Archive

Fat, Lazy, Slob Who Did Good

Kevin Smith’s “Tough Sh*t: Life Advice from a Fat, Lazy Slob Who Did Good” is the first lite and breezy book that I’ve read in quite a while.

In between exercise sets at the gym, I scribbled down a quick review of the book. In keeping with the lazy slob theme, I didn’t transcribe the scribbles into e-form. So, here’s the review in raw and unedited form:

While prepping this post for publication, I got a kick out of the list of tags that wordpress.com recommended :

The “Shit” and “Clerks” tags were good calls, but freakin’ Condoleezza Rice????? I gotta have a word with the dude behind the curtain who patiently types in tag recommendations each time a draft is saved.

All Forked Up!

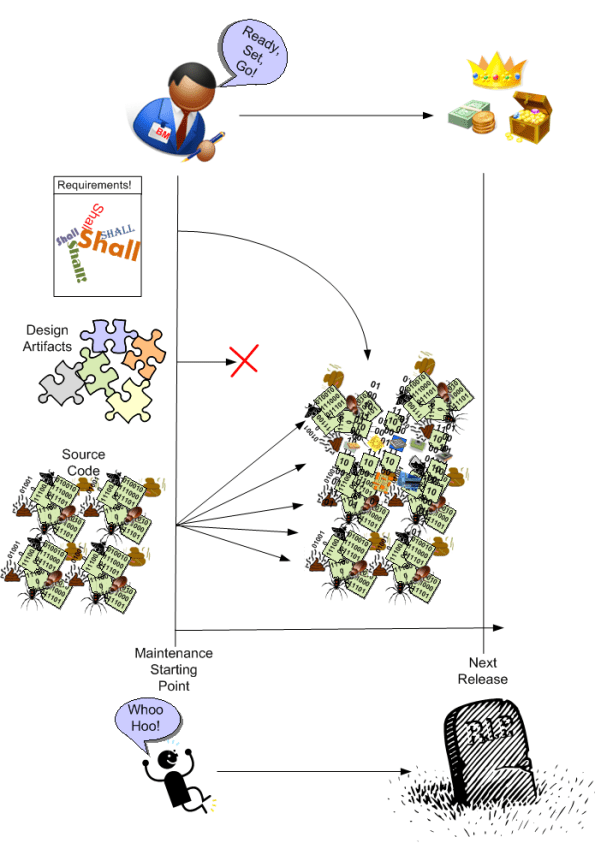

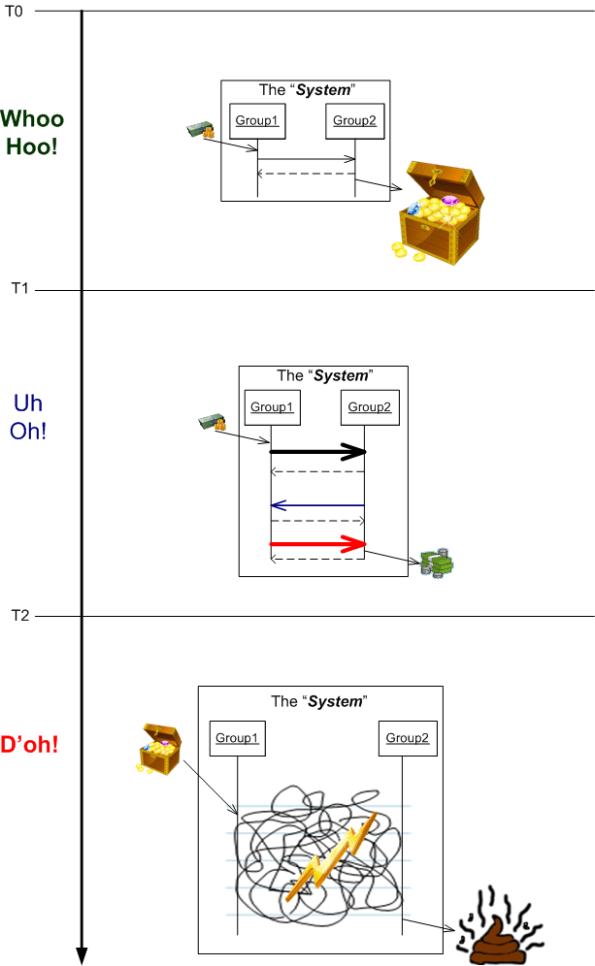

BD00 posits that many software development orgs start out with good business intentions to build and share a domain-specific “platform” (a.k.a. infrastructure) layer of software amongst a portfolio of closely related, but slightly different instantiations of revenue generating applications. However, as your intuition may be hinting at, the vast majority of these poor souls unintentionally, but surely, fork it all up. D’oh!

The example timeline below exposes just one way in which these colossal “fork ups” manifest. At T0, the platform team starts building the infrastructure code (common functionality such as inter-component communication protocols, event logging, data recording, system fault detection/handling, etc) in cohabitation with the team of the first revenue generating app. It’s important to have two loosely-coupled teams in action so that the platform stays generic and doesn’t get fused/baked together with the initial app product.

At T1, a new development effort starts on App2. The freshly formed App2 team saves a bunch of development cost and time upfront by reusing, as-is, the “general” platform code that’s being co-evolved with App1.

Everything moves along in parallel, hunky dory fashion until something strange happens. At T2, the App2 product team notices that each successive platform update breaks their code. They also notice that their feature requests and bug reports are taking a back seat to the App1 team’s needs. Because of this lack of “service“, at T3 the frustrated App2 team says “FORK IT!” – and they literally do it. They “clone and own” the so-called common platform code base and start evolving their “forked up” version themselves. Since the App2 team now has to evolve both their App and their newly born platform layer, their schedule starts slipping more than usual and their prescriptive “plan” gets more disconnected from reality than it normally does. To add insult to injury, the App2 team finds that there is no usable platform API documentation, no tutorial/example code, and they must pour through 1000s of lines of code to figure out how to use, debug, and add features to the dang thing. Development of the platform starts taking more time than the development of their App and… yada, yada, yada. You can write the rest of the story, no?

So, assume that you’ve been burned once (and hopefully only once) by the ubiquitous and pervasive “forked up” pattern of reuse. How do you prevent history from repeating itself (yet again)? Do you issue coercive threats to conform to the mission? Do you swap out individuals or whole teams? Do you send your whole org to a 3 day Scrum certification class? Will continuous exhortations from the heavens work to change “mindsets“? Do you start measuring/collecting/evaluating some new metrics? Do you change the structure and behaviors of the enclosing social system? Is this solely a social problem; solely a technical problem? Do you not think about it and hope for the best – the next time around?

Ready, Set, Go!

Risk-Reward Curve

I’d like to thank my new found e-friend Bob Marshall for triggering the creation of this scientifically unassailable graph:

Thinking Styles

I used to think: “DAMN IT! IT SHOULDN’T BE THIS WAY!” for just about every observation that I judged to be a “problem“. Now I think, “It shouldn’t be this way – but it is – lol“ for most observations that I judge to be problems. Of course, there are still far too many things that cause me to red-line, but it’s an incremental, iterative, and continuous learning experience.

If I’m lucky enough, I might even gravitate up to this fully, non-judgmental, thought-style: “It is this way, because it got this way“. However, I don’t think I’ll ever make it into the effortless thinking realm of Buddha/Lao Tzu/Eckhart Tolle/Byron Katy: “It is this way because it’s exactly the way it should be“.

How about you, dear reader? What’s your predominant thinking style? Has it been changing with age? Are you happy with it?

Protocol Deterioration

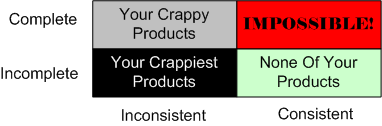

Russ Ackoff once said something like: “A system is not the sum of its parts. It’s the product of its part-interactions“. With that Ackoffism in mind, lo and behold the slooow and relentless process of inter-part protocol deterioration.

What state are your org protocols in? “Whoo Hoo!“, “Uh Oh!“, “D’oh!“, or “I Dunno!“?

Value And Effectiveness

A few weeks ago, my friend Charlie Alfred challenged me to take a break from railing against the dysfunctional behaviors that “emerge” from the vertical command and control nature of hierarchies. He suggested that I go “horizontal“. Well, I haven’t answered his challenge, but Charlie came through with this wonderful guest post on that very subject. I hope you enjoy reading Charlie’s insights on the horizontal communication gaps that appear between specialized silos as a result of corpo growth. Please stop by his blog when you get a chance.

——————————————————————————————————————————–

In “Profound Shift in Focus“, BD00 discusses the evolution of value-focused startups into cost-focused borgs. There’s ample evidence for this, but one wonders what lies at the root?

One clue is Russell Ackoff’s writings on analysis and synthesis. Analysis starts with a system and takes it apart, in the pursuit of understanding how it works. Synthesis, starts with a system, identifies the systems which contain it, and studies the role of the original system within its containing systems in the pursuit of understanding why it must work that way.

Analytical thinking is the engine that powered the Industrial Revolution and many of the most important scientific advances of the 21st century. Understanding how things work is essential to making them work better (also known as efficiency). Today, we have better automobiles, airplanes, computers, phones, and TV’s than our parents. And we owe much of this to analytical thinking.

But one of the side effects of analytical thinking is specialization. As understanding deepens, the volume of subject matter knowledge explodes. This leads to the old joke.

Q: What’s the difference between an engineer and an executive?

A: Every day engineers learn more and more about less and less, until one day they know everything about nothing, while executives learns less and less about more and more, until one day they know nothing about everything.

But all joking aside, this is a serious concern. The vast majority of organizations today are organized functionally: sales, marketing, finance, engineering, manufacturing, HR, IT, etc. And withing these organizations, there are even more specializations. Marketing has specialists in advertising, public relations, research, distribution channels, and product management. Engineering has chemical, mechanical, electrical, firmware, and software engineers. Even in software development, you have specialists in user interfaces, networking, databases. realtime embedded and project management.

One of the critical problems is that most people working in each of these areas become overspecialized. They spend so much time accumulating and applying specialized knowledge, that they can only communicate with people in their own specialty. If you don’t believe me, observe a two hour meeting involving somebody from sales, market research, product management, mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, finance, and purchasing.

In Mythical Man Month, Frederick Brooks retells the Tower of Babel as a project management story. It fits perfectly, because the root cause of the Tower of Babel failure was overspecialization and a failure to communicate. Today, instead of talking Hebrew, Arabic, Persian and Greek, we talk gross margin, differentiation, segmentation, tensile strength, electromagnetic interference, and virtual inheritance.

And our communication has another quality. Solution focus. We routinely argue the flaws and merits of solutions with only the foggiest understanding of what the problem is. And we use the vast levels of specialized knowledge from our respective disciplines to shout down the cretans who disagree with us.

Cost reduction and efficiency live in the same neighborhood as specialization and analytical thinking:

- If we replace these two steps with this one, the process will be faster.

- If we replace this part with this other part, the unit cost will be reduced by 2%.

- If we consolidate these three models into one, we can reduce inventory by 20%.

If efficiency is “doing things the right way”, then effectiveness is “doing the right things the right way.” Value lives next door to effectiveness and both live in the same neighborhood as synthesis. Value, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. Products and services can deliver benefits, but only the buyers and users can apply these benefits to realize value. Consider smartphones. Some people only use their phones for mobile calls, others for text messaging, some to read books on the train.

So in the end, there are a couple of reasons that startups are inherently focused on value. First, because they are small, specialization is a liability. Most people in startups do several jobs (well), by necessity. Second, because they are not yet profitable and self-sustaining, their survival is highly dependent on their surroundings (e.g. customers, competitors, economic conditions). This requires more synthesis than analysis.

As they grow, their strategy shifts to cost. Michael Porter writes about this in Competitive Advantage. And guess what, every one of us bargain-hunting, coupon-clipping, “buy one get one free” consumers is the root cause of this. Why mention this? Because synthetic thinkers love systems with feedback loops!

Profound Shift In Focus

The following quote comes from John Hagel via this Peter Vander Auwera blog post: “Corporate Rebels United” – the start of a corporate spring?”:

The key answer that defines the post-digital enterprise is to shift attention from the cost side to the value side. Rather than treating employees as cost items that need to be managed wherever possible, why not view them as assets capable of delivering ever-increasing value to the marketplace? This is a profound shift in focus. For one thing, it moves us from a game of diminishing returns to an opportunity for increasing returns. There is little, if any, limit to the additional value that people can deliver if given the appropriate tools and skill development. – John Hagel

For big, established companies who can’t even remember what it was like to focus on value, “profoundly shifting” from a cost mindset back to a value mindset is a tall order indeed.

As the state machine based figure below illustrates, successful startups are totally “value focused” in the sun-up phase of their life. But over time, as they obsessively grow and misguidedly try to become more efficient by adding layers upon layers of cost watchers, the vast majority of them (with few Apple-like exceptions) morph into “cost focused” borgs.

Once a formerly vibrant org has moved into the sundown phase of its life, the borgdom hardens. It’s cost-focus till death, with no memory of any prior, value-focused behavior.

Incomplete AND Inconsistent

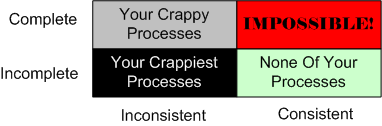

In the early 1900s, Bertrand Russell and Alfred Whitehead published their seminal work, “Principia Mathematica“. Its purpose was to “derive all of mathematics from purely logical axioms” and many smart minds thought they pulled off this Herculean task. However, Kurt Godel came along and busted up the party by throwing a turd in the punch bowl with his blockbuster incompleteness theorem. The incompleteness theorem essentially states that no system of logic can be both consistent and complete. One or the other, but not both.

So, let’s apply Godel’s findings to “logical“, software-intensive systems:

Next, let’s apply the incompleteness theorem to “logical” management systems:

Me thinks that Mr. Spock, one of my all time heroes because of his calm, cool, and collected demeanor and logical genius, was wrong – at least some of the time. Damn that Kurt Godel!

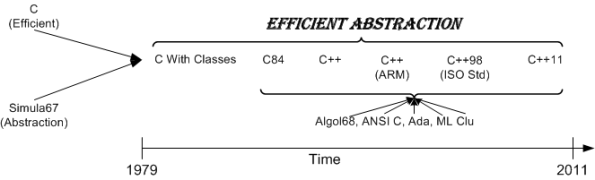

Efficient Abstraction

In “The Design And Evolution Of C++“, Bjarne Stroustrup presents a tree-like picture on the history of programming languages and how they’ve influenced each other. For your studying pleasure, BD00 surgically extracted and augmented a slightly more C++ focused sub-tree. In other words, BD00 committed yet another act of plagiarism. I hope you like the result.

All through the 30+ years of C++’s evolution, Bjarne and the ISO C++ standards committee have maintained a fierce and agonizing determination to march to the tune of “efficient abstraction” over theoretical purity. Adding increasing support for abstraction without sacrificing much in efficiency is more of an art than science.

D&E is not just a history book. As the figure below shows, it won one of the “Software Development Productivity Awards” from Software Development magazine waaay back when. That’s because knowing “why” and “how” the (or any) language became the way it is gives a qualitative edge to those programmers over those who just know “what” the language is.