Archive

Espoused Vs. In-Use

Although we say we value openness, honesty, integrity, respect, and caring, we act in ways that undercut these values. For example, rather than being open and honest, we say one thing in public and another in private—and pretend that this is the rational thing to do. We then deny we are doing this and cover up our denial. – Chris Argyris

Guys like Chris Argyris, Russell Ackoff, and W. E. Deming have been virtually ignored over the years by the guild of professional management because of their in your face style. The potentates in the head shed don’t want to hear that they and their hand picked superstars are the main forces holding their borgs in the dark ages while the 2nd law of thermodynamics relentlessly chips away at the cozy environment that envelopes their (not-so) firm.

Chris Argyris’s theory of behavior in an organizational setting is based on two conflicting mental models of action:

- Model I: The objectives of this theory of action are to: (1) be in unilateral control; (2) win and do not lose; (3) suppress negative feelings; and (4) behave rationally.

- Model II: The objectives of this theory of action are to: (1) seek valid (testable) information; (2) create informed choice; and (3) monitor vigilantly to detect and correct error.

The purpose of Model I is to protect and defend the fabricated “self” against fundamental, disruptive change. The patterns of behavior invoked by model I are used by people to protect themselves against threats to their self-esteem and confidence and to protect groups, intergroups, and organizations to which they belong against fundamental, disruptive change. D’oh!

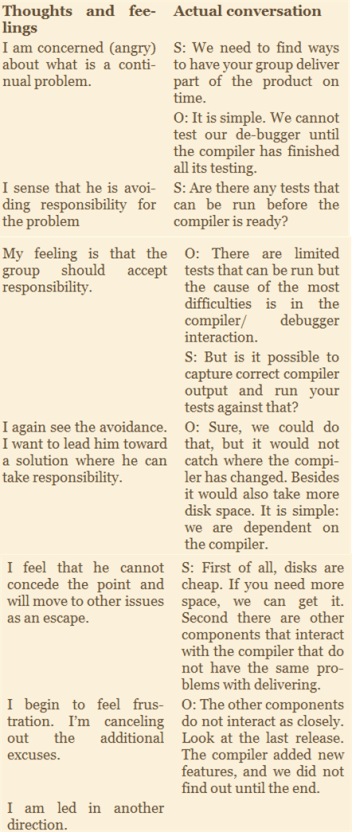

From over 10,000 empirical cases collected over decades of study, Mr. Argyris has discovered that most people (at all levels in an org) espouse Model II guidance while their daily theory in-use is driven by Model I. The tool he uses to expose this espoused vs. in-use model discrepancy is the left-hand-column/right-hand-column method, which goes something like this:

- In a sentence or two identify a problem that you believe is crucial and that you would like to solve in more productive ways than you have hitherto been able to produce.

- Assume that you are free to interact with the individuals involved in the problem in ways that you believe are necessary if progress is to be made. What would you say or do with the individuals involved in ways that you believe would begin to lead to progress. In the right hand column write what you said (or would say if the session is in the future). Write the conversation in the form of a play.

- In the left-hand column write whatever feelings and thoughts you had while you were speaking that you did not express. You do not have to explain why you did not make the feelings and thoughts public.

What follows is an example case titled “Submerging The Primary Issue” from Chris’s book, “Organizational Traps:Leadership, Culture, Organizational Design“. A superior (S) wrote it in regard to his relationship with a subordinate (O) regarding O’s performance.

The primary issue in the superior’s mind, never directly spoken in the dialog, is his perception that the subordinate lacks a sense of responsibility. The issue that *did* end up being discussed was a technical one. (I’d love to see the same case as written by the subordinate. I’d also like to see the case re-written by the superior in a non-supervised environment.)

When Mr. Argyris pointed out the discrepancy between the left and right side themes to the case writer and 1000s of other study participants, they said they didn’t speak their true thoughts out of a concern for others. They did not want to embarrass or make others defensive. Their intention was to show respect and caring.

So, are the reasons given for speaking one way while thinking a different way legitimately altruistic, or are they simply camouflage for the desire to maintain unilateral control and “win“? The evidence Chris Argyris has amassed over the years indicates the latter. But hey, those are traits that lead to the upper echelons in corpoland, no?

Nine Plus Levels

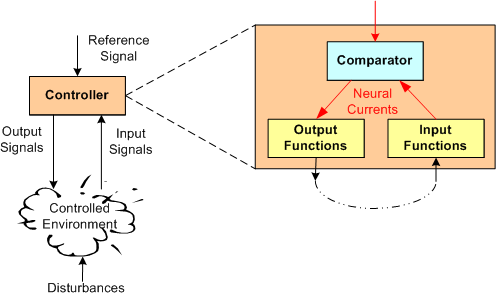

In William T. Powers’ classic and ground-breaking book “Behavior: The Control Of Perception“, Mr. Powers derives a theoretical model of the human nervous system as a stacked, nine-level hierarchical control system that collides with the standard behaviorist stimulus-response model of behavior. As the book title conveys, his ultimate heretical conclusion is that behavior controls perception; not vice-versa.

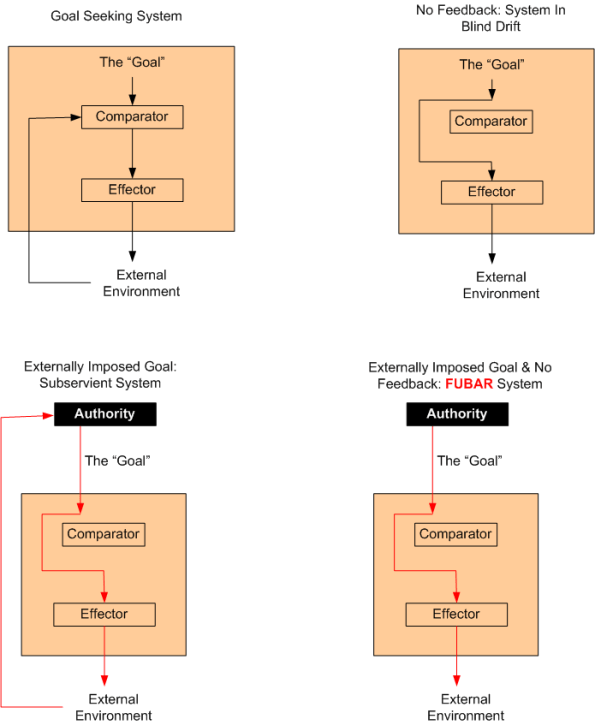

The figure below shows a model of a control system building block. The controller’s job is to minimize the error between a “reference signal” (that originates from “somewhere” outside of the controller) and some feature in the external environment that can be “disturbed” from the status quo by other, unknown forces in the environment.

Notice that the comparator is one level removed from physical reality via the transformational input and output functions. An input function converts a physical effect into a simplified neural current representation and an output function does the opposite. Afterall, everything we sense and every action we perform is ultimately due to neural currents circulating through us and being interpreted as something important to us.

So, what are the nine levels in Mr. Powers’ hierarchy, and what is the controlled quantity modeled by the reference signal at each level? BD00 is glad you asked:

Starting at the bottom level, the controlled variables get more and more abstract as we move upward in the hierarchy. Mr. Powers’ hierarchy ends at 9 levels only because he doesn’t know where to go after “concepts“.

So, who/what provides the “reference signal” at the highest level in the hierarchy? God? What quantity is it intended to control? Self-esteem? Survival? Is there a “top” at all, or does the hierarchy extend on to infinity; driven by evolutionary forces? The ultimate question is “who’s controlling the controller?“.

This post doesn’t come close to serving justice to Mr. Powers’ work. His logical, compelling, and novel derivation of the model from the ground up is fascinating to follow. Of course, I’m a layman but it’s hard to find any holes/faults in his treatise, especially in the lower, more concrete levels of the hierarchy.

Note: Thanks once again to William L. Livingston for steering me toward William T. Powers. His uncanny ability to discover and integrate the work of obscure, “ignored”, intellectual powerhouses like Mr. Powers into his own work is amazing.

Shall And Shall Not

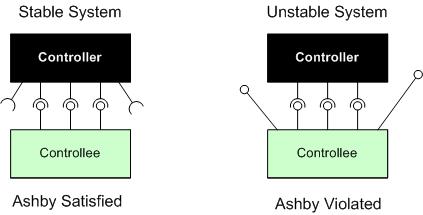

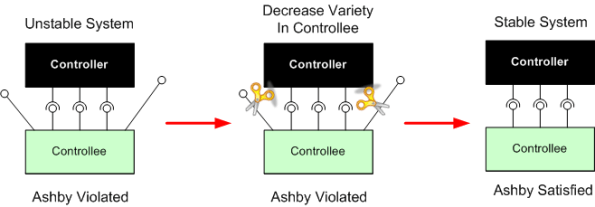

For a controlled system to remain viable and stable, Ashby’s law of requisite variety requires that the system controller(s) exhibit a wider variety of behavior than the system controllee(s). This can be accomplished by either the controller increasing its variety of responses to controllee disturbances, or by decreasing the variety of controllee disturbances relative to its own variety of control responses, or both.

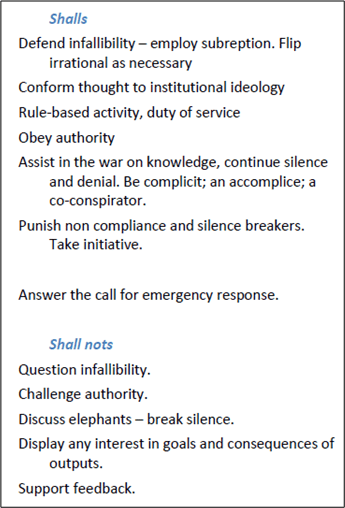

In order to comply with Ashby’s law (in conjunction with several other natural laws – 2nd law of thermo, control theory, Turing’s infallible/intelligence thesis, etc), Bill Livingston asserts that membership in any institution requires the internalization, either consciously or (more likely) unconsciously, of the following set of “shall” and “shall not” rules:

As you can see, suppressing variety in the controllee population is the preferred method of a controller aiming to satisfy Ashby’s law. The alternative, increasing its own variety of response relative to controllee variety of disturbance, requires learning and development. By definition, infallible controllers don’t need to learn and develop. They stopped learning when they achieved the status of “infallible” – either by force or by illusion.

So, what do you think? Did Mr. Livingston hit the bullseye? Miss by a mile?

Your Operational Configuration

Which system configuration do you prefer? Which system configuration is most prevalent in nature? In the “civilized” world? What’s your operating configuration, and do you have just one?

Idealized Design

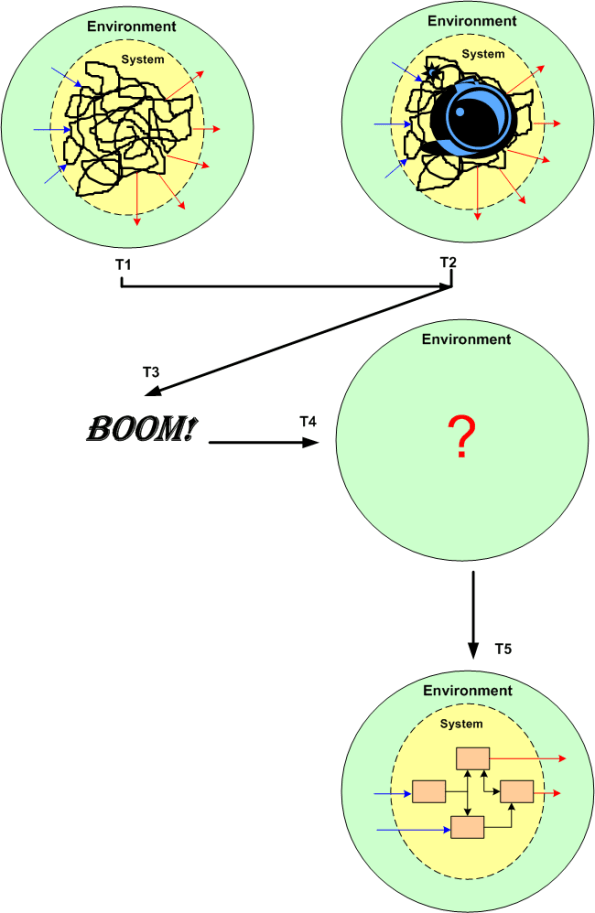

Russell Ackoff describes the process of “Idealized Design” as follows:

In this process those who formulate the vision begin by assuming that the system being redesigned was completely destroyed last night, but its environment remains exactly as it was. Then they try to design that system with which they would replace the existing system right now if they were free to replace it with any system they wanted.

The basis for this process lies in the answer to two questions. First, if one does not know what one would do if one could do whatever one wanted without constraint, how can one possibly know what to do when there are constraints? Second, if one does not know what one wants right now how can one possibly know what they will want in the future?

An idealized redesign is subject to two constraints and one design principle: technological feasibility and operational viability, and it is required to be able to learn and adapt rapidly and effectively.

So, are you ready to blow up your system? Nah, tis better to keep the unfathomable, inefficient, ineffective beast (under continuous assault from the second law of thermo) alive and unwell. It’s easier and less risky and requires no work. And hey, we can still have fun complaining about it.

Brain-Bustingly Hard

Unsettlingly, I admire the cross-disciplinary work of William L. Livingston because:

- It’s difficult to place into a nice and tidy category (systems thinking? social science? philosophy?).

- It resonates with “something” inside me but it’s brain-bustingly hard to absorb, understand, and re-communicate.

- The breadth of his vocabulary is astonishing.

- He doesn’t give a shit about becoming rich and famous.

- He digs up quotes/paragraphs from obscure, but insightful “mentors” from the past.

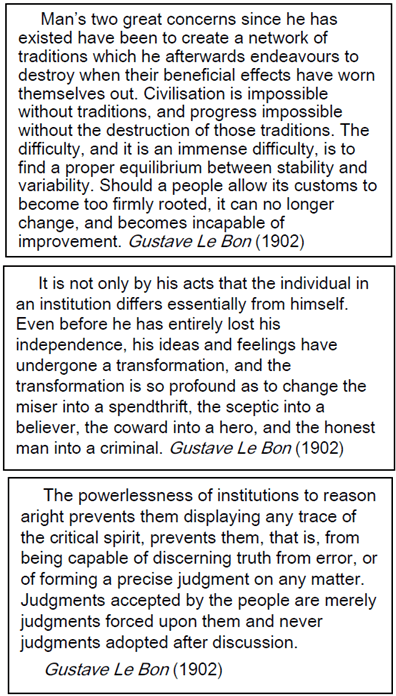

As the boxes below (plucked from the D4P4D) show, Gustave Le Bon is one of those insightful mentors, no?

A lot of Mr. Le Bon’s work is available for free online at project Gutenberg.

D4P4D Tweetfest

I’m in the process of reading William L. Livingston’s “Design For Prevention For Dummies” (D4P4D). I’m a pretty fast reader, but like my prior consumptions of all of Bill’s other dense and mind-absorbing writings, it’s a slow going affair that’s severely playin’ with my mind. I can only read about 10 fascinating pages per sitting before having to abandon ship and recoup my senses. After a martini, it’s 1 page and done. D’oh!

The book is full of masterful and tweet-worthy quotes like these:

Bill, if you’re reading this bogus blog post, I apologize for the lack of attribution in some of the tweets. I think I know you well enough that you don’t give a chit, but since I twisted your words so much in some of the tweets, I didn’t know if I should attribute them to you. Cheers!

Shifting The Burden

In a capitalist society, borgs that ship crap to their customers go out of business sooner or later:

In a corpo-socialist society, big, arrogant, and self-important borgs that ship crap to their customers get bailed out by both customers and non-customers in the form of taxpayer-financed government bailouts:

Note the feedback loop in action: crap -> customer -> money -> US Gov -> money -> to borg -> crap -> customer. It reminds me of the “shifting the burden” system archetype presented by Peter Senge in his classic book “The Fifth Discipline“. In corpo-socialist societies, the burden of staying in business is shifted from the borg itself to the American people. So much for the ideal of being responsible and accountable for your own success. It applies to individuals and small companies, but not to corpo behemoths.

Problems, Symptoms, Solutions

I haven’t done a stupid-poopy-pic in awhile… uh, since yesterday, so here’s one fer ya:

And here’s the follow on:

It’s a good thing I have 5 different poopy clips in my plagiarized BD00 graphic toolbox, no?

D4P4D

I just received two copies of William Livingston’s “Design For Prevention For Dummies” (D4P4D) gratis from the author himself. It’s actually section 7 of the “Non-Dummies” version of the book. With the addition of “For Dummies” to the title, I think it was written explicitly for me. D’oh!

The D4P is a mind bending, control theory based methodology (think feedback loops) for problem prevention in the midst of powerful, natural institutional forces that depend on problem manifestation and continued presence in order to keep the institution alive.

Mr. Livingston is an elegant, Shakespearian-type writer who’s fun to read but tough as hell to understand. I’ve enjoyed consuming his work for over 25 years but I still can’t understand or apply much of what he says – if anything!

As I slowly plod through the richly dense tome, I’ll try to write more posts that disclose the details of the D4P process. If you don’t see anything more about the D4P from me in the future, then you can assume that I’ve drowned in an ocean of confusion.