Archive

A Skeptical “No”

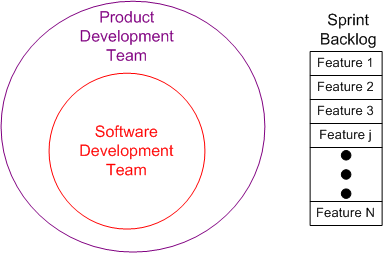

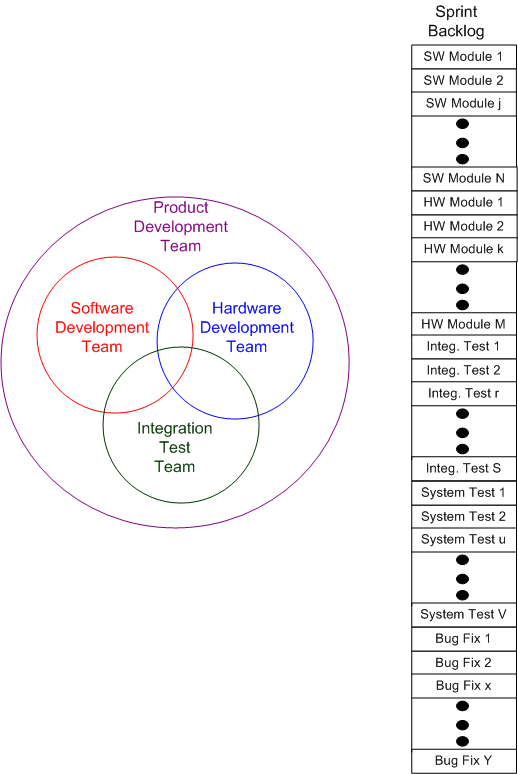

Just about every agile video, book, and article I’ve ever consumed assumes some variant of the underlying team model shown below. The product these types of teams build is comprised of custom software running on off-the-shelf server hardware. Even though it’s not shown, they also assume a client-server structure, request-response protocol, database-centric system.

The team model for the types of systems I work on is given below. They are distributed real-time event systems comprised of embedded, heterogeneous, peer processors glued together via a pub-sub protocol. By necessity, specialized, multi-disciplinary teams are required to develop this category of systems. Also, by necessity, the content of the sprint backlog is more complex and intricately subtler than the typical agile IT product backlog of “features” and “user stories“.

When I watch/read/listen to smug agile process experts and coaches expound the virtues of their favorite methodology using narrow, anecdotal, personal stories from the database-centric IT world, I continuously ask myself “can this apply to the type of products I help build?“. Often, the answer is a skeptical “no“. Not always, but often.

Where To Start?

The purpose of abstraction is not to be vague, but to create a new semantic level in which one can be absolutely precise. — Edsger Dijkstra

With Edsger’s delicious quote in mind, let’s explore seven levels of abstraction that can be used to reason about big, distributed, systems:

At level zero, we have the finest grained, most concrete unit of design, a single puny line of “source code“. At level seven, we have the coarsest grained, most abstract unit of design, the mysterious and scary “system” level. A line of code is simple to reason about, but a “system” is not. Just when you think you understand what a system does, BAM! It exhibits some weird, perhaps dangerous, behavior that is counter-intuitive and totally unexpected – especially when humans are the key processing “nodes” in the beast.

Here are some questions to ponder regarding the seven level stack: Given that you’re hired to build a big, distributed system, at what level would you start your development effort? Would you start immediately coding up classes using the much revered TDD “best practice” and let all the upper levels of abstraction serendipitously “emerge”? Relatively speaking, how much time “up front” should you spend specifying, designing, recording, communicating the structures and behaviors of the top 3 levels of the stack? Again, relatively speaking, how much time should be allocated to the unit, integration, functional, and system levels of testing?

Formal Waterfall Events

If ur customer *requires* formal waterfall events like “Sys Reqs Review”, “Prelim Design Review”, “Critical Design Review”, gotta do them.

— Tony DaSilva (@Bulldozer0) March 30, 2014

The customers of all the big government-financed sensor system programs I’ve ever worked on have required the aforementioned, waterfall, dog-and-pony shows as part of their well-entrenched acquisition process. Even prior to commencing a waterfall death march, as part of the pre-win bidding process, customers also (still) require contractors to provide detailed schedule and cost commitments in their proposal submissions – right down to the CSCI level of granularity.

If you think it’s tough to get your internal executive customers to wholeheartedly embrace an “agile adoption” or “no estimates” initiative, try to wrap your mind around the cosmic difficulty of doing the same to a large, fragmented, distributed authority, external acquisition machine whose cogs are fine-tuned to: cover their ass, defend their turf, and doggedly fight to keep the extant process that justifies their worth in place. Good luck with that.

Trivial Trivia

I was going through some old project stuff and stumbled upon the chart below. I developed it back when I was the software lead of a nine person sub-team on an embedded system product development effort:

Putting all those indecipherable acronyms adorning the chart aside, note that the project was performed in 2004 – a mere 3 years after the famous “Agile Manifesto” was hatched. I can’t remember if I knew about (or read) the manifesto at the time, but I do know that Tom Gilb’s “Evo“ and Barry Boehm’s “Spiral“ processes had radically changed my worldview of software development. Specifically, the (now-obvious) concept of incremental development and delivery rang my bell as the best way to mitigate risk on challenging, software-intensive, projects.

As the chart illustrates, the actual hand-off of each of the seven builds (to the system integration test team) was pretty much dead nuts right on target. Despite the fact that the project front end (requirements definition and software design) was managed as a “waterfall” endeavor, the targets were met. Thus, I’m led to believe the following trivial trivia:

Not all agile projects succeed and not all waterfall projects fail.

Dueling Quagmires

To BD00, the agile movement, even though it is a refreshing backlash against the “Process Models And Standards Quagmire” (PMASQ) perpetrated by a well-meaning but clueless mix of government and academic borgs who don’t have to create and build anything, has spawned its own quagmire of “Agile Process Frameworks And Practices Quagmire” (APFAPQ). Like the PMASQ community has ignited a cottage industry of expensive consultants, certifiers, assessors, trainers, and auditors, the APFAPQ movement has jump-started an equivalent community of expensive consultants, coaches, trainers, certifiers.

Government Governance

The figure below highlights one problem with government “governance” of big software systems development. Sure, it’s dated, but it drives home the point that there’s a standards quagmire out there, no?

Imagine that you’re a government contractor and, for every system development project you “win“, you’re required to secure “approval” from a different subset of authorities in a quagmire standards “system” like the one above. Just think of the overhead cost needed to keep abreast of, to figure out which, and to comply with, the applicable standards your product must conform to. Also think of the cost to periodically get your company and/or its products assessed and/or certified. If you ever wondered why the government pays $1000 for a toilet seat, look no further.

I look at this random, fragmented standards diagram as a paranoid, cover-your-ass strategy that government agencies can (and do) whip out when big systems programs go awry: “The reason this program is in trouble is because standards XXX and YYY were not followed“. As if meeting a set of standards guarantees robust, reliable, high-performing systems. What a waste. But hey, it’s other people’s money (yours and mine), so no problemo.

Understood, Manageable, And Known.

Our sophistication continuously puts us ahead of ourselves, creating things we are less and less capable of understanding – Nassim Taleb

It’s like clockwork. At some time downstream, just about every major weapons system development program runs into cost, schedule, and/or technical performance problems – often all three at once (D’oh!).

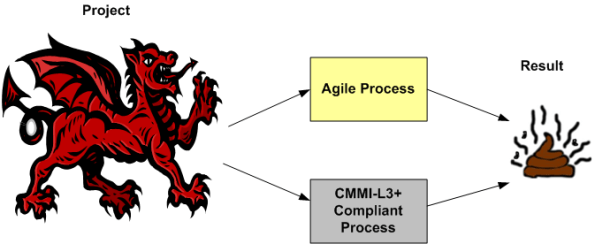

Despite what their champions espouse, agile and/or level 3+ CMMI-compliant processes are no match for these beasts. We simply don’t have the know how (yet?) to build them efficiently. The scope and complexity of these Leviathans overwhelms the puny methods used to build them. Pithy agile tenets like “no specialists“, “co-located team“, “no titles – we’re all developers” are simply non-applicable in huge, multi-org programs with hundreds of players.

Being a student of big, distributed system development, I try to learn as much about the subject as I can from books, articles, news reports, and personal experience. Thanks to Twitter mate @Riczwest, the most recent troubled weapons system program that Ive discovered is the F-35 stealth fighter jet. On one side, an independent, outside-of-the-system, evaluator concludes:

The latest report by the Pentagon’s chief weapons tester, Michael Gilmore, provides a detailed critique of the F-35’s technical challenges, and focuses heavily on what it calls the “unacceptable” performance of the plane’s software… the aircraft is proving less reliable and harder to maintain than expected, and remains vulnerable to propellant fires sparked by missile strikes.

On the other side of the fence, we have the $392 billion program’s funding steward (the Air Force) and contractor (Lockheed Martin) performing damage control via the classic “we’ve got it under control” spiel:

Of course, we recognize risks still exist in the program, but they are understood and manageable. – Air Force Lieutenant General Chris Bogdan, the Pentagon’s F-35 program chief

The challenges identified are known items and the normal discoveries found in a test program of this size and complexity. – Lockheed spokesman Michael Rein

All of the risks and challenges are understood, manageable, known? WTF! Well, at least Mr. Rein got the “normal” part right.

In spite of all the drama that takes place throughout a large system development program, many (most?) of these big ticket systems do eventually get deployed and they end up serving their users well. It simply takes way more sweat, time, and money than originally estimated to get it done.

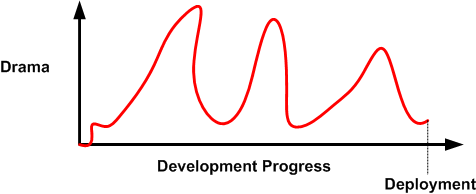

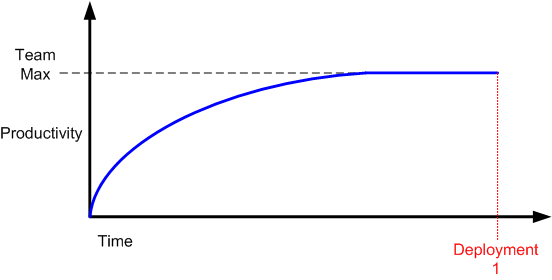

The Drooping Progress Syndrome

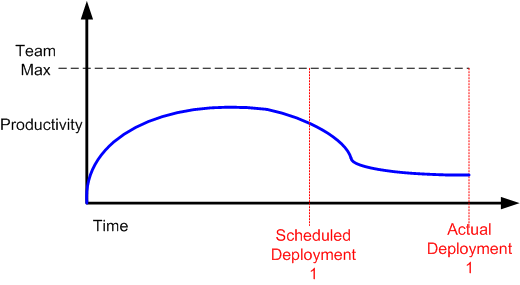

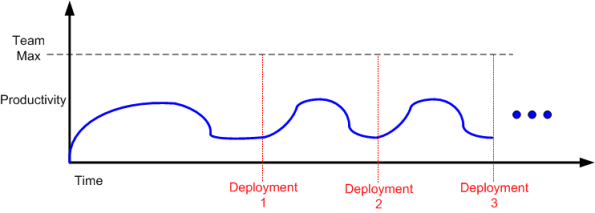

When a new product development project kicks off, nobody knows squat and there’s a lot of fumbling going on before real progress starts to accrue. As the hardware and software environment is stitched into place and initial requirements/designs get fleshed out, productivity slowly but surely rises. At some point, productivity (“velocity” in agile-ese) hits a maximum and then flattens into a zero slope, team-specific, cadence for the duration. Thus, one could be led to believe that a generic team productivity/progress curve would look something like this:

In “The Year Without Pants“, Scott Berkun destroys this illusion by articulating an astute, experiential, observation:

In “The Year Without Pants“, Scott Berkun destroys this illusion by articulating an astute, experiential, observation:

This means that at the end of any project, you’re left with a pile of things no one wants to do and are the hardest to do (or, worse, no one is quite sure how to do them). It should never be a surprise that progress seems to slow as the finish line approaches, even if everyone is working just as hard as they were before. – Scott Berkun

Scott may have forgotten one class of thing that BD00 has experienced over his long and un-illustrious career – things that need to get done but aren’t even in the work backlog when deployment time rolls in. You know, those tasks that suddenly “pop up” out of nowhere (BD00 inappropriately calls them “WTF!” tasks).

Nevertheless, a more realistic productivity curve most likely looks like this:

If you’re continuously flummoxed by delayed deployments, then you may have just discovered why.

Related articles

- The Year Without Pants: An interview with author Scott Berkun (oldienewbies.wordpress.com)

- Scott Berkun Shares Advice for Writers Working Remotely (mediabistro.com)

- A Book in 5 Minutes: “The Year without Pants: WordPress.com and the Future of Work” (tech.co)

A Bureaucrat’s Dream

Thanks to powerful, vested interests and ignorant leadership, some stodgy dinosaur orgs still cling to a bevy of high-falutin’, delay-inducing, product conception/development/maintenance processes. Because of the strong nuclear forces in place, it’s virtually impossible to change these labyrinthian processes – despite those noble “continuous improvement” initiatives that are seemingly promoted 24X7.

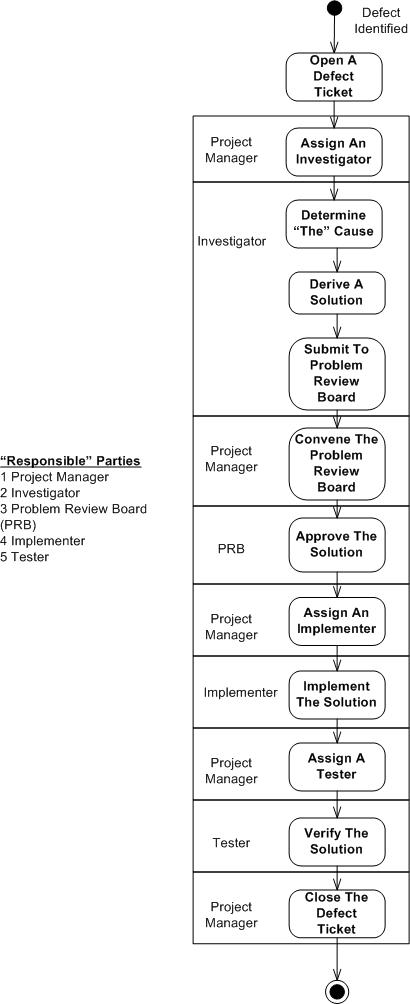

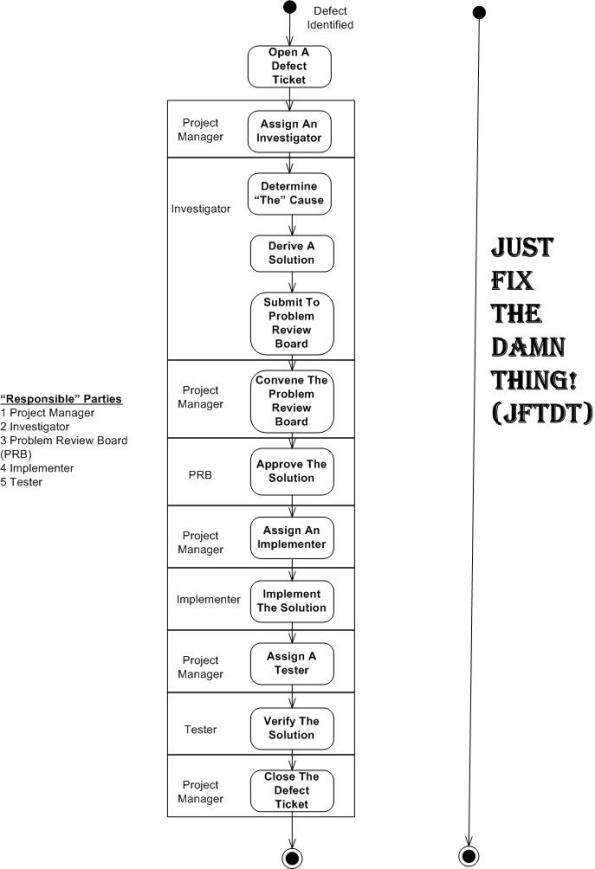

The state transition diagram below models a hypothetical schedule and budget busting maintenance process. But beware! Since BD00 likes to make sh*t up, the 5 role, 12 step, bureaucrat’s dream is a totally contorted fabrication that has no semblance to the truth.

Of course, some classes of discovered product defects should indeed be run through the ringer so that they don’t happen again. But mindlessly requiring every single defect (e.g. a low risk, one-line code change?, formatting violation?, documentation typo?) to plod through the glorious process is akin to using brain surgery to cure a headache.

Many of these process worshipping orgs can save a ton of time, money, and frustration if they “allowed” a parallel JFTDT process for those simple, low risk, defects discovered during and after a product is developed.

But no! In zombie orgs that have these types of beloved processes in place, it can’t be done. Despite the unsubstantiated and outrageous BD00 claim that the vast majority of discovered defects in most projects can be safely run through the insanely simple JFTDT process, anyone who’s not the CEO that thinks of advocating for a parallel, streamlined process should think twice. No one wants to be the next dude who gets shoved through the hidden JSTFU process.

Burn Baby Burn

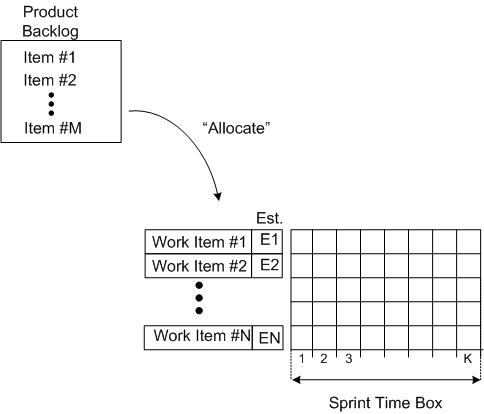

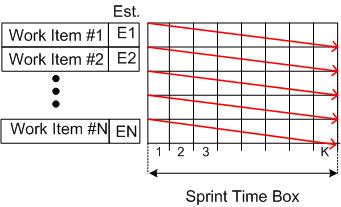

The “time-boxed sprint” is one of the star features of the Scrum product development process framework. During each sprint planning meeting, the team estimates how much work from the product backlog can be accomplished within a fixed amount of time, say, 2 or 4 weeks. The team then proceeds to do the work and subsequently demonstrate the results it has achieved at the end of the sprint.

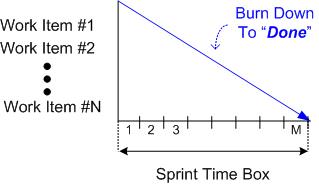

As a fine means of monitoring/controlling the work done while a sprint is in progress, some teams use an incarnation of a Burn Down Chart (BDC). The BDC records the backlog items on the ordinate axis, time on the abscissa axis, and progress within the chart area.

The figure below shows the state of a BDC just prior to commencing a sprint. A set of product backlog items have been somehow allocated to the sprint and the “time to complete” each work item has been estimated (Est. E1, E2….).

At the end of the sprint, all of the tasks should have magically burned down to zero and the BDC should look like this:

So, other than the shortened time frame, what’s the difference between an “agile” BDC and the hated, waterfall-esque, Gannt chart? Also, how is managing by burn down progress any different than the hated, traditional, Earned Value Management (EVM) system?

So, other than the shortened time frame, what’s the difference between an “agile” BDC and the hated, waterfall-esque, Gannt chart? Also, how is managing by burn down progress any different than the hated, traditional, Earned Value Management (EVM) system?

I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by – Douglas Adams

In practice, which of the outcomes below would you expect to see most, if not all, of the time? Why?

We need to estimate how many people we need, how much time, and how much money. Then we’ll know when we’re running late and we can, um, do something.