Archive

C++ Dudes To Follow

If you’re a twit like me, and you also “do” C++, you might want to follow these people and resources on twitter:

They don’t tweet much, but when they do, they’re worth listening to. Do you know of any other C++ twitter resources that I should add to my list?

Performance Playground

Since I work on real-time software projects where tens of thousands of data samples per second must be filtered, manipulated, and transformed into higher level decision-support information, performance in the main processing pipeline is important. If the software can’t keep up with the unrelenting onslaught of data streaming in from the “real world“, internal buffers/queues will overflow at best and the system will crash at worst. D’oh!

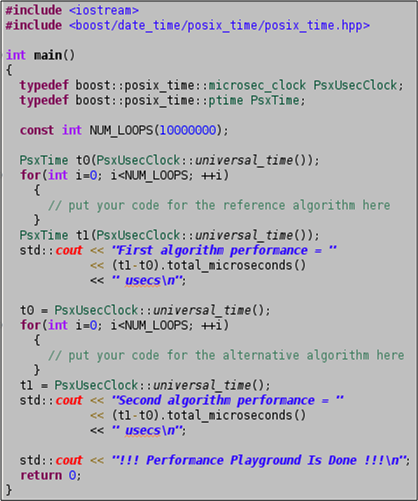

Because of the elevated importance of efficiency in real-time systems, I always keep a simple (one source code file) project named “performance_playground” open in my Eclipse IDE for algorithm/idiom/pattern prototyping and performance measurement. I use it to measure and optimize the performance of “chunks” of critical logic and to pit two or more candidates against each other in performance death matches. For each experiment I “branch” off of the project trunk and then I tag and commit the instantiation to archive the results.

The source code for the performance_playground project is shown below. The program’s sole external dependency is on the boost.date_time library for its platform-independent timestamping. Surely, you have the boost library set installed on all your development platforms, right?

How about you? Do you have something similar? Do you assume that all performance testing and algorithm vetting falls into the dreaded, time-wasting, “premature optimization” anti-pattern?

Loki Is Not Loco

Never heard of “Loki”? Check it out here: The Loki Library.

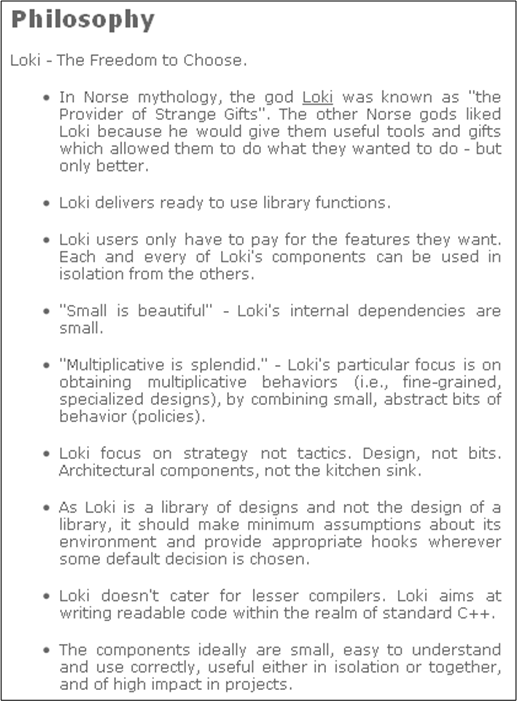

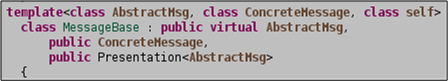

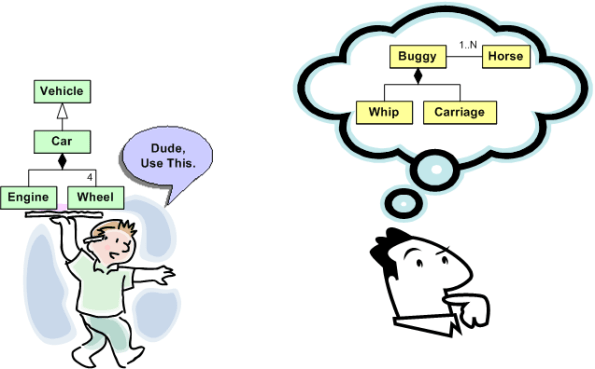

The Loki team has developed the best philosophy for programming library design that I’ve ever seen. It’s not so abstract that you can’t figure out what they mean, and they know that the real bang for the buck comes from disciplined dependency management and small, flat components. Judge for yourself:

How about you? Have you seen better?

Simply Notice…

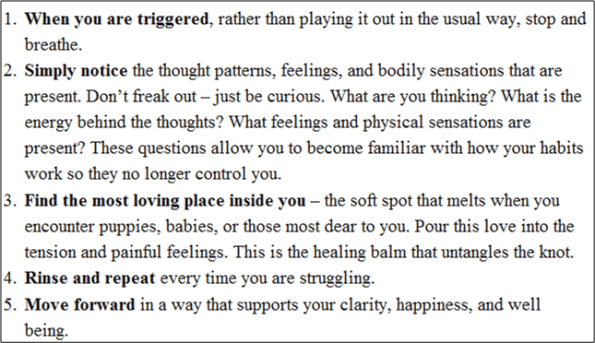

I’ve been following Leo Babauta, the creator of ZenHabits.net, for several years. Check out his inspirational story of personal transformation here: “About Leo“. In a recent Zen Habits newsletter, guest poster Gail Brenner suggested the following minimalist guide to inner peace:

This list recently came to mind while I was reading some complicated and messy library code in order to understand how to incorporate its functionality into my own code mess. Surprise! The source code was too dense and it required a deeper mental stack than the shallow one in my head, so I did what I usually do in those situations – I started getting pissed off. D’oh! Then, out of nowhere, step #2 in Gail’s list came to mind. I won’t answer the questions posed in the step, but you can imagine that they weren’t positive.

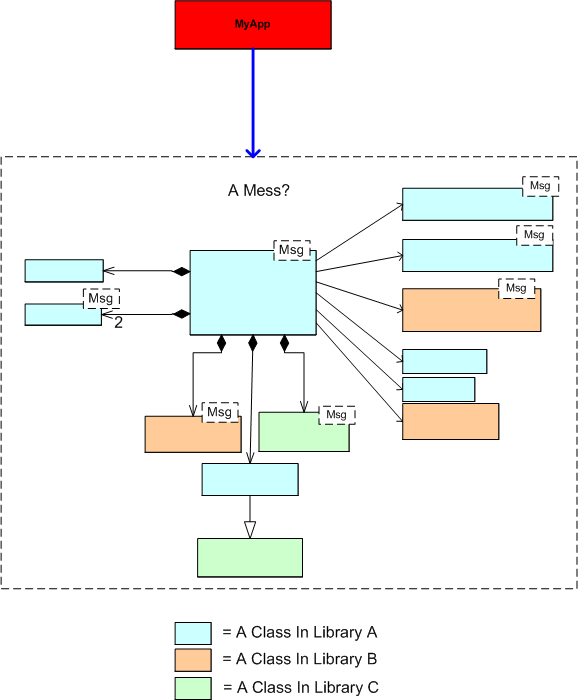

So, what did I do next? I briefly looked at step 3 and then I careened off course. I went out to stalk the library code author with the intent of ripping him/her a new one. Hah, just joking! What I really did was this. I stepped back from the hundreds of lines of source code and I reverse engineered a simpler, abstracted class diagram of the mess. By distancing myself from the code and using the more abstract class diagram to understand the code, I came to the same conclusion – it was a freakin’ mess. D’oh!

Are you wondering what my next step was? I ain’t tellin’.

Start Big?

While browsing through the “C++ FAQs“, this particular FAQ caught my eye:

The authors’ “No” answer was rather surprising to me at first because I had previously thought the answer was an obvious “Yes“. However, the rationale behind their collective “No” was compelling. Rather than butcher and fragment their answer with a cut and paste summary, I present their elegant and lucid prose as is:

Small projects, whose intellectual content can be understood by one intelligent person, build exactly the wrong skills and attitudes for success on large projects…..The experience of the industry has been that small projects succeed most often when there are a few highly intelligent people involved who use a minimum of process and are willing to rip things apart and start over when a design flaw is discovered. A small program can be desk-checked by senior people to discover many of the errors, and static type checking and const correctness on a small project can be more grief than they are worth. Bad inheritance can be fixed in many ways, including changing all the code that relied on the base class to reflect the new derived class. Breaking interfaces is not the end of the world because there aren’t that many interconnections to start with. Finally, source code control systems and formalized build procedures can slow down progress.

On the other hand, big projects require more people, which implies that the average skill level will be lower because there are only so many geniuses to start with, and they usually don’t get along with each other that well, anyway. Since the volume of code is too large for any one person to comprehend, it is imperative that processes be used to formalize and communicate the work effort and that the project be decomposed into manageable chunks. Big programs need automated help to catch programming errors, and this is where the payback for static type checking and const correctness can be significant. There is usually so much code based on the promises of base classes that there is no alternative to following proper inheritance for all the derived classes; the cost of changing everything that relied on the base class promises could be prohibitive. Breaking an interface is a major undertaking, because there are so many possible ripple effects. Source code control systems and formalized build processes are necessary to avoid the confusion that arises otherwise.

So the issue is not just that big projects are different. The approaches and attitudes to small and large projects are so diametrically opposed that success with small projects breeds habits that do not scale and can lead to failure of large projects.

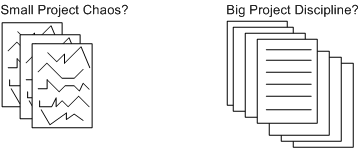

After reading this, I initially changed my previously un-investigated opinion. However, upon further reflection, a queasy feeling arose in my stomach because the implication of the authors is that the code bases on big projects aren’t as messy and undisciplined as smaller projects. Plus, it seems as though they imply that disciplined use of processes and tools have a strong correlation with a clean code base and that developers, knowing that the system will be large, will somehow change their behavior. My intuition and personal experience tell me that this may not be true, especially for large code bases that have been around for a long time and have been heavily hacked by lots of programmers (both novice and expert) under schedule pressure.

Small projects may set you up to drown later on, but big projects may start to drown you immediately. What are your thoughts, start small or big?

Static Vs Auto Performance

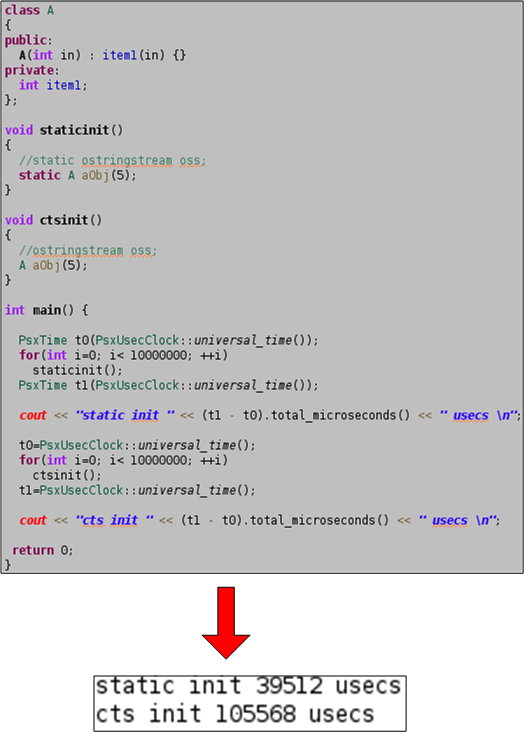

Assume that you’re writing a function that’s called every 5 milliseconds (200 Hz) in a real-time application and that thread-safety for this function is not a factor (it will be called only within one thread of control). Next, assume that you need to use one or more temporary objects to implement the logic in your function. Should you instantiate your objects as static or as auto on the stack?

Unless I’ve made a mental mistake, the source code and results below confirm that using static objects is much more efficient that using auto objects. The code measures the time it takes to instantiate 10 million static and auto objects of type std::ostringstream. The huge performance difference makes sense since the static object is only constructed during the first function call while the auto object is instantiated 10 million times.

It’s likely that std::ostringstream objects are large, but what about small, simple user types? The code below attempts to answer the question by showing that the performance difference between static and auto is still substantial for a trivial object like an instance of class A. I’ve been using this technique for years, but I’ve never quantitatively investigated the static vs auto performance difference until now.

I was motivated to perform this experiment after reading the splendid “Efficient C++“. In the book, authors Bulka and Mayhew show the results of little experiments like these for various C++ programming techniques and idioms. Unlike most classic C++ books, which sprinkle comments and insights about performance tradeoffs throughout the text, the entire book is dedicated to the topic. I highly recommend it for fledgling and intermediate C++ programmers.

We’ve All Had Those Days

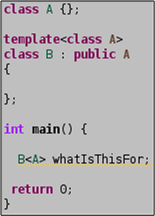

OMG! Last night, when I was sittin’ near the fire in my dinner jacket, sippin’ my glass of cognac, smokin’ my pipe, pettin’ my dog, and intently reading Sutter & Alexandrescu’s classic “C++ Coding Standards: 101 Rules, Guidelines, and Best Practices“, I came across this curious passage:

Can you remember a time when you wrote code that used the standard library (for example) and got mysterious and incomprehensible compiler errors? And you kept slightly rearranging your code and recompiling, and rearranging some more and compiling some more, until the mysterious compile errors went away, and then you happily continued on—with at best a faint nagging curiosity about why the compiler didn’t like the only-ever-so-slightly different arrangement of the code you wrote at first? We’ve all had those days…

What on earth are they talking about? That’s never happened to me. What about you?

Reinventing The Wheel

In Federico Biancuzzi’s “Masterminds Of Programming“, UML co-creator Jim Rumbaugh states:

The computing field has a lot of people that think very well of themselves and seem to forget that there is any past to build upon. A lot of people keep reinventing things that have already been discovered. – Jim Rumbaugh

LOL! I understand what Jim’s saying, but there can be another reason for reinventing the wheel too. How many slightly different API versions of virtually similar “reusable” libraries are littered around your software development org? How many of them have you written and rewritten yourself?

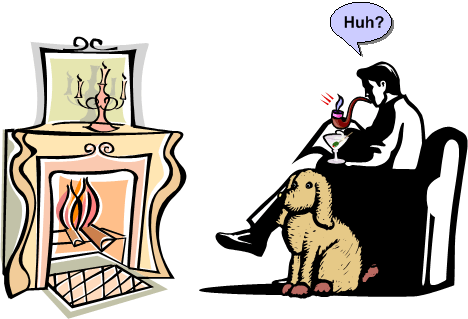

If a library/module/component is poorly or “un” documented in terms of its design, external dependencies, and most importantly, usage examples, it t’aint gonna be reused. Even if the thang IS miraculously well documented, if the info is not integrated, organized, and easily accessible, it ain’t gonna be reused either. Both of these shortcomings, which are highly likely since most programmers don’t “do documentation” and managers don’t want to pay for non-camouflage documentation, guarantee reinventing the wheel over and over again.

Assume that you truly do want to reuse someone else’s code to save time, but all you have is the source code. You’re gonna have to pour through the mess to figure out what it offers, how it works, and what other components and libraries it depends on before you can consider using it “as is“. The larger and denser the component, the deeper and wider the inheritance tree, the more external dependencies, the more frustrated you’ll become and the less likely you’ll apply your brainpower and time to the task at hand. When that happens, Ta Dah, it’s time to roll your own – yet again. Hell, if you don’t document your own stuff, you might not even be able to eat your own dog food downstream. D’oh! I hate when that happens. And yes, it happens to me.