Archive

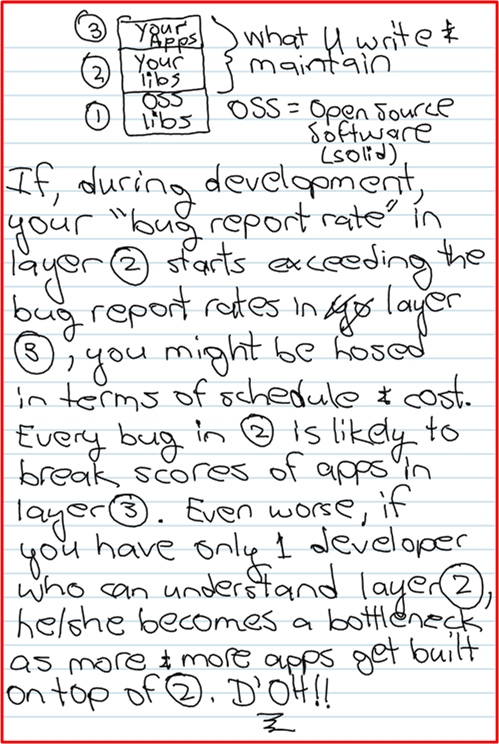

Bug Reporting Rate

Dissin’ Boost

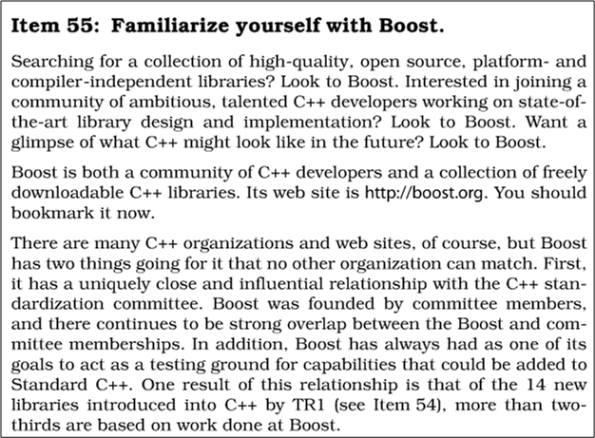

To support my yearning for learning, I continuously scan and probe all kinds of forums, books, articles, and blogs for deeper insights into, and mastery of, the C++ programming language. In all my external travels, I’ve never come across anyone in the C++ community that has ever trashed the boost libraries. Au contraire, every single reference that I’ve ever seen has praised boost as a world class open source organization that produces world class, highly efficient code for reuse. Here’s just one example of praise from Scott Meyers‘ classic “Effective C++: 55 Specific Ways To Improve Your Programs And Designs“:

Notice that in the first paragraph, I wrote the word external in bold. Internal, which means “at work” where politics is always involved, is another story. Sooooo, let me tell you one.

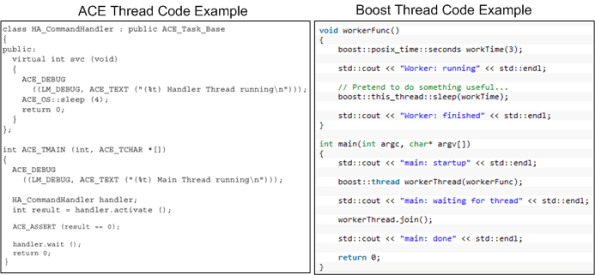

Years ago, a smart, highly productive, and dedicated developer who I respect started building a distributed “framework” on top of the ACE library set (not as a formal project – on his own time). There’s no doubt that ACE is a very powerful, robust, and battle-tested platform. However, because it was designed back in the days when C++ compiler technology was immature, I think its API is, let’s say “frumpy“, unconventional, and (dare I say) “obsolete” compared to the more modern Boost APIs. Boost-based code looks like natural C++, whereas ACE-based code looks like a macro derived dialect. In the functional areas where ACE and Boost overlap (which IMHO is large), I think that Boost is head over heels easier to learn and use. But that’s just me, and if you’re a long-time ACE advocate you might be mad at me now because you’re blinded by your bias – just like I am blinded by mine.

Fast forward to the present moment after other groups in the company (essentially, having no choice) have built their one-off applications on top of the homegrown, ACE-based, framework. Of course, you know through experience that “homegrown” means:

- the framework API is poorly documented,

- the build process is poorly documented,

- forks have been spawned because of the lack of a formally funded maintenance team and change process,

- the boundary between user and library code is jagged/blurry,

- example code tutorials are non-existent.

- it is most likely to cost less to build your own, lighter weight framework from scratch than to scale the learning curve by studying tens of 1,000s of lines of framework code to separate the API from the implementation and figure out how to use the dang thing.

Despite the time-proven assertions above, the framework author and a couple of “other” promoters who’ve never even tried to extract/build the framework, let alone learn the basics of the “jagged” API and write a simple sample distributed app on top of it, have naturally auto-assumed that reusing the framework in all new projects will save the company time and money.

Along comes a new project in which the evil Bulldozer00 (BD00) is a team member. Being suspicious of the internal marketing hype, and in response to the “indirect pressure and unspoken coercion” to architect, design, and build on top of the one and only homegrown framework, BD00 investigates the “product“. After spending the better part of a week browsing the code base and frustratingly trying to build the framework so that he could write a little distributed test app, BD00 gives up and concludes that the bulleted list definition above has withstood the test of time….. yet again.

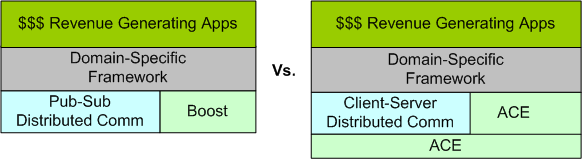

When other members of BD00’s team, including one member who directly used the ACE-based framework on a previous project, investigate the qualities of the framework, they come to the same conclusion: thank you, but for our project, we’ll roll our own lighter weight, more targeted, and more “modern” framework on top of Boost. But of course, BD00 is the only politically incorrect and blatantly over-the-top rejector of the intended one-size-fits-all framework. In predictable cause-effect fashion, the homegrown framework advocates dig their heels in against BD00’s technical criticisms and step up their “cost and time savings” rhetoric – including a diss against Boost in their internal marketing materials. Hmmm.

Since application infrastructure is not a company core competence and certainly not a revenue generator, BD00 “cleverly” suggests releasing the framework into the open source community to test its viability and ability to attract an external following. The suggestion falls on deaf ears – of course. Even though BD00 (who’s deliberately evil foot-in-mouth approach to conflict-handling almost always triggers the classic auto-reject response in others) made the helpful(?) suggestion, the odds are that it would be ignored regardless of who had made it. Based on your personal experience, do you agree?

Note 1: If interested, check out this ACE vs Boost vs Poco libraries discussion on StackOverflow.com.

Note2: There’s a whole ‘nother sensitive socio-technical dimension to this story that may trigger yet another blog post in the future. If you’ve followed this blog, I’ve hinted about this bone of contention in several past posts. The diagram below gives a further hint as to its nature.

Avoiding The Big Ball Of Mud

Like other industries, the software industry is rife with funny and quirky language terms. One of my favorites is “Big Ball of Mud“, or BBoM. A BBoM is a mess of a software system that starts off soft and malleable but turns brittle and unstable over time. Inevitably, it hardens like a ball of mud baking in the sun; ready to crumble and wreak havoc on the stakeholder community when disturbed. D’oh!

“And they looked upon the SW and saw that it was good. But they just had to add one more feature…”

Joseph Yoder, one of the co-creators of “BBoM” along with Brian Foote, recently gave a talk titled “Big Balls of Mud in Agile Development: Can We Avoid Them?“. Out of curiosity and the desire to learn more, I watched a video of the talk at InfoQ. In his talk, Mr. Yoder listed these agile tenets as “possible” BBoM promoters:

- Lack of upfront design (i.e. BDUF)

- Embrace late changes to requirements

- Continuous evolving architecture

- Piecemeal growth

- Focus on (agile) process instead of architecture

- Working code is the one true measure of success

For big software systems, steadfastly adhering to these process principles can hatch a BBoM just as skillfully as following a sequential and prescriptive waterfall process. It’ll just get you to the state of poverty that always accompanies a BBoM much quicker.

Unlike application layer code, infrastructure code should not be expected to change often. Even small architectural changes can have far reaching negative effects on all the value-added application code that relies on the structure and general functionality provided under the covers. If you look hard at Joe’s list, any one of his bullets can insidiously steer a team off the success profile below – and lead the team straight to BBoM hell.

Bugs Or Cash

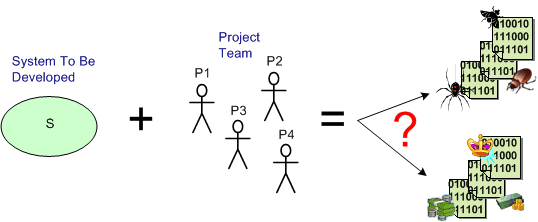

Assume that you have a system to build and a qualified team available to do the job. How can you increase the chance that you’ll build an elegant and durable money maker and not a money sink that may put you out of business.

The figure below shows one way to fail. It’s the well worn and oft repeated ready-fire-aim strategy. You blast the team at the project and hope for the best via the buzz phrase of the day – “emergent design“.

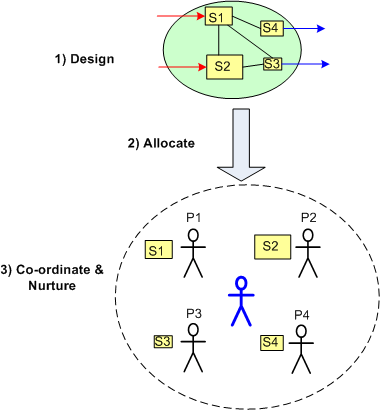

On the other hand, the figure below shows a necessary but not sufficient approach to success: design-allocate-coordinate. BTW, the blue stick dude at the center, not the top, of the project is you.

On the other hand, the figure below shows a necessary but not sufficient approach to success: design-allocate-coordinate. BTW, the blue stick dude at the center, not the top, of the project is you.

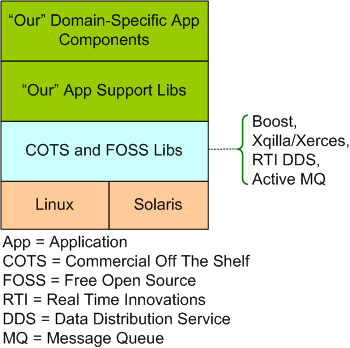

Our Stack

The model below shows “our stack”. It’s a layered representation of the real-time, distributed software system that two peers and I are building for our next product line. Of course, I’ve intentionally abstracted away a boatload of details so as not to give away the keys to the store.

The code that we’ve written so far (the stuff in the funky green layers) is up to 50K SLOC of C++ code and we guesstimate that the system will stabilize at around 250K SLOC. In addition to this computationally intensive back end, our system also includes a Java/PHP/HTML display front end, but I haven’t been involved in that area of development. We’ve been continuously refactoring our “App Support Libs” layer as we’ve found turds in it via testing the multi-threaded, domain-specific app components that use them.

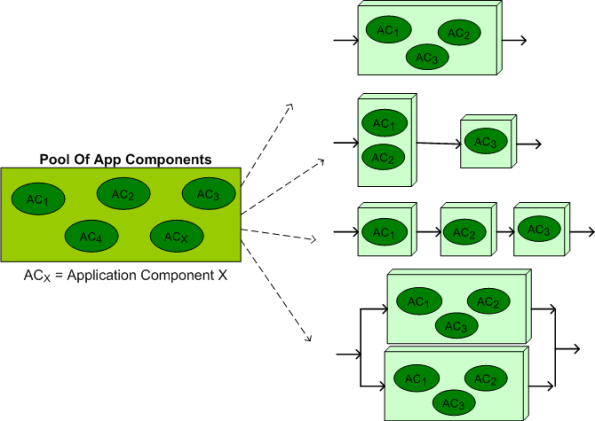

The figure below illustrates the flexibility and scalability of our architecture. From our growing pool of application layer components, a large set of product instantiations can be created and deployed on multiple hardware configurations. In the ideal case, to minimize end-to-end latency, all of the functionality would be allocated to a single processor node like the top instantiation in the figure. However, at customer sites where processing loads can exceed the computing capacity of a single node, voila, a multi-node configuration can be seamlessly instantiated without any source code changes – just XML file configuration parameter changes. In addition, as the bottom instantiation shows, a fault tolerant, auto-failover, dual channel version of the system can be deployed for high availability, safety-critical applications.

Communication Layer Performance Benchmarking

Along with two outstanding and dedicated peers, I’m currently designing and writing (in C++) a large, distributed, multi-process, multi-threaded, scalable, real-time, sensor software system. Phew, that’s a lot of “see how smart I am” techno-jargon, no?

Since the performance and reliability of the underlying Inter-Process Communication (IPC) layer is critical to meeting our customer’s end-to-end system latency and throughput requirements, we decided to measure the performance of three different IPC candidates:

- Real Time Innovations Inc.’s implementation of the Object Management Group’s Data Distribution Service (DDS) standard

- The Apache Software Foundation’s ActiveMQ implementation of the Java Messaging System (JMS) standard

- A homegrown brew built on top of the Boost Organization‘s Asio (Asychronous input output) portable C++ library.

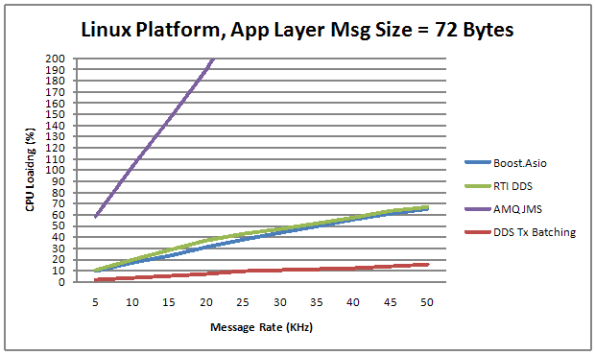

The figure below shows the average CPU load vs throughput performance of the three distributed system messaging communication candidates. Notice that the centralized broker-based JMS approach yielded horrendous relative results.

Transmit batching, along with a whole bevy of “free” (to application layer programmers) tunable features in RTI’s DDS, consists of aggregating a bunch of application layer messages into one network packet to increase the throughput (at the expense of increased latency). Since batching isn’t available in AMQ JMS or our “homegrown” Boost.Asio comm layer candidate, only the DDS performance increase is shown on the graph.

Measurement Approach

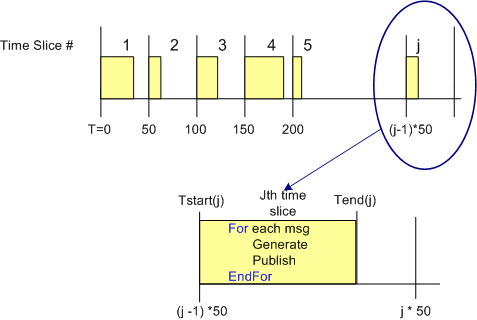

One way to measure the CPU load imposed on a processor node by an IPC layer candidate in a data streaming, real-time, system is to quantize time into discrete slices and measure the per slice processing time that it takes to send a fixed number of messages out via the comm software stack. Since other non-deterministic OS runtime functionality shares the CPU with the application processes and the comm software stack, measuring and averaging the normalized CPU time across a large number of slices can give some quantitative feel for the load imposed on the processor.

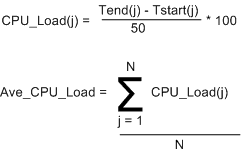

The figure below shows the approach that was taken to measure the CPU load versus throughput performance of the three communication layer candidates. To implement this strategy, I wrote a small C++ test application that is designed to operate in a time sliced mode, where the time slice size (default = 50 msecs) is user selectable via the command line.

During runtime, the test app generates and publishes a stream of “canned” messages at a user specified rate and for a user-defined test run duration. Upon the start of each time slice, the current time is “grabbed” and stored for later use. At the end of each tight, K-message, generate-and-publish loop, the end time is retrieved from the OS and then the percent CPU load for the slice is calculated in accordance with the simple equations below. At the end of the test run, the first 1000 sample points are averaged, and the result, along with the max and min loads measured during the run are printed to the console and a date stamped log file.

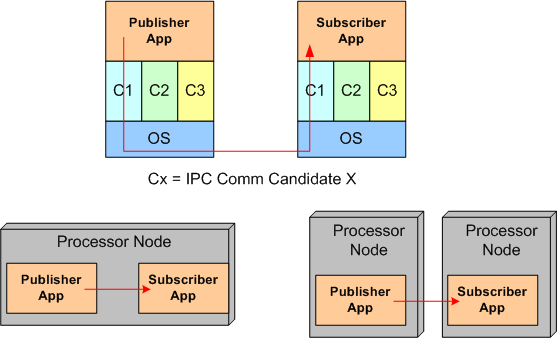

Of course, to ensure that the comm layer candidate wasn’t dropping or corrupting application messages during test runs, I wrote a subscriber app to provide a “resistor load” on the performance measuring publisher app process. By comparing the number and integrity of messages received to the number and integrity of those transmitted, the measurements were given higher credibility. The figure below shows the test fixtures that I ran the performance tests on. For the AMQ JMS candidate, a broker process was running along side of the app processes, but his single-point-of-failure component is not shown in the diagram.

Of course, to ensure that the comm layer candidate wasn’t dropping or corrupting application messages during test runs, I wrote a subscriber app to provide a “resistor load” on the performance measuring publisher app process. By comparing the number and integrity of messages received to the number and integrity of those transmitted, the measurements were given higher credibility. The figure below shows the test fixtures that I ran the performance tests on. For the AMQ JMS candidate, a broker process was running along side of the app processes, but his single-point-of-failure component is not shown in the diagram.

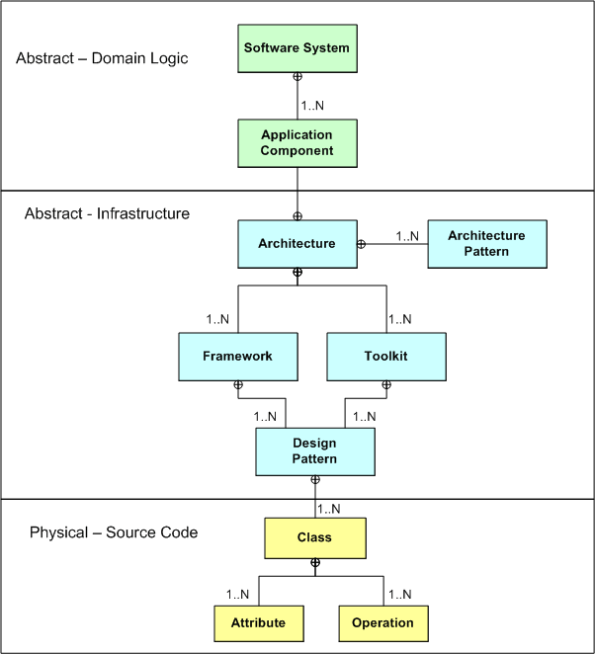

Domain, Infrastructure, And Source

Via a simple SysML diagram that solely uses the “contains” relationship icon (the circled crosshairs thingy) , here’s Bulldozeroo’s latest attempt to make sense of the relationships between various levels of abstraction in the world of software as he knows it today. Notice that in Bulldozer00’s world, where the sky is purple, the architecture is at the center of the containment hierarchy.

Unconstraining UML And SysML Modeling Tools

For informal, rapid, and iterative design modeling and intra-team communication, I use the freely downloadable and unconstraining UML and SysML stencil plugins for visio. These handy little stencils are available here: Visio UML and SysML stencils homepage. When installed and opened, the shapes window may look like the figure below. Of course, you can control which shapes sub-windows you’d like to display and use within a document via the file->shapes menu selection. Open all 11 of them if you’d like!

If you compare the contents of the two sets of shape stencils, since UML is a subset and extension of UML you’ll unsurprisingly find a lot of overlap in the smart symbol sets. Note that unlike the two UML stencils, the set of nine SysML stencils are “SysML Diagram” oriented. Because of this diagram-centric decomposition, I find myself using the SysML stencils more than the UML stencils.

To use the stencils, you just grab, drag, and drop symbols onto the canvas; tying them together with various connector symbols. Of course, each symbol is “smart”, so right-clicking on a shape triggers a context sensitive menu that gives you finer control over the attributes and display properties of the shape.

To use the stencils, you just grab, drag, and drop symbols onto the canvas; tying them together with various connector symbols. Of course, each symbol is “smart”, so right-clicking on a shape triggers a context sensitive menu that gives you finer control over the attributes and display properties of the shape.

If you don’t want to open the stencils manually, you can create either a new SysML or UML document from the templates that are co-installed with the stencils (file->new->choose drawing type->SysML). In this case, either the 2 UML stencils, or all 9 SysML stencils are auto-opened when the first page of the new document is created and displayed. I often use the multi-page feature of visio to create a set of associated behavior and structure diagrams for the design that I’m working on, or to reverse-engineer a section of undecipherable code that I’m struggling to understand.

If you’re a visio user and you’re looking to learn UML and/or SysML, I think experimenting with these stencils is a much better learning alternative than using one of the big, formal, and more hand-cuffing tools like Artisan Studio or Sparx Enterprise Architect. You can “Bend it like Fowler” much more easily with the visio stencils approach and not get frustrated as often.

A Pencast

Checkout my “pencast” of the legendary Grady Booch talking about software architecture. In this notes+audio mashup, Grady expounds on the importance of patterns within elegant and robust architectures. Don’t mind my wife and dog’s barking, uh, I mean my dog’s barking and my wife’s talking, in a small segment of the pencast.

Related Articles

- Digital Pen Gives Boring Note Taking a Modern Kick (wired.com)

- Livescribe use models in special education (zdnet.com)

- The future of the pen? (building43.com)

- Livescribe Introduces Next Generation Hardware and Software Smartpen System – Review (geardiary.com)

Yes I do! No You Don’t!

“Jane, you ignorant slut” – Dan Ackroid

In this EETimes post, I Don’t Need No Stinkin’ Requirements, Jon Pearson argues for the commencement of coding and testing before the software requirements are well known and recorded. As a counterpoint, Jack Ganssle wrote this rebuttal: I Desperately Need Stinkin Requirements. Because software industry illuminaries (especially snake oil peddling methodologists) often assume all software applications fit the same mold, it’s important to note that Pearson and Gannsle are making their cases in the context of real-time embedded systems – not web based applications. If you think the same development processes apply in both contexts, then I urge you to question that assumption.

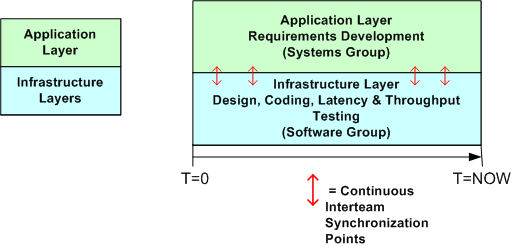

I usually agree with Ganssle on matters of software development, but Pearson also provides a thoughtful argument to start coding as soon as a vague but bounded vision of the global structure and base behavior is formed in your head. On my current project, which is the design and development of a large, distributed real-time sensor that will be embedded within a national infrastructure, a trio of us have started coding, integrating, and testing the infrastructure layer before the application layer requirements have been nailed down to a “comfortable degree of certainty”.

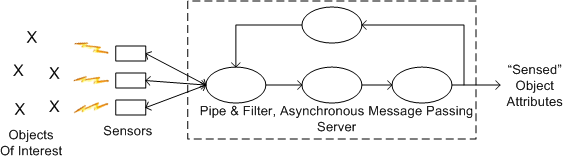

The simple figures below show how we are proceeding at the current moment. The top figure is an astronomically high level, logical view of the pipe-filter archetype that fits the application layer of our system. All processes are multi-threaded and deployable across one or more processor nodes. The bottom figure shows a simplistic 2 layer view of the software architecture and the parallel development effort involving the systems and software engineering teams. Notice that the teams are informally and frequently synchronizing with each other to stay on the same page.

The main reason we are designing and coding up the infrastructure while the application layer requirements are in flux is that we want to measure important cross-cutting concerns like end-to-end latency, processor loading, and fault tolerance performance before the application layer functionality gets burned into a specific architecture.

The main reason we are designing and coding up the infrastructure while the application layer requirements are in flux is that we want to measure important cross-cutting concerns like end-to-end latency, processor loading, and fault tolerance performance before the application layer functionality gets burned into a specific architecture.

So, do you think our approach is wasteful? Will it cause massive, downstream rework that could have been avoided if we held off and waited for the requirements to become stable?