design.

I’m not a UML language lawyer and I never intend to be one. Luckily, I’m not forced to use a formal UML-centric tool to generate/evolve my “bent” UML designs (see what I mean by “bent” UML here: Bend It Like Fowler). I simply use MSFT Visio to freely splat symbols and connections on an e-canvas in any way I see fit. Thus, I’m unencumbered by a nanny tool telling me I’m syntactically/semantically “wrong!” and rudely interrupting my thought flow every five minutes.

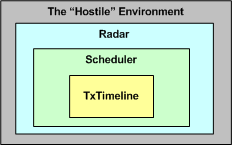

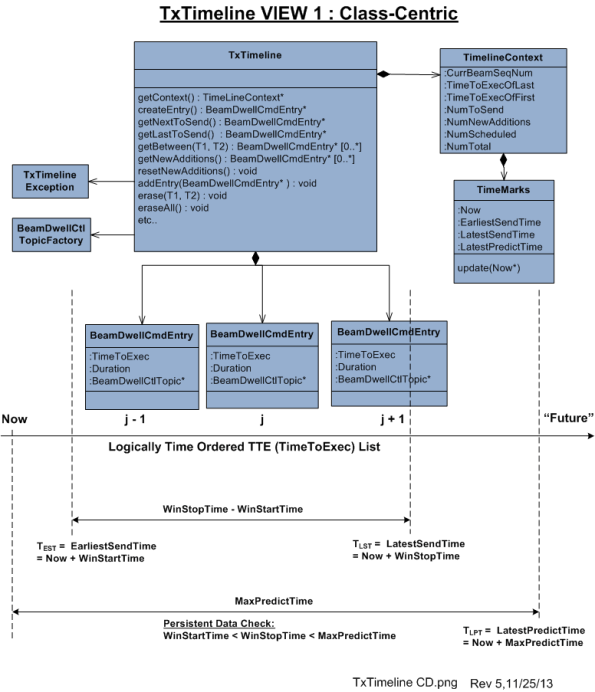

The 2nd graphic below illustrates an example of one of my typical class diagrams. It models a small, logically cohesive cluster of cooperating classes that represent the “transmit timeline” functionality embedded within a larger “scheduler” component. The scheduler component itself is embedded within yet another, larger scale component composed of a complex amalgam of cooperating hardware and software components; the radar itself.

When fully developed and tested, the radar will be fielded within a hostile environment where it will (hopefully) perform its noble mission of detecting and tracking aircraft in the midst of random noise, unwanted clutter reflections, cleverly uncooperative “enemy” pilots, and atmospheric attenuation/distortion. But I digress, so let me get back to the original intent of this post, which I think has something to do with how and why I use the UML.

The radar transmit timeline is where other necessarily closely coupled scheduler sub-components add/insert commands that tell the radar hardware what to do and when to do it; sometime in the future relative to “now“. As the radar rotates and fires its sophisticated, radio frequency pulse trains out into the ether looking for targets, the scheduler is always “thinking” a few steps ahead of where the antenna beam is currently pointing. The scheduler relentlessly fills the TxTimeline in real time with beam-specific commands. It issues those commands to the hardware early enough for the hardware to be able to queue, setup, and execute the minute transmit details when the antenna arrives at the desired command point. Geeze! I’m digressing yet again off the UML path, so lemme try once more to get back to what I originally wanted to ramble about.

Being an unapologetic UML bender, and not a fan of analysis-paralysis, I never attempt to meticulously show every class attribute, operation, or association on a design diagram. I weave in non-UML symbology as I see fit and I show only those elements I deem important for creating a shared understanding between myself and other interested parties. After all, some low level attributes/operations/classes/associations will “go away” as my learning unfolds and others will “emerge” during coding anyway, so why waste the time?

Notice the “revision number” in the lower right hand corner of the above class diagram. It hints that I continuously keep the diagram in sync with the code as I write it. In fact, I keep the applicable diagram(s) open right next to my code editor as I hack away. As a PAYGO practitioner, I bounce back and forth between code & UML artifacts whenever I want to.

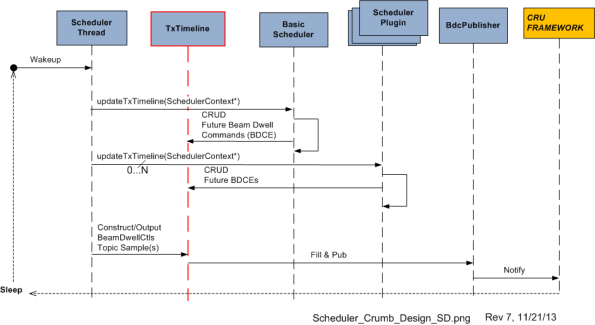

The UML sequence diagram below depicts a visualization of the participatory role of the TxTimeline object in a larger system context comprised of other peer objects within the scheduler. For fear of unethically disclosing intellectual property, I’m not gonna walk through a textual explanation of the operational behavior of the scheduler component as “a whole“. The purpose of presenting the sequence diagram is simply to show you a real case example that “one diagram is not enough” for me to capture the design of any software component containing a substantial amount of “essential complexity“. As a matter of fact, at this current moment in time, I have generated a set of 7+ leveled and balanced class/sequence/activity diagrams to steer my coding effort. I always start coding/testing with class skeletons and I iteratively add muscles/tendons/ligaments/organs to the Frankensteinian beast over time.

In this post, I opened up my trench coat and showed you my… attempted to share with you an intimate glimpse into the way I personally design & develop software. In my process, the design is not done “all upfront“, but a purely subjective mix of mostly high and low level details is indeed created upfront. I think of it as “Big Design, But Not All Upfront“.

Despite what some code-centric, design-agnostic, software development processes advocate, in my mind, it’s not just about the code. The code is simply the lowest level, most concrete, model of the solution. The practices of design generation/capture and code slinging/testing in my world are intimately and inextricably coupled. I’m not smart enough to go directly to code from a user story, a one-liner work backlog entry, a whiteboard doodle, or a set of casual, undocumented, face-to-face conversations. In my domain, real-time surveillance radar systems, expressing and capturing a fair amount of formal detail is (rightly) required up front. So, screw you to any and all NoUML, no-documentation, jihadists who happen to stumble upon this post. 🙂

The Next Big Four!

All Forked Up

I dunno who said it, but paraphrasing whoever did:

Science progresses as a succession of funerals.

Even though more accurate and realistic models that characterize the behavior of mass and energy are continuously being discovered, the only way the older physics models die out is when their adherents kick the bucket.

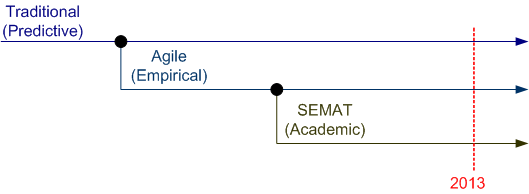

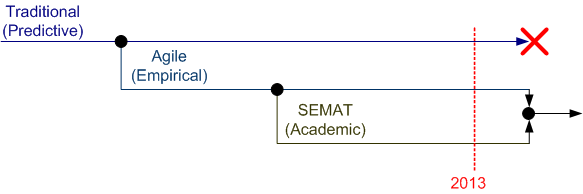

The same dictum holds true for software development methodologies. In the beginning, there was the Traditional (a.k.a waterfall) methodology and its formally codified variations (RUP, MIL-STD-498, CMMI-DEV, your org’s process, etc). Next, came the Agile fork as a revolutionary backlash against the inhumanity inherent to the traditional way of doing things.

The most recent fork in the methodology march is the cerebral SEMAT (Software Engineering Method And Theory) movement. SEMAT can be interpreted (perhaps wrongly) as a counter-revolution against the success of Agile by scorned, closet traditionalists looking to regain power from the agilistas.

On the other hand, perhaps the Agile and SEMAT camps will form an alliance and put the final nail in the coffin of the old traditional way of doing things before its adherents kick the bucket.

SEMAT co-creator Ivar Jacobson seems to think that hitching SEMAT to the Agile gravy train holds promise for better and faster software development techniques.

SEMAT co-creator Ivar Jacobson seems to think that hitching SEMAT to the Agile gravy train holds promise for better and faster software development techniques.

Who knows what the future holds? Is another, or should I say, “the next“, fork in the offing?

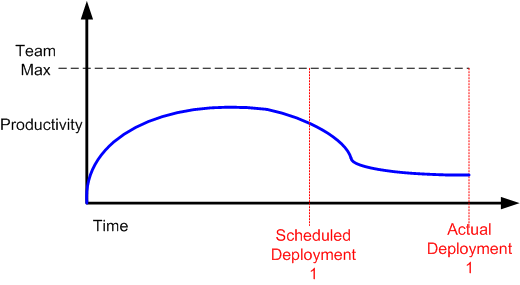

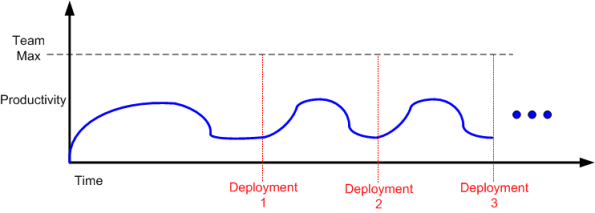

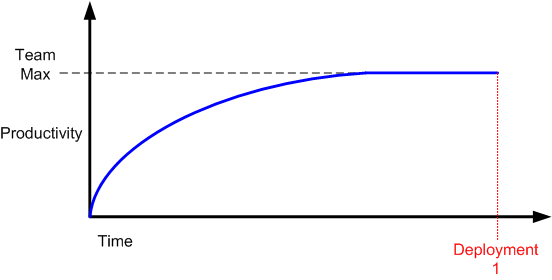

The Drooping Progress Syndrome

When a new product development project kicks off, nobody knows squat and there’s a lot of fumbling going on before real progress starts to accrue. As the hardware and software environment is stitched into place and initial requirements/designs get fleshed out, productivity slowly but surely rises. At some point, productivity (“velocity” in agile-ese) hits a maximum and then flattens into a zero slope, team-specific, cadence for the duration. Thus, one could be led to believe that a generic team productivity/progress curve would look something like this:

In “The Year Without Pants“, Scott Berkun destroys this illusion by articulating an astute, experiential, observation:

In “The Year Without Pants“, Scott Berkun destroys this illusion by articulating an astute, experiential, observation:

This means that at the end of any project, you’re left with a pile of things no one wants to do and are the hardest to do (or, worse, no one is quite sure how to do them). It should never be a surprise that progress seems to slow as the finish line approaches, even if everyone is working just as hard as they were before. – Scott Berkun

Scott may have forgotten one class of thing that BD00 has experienced over his long and un-illustrious career – things that need to get done but aren’t even in the work backlog when deployment time rolls in. You know, those tasks that suddenly “pop up” out of nowhere (BD00 inappropriately calls them “WTF!” tasks).

Nevertheless, a more realistic productivity curve most likely looks like this:

If you’re continuously flummoxed by delayed deployments, then you may have just discovered why.

Related articles

- The Year Without Pants: An interview with author Scott Berkun (oldienewbies.wordpress.com)

- Scott Berkun Shares Advice for Writers Working Remotely (mediabistro.com)

- A Book in 5 Minutes: “The Year without Pants: WordPress.com and the Future of Work” (tech.co)

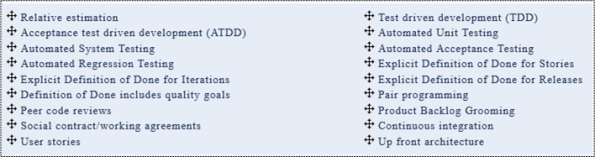

A Concrete Agile Practices List

Finally, I found out what someone actually thinks “agile practices” are. In “What are the Most Important and Adoption-Ready Agile Practices?”, Shane-Hastie presents his list:

Kudos to Shane for putting his list out there.

Ya gotta love all the “explicit definition of done” entries (“Aren’t you freakin’ done yet?“). And WTF is “Up front architecture” doing on the list? Isn’t that a no-no in agile-land? Shouldn’t it be “emergent architecture“? And no kanban board entry? What about burn down charts?

Alas, I can’t bulldozify Shane’s list too much. After all, I haven’t exposed my own agile practices list for scrutiny. If I get the itch, maybe I’ll do so. What’s on your list?

The Same Old Wine

Investment is to Goldman Sachs as management is to McKinsey & Co. These two prestigious institutions can do no wrong in the eyes of the rich and powerful. Elite investors and executives bow down and pay homage to Goldman McKinsey like indoctrinated North Koreans do to Kimbo Jongo Numero Uno.

As the following snippet from Art Kleiner’s “Who Really Matters” illustrates, McKinsey & Co, being chock full of MBAs from the most expensive and exclusionary business schools in the USA, is all about top-down management control systems:

…says McKinsey partner Richard Foster, author of Creative Destruction. If you ask companies how many control systems they have, they don’t know. If you ask them how much they’re spending on control, they say, ‘We don’t add it up like that.’ If you ask them to rank their control systems from most to least cost-effective, then cut out the twenty percent at the bottom, they can’t.” (And this from a partner at McKinsey, the firm whose advice has launched a thousand measurement and control systems.)

A dear reader recently clued BD00 into this papal release from a trio of McKinsey principals: “Enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of application development”. BD00 doesn’t know fer sure (when does he ever?), but he’ll speculate (when does he never?) that none of the authors has ever been within binoculars distance of a software development project.

Yet, they laughingly introduce a…

..viable means of measuring the output of application-development projects.

Their highly recommended application development control system is based on, drum roll please…. “Use Cases” (UC) and “Use Case Points” (UCP).

Knowing that their elite, money-hoarding, efficiency-obsessed, readers most probably have no freakin’ idea what a UC is, they painstakingly spend two paragraphs explaining the twenty year old concept (easily looked up on the web); concluding that…

..both business leaders and application developers find UCs easy to understand.

Well, yeah. Done “right“, UCs can be a boon to development – just like doing “agile” right. But how often have you ever seen these formal atrocities ever done right? Oh, I forgot. All that’s needed is “training” in how to write high quality UCs. Bingo, problem solved – except that training costs money.

Next up, the authors introduce their crown jewel output measurement metric, the “UCP“:

UCP calculations represent a count of the number of transactions performed by an application and the number of actors that interact with the application in question. UCPs, because they are simple to calculate, can also be easily rolled out across an organization.

So, how is an easily rolled out UCP substantively different than the other well known metric: the “Function Point” (FP)?

Another approach that’s often talked about for measuring output is Function Points. I have a little more sympathy for them, but am still unconvinced. This hasn’t been helped by stories I’ve heard of that talk about a single system getting counts that varied by a factor of three from different function point counters using the same system. – Martin Fowler

I guess that UCPs are superior to FPs because it is implied that given X human UCP calculators, they’ll all tally the same result. Uh, OK.

Not content to simply define and describe how to employ the winning UC + UCP metrics pair to increase productivity, the McKinseyians go on to provide one source of confirmation that their earth-shattering, dual-metric, control system works. Via an impressive looking chart with 12 project data points from that one single source (perhaps a good ole boy McKinsey alum?), they confidently proclaim:

Analysis therefore supports the conclusion that UCPs’ have predictive power.

Ooh, the words “analysis” and “predictive” and “power” all in one sentence. Simply brilliant; spoken directly in the language that their elite target audience drools over.

The article gets even more laughable (cry-able?) as the authors go on to describe the linear, step-by-step “transformation” process required to put the winning UC + UCP system in place and how to overcome the resistance “from below” that will inevitably arise from such a large-scale change effort. Easy as pie, no problemo. Just follow their instructions and call them for a $$$$$$ consultation when obstacles emerge.

So, can someone tell BD00 how the McKinsey UC + UCP dynamic duo is any different than the “shall” + Function Point duo? Does it sound like the same old wine in a less old bottle to you too?