Archive

Which One, And When?

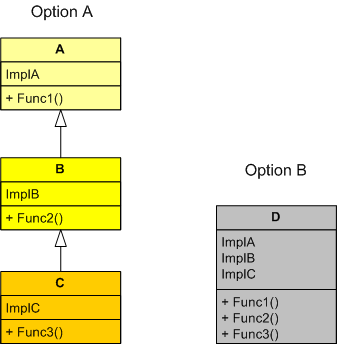

Option A and Option B in the UML figure below show two different ways of presenting the same 3-function interface to “other” code users. Under which conditions would you choose one design over the other?

Because I prefer simplicity over complexity and local dependency over distant dependency, I’d prefer option B over option A if I was reasonably sure that classes A and B wouldn’t be useful in another inheritance tree or useful as leaf classes. Even if I chose wrongly, because all the functionality is encapsulated within one class in option B, it wouldn’t be a huge risk for a user to extract out B or C class sub-functionality from D and customize it for his/her use by placing it in his/her own separate E class. In this case, no other existing clients of class D would be affected, but the trade off is the introduction of duplicate code into the code base. If I chose the option A inheritance tree, this wouldn’t be the case. In option A, if a user was allowed to directly change A and/or B in-situ, then the duplicate code “wart” wouldn’t manifest, but the risk of breaking the existing code of other users of the A, B, and/or C classes would be high compared to the alternative. Do you see any holes in this decision logic?

Movin’ On Up

For some unknown reason, I recently found myself reflecting back on how I’ve progressed as a software engineer over the years. After being semi-patient and allowing the fragmented thoughts to congeal, I neatly summed up the quagmire as thus:

- Single Node – Single Process – Single Threaded (SST) programming

- Single Node – Single Process – Multi-Threaded (SSM) programming

- Single Node – Multi-Process – Multi-Threaded (SMM) programming

- Multi-Node – Multi-Process – Multi-Threaded (MMM) programming

It’s interesting to note that my progression “up the stack” of abstraction and complexity did not come about from the execution of some pre-planned, grand master strategy . I feel that I was “tugged” by some unknown force into pursuing the knowledge and skills that have gotten me to a semi-proficient state of expertise in the design and programming of MMM systems.

Being a graphical type of dude, here’s a pictorial representation of how I “moved on up“.

How about you? Do you have a master plan for movin’ on up? Wherever you are in relation to this concocted stack, are you content to stay there – in the womb so-to-speak? If you want to adopt something like it as a roadmap for professional development, are you currently immersed in the type of environment that would allow you to do so?

Push And Pull Message Retrieval

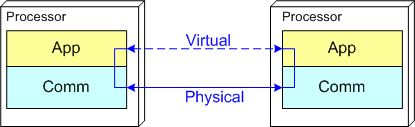

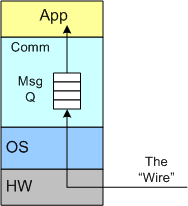

The figure below models a two layer distributed system. Information is exchanged between application components residing on different processor nodes via a cleanly separated, underlying communication “layer“. App-to-App communication takes place “virtually“, with the arcane, physical, over-the-wire, details being handled under the covers by the unheralded Comm layer.

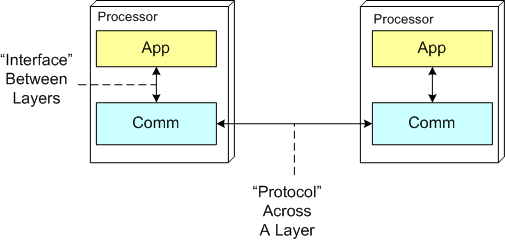

In the ISO OSI reference model for inter-machine communication, the vertical linkage between two layers in a software stack is referred to as an “interface” and the horizontal linkage between two instances of a layer running on different machines is called a “protocol“. This interface/protocol distinction is important because solving flow-control and error-control issues between machines is much more involved than handling them within the sheltered confines of a single machine.

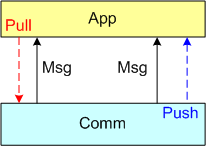

In this post, I’m going to focus on the receiving end of a peer-to-peer information transfer. Specifically, I’m going to explore the two methods in which an App component can retrieve messages from the comm layer: Pull and Push. In the “Pull” approach, message transfer from the Comm layer to the App layer is initiated and controlled by the App component via polling. In the “Push” method, inversion of control is employed and the Comm layer initiates/controls the transfer by invoking a callback function installed by the App component on initialization. Any professional Comm subsystem worth its salt will make both methods of retrieval available to App component developers.

The figure below shows a model of a comm subsystem that supplies a message queue between the application layer and the “wire“. The purpose of this queue is to prevent high rate, bursty, asynchronous message senders from temporarily overwhelming slow receivers. By serving as a flow rate smoother, the queue gives a receiver App component a finite amount of time to “catch up” with bursts of messages. Without this temporary holding tank, or if the queue is not deep enough to accommodate the worst case burst size, some messages will be “dropped on the floor“. Of course, if the average send rate is greater than the average processing rate in the receiving App, messages will be consistently lost when the queue eventually overflows from the rate mismatch – bummer.

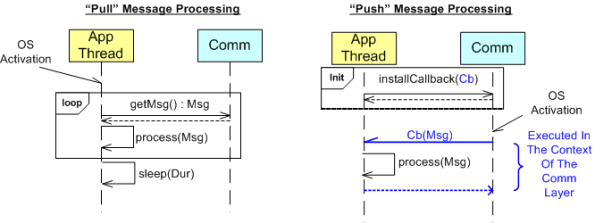

The UML sequence diagram below zeroes in on the interactions between an App component thread of execution and the Comm layer for both the “Push” and “Pull” methods of message retrieval. When the “Pull” approach is implemented, the OS periodically activates the App thread. On each activation, the App sucks the Comm layer queue dry; performing application-specific processing on each message as it is pulled out of the Comm layer. A nice feature of the “Pull” method, which the “Push” method doesn’t provide, is that the polling rate can be tuned via the sleep “Dur(ation)” parameter. For low data rate message streams, “Dur” can be set to a long time between polls so that the CPU can be voluntarily yielded for other processing tasks. Of course, the trade-off for long poll times is increased latency – the time from when a message becomes available within the Comm layer to the time it is actually pulled into the App layer.

In the”Push” method of message retrieval, during runtime the Comm layer activates the App thread by invoking the previously installed App callback function, Cb(Msg), for each newly received message. Since the App’s process(Msg) method executes in the context of a Comm layer thread, it can bog down the comm subsystem and cause it to miss high rate messages coming in over the wire if it takes too long to execute. On the other hand, the “Push” method can be more responsive (lower latency) than the “Pull” method if the polling “Dur” is set to a long time between polls.

So, which method is “better“? Of course, it depends on what the Application is required to do, but I lean toward the “Pull” Method in high rate streaming sensor applications for these reasons:

- In applications like sensor stream processing that require a lot of number crunching and/or data associations to be performed on each incoming message, the fact that the App-specific processing logic is performed within the context of the App thread in the “Pull” method (instead of the Comm layer) means that the Comm layer performance is not dependent on the App-specific performance. The layers are more loosely coupled.

- The “Pull” approach is simpler to code up.

- The “Pull” approach is tunable via the sleep “Dur” parameter.

How about you? Which do you prefer, and why?

Mismatch

Assume that you’re tasked to create a two component, distributed software system as shown in the figure below. The nature of the application is such that during runtime, component 1 will continuously transmit a “bursty“, asynchronous stream of messages to component 2. During evolution of the system in the future, you know that more and more stages will be tacked on to the “pipeline“, with each stage adding value to a growing customer base (if you don’t screw it up and hatch a BBoM).

Note that the relationship between application components is peer-to-peer and not client-server like this:

One question is this: “Why on earth would anyone choose a client-server messaging system (with peer-to-peer capability tacked on) over a peer-to-peer messaging system for this class of application?“. The question especially applies to product organizations that strive to develop distinctly elegant and innovative solutions – which hopefully includes yours. A second question is: “What would technologically savvy customers think?“. Of course, if you think your customers are dumb-asses (and you won’t be in business for long if you do) and can’t tell the difference, then the situation is a “don’t care“, no?

Flouting Convention

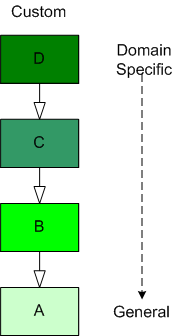

As software-centric systems get more complex, one of the most effective tools for preventing the creation of monstrous BBoMs downstream is “layering”. The figure below shows a generic model of the layering concept.

When you use layering, you partition your system into a vertical stack with the most “exciting” application-specific functions and objects at the top of the stack and the more mundane and boring functionality down in the basement. In a pure layered system, the higher layers depend on the services provided by the lower levels and there are no dependencies the other way. The cleaner and crisper your inter-layer boundaries, the lower your maintenance cost and frustration.

The figure below shows the conventional approach of representing an inheritance hierarchy in an object oriented design. What’s wrong with this picture? Relative to the layered model, it’s “upside down“. The most general class is on top and the most domain-specific class is at the bottom. WTF and D’oh!

Since “layering” has been around much longer than object-orientation, Bulldozer00 thinks that a layered, object-oriented software system should always be presented to stakeholders like this:

This method of representation aligns cleanly with the layered “view” of the system and is thus, less confusing and dis-orienting to all audiences, dontcha think? To hell with convention, – at least in this situation.

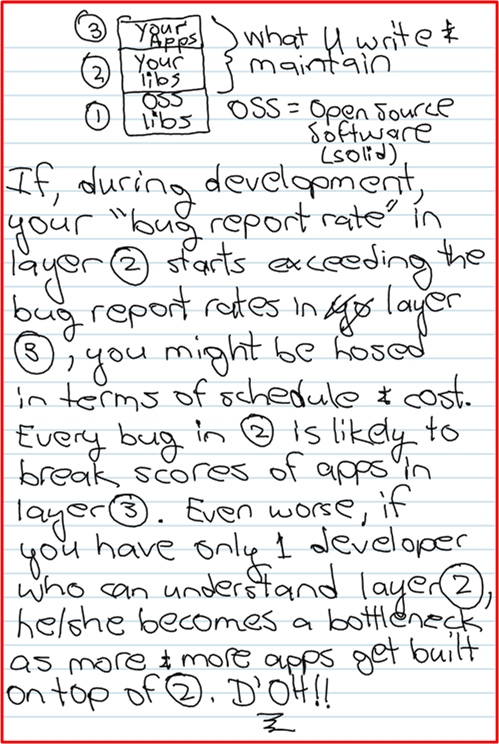

Bug Reporting Rate

An Answer 10 Years Later

I’ve always questioned why one of my mentors from afar, Steve Mellor, was one of the original signatories of the “Agile Manifesto” 10 years ago. He’s always been a “model-based” guy and his fellow pioneer agile dudes were obsessed with the idea that source code was the only truth – to hell with bogus models and camouflage documents. Even Grady Booch, another guy I admire, tempered the agilist obsession with code by stating something like this: “the code is the truth, but not the whole truth“.

Stephen recently sated my 10 year old curiosity in this InfoQ interview: “A Personal Reflection on Agile Ten Years On“. Here’s Steve’s answer to the question that haunted me fer 10 ears:

The other signatories were kind enough, back in 2001, to write the manifesto using the word “software” (which can include executable models), not “code” (which is more specific.) As such I felt able, in good conscience, to become a signatory to the Manifesto while continuing to promote executable modeling. Ten years on we have a standard action language for agile modeling. – Stephen J. Mellor

The reason I have great respect for Stephen (and his cohort Paul Ward) is this brilliant trilogy they wrote waaaayy back in the mid 80s:

Despite the dorky book covers and the dates they were written, I think the info in these short tomes is timeless and still relevant to real-time systems builders today. Of course, they were created before the object-oriented and multi-core revolutions occurred, but these books, using simple DeMarco/Plauger structured analysis modeling notation (before UML), nail it. By “it”, I mean the thinking, tools, techniques, idioms, and heuristics required to specify, design, and build concurrent, distributed, real-time systems that work. Buy em, read em, decide for yourself, bookmark this post, and please report your thoughts back to me.

Fully Qualified

When I’m coerced into inheriting from one or more base classes to reuse pre-existing functionality, I prefer to fully qualify my calls to base class member functions like this:

Coding this way helps me to keep a conceptual separation between classes and eases downstream maintenance – I know where to look for the function definitions. Since I’m a “has a” instead of an “is a” programmer, I prefer black box composition over white box inheritance; unless it’s necessary or authoritative coercion is involved. How about you? What’s your preference?

Ammunition Depot

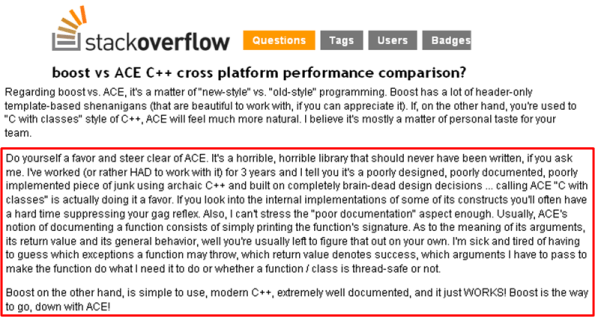

In preparation for a debate, both sides usually spend some time amassing evidence that supports their distorted view of the issue. Well, this post is intended to serve as a repository for my distorted side of an ongoing debate.

All the above snippets were strategically and carefully culled from various discussions posted on the wonderful Joel Spolsky and Jeff Atwood site: Stackoverflow.com.

Hard To Misuse

I’ve seen the programming advice “design interfaces to be hard to misuse” repeated many times by many different gurus over the years. Because of this personal experience, I just auto-assumed (which is not a smart thing to do!) all experienced C++ developers: knew it, took it to heart, and thought twice before violating it.

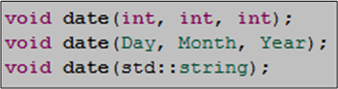

Check out the three date() function prototype declarations below. If you were responsible for designing and implementing the function for a library that would be used by your team mates, which interface would you choose to offer up to your users? Which one do you think is the “hardest to misuse“, and why?