Archive

Hopping On The Anti-Fragile Bandwagon

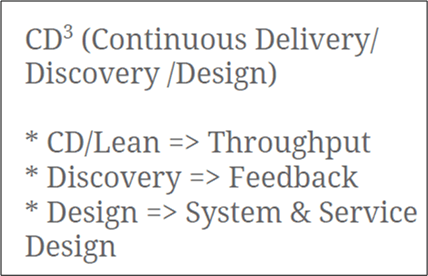

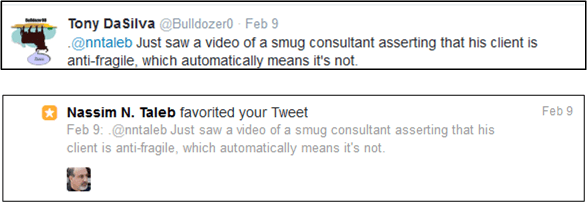

Since Martin Fowler works there, I thought ThoughtWorks Inc. must be great. However, after watching two of his fellow ThoughtWorkers give a talk titled “From Agility To Anti-Fragility“, I’m having second thoughts. The video was a relatively lame attempt to jam-fit Nassim Taleb’s authentic ideas on anti-fragility into the software development process. Expectedly, near the end of the talk the presenters introduced their “new” process for making your borg anti-fragile: “Continuous Delivery/Discovery/Design“. Lookie here, it even has a superscript in its title:

Having read Mr. Taleb’s four fascinating books, the one hour and twenty-six minute talk was essentially a synopsis of his latest book, “Anti-Fragile“. That was the good part. The ThoughtWorkers’ attempts to concoct techniques that supposedly add anti-fragility to the software development process introduced nothing new. They simply interlaced a few crummy slides with well-known agile practices (small teams, no specialists, short increments, co-located teams, etc) with the good slides explaining optionality, black/grey swans, convexity vs concavity, hormesis, and levels of randomness.

Understood, Manageable, And Known.

Our sophistication continuously puts us ahead of ourselves, creating things we are less and less capable of understanding – Nassim Taleb

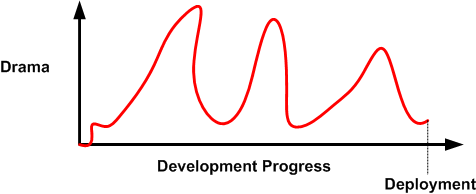

It’s like clockwork. At some time downstream, just about every major weapons system development program runs into cost, schedule, and/or technical performance problems – often all three at once (D’oh!).

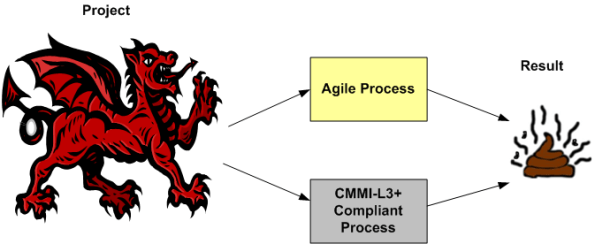

Despite what their champions espouse, agile and/or level 3+ CMMI-compliant processes are no match for these beasts. We simply don’t have the know how (yet?) to build them efficiently. The scope and complexity of these Leviathans overwhelms the puny methods used to build them. Pithy agile tenets like “no specialists“, “co-located team“, “no titles – we’re all developers” are simply non-applicable in huge, multi-org programs with hundreds of players.

Being a student of big, distributed system development, I try to learn as much about the subject as I can from books, articles, news reports, and personal experience. Thanks to Twitter mate @Riczwest, the most recent troubled weapons system program that Ive discovered is the F-35 stealth fighter jet. On one side, an independent, outside-of-the-system, evaluator concludes:

The latest report by the Pentagon’s chief weapons tester, Michael Gilmore, provides a detailed critique of the F-35’s technical challenges, and focuses heavily on what it calls the “unacceptable” performance of the plane’s software… the aircraft is proving less reliable and harder to maintain than expected, and remains vulnerable to propellant fires sparked by missile strikes.

On the other side of the fence, we have the $392 billion program’s funding steward (the Air Force) and contractor (Lockheed Martin) performing damage control via the classic “we’ve got it under control” spiel:

Of course, we recognize risks still exist in the program, but they are understood and manageable. – Air Force Lieutenant General Chris Bogdan, the Pentagon’s F-35 program chief

The challenges identified are known items and the normal discoveries found in a test program of this size and complexity. – Lockheed spokesman Michael Rein

All of the risks and challenges are understood, manageable, known? WTF! Well, at least Mr. Rein got the “normal” part right.

In spite of all the drama that takes place throughout a large system development program, many (most?) of these big ticket systems do eventually get deployed and they end up serving their users well. It simply takes way more sweat, time, and money than originally estimated to get it done.

All Forked Up

I dunno who said it, but paraphrasing whoever did:

Science progresses as a succession of funerals.

Even though more accurate and realistic models that characterize the behavior of mass and energy are continuously being discovered, the only way the older physics models die out is when their adherents kick the bucket.

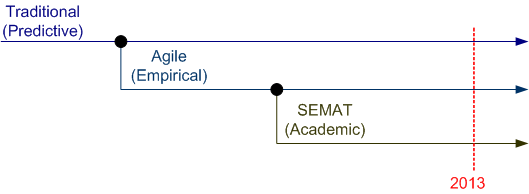

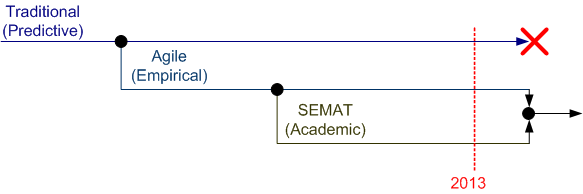

The same dictum holds true for software development methodologies. In the beginning, there was the Traditional (a.k.a waterfall) methodology and its formally codified variations (RUP, MIL-STD-498, CMMI-DEV, your org’s process, etc). Next, came the Agile fork as a revolutionary backlash against the inhumanity inherent to the traditional way of doing things.

The most recent fork in the methodology march is the cerebral SEMAT (Software Engineering Method And Theory) movement. SEMAT can be interpreted (perhaps wrongly) as a counter-revolution against the success of Agile by scorned, closet traditionalists looking to regain power from the agilistas.

On the other hand, perhaps the Agile and SEMAT camps will form an alliance and put the final nail in the coffin of the old traditional way of doing things before its adherents kick the bucket.

SEMAT co-creator Ivar Jacobson seems to think that hitching SEMAT to the Agile gravy train holds promise for better and faster software development techniques.

SEMAT co-creator Ivar Jacobson seems to think that hitching SEMAT to the Agile gravy train holds promise for better and faster software development techniques.

Who knows what the future holds? Is another, or should I say, “the next“, fork in the offing?

PLAN MORE!

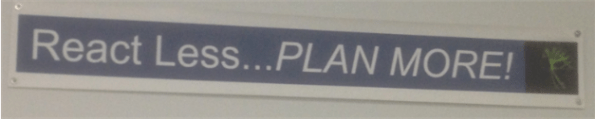

Check out this 20th century retro banner that BD00 stumbled upon whilst being given a tour of a friend’s new workplace:

OMG! The smug agilista community would be outraged at such a bold, blasphemous stunt! But you know what? BD00’s friend’s org is alive and well. It’s making money, the future looks bright for the business, and the people who work there seem to be content. Put that in your pipe and stoke it up.

A Concrete Agile Practices List

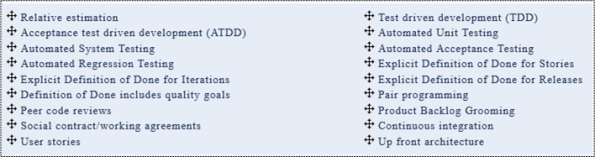

Finally, I found out what someone actually thinks “agile practices” are. In “What are the Most Important and Adoption-Ready Agile Practices?”, Shane-Hastie presents his list:

Kudos to Shane for putting his list out there.

Ya gotta love all the “explicit definition of done” entries (“Aren’t you freakin’ done yet?“). And WTF is “Up front architecture” doing on the list? Isn’t that a no-no in agile-land? Shouldn’t it be “emergent architecture“? And no kanban board entry? What about burn down charts?

Alas, I can’t bulldozify Shane’s list too much. After all, I haven’t exposed my own agile practices list for scrutiny. If I get the itch, maybe I’ll do so. What’s on your list?

The Magical Number 30

In agile processes, especially Scrum, 30 is a magical number. A working product increment should never take more than 30 days to produce. The reasoning, which is sound, is that you’ll know exactly what state the evolving product is in quicker than you normally would under a “traditional” process. You can then decide what to do next before expending more resources.

The trouble I have with this 30 day “law” is that not all requirements/user-stories/function-points/”shalls” are created equal. Getting from a requirement to tested, reviewed, integrated, working code may take much longer – especially for big, distributed systems or algorithmically dense components.

Arbitrarily capping delivery dates to a maximum of 30 days and mandating deliveries to be rigidly periodic is simply a marketing ploy and an executive attention grabber. When managers and executives accustomed to many man-months between deliveries get a whiff of the “30 day” guarantee, they: make a beeline to the nearest agile cathedral; gleefully kneel at the altar; and line up their dixie cups for the next round of kool-aid.

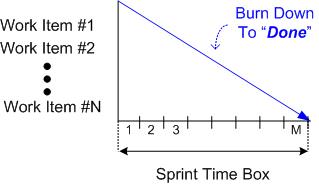

Burn Baby Burn

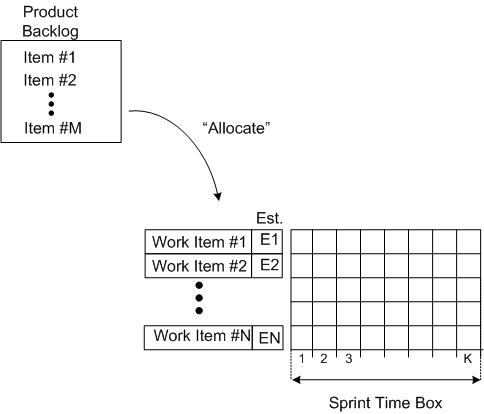

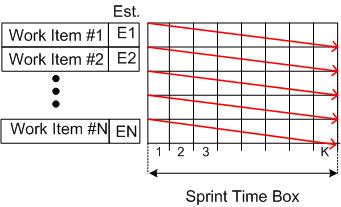

The “time-boxed sprint” is one of the star features of the Scrum product development process framework. During each sprint planning meeting, the team estimates how much work from the product backlog can be accomplished within a fixed amount of time, say, 2 or 4 weeks. The team then proceeds to do the work and subsequently demonstrate the results it has achieved at the end of the sprint.

As a fine means of monitoring/controlling the work done while a sprint is in progress, some teams use an incarnation of a Burn Down Chart (BDC). The BDC records the backlog items on the ordinate axis, time on the abscissa axis, and progress within the chart area.

The figure below shows the state of a BDC just prior to commencing a sprint. A set of product backlog items have been somehow allocated to the sprint and the “time to complete” each work item has been estimated (Est. E1, E2….).

At the end of the sprint, all of the tasks should have magically burned down to zero and the BDC should look like this:

So, other than the shortened time frame, what’s the difference between an “agile” BDC and the hated, waterfall-esque, Gannt chart? Also, how is managing by burn down progress any different than the hated, traditional, Earned Value Management (EVM) system?

So, other than the shortened time frame, what’s the difference between an “agile” BDC and the hated, waterfall-esque, Gannt chart? Also, how is managing by burn down progress any different than the hated, traditional, Earned Value Management (EVM) system?

I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by – Douglas Adams

In practice, which of the outcomes below would you expect to see most, if not all, of the time? Why?

We need to estimate how many people we need, how much time, and how much money. Then we’ll know when we’re running late and we can, um, do something.

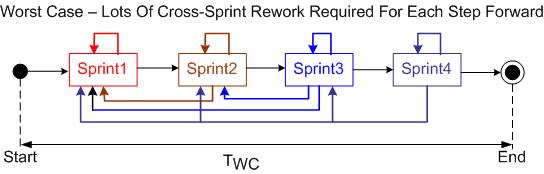

One Step Forward, N-1 Steps Back

For the purpose of entertainment, let’s assume that the following 3-component system has been deployed and is humming along providing value to its users:

Next, assume that a 4-sprint enhancement project that brought our enhanced system into being has been completed. During the multi-sprint effort, several features were added to the system:

OK, now that the system has been enhanced, let’s say that we’re kicking back and doing our project post-mortem. Let’s look at two opposite cases: the Ideal Case (IC) and the Worst Case (WC).

First, the IC:

During the IC:

- we “embraced” change during each work-sprint,

- we made mistakes, acknowledged and fixed them in real-time (the intra-sprint feedback loops),

- the work of Sprint X fed seamlessly into Sprint X+1.

Next, let’s look at what happened during the WC:

Like the IC, during each WC work-sprint:

- we “embraced” change during each work-sprint,

- we made mistakes, acknowledged and fixed them in real-time (the intra and inter-sprint feedback loops),

- the work of Sprint X fed seamlessly into Sprint X+1.

Comparing the IC and WC figures, we see that the latter was characterized by many inter-sprint feedback loops. For each step forward there were N-1 steps backward. Thus, TWC >> TIC and $WC >> $IC.

WTF? Why were there so many inter-sprint feedback loops? Was it because the feature set was ill-defined? Was it because the in-place architecture of the legacy system was too brittle? Was it because of scope creep? Was it because of team-incompetence and/or inexperience? Was it because of management pressure to keep increasing “velocity” – causing the team to cut corners and find out later that they needed to go back often and round those corners off?

So, WTF is the point of this discontinuous, rambling post? I dunno. As always, I like to make up shit as I go.

After-the-fact, I guess the point can be that the same successes or dysfunctions can happen during the execution of an agile project or during the execution of a project executed as a series of “mini-waterfalls“:

- ill-defined requirements/features/user-stories/function-points/use-cases (whatever you want to call them)

- working with a brittle, legacy, BBOM

- team incompetence/inexperience

- scope creep

- schedule pressure

Ultimately, the forces of dysfunction and success are universal. They’re independent of methodology.

Agile Overload

Since I buy a lot of Kindle e-books, Amazon sends me book recommendations all the time. Check out this slew of recently suggested books:

My fave in the list is “Agile In A Flash“. I’d venture that it’s written for the ultra-busy manager on-the-go who can become an agile expert in a few hours if he/she would only buy and read the book. What’s next? Agile Cliff notes?

“Agile” software development has a lot going for it. With its focus on the human-side of development, rapid feedback control loops to remove defects early, and its spirit of intra-team trust, I can think of no better way to develop software-intensive systems. It blows away the old, project-manager-is-king, mechanistic, process-heavy, and untrustful way of “controlling” projects.

However, the word “agile” has become so overloaded (like the word “system“) that….

Everyone is doing agile these days, even those that aren’t – Scott Ambler

Gawd. I’m so fed up with being inundated with “agile” propaganda that I can’t wait for the next big silver bullet to knock it off the throne – as long as the new king isn’t centered around the recently born, fledgling, SEMAT movement.

What about you, dear reader? Do you wish that the software development industry would move on to the next big thingy so we can get giddily excited all over again?

Alternative Considerations

Before you unquestioningly accept the gospel of the “evolutionary architecture” and “emergent design” priesthood, please at least pause to consider these admonitions:

Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe – Abe Lincoln

Measure twice, cut once – Unknown

If I had an hour to save the world, I would spend 59 minutes defining the problem and one minute finding solutions – Albert Einstein

100% test coverage is insufficient. 35% of the faults are missing logic paths – Robert Glass