Archive

Code First And Discover Later

In my travels through the whacky world of software development, I’ve found that bottom up design (a.k.a code first and “discover” the real design later) can lead to lots of unessential complexity getting baked into the code. Once this unessential complexity, in the form of extraneous classes and a rats nest of unneeded dependencies, gets baked into the system and the contraption “appears to work” in a narrow range of scenarios, the baker(s) will tend to irrationally defend the “emergent” design to the death. After all, the alternative would be to suffer humility and perform lots of risky, embarrassing, and ego-busting disentanglement rework. Of course, all of these behaviors and processes are socially unacceptable inside of orgs with macho cultures; where publicly admitting you’re wrong is a career-ending move. And that, my dear, is how we have created all those lovable, “legacy” systems that run the world today.

Don’t get BD00 wrong here. The esteemed one thinks that bottom up design and coding is fine for small scoped systems with around 7 +/- 2 classes (Miller’s number), but this “easy and fun and fast” approach sure doesn’t scale well. Even more ominously, the bottom up coding and emergent design strategy is unacceptable for long-lived, safety-critical systems that will be scrutinized “later on” by external technical inspectors.

Not Either, But Both?

I recently dug up an old DDS tutorial pitch by distributed system middleware expert extraordinaire, Doug Schmidt. The last slide in the pitch shows a side-by-side, high-level feature comparison of CORBA and DDS:

High performance middleware technologies like CORBA and DDS are big, necessarily complex beasts that have high learning curves. Thus, I’m not so sure I agree with Doug’s assessment that complex software systems (like sensor-based command and control systems) need both. One can build a pub-sub mechanism on top of CORBA (using the notification, event, or messaging services) and one can build a client-server, request-response mechanism on top of DDS (using the TCP/IP-like “reliability” QoS). What do you think about the tradeoff? Fill the holes yourself with a tad of home-grown infrastructure code, or use both and create a two-headed, fire-breathing dragon?

Too Detailed, Too Fast

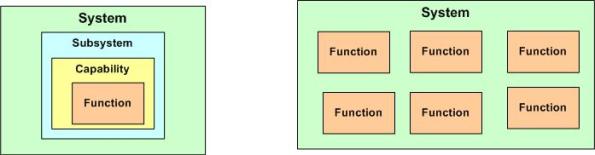

One of the dangers system designers continually face is diving into too much detail, too fast. Given a system problem statement, the tendency is to jump right into fine-grained function (feature) definitions so that the implementation can get staffed and started pronto. Chop-chop, aren’t you done yet?

The danger in bypassing a multi-leveled analysis/synthesis effort and directly mapping the problem elements into concrete, buildable functions is that important, unseen, higher level relationships can be missed – and you may pay the price for your haste with massive downstream rework and integration problems. Of course, if the system you’re building is simple enough or you’re adding on to an existing system, then the skip level approach may work out just fine.

Bounded Solution Spaces

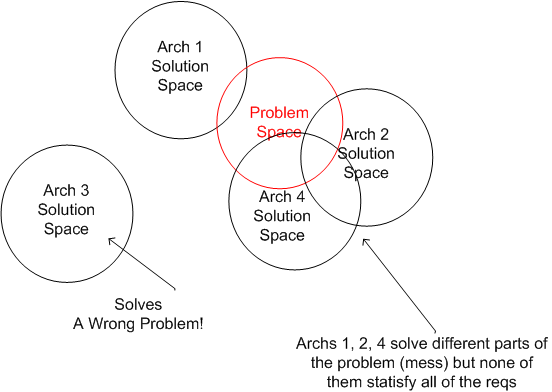

As a result of an interesting e-conversation with my friend Charlie Alfred, I concocted this bogus graphic:

Given a set of requirements, the problem space is a bounded (perhaps wrongly, incompletely, or ambiguously) starting point for a solution search. I think an architect’s job is to conjure up one or more solutions that ideally engulf the entire problem space. However, the world being as messy as it is, different candidates will solve different parts of the problem – each with its own benefits and detriments. Either way, each solution candidate bounds a solution space, no?

A Risky Affair

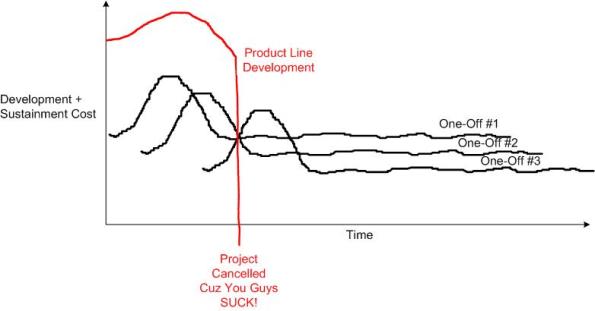

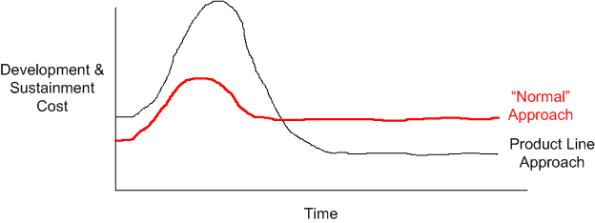

The figure below shows the long term savings potential of a successful Software Product Line (SPL) over a one-off system development strategy. Since 2/3 to 3/4 of the total lifecycle cost of a long-lived software system is incurred during sustainment (and no, I don’t have any references handy), with an SPL infrastructure in place, patience and discipline (if you have them) literally pay off. Even though short term costs and initial delivery times suffer, cost and time savings start to accrue “sometime” downstream. Of course, if your business only produces small, short-lived products, then implementing an SPL approach is not a very smart strategy.

If you think developing a one-off, software-intensive product is a risky affair, then developing an SPL can seem outright suicidal. If your past history indicates that you suck at one-off development (you do track and reflect upon past schedule/cost/quality metrics as your CMMI-compliant process sez you do, right?), then rejecting all SPL proposals is the only sane thing to do…. because this may happen:

The time is gone, the money is gone, and you’ve got nothing to show for it. D’oh! I hate when that happens.

Related Articles

The Odds May Not Be Ever In Your Favor (Bulldozer.com)

Out Of One, Many (Bulldozer.com)

Rules Of Thumb

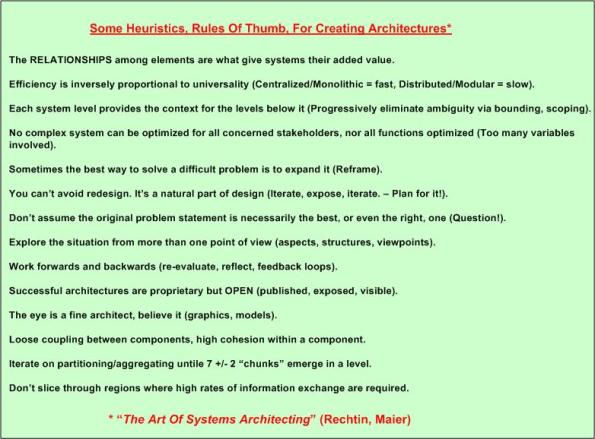

Look what I dug up in my archives:

Hopefully, this list may provide some aid to at least one poor, struggling soul out in the ether.

Bring Back The Old

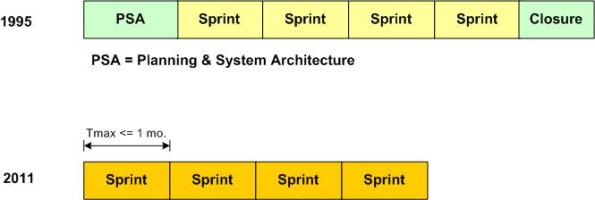

The figure below shows the phases of Scrum as defined in 1995 (“Scrum Development Process“) and 2011 (The 2011 Scrum Guide). By truncating the waterfall-like endpoints, especially the PSA segment, the development framework became less prescriptive with regard to the front and back ends of a new product development effort. Taken literally, there are no front or back ends in Scrum.

The well known Scrum Sprint-Sprint-Sprint-Sprint… work sequence is terrific for maintenance projects where the software architecture and development/build/test infrastructure is already established and “in-place“. However, for brand new developments where costly-to-change upfront architecture and infrastructure decisions must be made before starting to Sprint toward “done” product increments, Scrum no longer provides guidance. Scrum is mum!

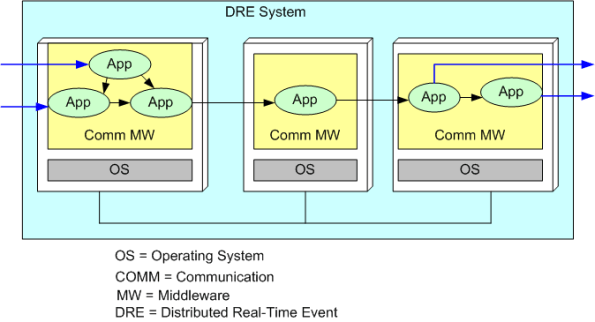

The figure below shows a generic DRE system where raw “samples” continuously stream in from the left and value-added info streams out from the right. In order to minimize the downstream disaster of “we built the system but we discovered that the freakin’ architecture fails the latency and/or thruput tests!“, a bunch of critical “non-functional” decisions and must be made and prototyped/tested before developing and integrating App tier components into a potentially releasable product increment.

I think that the PSA segment in the original definition of Scrum may have been intended to mitigate the downstream “we’re vucked” surprise. Maybe it’s just me, but I think it’s too bad that it was jettisoned from the framework.

The time’s gone, the money’s gone, and the damn thing don’t work!

The Odds May Not Be Ever In Your Favor

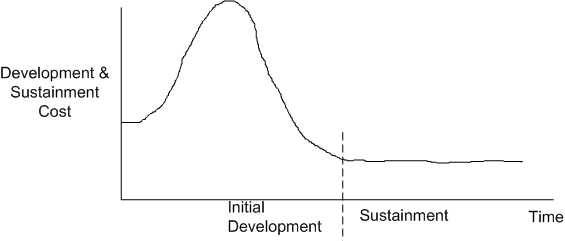

The sketch below models a BD00 concocted reference cost curve for a single, one-off, software-intensive product. Note that since the vast majority of the accumulated cost (up to 3/4 of it according to some experts) of a long-lived product is incurred during the sustainment epoch of a product’s lifetime, the graph is not drawn to scale.

If you’re in the business of providing quasi-similar, long-lived, software-intensive products in a niche domain, one strategy for keeping sustainment costs low is to institutionalize a Software Product Line Approach (SPLA) to product development.

A software Product Line is a set of software-intensive systems that share a common, managed set of features satisfying the specific needs of a particular market segment or mission and that are developed from a common set of core assets in a prescribed way. – Software Engineering Institute

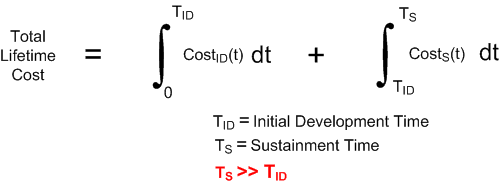

As the diagram below shows, the idea behind the SPLA is to minimize the Total Lifetime Cost by incurring higher short-term costs in order to incur lower long-term costs. Once the Product Line infrastructure is developed and placed into operation, instantiating individual members of the family is much less costly and time consuming than developing a one-off implementation for each new application and/or customer.

Some companies think themselves into a false sense of efficiency by fancying that they’re employing an SPLA when they’re actually repeatedly reinventing the wheel via one-off, copy-and-paste engineering.

You can’t copy and paste your way to success – Unknown

If your engineers aren’t trained in SPLA engineering and you’re not using the the terminology of SPLA (domain scoping, core assets, common functionality, variability points, etc) in your daily conversations, then the odds may not be ever in your favor for reaping the benefits of an SPLA.

Related articles

- Out Of One, Many (bulldozer00.com)

- Product Line Blueprint (bulldozer00.com)

What’s Next?

I was browsing through some old powerpoint pitches and I cam across this potentially share-worthy graphic:

I’m sorry for the poor resolution. I was too lazy to spruce it up.

Message-Centric Vs. Data-Centric

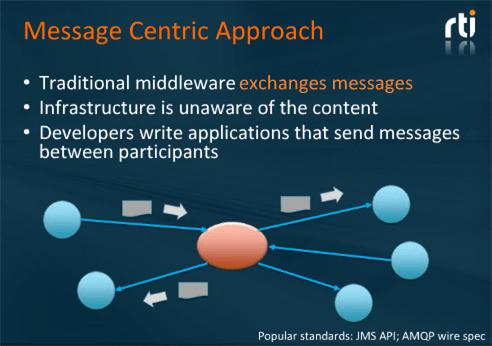

The slide below, plagiarized from a recent webinar presented by RTI Inc’s CEO Stan Schneider, shows the evolution of distributed system middleware over the years.

At first, I couldn’t understand the difference between the message-centric pub-sub (MCPS) and data-centric pub-sub (DCPS) patterns. I thought the difference between them was trivial, superficial, and unimportant. However, as Stan’s webinar unfolded, I sloowly started to “get it“.

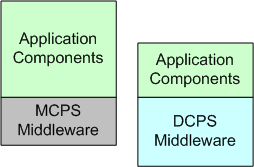

In MCPS, application tier messages are opaque to to the middleware (MW). The separation of concerns between the app and MW tiers is clean and simple:

In DCPS systems, app tier messages are transparent to the MW tier – which blurs the line between the two layers and violates the “ideal” separation of concerns tenet of layered software system design. Because of this difference, the term “message” is superceded in DCPS-based technologies (like the OMG‘s DDS) by the term “topic“. The entity formerly known as a “message” is now defined as a topic sample.

Unlike MCPS MW, DCPS MW supports being “told” by the app tier pub-sub components which Quality Of Service (QoS) parameters are important to each of them. For example, a publisher can “promise” to send topic samples at a minimum rate and/or whether it will use a best-effort UDP-like or reliable TCP-like protocol for transport. On the receive side, a subscriber can tell the MW that it only wants to see every third topic sample and/or only those samples in which certain data-field-filtering criteria are met. DCPS MW technologies like DDS support a rich set of QoS parameters that are usually hard-coded and frozen into MCPS MW – if they’re supported at all.

With smart, QoS-aware DCPS MW, app components tend to be leaner and take less time to develop because the tedious logic that implements the QoS functionality is pushed down into the MW. The app simply specifies these behaviors to the MW during launch and it gets notified by the MW during operation when QoS requirements aren’t being, or can’t be, met.

The cost of switching from an MCPS to a DCPS-based distributed system design approach is the increased upfront, one-time, learning curve (or more likely, the “unlearning” curve).