Archive

Auto Forgetfulness

The other day, I started tracking down a defect in my C++11 code that was exposed by a unit test. At first, I thought the bugger had to be related to the domain logic I was implementing. However, after 4 hours of inspection/testing/debugging, the answer simply popped into my head, seemingly out of nowhere (funny how that works, no?). It was due to my “forgetting” a subtle characteristic of the C++11 automatic type deduction feature implemented via the “auto” keyword.

To elaborate further, take a look at this simple function prototype:

SomeReallyLongTypeName& getHandle();

On first glance, you might think that the following call to getHandle() would return a reference to an internal, non-temporary, object of type SomeReallyLongTypeName that resides within the scope of the getHandle() function.

auto x = getHandle();

However, it doesn’t. After execution returns to the caller, x contains a copy of the internal, non-temporary object of type SomeReallyLongTypeName. If SomeReallyLongTypeName is non-copyable, then the compiler would have mercifully clued me into the problem with an error message (copy ctor is private (or deleted)).

To get what I really want, this code does the trick:

auto& x = getHandle();

The funny thing is that I already know “auto” ignores type qualifications from routinely writing code like this:

std::vector<int> vints{};

//fill up "vints" somehow

for(auto& elem : vints) {

//do something to each element of vints

}

However, since it was the first time I used “auto” in a new context, its type-qualifier-ignoring behavior somehow slipped my feeble mind. I hate when that happens.

Staying Sane

Standardization is long periods of mind-numbing boredom interrupted by moments of sheer terror – Bjarne Stroustrup

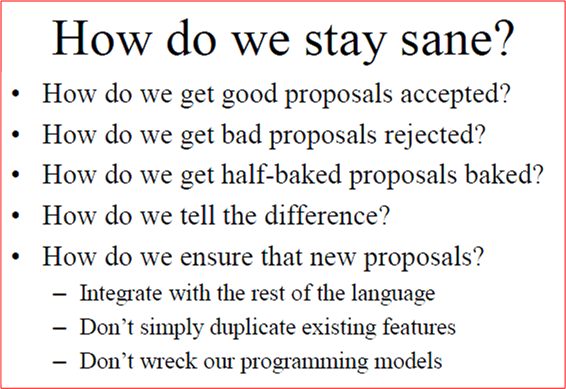

In his ACCU2013 talk, “C++14 Early Thoughts“, Bjarne Stroustrup presented this slide:

By using “we” in each bullet point, Bjarne was referring to the ISO WG-1 C++ committee and the daunting challenges it faces to successfully move the language forward.

Not only do the committee leaders have to manage the external onslaught of demands from a huge, dedicated user base, they have to homogenize the internal communications amongst many smart and assertive members. To illustrate the internal management problem, Bjarne said something akin to: “There is no topic the committee isn’t willing to discuss at length for two years“.

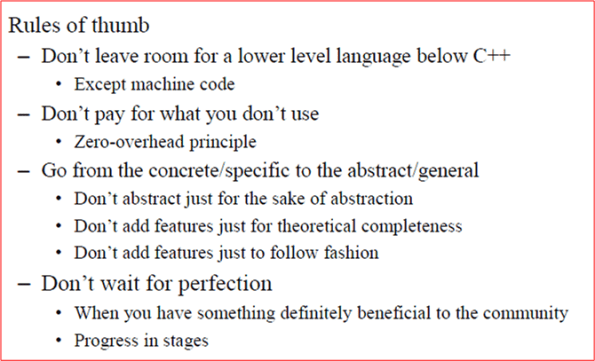

In order to prevent being overwhelmed with work, the committee uses this set of grass roots principles to filter out the incoming chaff from the wheat:

I have no idea how internal conflicts are handled, nor how infinite loops of technical debate are exited, but since the all-volunteer committee is still functioning and doing a great job (IMO) of modernizing the language, there’s got to be some magic at work here:

Management Idiots And Programming Idioms

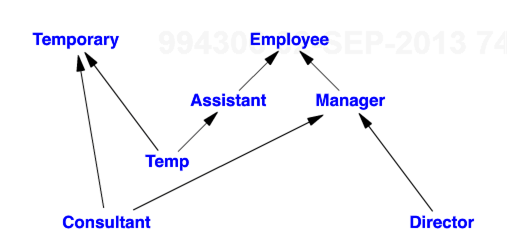

In TC++PL, Bjarne Stroustrup introduces the concept of a class hierarchy with this simple business world example:

Temporary and Employee base class “objects” get paid by the company to do work that directly creates value. Manager objects inherit an Employee’s responsibilities and encapsulate new, manager-specific, behaviors; like monitoring/commanding/reprimanding non-manager Employees, Temps, and Assistants. Proceeding down the inheritance tree on the right, a Director object inherits the behaviors of both the Manager and Employee classes while adding new “directorial” behaviors.

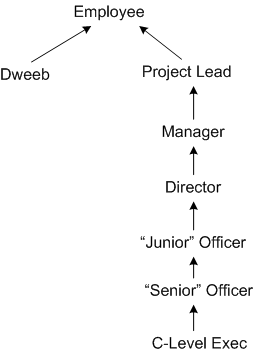

When BD00 saw Bjarne’s inheritance tree example, he said to himself “Dude, you got it wrong. If you wanted to model the real world, here’s what you shoulda presented“:

It woulda added a touch of edgy humor to the book, dontcha think?

When I write my first programming book, I’m gonna have diagrams like that and code fragments like this in it:

I’m thinking of hatching a kickstarter.com project and titling the hybrid book something like “Management Idiots And Programming Idioms“. What would you name it, and would you buy it?

The Right Tool For The Job

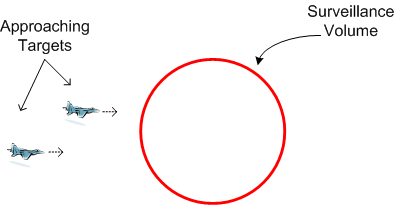

The figure below depicts a scenario where two targets are just about to penetrate the air space covered by a surveillance radar.

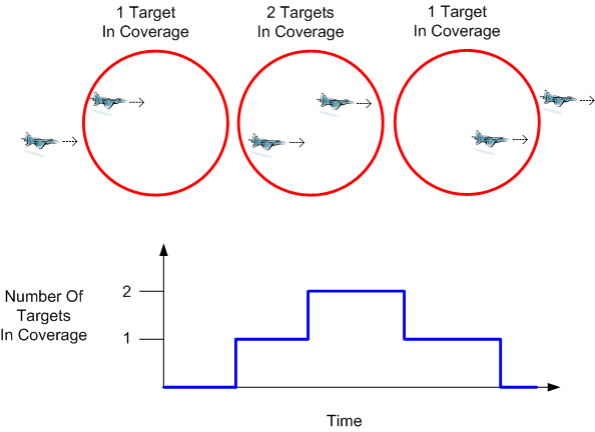

The next sequence of snapshots illustrates the targets entering, traversing, and exiting the coverage volume.

Assume that the surveillance volume is represented in software as a dynamically changing, in-memory database of target objects. On system startup, the database is initialized as empty. During operation, targets are inserted, updated, and deleted in response to changes that occur in the “real” world.

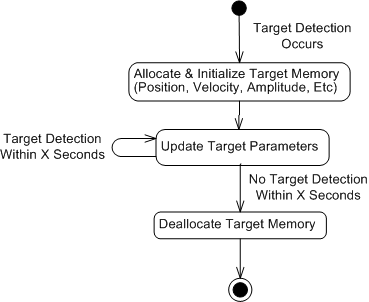

The figure below models each target’s behavior as a state transition diagram (STD). The point to note is that a target in a radar application is stateful and mutable. Regardless of what functional language purists say about statefulness and mutability being evil, they occur naturally in the radar application domain.

Note that the STD also indicates that the application domain requires garbage collection (GC) in the form of deallocation of target memory when a detection hasn’t been received within X seconds of the target’s prior update.

Since the system must operate in real-time to be useful, we’d prefer that the target memory be deleted as soon as the real target it represents exits the surveillance volume. We’d prefer the GC to be under the direct, local, control of the programmer and not according to the whims of an underlying, centralized, virtual machine whose GC kicks it whenever it feels like it.

With these domain-specific attributes in mind, C++ seems like the best programming language fit for real-time radar domain applications. The right tool for the job, no? If you disagree, please state your case.

The Biggest Cheerleader

Herb Sutter is by far the biggest cheerleader for the C++ programming language – even more so than the language’s soft spoken creator, Bjarne Stroustrup. Herb speaks with such enthusiasm and optimism that it’s infectious.

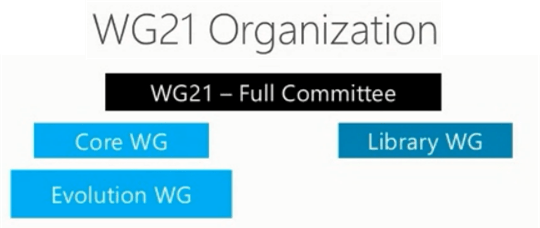

In his talk at the recently concluded GoingNative2013 C++ conference, Herb presented this slide to convey the structure of the ISO C++ Working Group 21 (WG21):

On the left, we have the language core and language evolution working groups. On the right, we have the standard library working group.

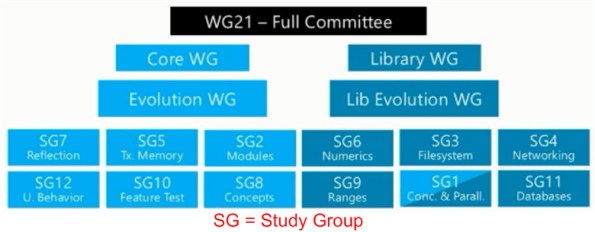

But wait! That was the organizational structure as of 18 months ago. As of now, we have this decomposition:

As you can see, there’s a lot of volunteer effort being applied to the evolution of the language – especially in the domain of libraries. In fact, most of the core language features on the left side exist to support the development of the upcoming libraries on the right.

In addition to the forthcoming minor 2014 release of C++, which adds a handful of new features and fixes some bugs/omissions from C++11, the next major release is slated for 2017. Of course, we won’t get all of the features and libraries enumerated on the slide, but the future looks bright for C++.

The biggest challenge for Herb et al will be to ensure the conceptual integrity of the language as a whole remains intact in spite of the ambitious growth plan. The faster the growth, the higher the chance of the wheels falling off the bus.

“The entire system also must have conceptual integrity, and that requires a system architect to design it all, from the top down.” – Fred Brooks

“Who advocates … for the product itself—its conceptual integrity, its efficiency, its economy, its robustness? Often, no one.” – Fred Brooks

I’m not a fan of committees in general, but in this specific case I’m confident that Herb, Bjarne, and their fellow WG21 friends can pull it off. I think they did a great job on C++11 and I think they’ll perform just as admirably in hatching future C++ releases.

The Hodgepodge Myth

There are two kinds of languages. Those that everyone complains about and those that nobody uses. – Bjarne Stroustrup

I’ve seen C++ described as a thoughtless hodgepodge of features and approaches that were carelessly slapped together and foist upon the programming community. However, if any of those detractors read “The Design And Evolution Of C++” and dive deeply into the language’s technical details, they might change their minds and marvel at the essential complexity baked into C++.

As a systems programming language whose target niche is infrastructure and constrained-resource (CPU speed and memory) applications, C++ is all about achieving efficient abstraction (as opposed to increasing programmer productivity). For efficiency, its constructs must not move too far away from how computing hardware actually stores and manipulates data (linear arrays, pointers, stack-based variables). Otherwise, a “hidden” layer of translational code must be inserted between what the programmer actually writes and the code that actually runs on the hardware. To write large, domain-specific programs, C++ must also provide abstraction facilities for implementing domain concepts and inter-concept relationships directly in code (classes, inheritance, friendship, templates, namespaces, exceptions, meta-programming).

Comparatively speaking, no other high level language comes close to achieving the blend of abstraction and efficiency that C++ attains. Sure, there are many newer languages that increase programmer productivity by decreasing verbosity, increasing levels of abstraction, and insulating the programmer from details, but the price paid for this productivity gain is a loss in runtime performance, a shallow understanding of what goes on underneath the covers, and long stretches of optimization/tuning efforts to meet performance requirements.

Once an engineer forms a string opinion on a technical tool or methodology, she is unlikely to change it – no matter what evidence is placed in front of her. As regular readers of this ball-busting blog know, BD00 chronically suffers from this “fan boy” malady all too well. And this post is a prime example of that behavioral trait.

It’s Definitely A Compiler Bug

Previously, I wrote a post about a potential compiler bug with the g++ compiler in the GCC 4.7.2 collection that was driving me nutz: “Uniform Initialization Failure?“. In that post, I flip-flopped between concluding whether the issue I stumbled upon was a bug or just another one of those C++ quirks that cause newbie programmers to flee in droves toward the easier-to-learn programming languages. D’oh!

Since I wrote that post, I’ve purchased and have been studying the fourth edition of Bjarne’s TCPPL. It’s now a slam dunk. The g++ GCC 4.7.2 compiler does indeed have a bug in its implementation of C++11’s uniform initialization feature.

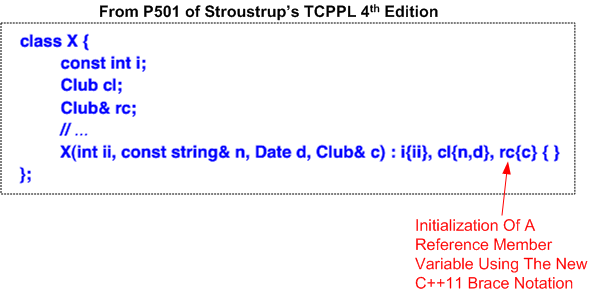

First, consider this Stroustrup code snippet:

Note how Bjarne “uniformly” uses braces to initialize all of class X‘s member variables – including the Club reference member variable, rc.

Next, look at the code I wrote that makes g++ 4.7.2 barf:

Note how the compiler spewed blasphemy when I tried to uniformly use braces to initialize the GccBug class’s foo and bar member variables.

Now, look at what I had to do to make the almighty compiler happy:

As you can see, I had to destroy the elegancy of uniform initialization by employing a mix of braces and old-style parenthesis to initialize the foo and bar member variables.

It’s my understanding that GCC 4.8.2 has been released and it has been deemed C++11 feature-complete. I currently don’t have it installed, but, if one of you dear readers are using it, can you please experiment with it and determine if the bug has been squashed? I have a highly coveted BD00 T-shirt waiting in the warehouse for the first person who reports back with the result.

Don’t Panic!

The fourth edition of “The C++ Programming Language” weighs in at 1346 pages and 44 chapters allocated over four partitions. The end of each chapter provides a list of advisory items – yielding a grand total of 699 nuggets of general programming and C++ specific wisdom for the reader to ponder.

The figure below shows a breakdown of the behemoth book’s table of contents. The number of advisories provided in each chapter and each partition are shown on the right side.

As a temporary excursion from reading and studying and writing exploratory snippets of C++11 code, I went through all 699 items and plucked out a subset of the tidbits I found most useful. Of course, your personal list would no doubt turn out differently.

Even though it’s not on my list, my absolute favorite item of advice is the first one presented at the end of chapter 2:

D’oh! Wanna guess at how much time is needed for all to become clear? Maybe Malcolm Gladwell‘s famous “10,000 hours” isn’t enough? But that’s why I love C++. It provides an endlessly rich and deep opportunity for learning.