Archive

He Said, He Thought, He Said, He Thought

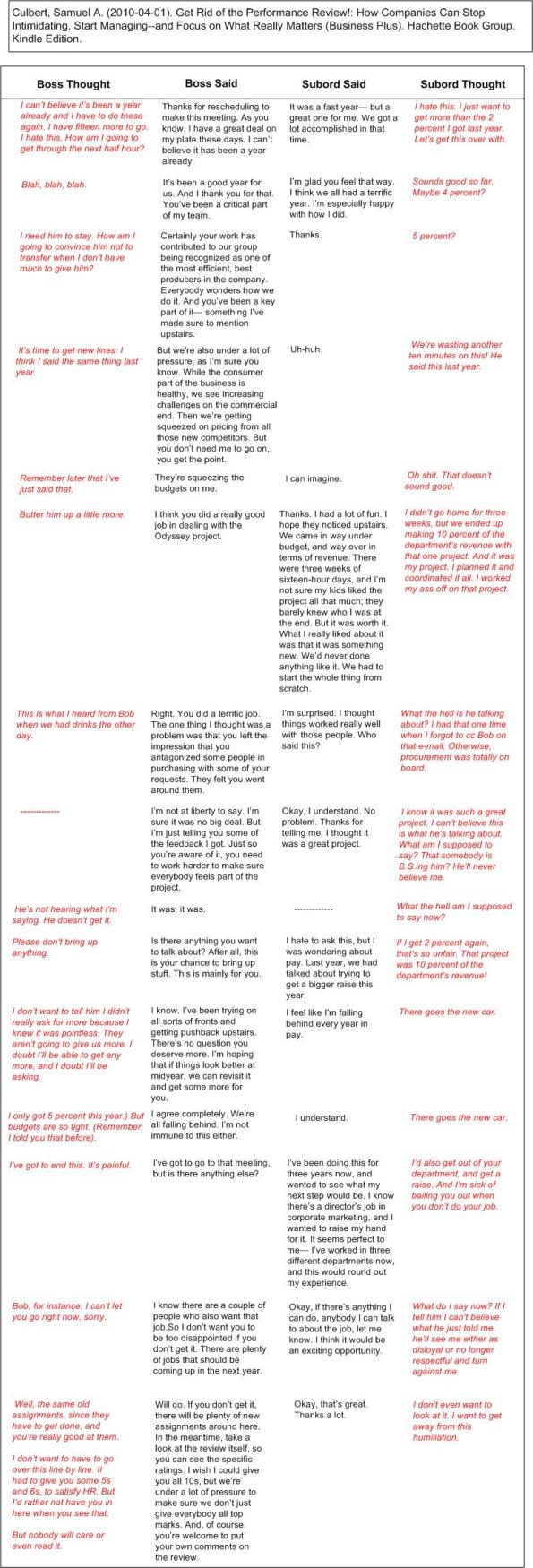

In “Get Rid of the Performance Review!: How Companies Can Stop Intimidating, Start Managing–and Focus on What Really Matters“, Sam Culbert provides several, made-up, boss-subordinate exchanges to make his case for jettisoning the archaic, 1900’s “annual performance review“. For your reading pleasure, I lifted one of these depressingly funny exchanges out of the book and transformed it into a derivation of Chris Argyris’s terrific LHS-RHS format. It’s long, and it took me a bazillion years to recreate it on this stupid-arse blawg; so please read the freakin’ thing.

Did you notice how both the boss and the subordinate suffered from the ordeal? But of course, you don’t have to worry about experiencing similar torture because the “annual performance review” at your institution is different. Even better, your org has moved into the 21st century by implementing an alternative, more equitable and civilized way of gauging performance and giving raises.

In his hard-hitting and straight-talking book, Mr. Culbert, a UCLA management school professor and industry consultant firebrand (he’s got street cred!), really skewers C-level management. He fires his most devastating salvos at evil HR departments for sustaining the “annual performance review” disaster that sucks the motivation out of everybody within reach. And yes, he does provide viable alternatives (that won’t ever be implemented in established, status-quo-loving borgs) to HR’s beloved “annual performance review“. Buy and read the book to find out what they are.

Note: Thanks Elisabeth, for steering me toward Mr. Culbert’s blasphemous work. It has helped to reinforce my entrenched UCB and the self-righteous illusion that “I’m 100% right“. But wait! I’m not allowed to be right.

Non-Compliance

Courageous Journey

Here’s a dare fer ya:

If your org has a long, illustrious history of product development and you’re just getting started on a new, grand effort that will conquer the world and catapult you and your clan to fame and fortune, ask around for the post-mortem artifacts documenting those past successes.

If by some divine intervention, you actually do discover a stash of post-mortems stored on the 360 KB, 3.5 inch floppy disk that comprises your org’s persistent memory, your next death-defying task is to secure access to the booty.

If by a second act of gawd you’re allowed to access the “data“, then pour through the gobbledygook and look for any non-bogus recommendations for future improvement that may be useful to your impending disaster, err, I mean, project. Finally, ask around to discover if any vaunted org processes/procedures/practices were changed as a result of the “lessons learned” from innocently made bad decisions, mistakes, and errors.

But wait, you’re not 100% done! If you do survive the suicide mission with your bowels in place and title intact, you must report your findings back here. To celebrate your courageous journey through Jurassic Park, there may be a free BD00 T-shirt in the offing. Making stuff up is unacceptable – BD00 requires verifiable data and three confirmatory references. Only BD00 is “approved” to concoct crap, both literally and visually, on this dumbass and reputation-busting blawg.

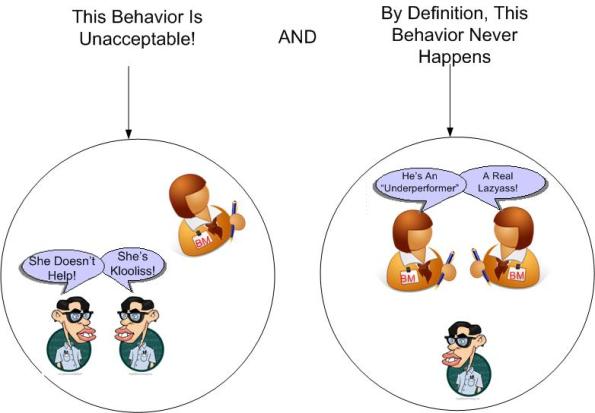

Behind One’s Back

Most reasonable people think that “talking behind one’s back” is a dishonorable and disrespectful thing to do. But aren’t many corpo performance evaluation systems designed, perhaps inadvertently, to do just that?

In some so-called performance evaluation systems, an “authorized” evaluator (manager) talks to an evaluatee’s peers to get the “real scoop” on the behavior, oops, I mean the “performance” of the evaluatee. But can’t that be interpreted (by unreasonable people, of course) as a sanctioned form of talking behind one’s back?

In these ubiquitously pervasive and taken-for-granted performance evaluation systems, when the covert, behind-the-back, intelligence gathering is complete and an “objective” judgment is concocted, it’s bestowed upon the evaluatee at the yearly, formal, face-to-face get together.

Wouldn’t it be more open, transparent, and noble to require face-to-face, peer-to-peer reviews before the dreaded “sitdown” with Don Corleone? Even better, wouldn’t it be cool if the evaluatee was authorized by the head shed to evaluate the evaluator?

“Mr. Corleone, just about every action you took last year slowed me down, dampened my intrinsic motivation, and delayed my progess. Hence, you sucked and you need to improve your performance over the next year.“

But alas, hierarchies aren’t designed for equity. Besides, quid pro quo collaboration takes too much time and we all know time is money. Chop, chop, get back to work!

To make the situation more inequitable and more “undiscussable“, some orgs institute two performance evaluation systems: the formal one described above for the brain dead DICsters down in the bilge room; and the undocumented, unpublicized, and supposedly unknown one for elite insiders.

If you work in an org that has a patronizing, behind-your-back performance evaluation system, don’t even think of broaching the subject to those who have the power to change the system. As Chris Argyris has stated many times, discussing undiscussables is undiscussable.

But wait! Snap out of that psychedelic funk you may have found yourself drifting into after reading the above blasphemy. Remember whose freakin’ blog you’re reading. It’s BD00’s blog – the self-proclaimed, mad, l’artiste.

Don’t Do This!

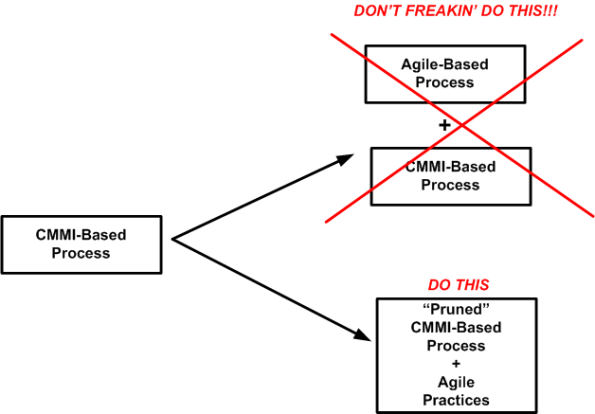

Because of its oxymoronic title, I started reading Paul McMahon’s “Integrating CMMI and Agile Development: Case Studies and Proven Techniques for Faster Performance Improvement“. For CMMI compliant orgs (Level >= 3) that wish to operate with more agility, Paul warns about the “pile it on” syndrome:

So, you say “No org in their right mind would ever do that“. In response, BD00 sez “Orgs don’t have minds“.

Yin And Yang

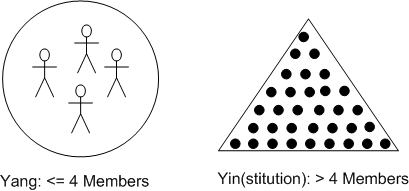

In Bill Livingston’s current incarnation of the D4P, the author distinguishes between two mutually exclusive types of orgs. For convenience of understanding, Bill arbitrarily labels them as Yin (short for “Yinstitution“) and Yang (short for “Yang Gang“):

The critical number of “four” in Livingston’s thesis is called “the Starkermann bright line“. It’s based on decades of modeling and simulation of Starkermann’s control-theory-based approach to social unit behavior. According to the results, a group with greater than 4 members, when in a “mismatch” situation where Business As Usual (BAU) doesn’t apply to a novel problem that threatens the viability of the institution, is not so “bright” – despite what the patriarchs in the head shed espouse. Yinstitutions, in order to retain their identities, must, as dictated by natural laws (control theory, the 2nd law of thermodynamics, etc), be structured hierarchically and obey an ideology of “infallibility” over “intelligence” as their ideological MoA (Mechanism of Action).

According to Mr. Livingston, there is no such thing as a “mismatch” situation for a group of <= 4 capable members because they are unencumbered by a hierarchical class system. Yang Gangs don’t care about “impeccable identities” and thus, they expend no energy promoting or defending themselves as “infallible“. A Yang Gang’s structure is flat and its MoA is “intelligence rules, infallibility be damned“.

The accrual of intelligence, defined by Ross Ashby as simply “appropriate selection“, requires knowledge-building through modeling and rapid run-break-learn-fix simulation (RBLF). Yinstitutions don’t do RBLF because it requires humility, and the “L” part of the process is forbidden. After all, if one is infallible, there is no need to learn.

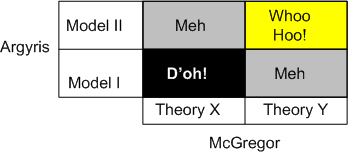

1, 2, X, Y

Chris Argyris has his Model 1 and Model 2 theories of action:

- Model I: The objectives of this theory of action are to: (1) be in unilateral control; (2) win and do not lose; (3) suppress negative feelings; and (4) behave rationally.

- Model II: The objectives of this theory of action are to: (1) seek valid (testable) information; (2) create informed choice; and (3) monitor vigilantly to detect and correct error.

Douglas McGregor has his X and Y theories of motivation:

- Theory X: Employees are inherently lazy and will avoid work if they can and that they inherently dislike work.

- Theory Y: Employees may be ambitious and self-motivated and exercise self-control; they enjoy their mental and physical work duties.

Let’s do an Argyris-McGregor mashup and see what types of enterprises emerge:

Snapback To “Business As Usual”

Over the years, I’ve read quite a few terrific and insightful reports from the General Accountability Office (GAO) on the state of several big, software-intensive, government programs. The GAO is the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of the US Congress. Its mission is to:

help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. The GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions.

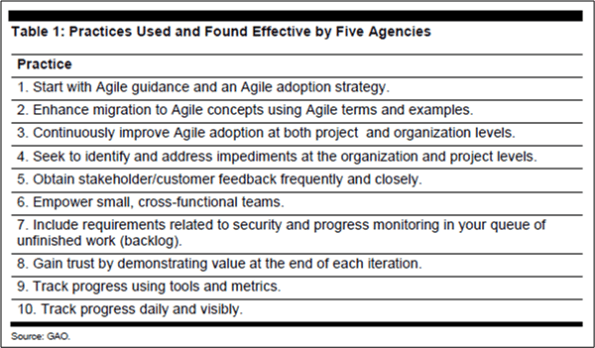

In a newly released report titled “Software Development: Effective Practices And Federal Challenges In Applying Agile Methods“, the GAO communicated the results of a study it performed on the success of using “agile” software methods in five agencies (a.k.a. bureaucracies): the Department of Commerce, Defense, Veterans Affairs, the Internal Revenue Service, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

The GAO report deems these 10 best practices as effective for taking an agile approach:

Yawn. Every time I read a high-falutin’ list like this, I’m hauntingly reminded of what Chris Argyris essentially says:

Most advice given by “gurus” today is so abstract as to be un-actionable.

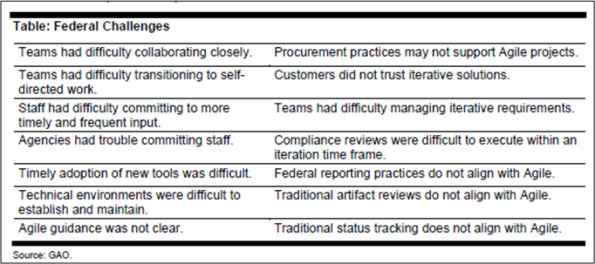

The GAO report also found more than a dozen challenges with the agile approach for federal agencies:

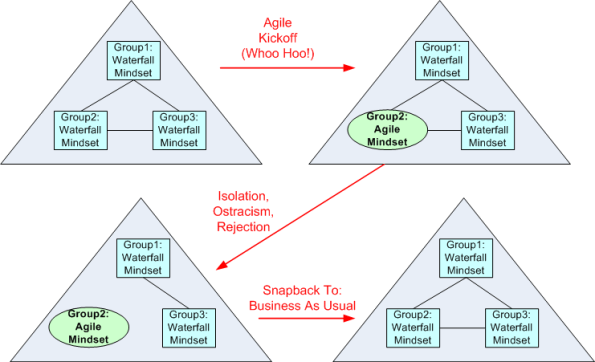

Again, yawn. These are not only federal challenges…. they’re HUGE commercial challenges as well. When the whole borg infrastructure, its policies, its protocols, its (planning, execution, reporting) procedures, and most importantly, its sub-group mindsets are steadfastly waterfall-dominated, here’s what usually happens when “agile” is attempted by a courageous borg sub-group:

D’oh! I hate when that happens.

OMITTED ACTIVITIES!

The best book I’ve read (so far) on software estimation is Steve McConnell’s “Software Estimation: Demystifying the Black Art“. Steve is one of the most pragmatic technical authors I know. His whole portfolio of books is worth delving into.

Prior to describing many practical and “doable” estimation practices, Steve presents a dauntingly depressive list of estimation error sources:

- Unstable requirements

- Unfounded optimism

- Subjectivity and bias

- Unfamiliar application domain area

- Unfamiliar technology area

- Incorrect conversion from estimated time to project time (for example, assuming the project team will focus on the project eight hours per day, five days per week)

- Misunderstanding of statistical concepts (especially adding together a set of “best case” estimates or a set of “worst case” estimates)

- Budgeting processes that undermine effective estimation (especially those that require final budget approval in the wide part of the Cone of Uncertainty)

- Having an accurate size estimate, but introducing errors when converting the size estimate to an effort estimate

- Having accurate size and effort estimates, but introducing errors when converting those to a schedule estimate

- Overstated savings from new development tools or methods

- Simplification of the estimate as it’s reported up layers of management, fed into the budgeting process, and so on

- OMITTED ACTIVITIES!

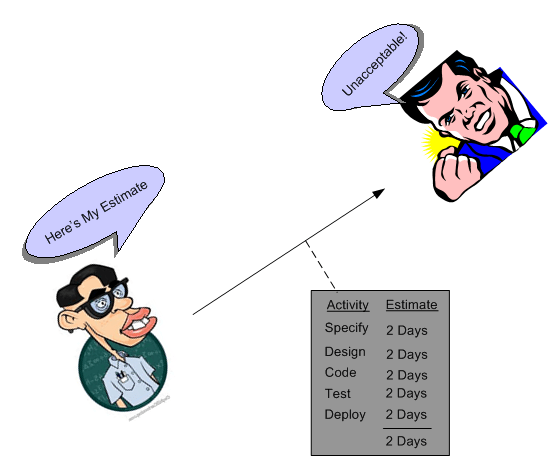

But wait! We’re not done. That last screaming bullet, OMITTED ACTIVITIES!, needs some elaboration:

- Glue code needed to use third-party or open-source software

- Ramp-up time for new team members

- Mentoring of new team members

- Management coordination/manager meetings

- Requirements clarifications

- Maintaining the scripts required to run the daily build

- Participation in technical reviews

- Integration work

- Processing change requests

- Attendance at change-control/triage meetings

- Maintenance work on previous systems during the project

- Performance tuning

- Administrative work related to defect tracking

- Learning new development tools

- Answering questions from testers

- Input to user documentation and review of user documentation

- Review of technical documentation

- Reviewing plans, estimates, architecture, detailed designs, stage plans, code, test cases

- Vacations

- Company meetings

- Holidays

- Sick days

- Weekends

- Troubleshooting hardware and software problems

It’s no freakin’ wonder that the vast majority of software-intensive projects are underestimated, no? To add insult to injury, the unspoken pressure from the “upper layers” to underestimate the activities that ARE actually included in a project plan seals the deal for “perceived” future failure, no? It’s also no wonder that after a few years, good technical people who feel that hands-on creative work is their true calling start agonizing over whether to get the hell out of such a failure-inducing system and make the move on up into the world of politics, one-upsmanship, feigned collaboration, dubious accomplishment, and strategic self-censorship. Bummer for those people and the orgs they dwell in. Bummer for “the whole“.

Killers Or Motivators?

It’s ironic that many of the words and phrases in “100 words that kill your proposal” are used by management and public relations spin doctors to project a false illusion of infallibility:

- Uniquely qualified, very unique, ensure, guarantee

- Premier, world-class, world-renowned, well-seasoned managers

- Leading company, leading edge, leading provider, industry leader, pioneers, cutting edge

- Committed, quality focused, dedicated, trustworthy, customer-first

How can these subjective and tacky words sink a business proposal on the one hand, but (supposedly) inspire and motivate on the other hand?