Archive

Value And Effectiveness

A few weeks ago, my friend Charlie Alfred challenged me to take a break from railing against the dysfunctional behaviors that “emerge” from the vertical command and control nature of hierarchies. He suggested that I go “horizontal“. Well, I haven’t answered his challenge, but Charlie came through with this wonderful guest post on that very subject. I hope you enjoy reading Charlie’s insights on the horizontal communication gaps that appear between specialized silos as a result of corpo growth. Please stop by his blog when you get a chance.

——————————————————————————————————————————–

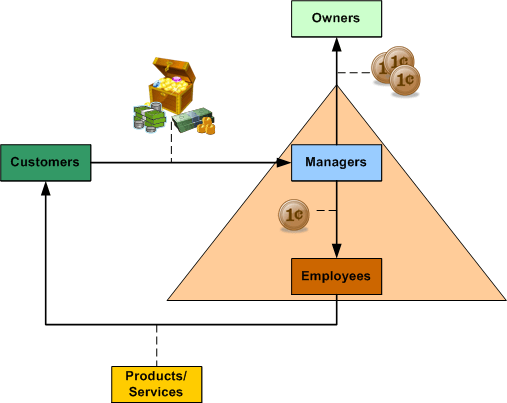

In “Profound Shift in Focus“, BD00 discusses the evolution of value-focused startups into cost-focused borgs. There’s ample evidence for this, but one wonders what lies at the root?

One clue is Russell Ackoff’s writings on analysis and synthesis. Analysis starts with a system and takes it apart, in the pursuit of understanding how it works. Synthesis, starts with a system, identifies the systems which contain it, and studies the role of the original system within its containing systems in the pursuit of understanding why it must work that way.

Analytical thinking is the engine that powered the Industrial Revolution and many of the most important scientific advances of the 21st century. Understanding how things work is essential to making them work better (also known as efficiency). Today, we have better automobiles, airplanes, computers, phones, and TV’s than our parents. And we owe much of this to analytical thinking.

But one of the side effects of analytical thinking is specialization. As understanding deepens, the volume of subject matter knowledge explodes. This leads to the old joke.

Q: What’s the difference between an engineer and an executive?

A: Every day engineers learn more and more about less and less, until one day they know everything about nothing, while executives learns less and less about more and more, until one day they know nothing about everything.

But all joking aside, this is a serious concern. The vast majority of organizations today are organized functionally: sales, marketing, finance, engineering, manufacturing, HR, IT, etc. And withing these organizations, there are even more specializations. Marketing has specialists in advertising, public relations, research, distribution channels, and product management. Engineering has chemical, mechanical, electrical, firmware, and software engineers. Even in software development, you have specialists in user interfaces, networking, databases. realtime embedded and project management.

One of the critical problems is that most people working in each of these areas become overspecialized. They spend so much time accumulating and applying specialized knowledge, that they can only communicate with people in their own specialty. If you don’t believe me, observe a two hour meeting involving somebody from sales, market research, product management, mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, finance, and purchasing.

In Mythical Man Month, Frederick Brooks retells the Tower of Babel as a project management story. It fits perfectly, because the root cause of the Tower of Babel failure was overspecialization and a failure to communicate. Today, instead of talking Hebrew, Arabic, Persian and Greek, we talk gross margin, differentiation, segmentation, tensile strength, electromagnetic interference, and virtual inheritance.

And our communication has another quality. Solution focus. We routinely argue the flaws and merits of solutions with only the foggiest understanding of what the problem is. And we use the vast levels of specialized knowledge from our respective disciplines to shout down the cretans who disagree with us.

Cost reduction and efficiency live in the same neighborhood as specialization and analytical thinking:

- If we replace these two steps with this one, the process will be faster.

- If we replace this part with this other part, the unit cost will be reduced by 2%.

- If we consolidate these three models into one, we can reduce inventory by 20%.

If efficiency is “doing things the right way”, then effectiveness is “doing the right things the right way.” Value lives next door to effectiveness and both live in the same neighborhood as synthesis. Value, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. Products and services can deliver benefits, but only the buyers and users can apply these benefits to realize value. Consider smartphones. Some people only use their phones for mobile calls, others for text messaging, some to read books on the train.

So in the end, there are a couple of reasons that startups are inherently focused on value. First, because they are small, specialization is a liability. Most people in startups do several jobs (well), by necessity. Second, because they are not yet profitable and self-sustaining, their survival is highly dependent on their surroundings (e.g. customers, competitors, economic conditions). This requires more synthesis than analysis.

As they grow, their strategy shifts to cost. Michael Porter writes about this in Competitive Advantage. And guess what, every one of us bargain-hunting, coupon-clipping, “buy one get one free” consumers is the root cause of this. Why mention this? Because synthetic thinkers love systems with feedback loops!

Unstated, But Deeply Rooted

Maturity is a state that most companies eventually reach. To break out of – or avoid – maturity, innovation is required: new products or services, new marketing or markets, more of what is different, not more of the same. – Russell Ackoff

Not only is “maturity” reached by most orgs, it is actively pursued in order to fulfill an unstated, but deeply rooted amygdalayian desire to transition from org to borg. The hilarity of the situation is that while a “maturing” org’s behaviors and processes unceasingly and silently nudge it toward rigid borgdom, the esteemed leadership continuously cries out for innovation. Do as I say, not as I do. D’oh!

Hameltonian Gems

Hameltonian == Hamiltonian, get it? I know, I know – that’s the worst free-association joke you’ve ever heard.

When it comes to eloquently cracking good jokes while talking about serious matters, Gary Hamel is right up there with fellow heretical management genius Russell Ackoff. Check out these gems from Mr. Hamel’s latest book, “What Matters Now“:

- Unfortunately, the groundwater of business is now heavily contaminated with the runoff from morally blinkered egomania.

- It was a perfect storm of human delinquency. Deceit, hubris, myopia, greed, and denial were all luridly displayed.

- “ninja” loans (no income, no job, no assets).

- Among the powerful, blame deflection is a core competence.

- As ethical truants, big business seems to rank alongside Charlie Sheen and Lindsay Lohan.

- If life had adhered to Six Sigma rules, we’d still be slime.

- …they seem to have come from another solar system—one where CFOs are servants rather than gods.

- …you’d have an easier time getting a date with a supermodel or George Clooney than turning your company into an innovation hottie.

- Unlike Apple, most companies are long on accountants and short on artists. They are run by executives who know everything about cost and next to nothing about value.

Whole, Part, Purposeful, Unpurposeful

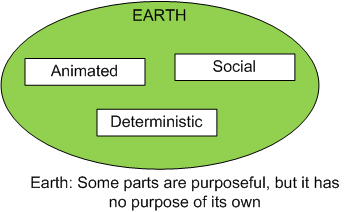

Perhaps ironically, the various branches of “systems thinking” do not have a consensus definition of “system” archetypes. In “Ackoff’s Best”, Russell Ackoff lays down his definition as follows:

There are three basic types of systems and models of them, and a meta-system: one that contains all three types as parts of it. 1. Deterministic: Systems and models in which neither the parts nor the whole are purposeful (e.g. a computer) 2. Animated: Systems and models in which the whole is purposeful but the parts are not (e.g. you or me). 3. Social: Systems and models in which both the parts and the whole are purposeful (e.g. an institution). All three types of systems are contained in ecological systems, some of whose parts are purposeful but not the whole. For example, Earth is an ecological system that has no purpose of its own but contains social and animate systems that do, and deterministic systems that don’t.

But wait! Why are there no Ackoffian systems whose parts are purposeful but whose whole is un-purposeful? Russ doesn’t say why, but BD00 (of course) can speculate.

As soon as one inserts a purposeful part into a deterministic system, the system auto-becomes purposeful?

As soon as one inserts a purposeful part into a deterministic system, the system auto-becomes purposeful?

Complementary Views

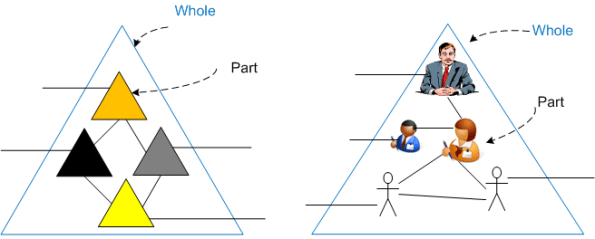

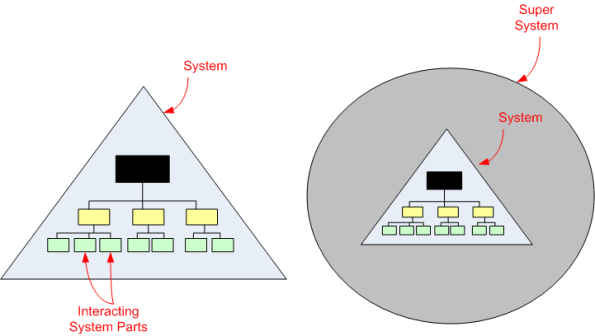

One classic definition of a system is “a set of interacting parts that exhibits emergent behavior not attributable solely to one part“. An alternative, complementary definition of a system served up by Russell Ackoff is “a whole that is defined by its function in a larger system of which it is a part“.

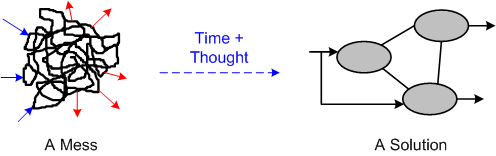

The figure below models the first definition on the left and the second definition on the right. Neither is “righter” than the other. They, and I love saying this because it’s frustratingly neutral, “just are“.

Viewing a system of interest from multiple viewpoints provides the viewer with a more holistic understanding of the system’s what, how, and why. Problem diagnosis and improvement ideas are vastly increased when time is taken to diligently look at a system from multiple viewpoints. Sadly, due to how we are educated, the inculcated tendency of most people is to look at a system from a single, parochial viewpoint: “what’s in it for me?“.

Cracked Up

One of the reasons why I love Russell Ackoff is that he cracks me up even while he writes about depressingly serious matters. Here’s just one example from his bottomless well of wisdom:

Business schools do not teach students how to manage. What they do teach are (1) vocabularies that enable students to speak with authority about subjects they do not understand, and (2) to use principles of management that have demonstrated their ability to withstand any amount of disconfirming evidence. – Russell Ackoff

Want another example? OK, OK, here it is:

“Walk the talk” is futile advice to executives because for them walking and talking are incompatible activities. They can do only one at a time. Therefore, they choose to talk. It takes less effort and thought. – – Russell Ackoff

Messmatiques And Empathic Creators

Assume that you have a wicked problem that needs fixing; a bonafide Ackoffian “mess” or Warfieldian “problematique” – a “messmatique“. Also assume (perhaps unrealistically) that a solution that is optimal in some sense is available:

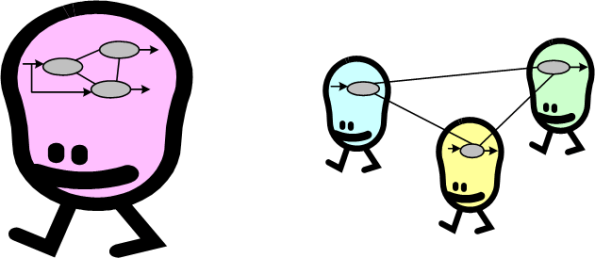

The graphic below shows two different social structures for developing the solution; individual-based and group-based.

If the messmatique is small enough and well bounded, the individual-based “structure” can produce the ideal solution faster because intra-cranial communication occurs at the speed of thought and there is no need to get group members aligned and on the same page.

Group efforts to solve a messmatique often end up producing a half-assed, design-by-committee solution (at best) or an amplified messmatique (at worst). D’oh!

Alas, the individual, genius-based, problem solving structure is not scalable. At a certain level of complexity and size, a singular, intra-cranial created solution can produce the same bogus result as an unaligned group structure.

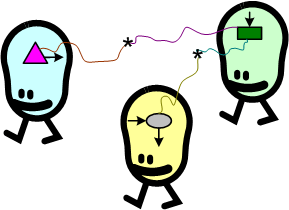

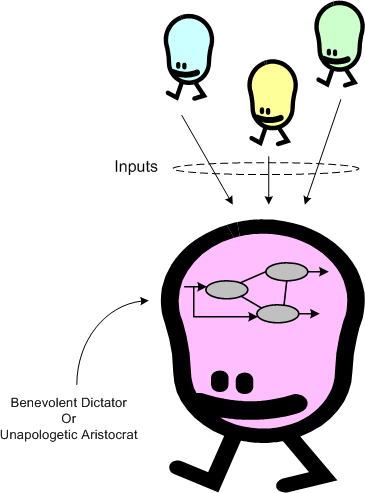

So, how to resolve the dilemma when a messmatique exceeds the capacity of an individual to cope with the beast? How about this hybrid individual+group structure:

Note: The Brooksian BD/UA is not a “facilitator” (catalyst) or a hot shot “manager” (decider). He/she is both of those and, most importantly, an empathic creator.

Composing a problem resolution social structure is necessary but not sufficient for “success“. A process for converging onto the solution is also required. So, with a hybrid individual+group social structure in place, what would the “ideal” solution development process look like? Is there one?

The Principle Objective

The principle objective of a system is what it does, not what its designers, controllers, and/or maintainers say it does. Thus, the principle objective of most corpocratic systems is not to maximize shareholder value, but to maximize the standard of living and quality of work life of those who manage the corpocracy…

The principal objective of corporate executives is to provide themselves with the standard of living and quality of work life to which they aspire. – Addison, Herbert; Ackoff, Russell (2011-11-30). Ackoff’s F/Laws: The Cake (Kindle Locations 1003-1004). Triarchy Press. Kindle Edition.

It seems amazing that the non-executive stakeholders of these institutions don’t point out this discrepancy when the wheels start falling off – or even earlier, when the wheels are still firmly attached. Err, on second thought, it’s not amazing. The 100 year old “system” demands that silence is expected on the matter, no?

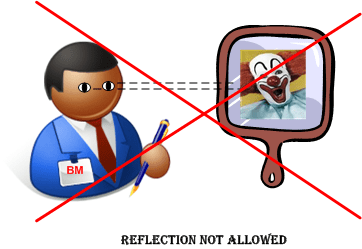

No Reflection

In “Seeing Your Company as a System“, uber systems thinker Russell Ackoff is quoted as saying:

“Experience is not the best teacher; it is not even a good teacher. It is too slow, too imprecise, and too ambiguous.” Organizations have to learn and adapt through experimentation, which he (Ackoff) said “is faster, more precise, and less ambiguous. We have to design systems which are managed experimentally, as opposed to experientially.” – Russell Ackoff

Judging whether an experiment is a success, failure, or something in between, requires the ability to pause and reflect on the results (or lack thereof) being achieved while the experiment is in operation.

In borgs run by self-perceived infallible popes, there is no experimentation and there is no reflection. Orders from above are assumed to be “right” and their execution is never perceived to be an experiment. They are undoubtedly based on an unquestioned, proven theory (usually Theory X) that’s underpinned by a set of rock solid axioms. If success doesn’t manifest as a result of carrying out papal orders, it’s auto-assumed to be the fault of the congregation, or (in less borgy institutions) mysterious supernatural forces beyond papal control. It’s unconscionable to think that the orders themselves were the cause of failure. Why? Because pauses during, and reflection after, execution are not allowed.

What’s On Your List?

In Russell Ackoff‘s “Idealized Design” method, he suggests that designers assume that the system they’re trying to improve/re-design exploded last night and it no longer exists. D’oh! He does this in order to put a jackhammer to the layers of unquestioned, un-noticed, outdated, and hard-wired assumptions that reside in every designer’s mind.

So, if you were part of an emergency task force charged with re-designing your no-longer-existing org, what candidate list of ideas would you concoct? To help jumpstart your underused, but innately powerful creative talents, here’s an outrageous example list that I stole from a raging lunatic:

- Provide two computer monitors for every employee and religiously refresh workstations every three years.

- Provide two projectors and multiple whiteboards in each conference room. Ensure a plentiful supply of working markers. No exclusive executive conference rooms – all rooms equally accessible to all, with negotiated overrides.

- Physically co-locate all product and project teams for the duration. Disallow a rotating door where projectees can come and go as they please or management pleases – with rare exceptions of course.

- Put round tables in every conference room.

- Distribute executive and middle manager offices throughout the org. No bunching in a cloistered, elitist corner, space, or glistening building with HR/Marketing/PR/finance/contracts or other overhead functions.

- Require every manager in the org with direct reports to periodically ask each direct report: “How can I help you do your job better?” at frequent one-on-one meetings. If a manager has too many direct reports – then fix it somehow.

- Require every manager who has managers reporting to him/her to ask each of his/her subordinate managers: “Can you give me an example of how you helped one or more of your direct reports to grow and develop this year?“.

- Require periodic, skip-level manager-subordinate meetings where the manager triggers the conversation and then just listens.

- If “schedule is king” all the time, then write it into your prioritized core values list – just above “engineering excellence and elegant products“. If your core values list contains conflicting values, then prioritize it.

- Carefully and continuously monitor group (not individual) interaction protocols and behaviors. Diligently prevent protocol bloat and convert tightly coupled, synchronous client-server relationships into loosely couple, asynchronous, peer-to-peer exchanges.

- Explicitly budget X days of user-chosen training to every person in the org and enforce the policy’s execution.

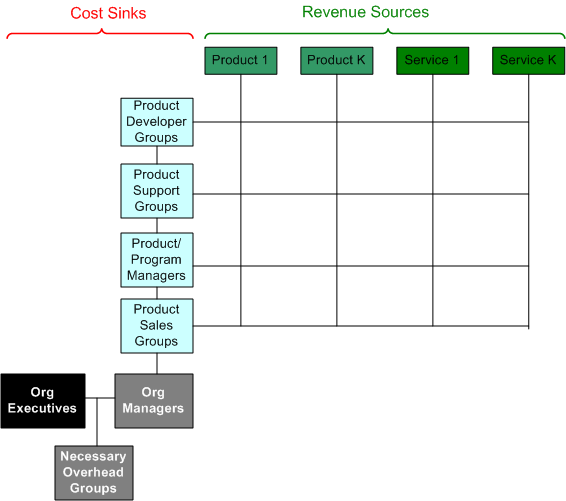

- To reinforce why the org exists and de-emphasize who is “more important” than who, publish a product and/or service-centric org chart with products/services across the top and groups, including all managers, down the side. Preferably, the managers should be on the bottom propping up the org. (See figure below).

- Abandon the “employee-in-a-box” classification and reward system. Pay each person enough so that pay isn’t an issue, and publicly publish all salaries as a self-regulating mechanism.

- Create policy making and problem solving councils up and down the org. Members must consist of three levels of titles and include both affectees in addition to effectors.

- Give leadees a say regarding who their leaders are. Publicly publish all reviews of leaders by leadees.

- Require periodic job rotations to reduce the org’s truck number.

- Frequently survey the entire org for ideas and problem hot spots. Visibly act on at least concern within a relatively short amount of time after each survey.

- Provide every employee with an org credit card and budget a fixed amount of money where no approvals are required for purchases. Fix the purchasing system to make it ridiculously easy for expenses to be submitted.