Archive

Traceability Woes

For safety-critical systems deployed in aerospace and defense applications where people’s lives may at be at stake, traceability is often talked about but seldom done in a non-superficial manner. Usually, after talking up a storm about how diligent the team will be in tracing concrete components like source code classes/functions/lines and hardware circuits/boards/assemblies up the spec tree to the highest level of abstract system requirements, the trace structure that ends up being put in place is often “whatever we think we can get by with for certification by internal and external regulatory authorities“.

I don’t think companies and teams willfully and maliciously screw up their traceability efforts. It’s just that the pragmatics of diligently maintaining a scrutable traceability structure from ground zero back up into the abstract requirements cloud gets out of hand rather quickly for any system of appreciable size and complexity. The number of parts, types of parts, interconnections between parts, and types of interconnections grows insanely large in the blink of an eye. Manually creating, and more importantly, maintaining, full bottom-to-top traceability evidence in the face of the inevitable change onslaught that’s sure to arise during development becomes a huge problem that nobody seems to openly acknowledge. Thus, “games” are played by both regulators and developers to dance around the reality and pass audits. D’oh!

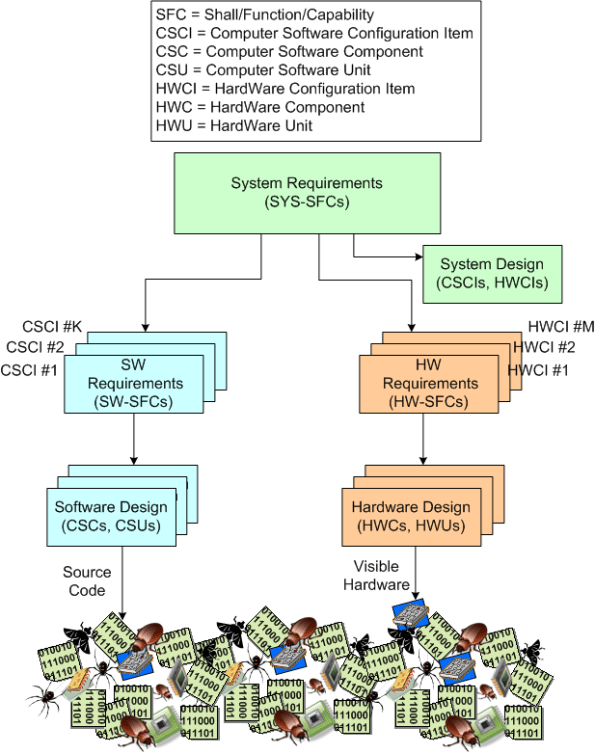

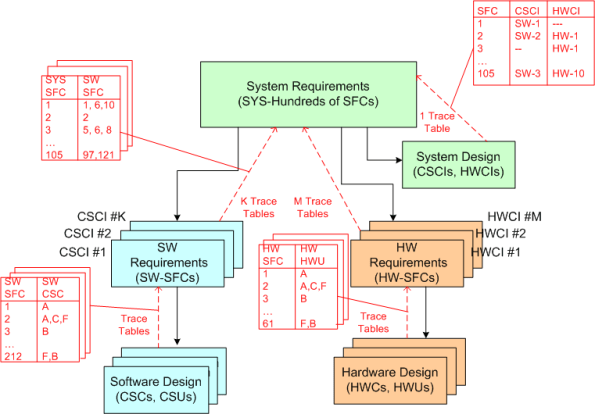

To illustrate the difficulty of the traceability challenge, observe the specification tree below. During the development, the tree (even when agile and iterative feedback loops are included in the process) grows downward and the number of parts that comprise the system explodes.

In “theory” as the tree expands, multiple traceability tables are rigorously created in pay-as-you-go fashion while the info and knowledge and understanding is still fresh in the minds of the developers. When “done” (<- LOL!), an inverse traceability tree with explicit trace tables connecting levels like the example below is supposed to be in place so that any stakeholder can be 100% certain that the hundreds of requirements at the top have been satisfied by the thousands of “cleanly” interconnected parts on the bottom. Uh yeah, right.

Focus And Curiosity

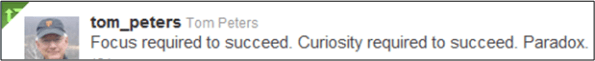

I like using tweets as a source of blog posts. This one by Tom Peters captured my imagination:

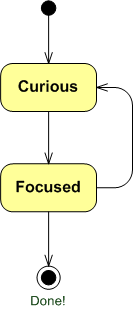

Too much vertical focus and there’s no growth or development. Too much horizontal curiosity and there’s no accomplishment. However, the right mix of focus and curiosity provides for both personal growth and accomplishment. As the state transition diagram below illustrates, I always start a new software project in the curious state of “not knowing“. I then transition into the focused state and cycle between the two states until I’m “done“. Don’t ask me how I decide when to transition from one state to the other because I don’t have a good answer. It’s a metaphysical type of thingy.

I start off in the curious state to gain an understanding of the context, scope, and boundaries of my responsibilities and what needs to be done before diving into the focused state. I’ve learned that when I dive right into the focused state without passing through the curious state first, I make a ton of mistakes that always come back to haunt me in the form of unnecessary rework. I make fewer and less serious mistakes when I enter the curious state at “bootup“. How about you?

Since bozo managers in CCH CLORGS are paid to get projects done through others, they implicitly or explicitly assume that there is no need for a curious state and they exert pressure on their people to start right right out in the focused state – and never leave it.

Good managers, of course, don’t do this because they understand the need for the curious state and that dwelling in it from time to time reduces schedule and increases end product quality. Great managers not only are clued into the fact that the curious state is needed at startup and from time to time post-startup, they actually roll up their sleeves and directly help to establish the context, scope, and boundaries of what needs to be done for each and every person on the project. How many of these good and great managers do you know?

“If I had an hour to save the world, I would spend 59 minutes defining the problem and one minute finding solutions” – Albert Einstein

Don’t you think Mr. Einstein spent a lot of time in the curious state?

Formal Review Chain

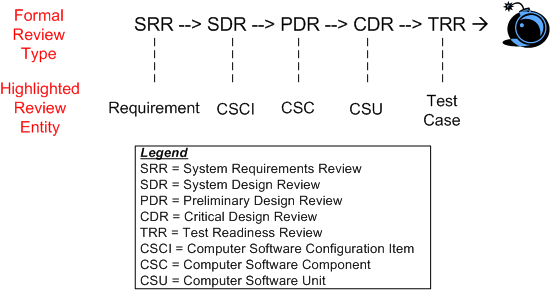

On big, multi-year, multi-million dollar software development projects, a series of “high-ceremony” formal reviews are almost always required to be held by contract. The figure below shows the typical, sequential, waterfall review lineup for a behemoth project.

The entity below each high ceremony review milestone is “supposedly” the big star of the review. For example, at SDR, the structure and behavior of the system in terms of the set of CSCIs that comprise the “whole” are “supposedly” reviewed and approved by the attendees (most of whom are there for R&R and social schmoozing). It’s been empirically proven that the ratio of those “involved” to those “responsible” at reviews in big projects is typically 5 to 1 and the ratio of those who understand the technical content to those who don’t is 1 to 10. Hasn’t that been the case in your experience?

The figure below shows a more focused view of the growth in system artifacts as the project supposedly progresses forward in the fantasy world of behemoth waterfall disasters, uh, I mean projects. Of course, in psychedelic waterfall-land, the artifacts of any given stage are rigorously traceable back to those that were “designed” in the previous stage. Hasn’t that been the case in your experience?

In big waterfall projects that are planned and executed according to the standard waterfall framework outlined in this post, the outcome of each dog-and-pony review is always deemed a great success by both the contractee and contractor. Backs are patted, high fives are exchanged, and congratulatory e-mails are broadcast across the land. Hasn’t that been the case in your experience?

Cakeless

Assume that you have two product development teams toiling away. One finishes early and the other blows right past its schedule – finally finishing the work waaay downstream.

I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by – Douglas Adams

Do you think that managers at DYSCOs ignore the early finishers and reward the laggards with a cake party for the team’s “heroic effort down the stretch“? Either that happens, or all projects finish behind schedule and over budget….. and nobody gets any cake. Bummer.

Taking Stock

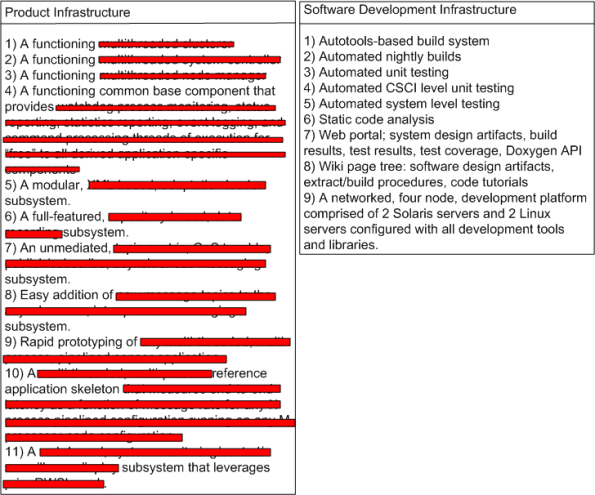

Every once in awhile, it’s good to step back and take stock of your team’s accomplishments over a finite stretch of time. I did this recently, and here’s the marketing hype that I concocted:

I like to think of myself as a pretty open dude, but I don’t think I’m (that) stupid. The product infrastructure features have been redacted just in case one of the three regular readers of this blasphemous blog happens to be an evil competitor who is intent on raping and pillaging my company.

The team that I’m very grateful to be working on did all this “stuff” in X months – starting virtually from scratch. Over the course of those X months, we had an average of M developers working full time on the project. At an average cost of C dollars per developer-month, it cost roughly X * M * C = $ to arrive at this waypoint. Of course, I (roughly) know what X, M, C, and $ are, but as further evidence that I’m not too much of a frigtard (<- kudos to Joel Spolsky for adding this term of endearment to my vocabulary!), I ain’t tellin’.

So, what about you? What has your team accomplished over a finite period of time? What did it cost? If you don’t know, then why not? Does anyone in your group/org know?

Apples And Oranges

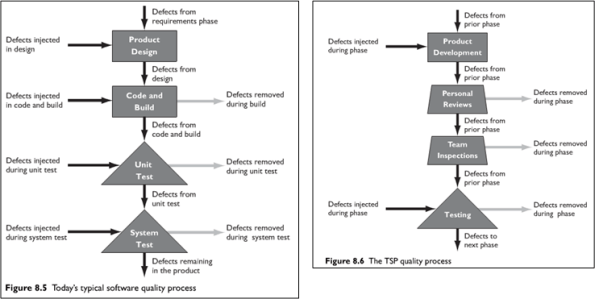

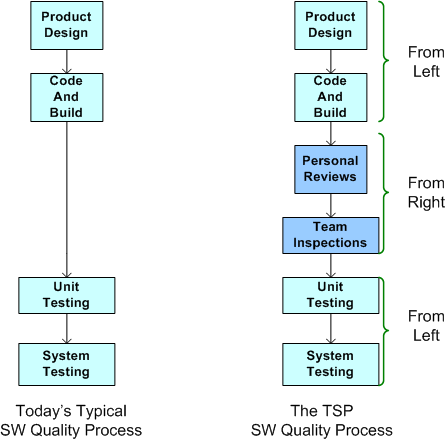

In “Leadership, Teamwork, and Trust“, Watts Humphrey and James Over build a case against the classic “Test To Remove Defects” mindset (see the left portion of the figure below). They assert that testing alone is not enough to ensure quality – especially as software systems grow larger and commensurately more complex. Their solution to the problem (shown on the right of the figure below) calls for more reviews and inspections, but I’m confused as to when they’re supposed to occur: before, after, or interwoven with design/coding?

If you compare the left and right hand sides of the figure, you may have come to the same conclusion as I have: it seems like an apples to oranges comparison? The left portion seems more “concrete” than the right portion, no? Since they’re not enumerated on the right, are the “concrete” design and code/build tasks shown on the left subsumed within the more generic “Product Development” box on the right?

In order to un-confuse myself, I generated the equivalent of the Humphrey/Over TSP (Team Software Process) quality process diagram on the right using the diagram on the left as the starting reference point. Here’s the resulting apples-to-apples comparison:

If this is what Humphrey and Over meant, then I’m no longer confused. Their TSP approach to software quality is to supplement unit and system testing with reviews and inspections before testing occurs. I wish they said that in the first place. Maybe they did, but I missed it.

If this is what Humphrey and Over meant, then I’m no longer confused. Their TSP approach to software quality is to supplement unit and system testing with reviews and inspections before testing occurs. I wish they said that in the first place. Maybe they did, but I missed it.

I’ll Have A Double, Please

Tested And Untested

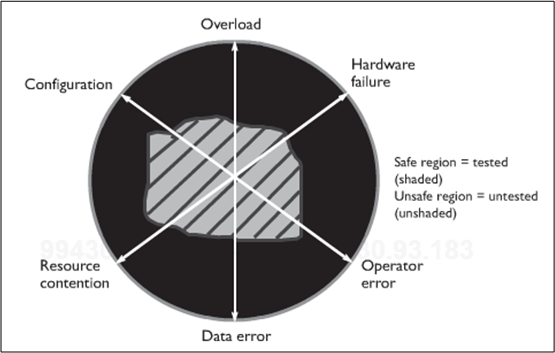

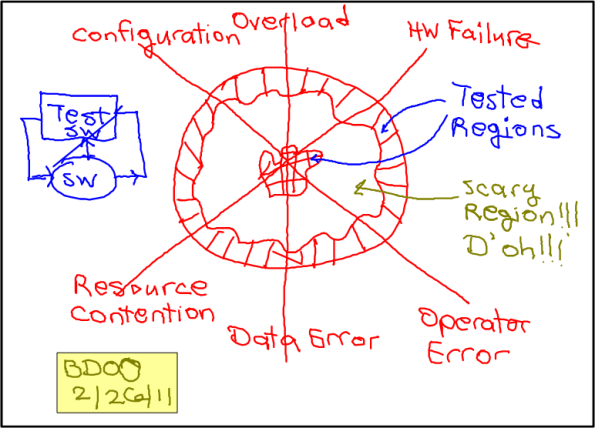

Being the e-klepto that I am, I stole this kool graphic from Humphrey and Over’s book “Leadership, Teamwork, And Trust“:

It represents the tested-to-untested (TU) region ratio of a generic, big software system. Humphrey/Over use it to prove that the ubiquitous, test-centric approach to quality doesn’t work very well and that by focusing on defect prevention via upfront review/inspection before testing, one can dramatically decrease the risk for any given TU ratio. Hard to argue with that, right?

The point I’d like to make, which is different than the one Humphrey/Over focus on in their book (to sell their heavyweight PSP/TSP methodology, of course), is that when a software system is released into the wild, it most likely hasn’t been tested in the wacky configurations and states that can cause massive financial loss and/or personal injury. You know, those “stressful” system states on the edge of chaos where transient input overloads occur, or hardware failures occur, or corrupted data enters the system. I think building the test infrastructure that can duplicate these doomsday scenarios – and then actually testing how the system responds in these rare but possible environments is far more effective than just adding political dog-and-pony reviews/inspections to one’s approach to quality. Instead of decreasing the risk for a fixed TU ratio, which reviews/inspections can achieve (if (and it’s a big if) they’re done right), it increases the TU ratio itself. However, since system-specific test tools are unglamorous and perceived as unnecessary costs by scrooge managers more concerned about their image than other stakeholders, scarily untested software is foisted upon the populace at an increasing rate. D’oh!

Note: The dorky hand made drawing above is the first one that I created with the $14.99 “Paper Tablet” app for my Livescribe Echo smartpen. “Paper Tablet” turns a notebook page into a surrogate computer tablet. When I run an “ink aware” app like Microsoft Visio, and then physically draw on a notebook page, the output goes directly to the computer app and it shows up on the screen – in addition to being stored in the pen. Thus, as I was drawing this putrid picture with my pen, it was being simultaneously regenerated on a visio page in real-time (see clip below). Kool, eh? Maybe with some practice……

Over The Wall

The figure below shows the perceived relative importance of groups in a typical corpricracy. The DICs, because they do the nasty stuff called work, are on the bottom. The R&D staff, because they are academically smarter than the DICsters, are next in line. Management, because….. they are managers, are of the utmost importance. Because of language differences and the entrenched graded scale of importance, there are huge communication gaps between the players in the “system“.

Now that the context has been established, let’s look at the dynamic interactions that take place (if they even do take place) between the R&D and product groups. On the left of the latest dorky Bulldozer00 figure below, we have the classic and ubiquitous “over the wall“, one way anti-pattern of excellence. New product and product enhancement gibberish gets tossed over the barrier and taken out to the trash. Meanwhile, like that liquid metal dude in Terminator II, the once vibrant product line freezes in place and competitors race ahead. Syonara dude.

An alternative way of birthing new products and imbuing aging product lines with promising technology enhancements is to temporarily rotate and embed members of the two groups within each other’s sterile environment. Of course, this alternative way of doin’ b’ness is rarely observed in the wild because it would disrupt the pyramid of importance and force members of one guild to learn the language and customs of the other – which is verboten! Meanwhile, Rome burns.

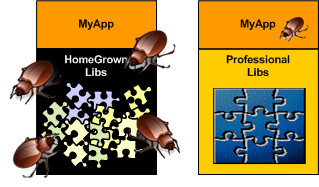

Where’s The Bug?

When you’re designing and happily coding away in the application layer and you discover a nasty bug, don’t you hate it when you find that the chances are high that the critter may not be hiding in your code – it may be in one of the cavernous homegrown libraries that prop your junk up. I hate when that happens because it forces me to do a mental context switch from the value-added application layer down into the support layer(s) – sometimes for days on end (ka-ching, ka-ching; tic-toc, tic-toc).

Compared to writing code on top of an undocumented, wobbly, homegrown BBoM, writing code on top of a professionally built infrastructure with great tutorials and API artifacts is a joy. When you do find a bug in the code base, the chances are astronomically high that it will be in your code and not down in the infrastructure. Unsurprisingly, preferring the professional over the amateur saves time, money, and frustration.

For the same strange reason (hint: ego) that command and control hierarchy is accepted without question as the “it just has to be this way” way of structuring a company for “success“, software developers love to cobble together their own BBoM middleware infrastructure. To reinforce this dysfunctional approach, managers are loathe to spend money on battle-tested middleware built by world class experts in the field. Yes, these are the same managers who’ll spend $100K on a logic analyzer that gets used twice a year by the two hardware designer dudes that cohabitate with the hundreds of software weenies and elite BMs inside the borg. C’est la vie.