Archive

Anomalously Huge Discrepancies

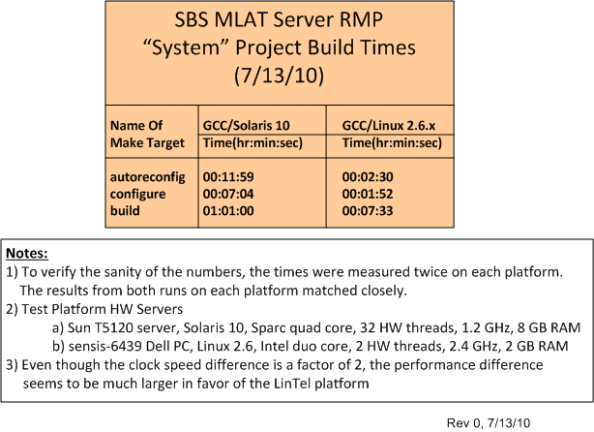

I’m currently having a blast working on the design and development of a distributed, multi-process, multi-threaded, real-time, software system with a small core group of seasoned developers. The system is being constructed and tested on both a Sparc-Solaris 10 server and an Intel-Ubuntu Linux 2.6.x server. As we add functionality and grow the system via an incremental, “chunked” development process, we’re finding anomalously huge discrepancies in system build times between the two platforms.

The table below quantifies what the team has been qualitatively experiencing over the past few months. Originally, our primary build and integration machine was the Solaris 10 server. However, we quickly switched over to the Linux server as soon as we started noticing the performance difference. Now, we only build and test on the Solaris 10 server when we absolutely have to.

The baffling aspect of the situation is that even though the CPU core clock speed difference is only a factor of 2 between the servers, the build time difference is greater than a factor of 5 in favor of the ‘nix box. In addition, we’ve noticed big CPU loading performance differences when we run and test our multi-process, multi-threaded application on the servers – despite the fact that the Sun server has 32, 1.2 GHz, hardware threads to the ‘nix server’s 2, 2.4 GHz, hardware threads. I know there are many hidden hardware and software variables involved, but is Linux that much faster than Solaris? Got any ideas/answers to help me understand WTF is going on here?

Processes, Threads, Cores, Processors, Nodes

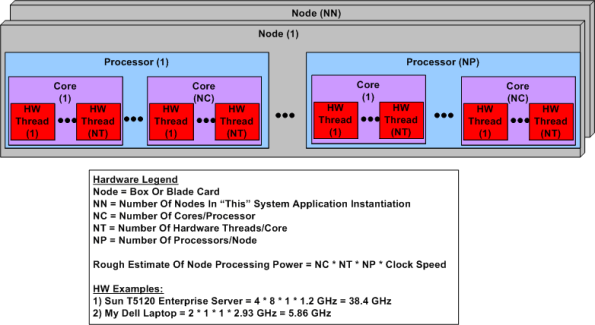

Ahhhhh, the old days. Remember when the venerable CPU was just that, a CPU? No cores, no threads, no multi-CPU servers. The figure below shows a simple model of a modern day symmetric multi-processor, multi-core, multi-thread server. I concocted this model to help myself understand the technology better and thought I would share it.

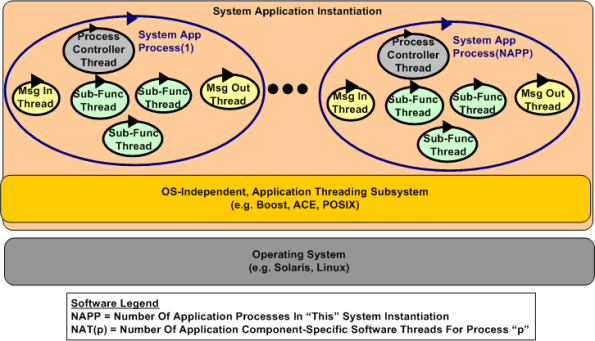

The figure below shows a generic model of a multi-process, multi-threaded, distributed, real-time software application system. Note that even though they’re not shown in the diagram, thread-to-thread and process-to-process interfaces abound. There is no total independence since the collection of running entities comprise an interconnected “system” designed for a purpose.

Interesting challenges in big, distributed system design are:

- Determining the number of hardware nodes (NN) required to handle anticipated peak input loads without dropping data because of a lack of processing power.

- The allocation of NAPP application processes to NN nodes (when NAPP > NN).

- The dynamic scheduling and dispatching of software processes and threads to hardware processors, cores, and threads within a node.

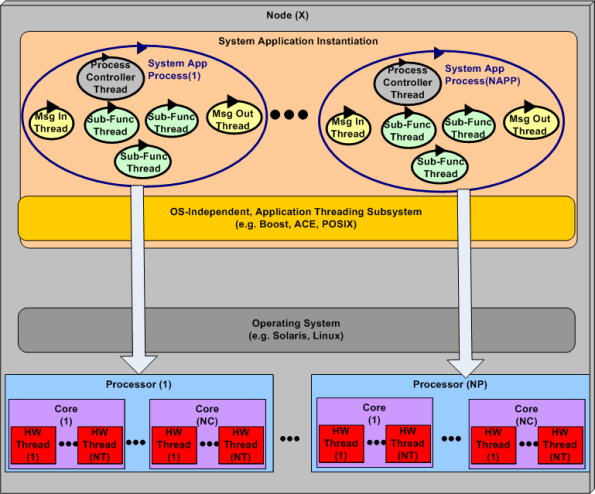

The first two bullets above are under the full control of system designers, but not the third one. The integrated hardware/software figure below highlights the third bullet above. The vertical arrows don’t do justice to the software process-thread to hardware processor-core-thread scheduling challenge. Human control over these allocation activities is limited and subservient to the will of the particular operating system selected to run the application. In most cases, setting process and thread priorities is the closest the designer can come to controlling system run-time behavior and performance.

It’s Gotta Be Free!

I love ironies because they make me laugh.

I find it ironic that some software companies will staunchly avoid paying a cent for software components that can drastically lower maintenance costs, but be willing to charge their customers as much as they can get for the application software they produce.

When it comes to development tools and (especially) infrastructure components that directly bind with their application code, everything’s gotta be free! If it’s not, they’ll do one of two things:

- They’ll “roll their own” component/layer even though they have no expertise in the component domain that cries out for the work of specialized experts. In the old days it was device drivers and operating systems. Today, it’s entire layers like distributed messaging systems and database managers.

- They’ll download and jam-fit a crappy, unpolished, sporadically active, open source equivalent into their product – even if a high quality, battle-tested commercial component is available.

Like most things in life, cost is relative, right? If a component costs $100K, the misers will cry out “holy crap, we can’t waste that money“. However, when you look at it as costing less than one programmer year, the situation looks different, no?

How about you? Does this happen, or has it happened in your company?

Architectural Choices

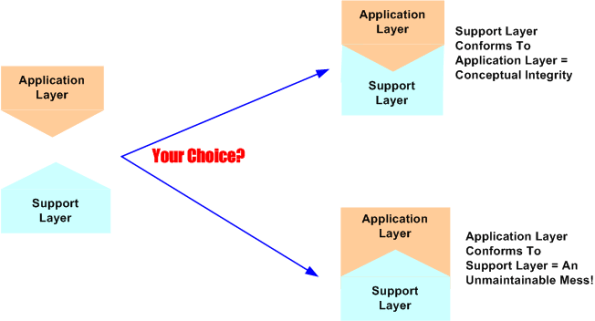

Assume that a software-intensive system you’re tasked with designing is big and complex. Because of this, you freely decide to partition the beast into two clearly delineated layers; a value-added application layer on top and an unwanted overhead, but essential, support layer on the bottom.

Now assume that a support layer for a different application layer already exists in your org – the investment has been made, it has been tested, and it “works” for those applications it’s been integrated with. As the left portion of the figure below shows, assume that the pre-existing support layer doesn’t match the structure of your yet-to-be-developed application layer. They just don’t naturally fit together. Would you:

- try to “bend” the support layer to fit your application layer (top right portion of the figure)?

- try to redesign and gronk your application layer to jam-fit with the support layer (bottom right portion of the figure)?

- ditch the support layer entirely and develop (from scratch) a more fitting one?

- purchase an externally developed support layer that was designed specifically to fit applications that fall into the same category as yours?

After contemplating long term maintenance costs, my choice is number 4. Let support layer experts who know what they’re doing shoulder the maintenance burden associated with the arcane details of the support layer. Numbers 1 through 3 are technically riskier and financially costlier because, unless your head is screwed on backwards, you should be tasking your programmers with designing and developing application layer functionality that is (supposedly) your bread winner – not mundane and low value-added infrastructure functionality.

Skill Acquisition

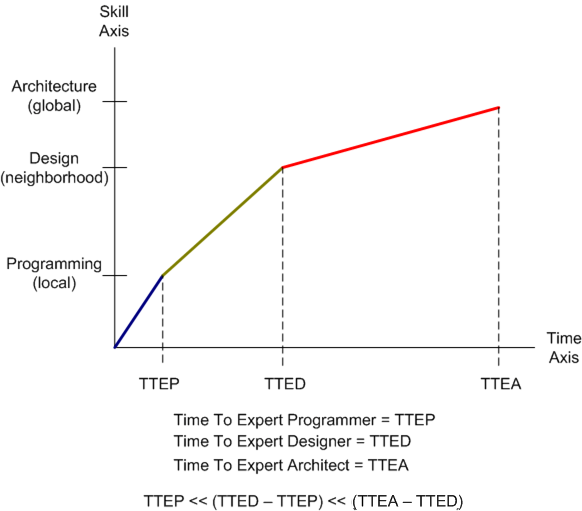

Check out the graph below. It is a totally made up (cuz I like to make things up) fabrication of the relationship between software skill acquisition and time (tic-toc, tic-toc). The y-axis “models” a simplistic three skill breakdown of technical software skills: programming (in-the-very-small) , design (in-the-small) and architecture (in-the-large). The x-axis depicts time and the slopes of the line segments are intended to convey the qualitative level of difficulty in transitioning from one area of expertise into the next higher one in the perceived value-added chain. Notice that the slopes decrease with each transition; which indicates that it’s tougher to achieve the next level of expertise than it was to achieve the previous level of expertise.

The reason I assert that moving from level N to level N+1 takes longer than moving from N-1 to N is because of the difficulty human beings have dealing with abstraction. The more concrete an idea, action or thought is, the easier it is to learn and apply. It’s as simple as that.

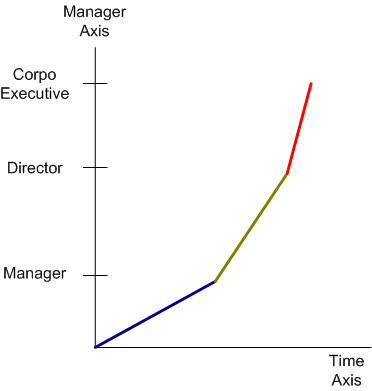

The figure below shows another made up management skill acquisition graph. Note that unlike the technical skill acquisition graph, the slopes decrease with each transition. This trend indicates that it’s easier to achieve the next level of expertise than it was to achieve the previous level of expertise. Note that even though the N+1 level skills are allegedly easier to acquire over time than the Nth level skill set, securing the next level title is not. That’s because fewer openings become available as the management ladder is ascended through whatever means available; true merit or impeccable image.

Error Acknowledgement: I forgot to add a notch with the label DIC at the lower left corner of the graph where T=0.

Hold The Details, Please

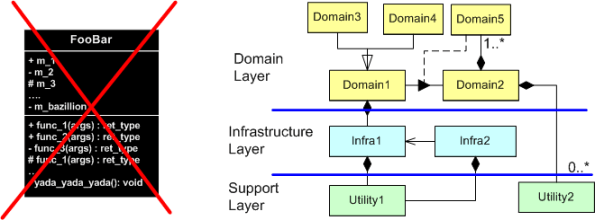

When documenting software designs (in UML, of course) before, during, or after writing code, I don’t like to put too much detail in my models. By details, I mean exposing all public/protected/private data members and functions and all intra-member processing sequences within each class. I don’t like doing it for these reasons:

- I don’t want to get stuck in a time-busting, endless analysis paralysis loop.

- I don’t want a reviewer or reader to lose the essence of the design in a sea of unnecessary details that obscure the meaning and usefulness of the model.

- I don’t want every little code change to require a model change – manual or automated.

I direct my attention to the higher levels of abstraction, focusing on the layered structure of the whole. By “layered structure”, I mean the creation and identification of all the domain level classes and the next lower level, cross-cutting infrastructure and utility classes. More importantly, I zero in on all the relationships between the domain and infrastructure classes because the real power of a system, any system, emerges from the dynamic interactions between its constituent parts. Agonizing over the details within each class and neglecting the inter-class relationships for a non-trivial software system can lead to huge, incoherent, woeful classes and an unmaintainable downstream mess. D’oh!

How about you? What personal guidelines do you try to stick to when modeling your software designs? What, you don’t “do documentation“? If you’re looking to move up the value chain and become more worthy to your employer and (more importantly) to yourself, I recommend that you continuously learn how to become a better, “light” documenter of your creations. But hey, don’t believe a word I say because I don’t have any authority-approved credentials/titles and I like to make things up.

Layered Obsolescence

For big and long-lived software-intensive systems, the most powerful weapon in the fight against the relentless onslaught of hardware and software obsolescence is “layering”. The purer the layering, the better.

In a pure layered system, source code in a given layer is only cognizant of, and interfaces with, code in the next layer down in the stack. Inversion of control frameworks where callbacks are installed in the next layer down are a slight derivative of pure layering. Each given layer of code is purposefully designed and coded to provide a single coherent service for the next higher, and more abstract, layer. However, since nothing comes for free, the tradeoff for architecting a carefully layered system over a monolith is performance. Each layer in the cake steals processor cycles and adds latency to the ultimate value-added functionality at the top of the stack. When layering rules must be violated to meet performance requirements, each transgression must be well documented for the poor souls who come on-board for maintenance after the original development team hits the high road to promotion and fame.

Relative to a ragged and loosely controlled layering scheme (or heaven forbid – no discernable layering), the maintenance cost and technical risk of replacing any given layer in a purely layered system is greatly reduced. In a really haphazard system architecture, trying to replace obsolete, massively tentacled components with fuzzy layer boundaries can bring the entire house of cards down and cause great financial damage to the owning organization.

“The entire system also must have conceptual integrity, and that requires a system architect to design it all, from the top down.” – Fred Brooks

Having said all this motherhood and apple pie crap that every experienced software developer knows is true, why do we still read and hear about so many software maintenance messes? It’s because someone needs to take continuous ownership of the overall code base throughout the lifecycle and enforce the layering rules. Talking and agreeing 100% about “how it should be done” is not enough.

Since:

- it’s an unpopular job to scold fellow developers (especially those who want to put their own personal coat of arms on the code base),

- it’s under-appreciated by all non-software management,

- there’s nothing to be gained but extra heartache for any bozo who willfully signs up to the enforcement task,

very few step up to the plate to do the right thing. Can you blame them? Those that have done it and have been rewarded by excommunication from the local development community in addition to indifference from management, rarely do it again – unless coerced.

The Loop Of Woe

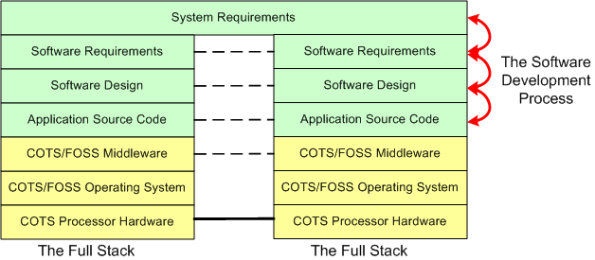

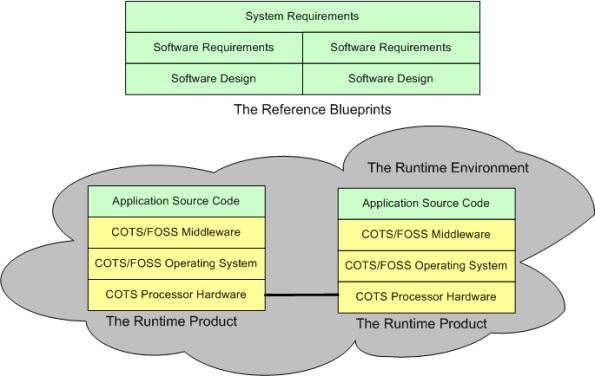

When a “side view” of a distributed software architecture is communicated, it’s sometimes presented with a specific instantiation of something like this four layer drawing; where COTS = Commercial Off The Shelf and FOSS=Free Open Source Software:

I think that neglecting the artifacts that capture the thinking and rationale in the more abstract higher layers of the stack is a recipe for high downstream maintenance costs, competitive disadvantage, and all around stakeholder damage. For “big” systems, trying to find/fix bugs, or determining where new feature source code must be inserted among 100s of thousands of lines of code, is a huge cost sink when a coherent full stack of artifacts is not available to steer the hunt. The artifacts don’t have to be high ceremony, heavyweight boat anchors, they just have to be useful. Simple, but not simplistic.

For safety-critical systems, besides being a boon to maintenance, another increasingly important reason for treating the upper layers with respect is certification. All certification agencies require an auditable and scrutably connected path from requirements down through the source code. The classic end run around the certification obstacle when the content of the upper layers is non-existent or resembles swiss cheese is to get the system classified as “advisory”.

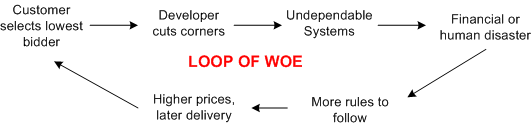

Frenetic , clock-watching managers and illiterate software developers are the obvious culprits of upper layer neglect but, ironically, the biggest contributors to undependable and uncertifiable systems are customers themselves. By consistently selecting the lowest bidder during acquisition, customers unconsciously encourage corner-cutting and apathy towards safety.

Frenetic , clock-watching managers and illiterate software developers are the obvious culprits of upper layer neglect but, ironically, the biggest contributors to undependable and uncertifiable systems are customers themselves. By consistently selecting the lowest bidder during acquisition, customers unconsciously encourage corner-cutting and apathy towards safety.

Got any ideas for breaking the loop of woe? I wish I did, but I don’t.

Background Daemons

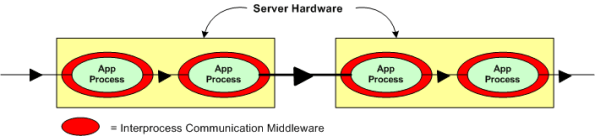

Assume that you have to build a distributed real-time system where your continuously communicating application components must run 24×7 on multiple processor nodes netted together over a local area network. In order to save development time and shield your programmers from the arcane coding details of setting up and monitoring many inter-component communication channels, you decide to investigate pre-written communication packages for inclusion into your product. After all, why would you want your programmers wasting company dollars developing non-application layer software that experts with decades of battle-hardened experience have already created?

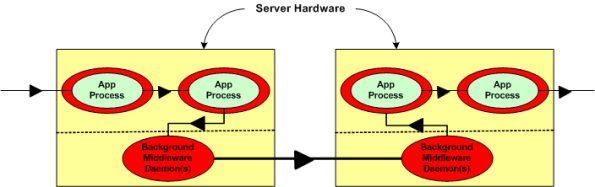

Now, assume that the figure below represents a two node portion of your many-node product where a distributed architecture middleware package has been linked (statically or dynamically) into each of your application components. By distributed architecture, I mean that the middleware doesn’t require any single point-of-failure daemons running in the background on each node.

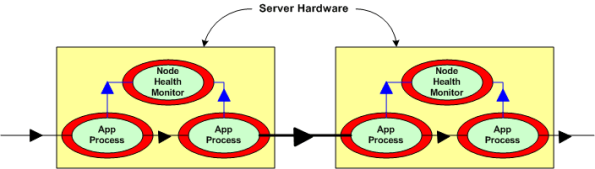

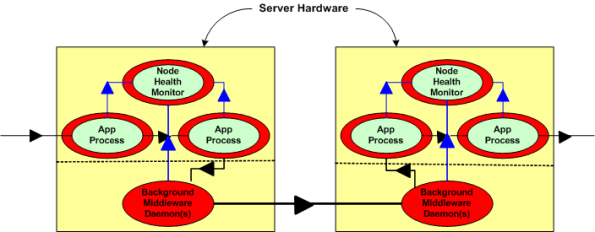

Next, assume that to increase reliability, your system design requires an application layer health monitor component running on each node as in the figure below. Since there are no daemons in the middleware architecture that can crash a node even when all the application components on that node are running flawlessly, the overall system architecture is more reliable than a daemon-based one; dontcha think? In both distributed and daemon-based architectures, a single application process crash may or may not bring down the system; the effect of failure is application-specific and not related to the middleware architecture.

The two figures below represent a daemon-based alternative to the truly distributed design previously discussed. Note the added latency in the communication path between nodes introduced by the required insertion of two daemons between the application layer communication endpoints. Also note in the second figure that each “Node Health Monitor” now has to include “daemon aware” functionality that monitors daemon state in addition to the co-resident application components. All other things being equal (which they rarely are), which architecture would you choose for a system with high availability and low latency requirements? Can you see any benefits of choosing the daemon-based middleware package over a truly distributed alternative?

The most reliable part in a system is the one that is not there – because it isn’t needed.

Data-Centric, Transaction-Centric

The market (ka-ching!, ka-ching!) for transaction-centric enterprise IT (Information Technology) systems dwarfs that for real-time, data-centric sensor control systems. Because of this market disparity, the lion’s share of investment dollars is naturally and rightfully allocated to creating new software technologies that facilitate the efficient development of behemoth enterprise IT systems.

I work in an industry that develops and sells distributed, real-time, data-centric sensor systems and it frustrates me to no end when people don’t “see” (or are ignorant of) the difference between the domains. With innocence, and unfortunately, ignorance embedded in their psyche, these people try to jam-fit risky, transaction-centric technologies into data-centric sensor system designs. By risky, I mean an elevated chance of failing to meet scalability, real-time throughput and latency requirements that are much more stringent for data-centric systems than they are for most transaction-centric systems. Attributes like scalability, latency, capacity, and throughput are usually only measurable after a large investment has been made in the system development. To add salt to the wound, re-architecting a system after the mistake is discovered and ( more importantly) acknowledged, delays release and consumes resources by amounts that can seriously damage a company’s long term viability.

As an example, consider the CORBA and DDS OMG standard middleware technologies. CORBA was initially designed (by committee) from scratch to accommodate the development of big, distributed, client-server, transaction-centric systems. Thus, minimizing latency and maximizing throughout were not the major design drivers in its definition and development. DDS was designed to accommodate the development of big, distributed, publisher-subscriber, data-centric systems. It was not designed by a committee of competing vendors each eager to throw their pet features into a fragmented, overly complex quagmire. DDS was derived from the merger of two fielded and proven implementations, one by Thales (distributed naval shipboard sensor control systems) and the other by RTI (distributed robotic sensor and control systems). In contrast, as a well meaning attempt to be all things to all people, publish-subscribe capability was tacked on to the CORBA beast after the fact. Meanwhile, DDS has remained lean and mean. Because of the architecture busting risk for the types of applications DDS targets, no client-server capability has been back-fitted into its design.

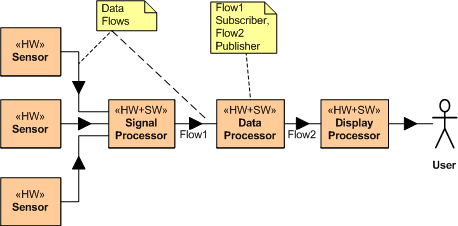

Consider the example distributed, data-centric, sensor system application layer design below. If this application sits on top of a DDS middleware layer, there is no “intrusion” of a (single point of failure) CORBA broker into the application layer. Each application layer system component simply boots up, subscribes to the topic (message) streams it needs, starts crunching them with it’s app-specific algorithms, and publishes its own topic instances (messages) to the other system components that have subscribed to the topic.

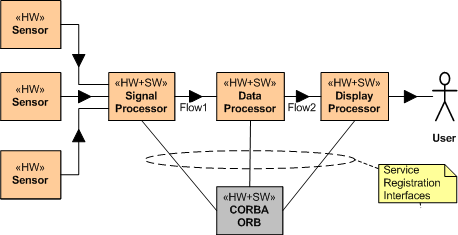

Now consider a CORBA broker-based instantiation of this application example (refer to the figure below). Because of the CORBA requirement for each system component to register with an all knowing centralized ORB (Object Request Broker) authority, CORBA “leaks” into the application layer design. After registration, and after each service has found (via post-registration ORB lookup) the other services it needs to subscribe to, the ORB can disappear from the application layer – until a crash occurs and the system gets hosed. DDS avoids leakage into the value-added application layer by avoiding the centralized broker concept and providing for fully distributed, under-the-covers, “auto-discovery” of publishers and subscribers. No DDS application process has to interact with a registrar at startup to find other components – it only has to tell DDS which topics it will publish and which topics it needs to subscribe to. Each CORBA component has to know about the topics it needs and the services it needs to subscribe to.

The more a system is required to accommodate future growth, the more inapplicable a centralized ORB-based architecture is. Relative to a fully distributed coordination and auto-discovery mechanism that’s transparent to each application component, attempting to jam fit a single, centralized coordinator into a large scale distributed system so that the components can find and interact with each other reduces robustness, fault tolerance, and increases long term maintenance costs.