Archive

SysML Support For Requirements Modeling

“To communicate requirements, someone has to write them down.” – Scott Berkun

Prolific author Gerald Weinberg once said something like: “don’t write about what you know, write about what you want to know“. With that in mind, this post is an introduction to the requirements modeling support that’s built into the OMG’s System Modeling Language (SysML). Well, it’s sort of an intro. You see, I know a little about the requirements modeling features of SysML, but not a lot. Thus, since I “want to know” more, I’m going to write about them, damn it! 🙂

SysML Requirements Support Overview

Unlike the UML, which was designed as a complexity-conquering job performance aid for software developers, the SysML profile of UML was created to aid systems engineers during the definition and design of multi-technology systems that may or may not include software components (but which interesting systems don’t include software?). Thus, besides the well known Use Case diagram (which was snatched “as is” from the UML) employed for capturing and communicating functional requirements, the SysML defines the following features for capturing both functional and non-functional requirements:

- a stereotyped classifier for a requirement

- a requirements diagram

- six types of relationships that involve a requirement on at least one end of the association.

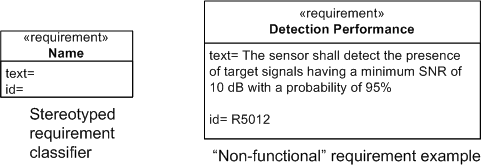

The Requirement Classifier

The figure below shows the SysML stereotyped classifier model element for a requirement. In SysML, a requirement has two properties: a unique “id” and a free form “text” field. Note that the example on the right models a “non-functional” requirement – something a use case diagram wasn’t intended to capture easily.

One purpose for capturing requirements in a graphic “box” symbol is so that inter-box relationships can be viewed in various logically “chunked“, 2-dimensional views – a capability that most linear, text-based requirements management tools are not at all good at.

Requirement Relationships

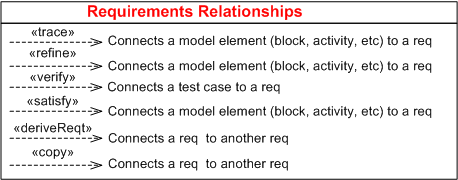

In addition to the requirement classifier, the SysML enumerates 6 different types of requirement relationships:

A SysML requirement modeling element must appear on at least one side of these relationships with the exception of <<derivReqt>> and <<copy>>, which both need a requirement on both sides of the connection.

Rather than try to write down semi-formal definitions for each relationship in isolation, I’m gonna punt and just show them in an example requirement diagram in the next section.

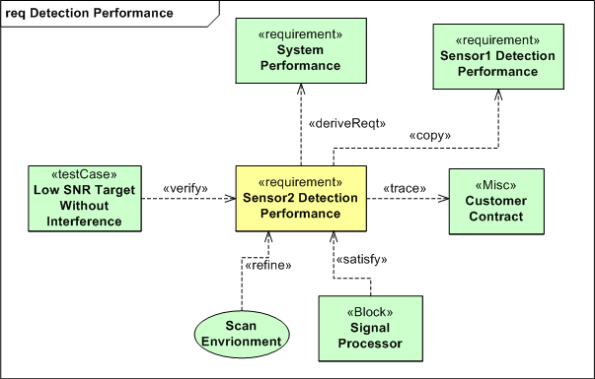

The Requirement Diagram

The figure below shows all six requirement relationships in action on one requirement diagram. Since I’ve spent too much time on this post already (a.k.a. I’m lazy) and one of the goals of SysML (and other graphical modeling languages) is to replace lots of linear words with 2D figures that convey more meaning than a rambling 1D text description, I’m not going to walk through the details. So, as Linda Richman says, “tawk amongst yawselves“.

References

1) A Practical Guide to SysML: The Systems Modeling Language – Sanford Friedenthal, Alan Moore, Rick Steiner

2) Systems Engineering with SysML/UML: Modeling, Analysis, Design – Tim Weilkiens

Increased Cost And Increased Time

Before the invention of the formal “Use Case“, and the less formal “User Story“, the classic way of integrating, structuring, and recording requirements was via the super-formal Software Requirements Specification (SRS). Like “agile” was a backlash against “waterfall“, the lightweight “Use Case” was a major diss against the heavyweight “SRS“.

However, instead of replacing SRSs with Use Cases, I surmise that many companies have shot themselves in the foot by requiring the expensive and time consuming generation and maintenance of both types of artifacts. Instead of decreasing the cost/time and increasing the quality of the requirements engineering process, they most likely have done the opposite – losing ground to smarter competitors who do one or the other effectively. D’oh! Is your company one of them?

An Answer 10 Years Later

I’ve always questioned why one of my mentors from afar, Steve Mellor, was one of the original signatories of the “Agile Manifesto” 10 years ago. He’s always been a “model-based” guy and his fellow pioneer agile dudes were obsessed with the idea that source code was the only truth – to hell with bogus models and camouflage documents. Even Grady Booch, another guy I admire, tempered the agilist obsession with code by stating something like this: “the code is the truth, but not the whole truth“.

Stephen recently sated my 10 year old curiosity in this InfoQ interview: “A Personal Reflection on Agile Ten Years On“. Here’s Steve’s answer to the question that haunted me fer 10 ears:

The other signatories were kind enough, back in 2001, to write the manifesto using the word “software” (which can include executable models), not “code” (which is more specific.) As such I felt able, in good conscience, to become a signatory to the Manifesto while continuing to promote executable modeling. Ten years on we have a standard action language for agile modeling. – Stephen J. Mellor

The reason I have great respect for Stephen (and his cohort Paul Ward) is this brilliant trilogy they wrote waaaayy back in the mid 80s:

Despite the dorky book covers and the dates they were written, I think the info in these short tomes is timeless and still relevant to real-time systems builders today. Of course, they were created before the object-oriented and multi-core revolutions occurred, but these books, using simple DeMarco/Plauger structured analysis modeling notation (before UML), nail it. By “it”, I mean the thinking, tools, techniques, idioms, and heuristics required to specify, design, and build concurrent, distributed, real-time systems that work. Buy em, read em, decide for yourself, bookmark this post, and please report your thoughts back to me.

Small, Loose, Big, Tight

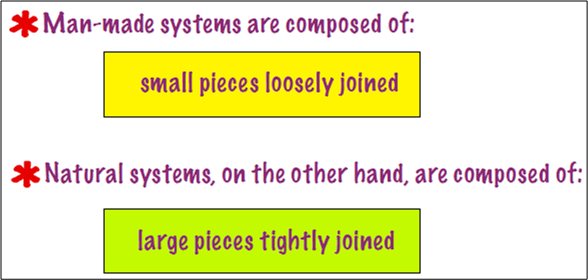

This Tom DeMarco slide from his pitch at the Software Executive Summit caused me to stop and think (Uh oh!):

I find it ironic (and true) that when man-made system are composed of “large pieces tightly joined“, they, unlike natural systems of the same ilk, are brittle and fault-intolerant. Look at the man-made financial system and what happened during the financial meltdown. Since the large institutional components were tightly coupled, the system collapsed like dominoes when a problem arose. Injecting the system with capital has ameliorated the problem, but only the future will tell if the problem was dissolved. I suspect not. Since the structure, the players, and the behavior of the monolithic system have remained intact, it’s back to business as usual.

Similarly, as experienced professionals will confirm, man made software systems composed of “large pieces tightly joined” are fragile and fault-intolerant too. These contraptions often disintegrate before being placed into operation. The time is gone, the money is gone, and the damn thing don’t work. I hate when that happens.

On the other hand, look at the glorious human body composed of “large pieces tightly joined“. It’s natural, built-in robustness and tolerance to faults is unmatched by anything man-made. You can survive and still prosper with the loss of an eye, a kidney, a leg, and a host of other (but not all) parts. IMHO, the difference is that in natural systems, the purposes of the parts and the whole are in continuous, cooperative alignment.

When the individual purposes of a system’s parts become unaligned, let alone unaligned with the purpose of the whole as often happens in man made socio-technical systems when everyone is out for themselves, it’s just a matter of time before an internal or external disturbance brings the monstrosity down to its knees. D’oh!

Quantification Of The Qualitative

Because he bucked the waterfall herd and advocated “agile” software development processes before the agile movement got started, I really like Tom Gilb. Via a recent Gilb tweet, I downloaded and read the notes from his “What’s Wrong With Requirements” keynote speech at the 2nd International Workshop on Requirements Analysis. My interpretation of his major point is that the lack of quantification of software qualities (you know, the “ilities”) is the major cause of requirements screwups, cost overruns, and schedule failures.

Here are some snippets from his notes that resonated with me (and hopefully you too):

- Far too much attention is paid to what the system must do (function) and far too little attention to how well it should do it (qualities) – in spite of the fact that quality improvements tend to be the major drivers for new projects.

- There is far too little systematic work and specification about the related levels of requirements. If you look at some methods and processes, all requirements are ‘at the same level’. We need to clearly document the level and the relationships between requirements.

- The problem is not that managers and software people cannot and do not quantify. They do. It is the lack of ‘quantification of the qualitative’ that is the problem.

- Most software professionals when they say ‘quality’ are only thinking of bugs (logical defects) and little else.

- There is a persistent bad habit in requirements methods and practices. We seem to specify the ‘requirement itself’, and we are finished with that specification. I think our requirement specification job might be less than 10% done with the ‘requirement itself’.

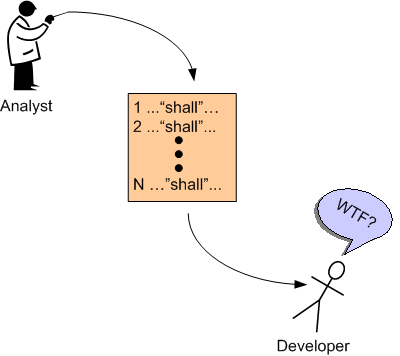

I can really relate to items 2 and 5. Expensive and revered domain specialists often do little more than linearly list requirements in the form of text “shalls”; with little supporting background information to help builders and testers clearly understand the “what” and “why” of the requirements. My cynical take on this pervasive, dysfunctional practice is that the analysts themselves often don’t understand the requirements and hence, they pursue the path of least resistance – which is to mechanically list the requirements in disconnected and incomprehensible fragments. D’oh!

Yes I do! No You Don’t!

“Jane, you ignorant slut” – Dan Ackroid

In this EETimes post, I Don’t Need No Stinkin’ Requirements, Jon Pearson argues for the commencement of coding and testing before the software requirements are well known and recorded. As a counterpoint, Jack Ganssle wrote this rebuttal: I Desperately Need Stinkin Requirements. Because software industry illuminaries (especially snake oil peddling methodologists) often assume all software applications fit the same mold, it’s important to note that Pearson and Gannsle are making their cases in the context of real-time embedded systems – not web based applications. If you think the same development processes apply in both contexts, then I urge you to question that assumption.

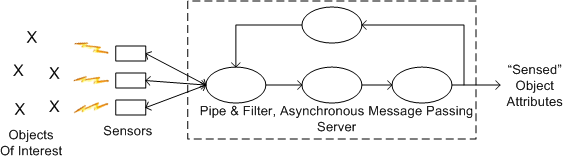

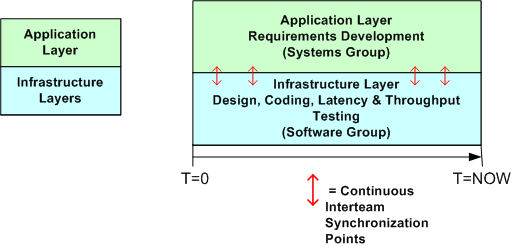

I usually agree with Ganssle on matters of software development, but Pearson also provides a thoughtful argument to start coding as soon as a vague but bounded vision of the global structure and base behavior is formed in your head. On my current project, which is the design and development of a large, distributed real-time sensor that will be embedded within a national infrastructure, a trio of us have started coding, integrating, and testing the infrastructure layer before the application layer requirements have been nailed down to a “comfortable degree of certainty”.

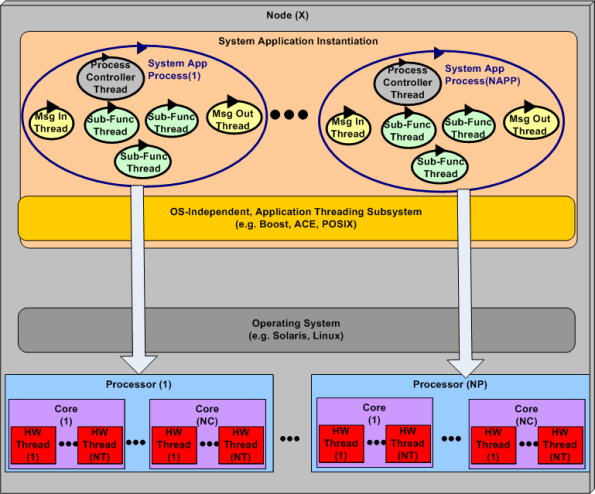

The simple figures below show how we are proceeding at the current moment. The top figure is an astronomically high level, logical view of the pipe-filter archetype that fits the application layer of our system. All processes are multi-threaded and deployable across one or more processor nodes. The bottom figure shows a simplistic 2 layer view of the software architecture and the parallel development effort involving the systems and software engineering teams. Notice that the teams are informally and frequently synchronizing with each other to stay on the same page.

The main reason we are designing and coding up the infrastructure while the application layer requirements are in flux is that we want to measure important cross-cutting concerns like end-to-end latency, processor loading, and fault tolerance performance before the application layer functionality gets burned into a specific architecture.

The main reason we are designing and coding up the infrastructure while the application layer requirements are in flux is that we want to measure important cross-cutting concerns like end-to-end latency, processor loading, and fault tolerance performance before the application layer functionality gets burned into a specific architecture.

So, do you think our approach is wasteful? Will it cause massive, downstream rework that could have been avoided if we held off and waited for the requirements to become stable?

Go, Go Go!

Rob Pike is the Google dude who created the Go programming language and he seems to be on a PR blitz to promote his new language. In this interview, “Does the world need another programming language?”, Mr. Pike says:

…the languages in common use today don’t seem to be answering the questions that people want answered. There are niches for new languages in areas that are not well-served by Java, C, C++, JavaScript, or even Python. – Rob Pike

In Making It Big in Software, UML co-creator Grady Booch seems to disagree with Rob:

It’s much easier to predict the past than it is the future. If we look over the history of software engineering, it has been one of growing levels of abstraction—and, thus, it’s reasonable to presume that the future will entail rising levels of abstraction as well. We already see this with the advent of domain-specific frameworks and patterns. As for languages, I don’t see any new, interesting languages on the horizon that will achieve the penetration that any one of many contemporary languages has. I held high hopes for aspect-oriented programming, but that domain seems to have reached a plateau. There is tremendous need to for better languages to support massive concurrency, but therein I don’t see any new, potentially dominant languages forthcoming. Rather, the action seems to be in the area of patterns (which raise the level of abstraction). – Grady Booch

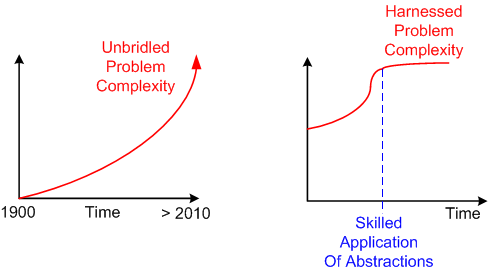

I agree with Grady because abstraction is the best tool available to the human mind for managing the explosive growth in complexity that is occurring as we speak. What do you think?

Abstraction is selective ignorance – Andrew Koenig

Processes, Threads, Cores, Processors, Nodes

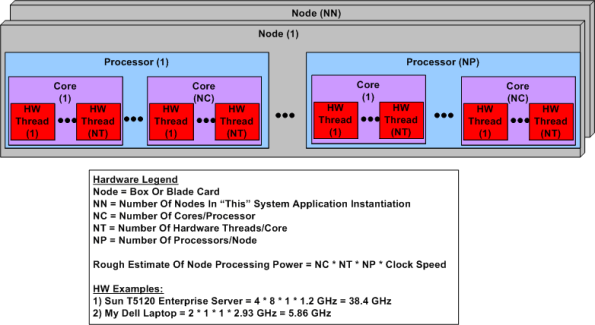

Ahhhhh, the old days. Remember when the venerable CPU was just that, a CPU? No cores, no threads, no multi-CPU servers. The figure below shows a simple model of a modern day symmetric multi-processor, multi-core, multi-thread server. I concocted this model to help myself understand the technology better and thought I would share it.

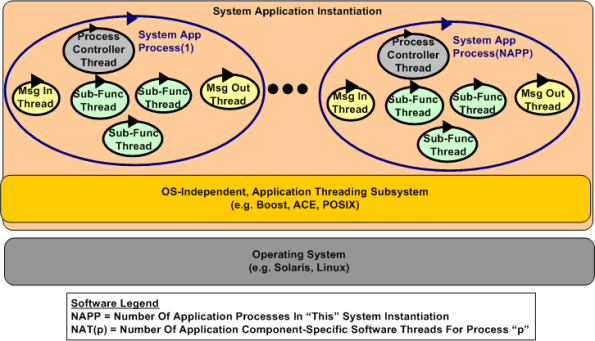

The figure below shows a generic model of a multi-process, multi-threaded, distributed, real-time software application system. Note that even though they’re not shown in the diagram, thread-to-thread and process-to-process interfaces abound. There is no total independence since the collection of running entities comprise an interconnected “system” designed for a purpose.

Interesting challenges in big, distributed system design are:

- Determining the number of hardware nodes (NN) required to handle anticipated peak input loads without dropping data because of a lack of processing power.

- The allocation of NAPP application processes to NN nodes (when NAPP > NN).

- The dynamic scheduling and dispatching of software processes and threads to hardware processors, cores, and threads within a node.

The first two bullets above are under the full control of system designers, but not the third one. The integrated hardware/software figure below highlights the third bullet above. The vertical arrows don’t do justice to the software process-thread to hardware processor-core-thread scheduling challenge. Human control over these allocation activities is limited and subservient to the will of the particular operating system selected to run the application. In most cases, setting process and thread priorities is the closest the designer can come to controlling system run-time behavior and performance.

D4P And D4F

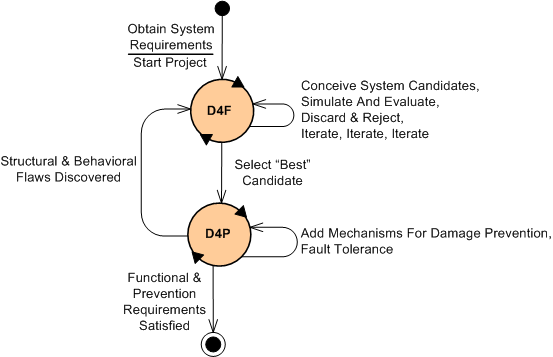

As some of you may know, my friend Bill Livingston recently finished writing his latest book, “Design For Prevention” (D4P). While doodling and wasting time (if you hadn’t noticed, I like to waste time), I concocted an idea for supplementing the D4P with something called “Design For Function” (D4F). The figure below shows, via a state machine diagram, the proposed marriage of the two complementary processes.

After some kind of initial problem definition is formulated by the owner(s) of the problem, the requirements for a “future” socio-technical system whose purpose is to dissolve the problem are recorded and “somehow” awarded to an experienced problem solver in the domain of interest. Once this occurs, the project is kicked off (Whoo Hoo!) and the wheels start churning via entry into the D4F state. In this state, various structures of connected functions are conceived and investigated for fitness of purpose. This iterative process, which includes short-cycle-run-break-fix learning loops via both computer-based and mental simulations, separates the wheat from the chaff and yields an initial “best” design according to some predefined criteria. Of course, adding to the iterative effort is the fact that the requirements will start changing before the ink dries on the initial snapshot.

Once the initial design candidate is selected for further development, the sibling D4P state is entered for the first (but definitely not last) time. In this important but often neglected problem solving system sub-state, the problem solution system candidate is analyzed for failure modes and their attendant consequences. Additional monitoring and control functional structures are then conceived and integrated into the system design to prevent failures and mitigate those failures that can’t be prevented. The goal at this point is to make the system fault tolerant and robust to large, but low probability, external and internal disturbances. Again, iterative simulations are performed as reconnaissance trips into the future to evaluate system effectiveness and robustness before it gets deployed into its environment.

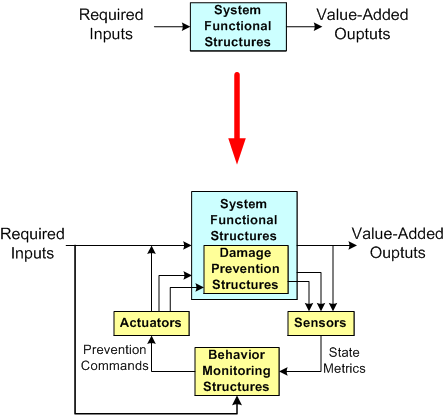

The figure below shows a dorky model of a system design before and after the D4P process has been executed. Notice the necessary added structural and behavioral complexity incorporated into the system as a result of recursively applying the D4P. Also note that the “Behavior Monitoring” structure(s), be they composed of people in a social system or computers in an automated system, or most likely both, need to have an understanding of the primary system goal seeking functions in order to effectively issue damage prevention and mitigation instructions to the various system elements. Also note that these instructions need not only be logically correct, they need to be timely for them to be effective. If the time lag between real-time problem sensing and control actuating is too great (which happens repeatedly and frequently in huge multi-layered command and control hierarchies that don’t have or want an understanding of what goes on down in the dirty boiler room), then the internal/external damage caused by the system can be as devastating as a cheaper, less complex system operating with no damage prevention capability at all.

So what do you think? Is this D4F + D4P process viable? A bunch of useless baloney?