Archive

The WTF? Metric

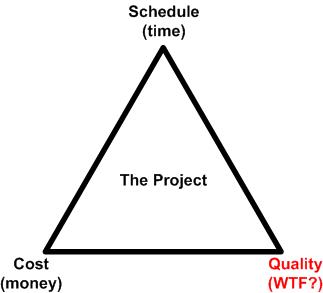

Lo and behold! It’s the monstrously famous iron triangle:

Even though all three critical project factors should be respected equally, BD00 put “schedule” on top because the unspoken rule is “schedule is king” in many orgs.

Everyone who’s ever worked on an important, non-boondoggle, project has heard or spoken words like these:

“I’m concerned that we’re exceeding the budget.”

“I’m afraid that we won’t meet the schedule commitment.”

But how many people have heard words like these:

“I fear that our product quality won’t meet our customer’s expectations.”

Ok, so you have heard them, but stop raining on my parade and let’s not digress.

The reason that quality concerns are mentioned so infrequently relative to cost and schedule is that the latter two objective project attributes are easily tracked by measuring the universally accepted “money” and “time” metrics. There is no single, universally accepted objective quality metric. If you don’t believe BD00, then just ask Robert Pirsig.

To raise quality up to the level of respectability that schedule and cost enjoy, BD00 proposes a new metric for measuring quality: the “WTF?“. To start using the metric, first convince all your people to not be afraid of repercussions and encourage them to blurt out “WTF?” every time they see some project aspect that violates their aesthetic sense of quality. Then, have them doggedly record the number and frequency of “WTF?”s they hear as the project progresses.

Before you know it, you’ll have a nice little histogram to gauge the quality of your project portfolio. Then you’ll be able to…, uh, you’ll be able to… do something with the data?

Any Obstacles?

In Scrum, one of the three questions every team member is supposed to answer at the daily standup meeting is: “Are there any obstacles in your way?“. BD00 often wonders how many people actually answer it, let alone really answer it…

And no, BD00 doesn’t really answer it. Been there and done that. As you might surmise, because of his uncivilized nature and lack of political savvy, it didn’t work out so well – so he stopped using that industry-best practice. But for you and your team, really answering the question works wonders – right?

The day soldiers stop bringing you their problems is the day you have stopped leading them. They have either lost confidence that you can help or concluded that you don’t care. Either case is a failure of leadership.” – Karl Popper

Burn Baby Burn

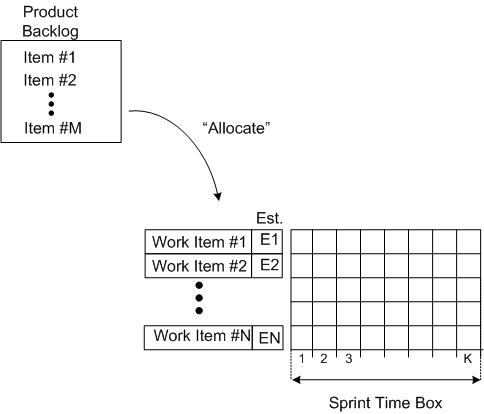

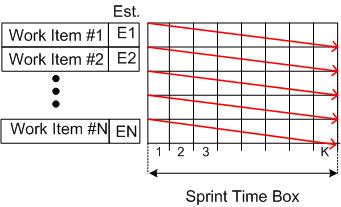

The “time-boxed sprint” is one of the star features of the Scrum product development process framework. During each sprint planning meeting, the team estimates how much work from the product backlog can be accomplished within a fixed amount of time, say, 2 or 4 weeks. The team then proceeds to do the work and subsequently demonstrate the results it has achieved at the end of the sprint.

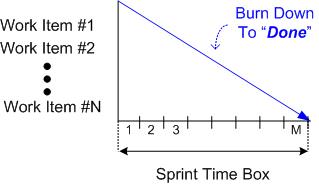

As a fine means of monitoring/controlling the work done while a sprint is in progress, some teams use an incarnation of a Burn Down Chart (BDC). The BDC records the backlog items on the ordinate axis, time on the abscissa axis, and progress within the chart area.

The figure below shows the state of a BDC just prior to commencing a sprint. A set of product backlog items have been somehow allocated to the sprint and the “time to complete” each work item has been estimated (Est. E1, E2….).

At the end of the sprint, all of the tasks should have magically burned down to zero and the BDC should look like this:

So, other than the shortened time frame, what’s the difference between an “agile” BDC and the hated, waterfall-esque, Gannt chart? Also, how is managing by burn down progress any different than the hated, traditional, Earned Value Management (EVM) system?

So, other than the shortened time frame, what’s the difference between an “agile” BDC and the hated, waterfall-esque, Gannt chart? Also, how is managing by burn down progress any different than the hated, traditional, Earned Value Management (EVM) system?

I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by – Douglas Adams

In practice, which of the outcomes below would you expect to see most, if not all, of the time? Why?

We need to estimate how many people we need, how much time, and how much money. Then we’ll know when we’re running late and we can, um, do something.

Fluency And Maturity

After reading about Martin Fowler‘s “levels of agile fluency”, I decided to do a side-by-side exploration of his four levels of fluency with the famous (infamous?) five “levels of CMMI maturity“:

As you can easily deduce, the first difference that I noticed was that

The SEI focuses on the process. Fowler focuses on the team of people.

Next, I noticed:

To the SEI, “proactive” is good and “reactive” is bad. Proactive vs. reactive seems to be a “don’t care” to Fowler.

The SEI emphasizes the attainment of “control“. Fowler emphasizes the attainment of “business value“.

While writing this post, I really wanted to veer off into a rant demonizing the SEI list for being so mechanistically Newtonian. However, I stepped back, decided to take the high road, and formed the following meta-conclusion:

The SEI & Fowler lists aren’t necessarily diametrically opposed.

Perhaps the nine levels can be intelligently merged into a brilliant hybrid that balances both people and process (like the Boehm/Turner attempt).

What do you think? Is the side-by-side comparison fair, or is it an apple & oranges monstrosity?

Shortcutting The Shortcut

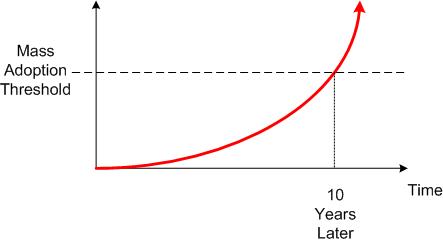

BD00 has heard from several sources that it takes about 10 years for a winning technology to make it into the mainstream. After starting off with a slow uptake due to fear and uncertainty, the floodgates open up and everybody starts leveraging the technology to make more money and greater products.

This 10 year rule of thumb surely applies to the “agile” movement, which recently celebrated its 10th anniversary. But as the new book below shows, the frenzy can get laughably outta control.

Not to rag too much on Mr. Goldstein, but sheesh. As if Scrum is not “fast” enough already? Now we’re patronizingly told that we need “intelligent” shortcuts to make it even faster. Plus, we idiots need to learn what these shortcuts are and how to apply them in a “step-by-step” fashion from a credentialed sage-on-a-stage. Hey, we must be idjets cuz, despite the beautiful simplicity of Scrum, Mr. Goldstein implies that we keep screwing up its execution.

As usual, BD00 hasn’t read the ground breaking new book. And he has no plan to read it. And he has no plan to stop writing about topics he hasn’t researched “deeply“. Thus, keep reminding yourself that:

One Step Forward, N-1 Steps Back

For the purpose of entertainment, let’s assume that the following 3-component system has been deployed and is humming along providing value to its users:

Next, assume that a 4-sprint enhancement project that brought our enhanced system into being has been completed. During the multi-sprint effort, several features were added to the system:

OK, now that the system has been enhanced, let’s say that we’re kicking back and doing our project post-mortem. Let’s look at two opposite cases: the Ideal Case (IC) and the Worst Case (WC).

First, the IC:

During the IC:

- we “embraced” change during each work-sprint,

- we made mistakes, acknowledged and fixed them in real-time (the intra-sprint feedback loops),

- the work of Sprint X fed seamlessly into Sprint X+1.

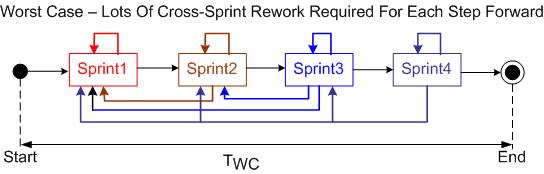

Next, let’s look at what happened during the WC:

Like the IC, during each WC work-sprint:

- we “embraced” change during each work-sprint,

- we made mistakes, acknowledged and fixed them in real-time (the intra and inter-sprint feedback loops),

- the work of Sprint X fed seamlessly into Sprint X+1.

Comparing the IC and WC figures, we see that the latter was characterized by many inter-sprint feedback loops. For each step forward there were N-1 steps backward. Thus, TWC >> TIC and $WC >> $IC.

WTF? Why were there so many inter-sprint feedback loops? Was it because the feature set was ill-defined? Was it because the in-place architecture of the legacy system was too brittle? Was it because of scope creep? Was it because of team-incompetence and/or inexperience? Was it because of management pressure to keep increasing “velocity” – causing the team to cut corners and find out later that they needed to go back often and round those corners off?

So, WTF is the point of this discontinuous, rambling post? I dunno. As always, I like to make up shit as I go.

After-the-fact, I guess the point can be that the same successes or dysfunctions can happen during the execution of an agile project or during the execution of a project executed as a series of “mini-waterfalls“:

- ill-defined requirements/features/user-stories/function-points/use-cases (whatever you want to call them)

- working with a brittle, legacy, BBOM

- team incompetence/inexperience

- scope creep

- schedule pressure

Ultimately, the forces of dysfunction and success are universal. They’re independent of methodology.

The Least Used Option

“We need to estimate how many people we need, how much time, and how much money. Then we’ll know when we’re running late and we can, um, do something.”

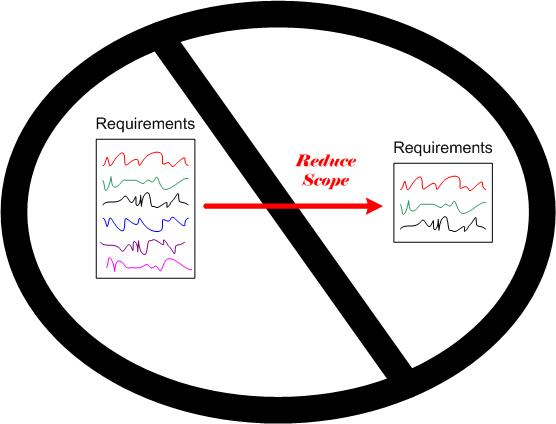

OK, assuming we are indeed running late and, as ever, “schedule is king“. WTF are our options?

- We can add more people.

- We can explicitly or (preferably) implicitly impose mandatory overtime; paid or (preferably) unpaid.

- We can reduce the project scope.

The least used option, because it’s the only one that would put management in an uncomfortable position with the customer(s), is the last one. This, in spite of the fact that it is the best option for the team’s well being over both the short and long term.

Agile Overload

Since I buy a lot of Kindle e-books, Amazon sends me book recommendations all the time. Check out this slew of recently suggested books:

My fave in the list is “Agile In A Flash“. I’d venture that it’s written for the ultra-busy manager on-the-go who can become an agile expert in a few hours if he/she would only buy and read the book. What’s next? Agile Cliff notes?

“Agile” software development has a lot going for it. With its focus on the human-side of development, rapid feedback control loops to remove defects early, and its spirit of intra-team trust, I can think of no better way to develop software-intensive systems. It blows away the old, project-manager-is-king, mechanistic, process-heavy, and untrustful way of “controlling” projects.

However, the word “agile” has become so overloaded (like the word “system“) that….

Everyone is doing agile these days, even those that aren’t – Scott Ambler

Gawd. I’m so fed up with being inundated with “agile” propaganda that I can’t wait for the next big silver bullet to knock it off the throne – as long as the new king isn’t centered around the recently born, fledgling, SEMAT movement.

What about you, dear reader? Do you wish that the software development industry would move on to the next big thingy so we can get giddily excited all over again?

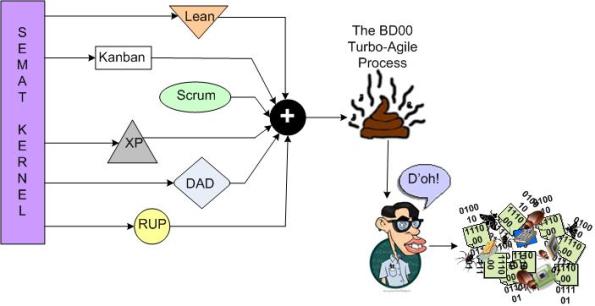

Going Turbo-Agile

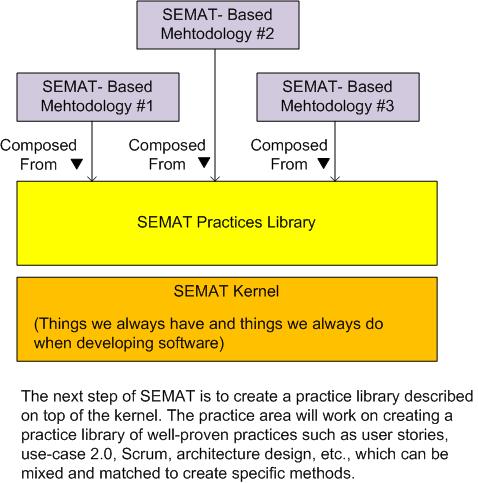

I’m planning on using the state of the art SEMAT kernel to cherry-pick a few “best practices” and concoct a new, proprietary, turbo-agile software development process. The BD00 Inc. profit deluge will come from teaching 1 hour certification courses all over the world for $2000 a pop. To fund the endeavor, I’m gonna launch a Kickstarter project.

What do you think of my slam dunk plan? See any holes in it?

Revolution, Or Malarkey?

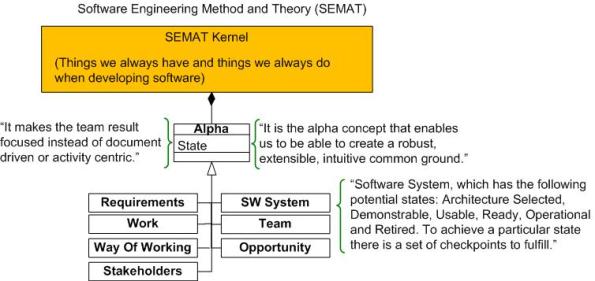

BD00 has been following the development of Ivar Jacobson et al’s SEMAT (Software Engineering Method And Theory) work for a while now. He hasn’t decided whether it’s a revolutionary way of thinking about software development or a bunch of pseudo-academic malarkey designed to add funds to the pecuniary coffers of its creators (like the late Watts Humphrey’s, SEI-backed, PSP/TSP?).

To give you (and BD00!) an introductory understanding of SEMAT basics, he’s decided to write about it in this post. The description that follows is an extracted interpretation of SEMAT from Scott Ambler‘s interview of Ivar: “The Essence of Software Engineering: An Interview with Ivar Jacobson”.

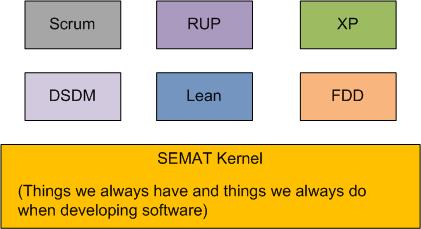

As the figure below shows, the “kernel” is the key concept upon which SEMAT is founded (note that all the boasts, uh, BD00 means, sentences, in the graphic are from Ivar himself).

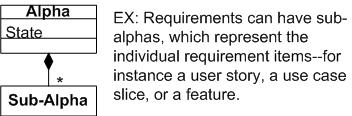

In its current incarnation, the SEMAT kernel is comprised of seven, fundamental, widely agreed-on “alphas“. Each alpha has a measurable “state” (determined by checklist) at any time during a development endeavor.

At the next lower level of detail, SEMAT alphas are decomposed into stateful sub-alphas as necessary:

As the diagram below attempts to illustrate, the SEMAT kernel and its seven alphas were derived from the common methods available within many existing methodologies (only a few representative methods are shown).

In the eyes of a SEMATian, the vision for the future of software development is that customized methods will be derived from the standardized (via the OMG!) kernel’s alphas, sub-alphas, and a library of modular “practices“. Everyone will evolve to speak the SEMAT lingo and everything will be peachy keen: we’ll get more high quality software developed on time and under budget.

OK, now that he’s done writing about it, BD00 has made an initial assessment of the SEMAT: it is a bunch of well-intended malarkey that smacks of Utopian PSP/TSP bravado. SEMAT has some good ideas and it may enjoy a temporary rise in popularity, but it will fall out of favor when the next big silver bullet surfaces – because it won’t deliver what it promises on a grand scale. Of course, like other methodology proponents, SEMAT’s advocates will tout its successes and remain silent about its failures. “If you’re not succeeding, then you’re doing it wrong and you need to hire me/us to help you out.”

But wait! BD00 has been wrong so many times before that he can’t remember the last time he was right. So, do your own research, form an opinion, and please report it back here. What do you think the future holds for SEMAT?