Archive

Accessing Configuration Data

Assume that on initialization, your C++ application reads in a bunch of configuration parameters from secondary storage prior to commencing its runtime mission. Via a trio of simple UML class diagrams, the figure below shows three ways (patterns?) to structure your application to read in and store configuration data for subsequent use by the program‘s productive, value added classes (user1, user2, etc).

In the first design, a singleton class is used to read and store the runtime configuration in RAM. The singleton can either be auto-instantiated at program load time in global/namespace memory before main() executes, or the first time it is accessed by one of the program’s user objects.

In the second approach, you employ a “ConfigOwner” class that encapsulates and owns the configuration data reader class (AppConfig). On program startup, the “ConfigOwner” object instantiates the “AppConfig” reader object and then subsequently passes a reference/pointer to it to all the user objects (which the “ConfigOwner” object doesn’t own).

In the third strategy, a higher level object (AppEncapsulator) owns all other objects in the application. On startup, this parent class is instantiated first. It fully controls the initialization sequence, creating the “AppConfig” object first and then pushing a reference/pointer to it down to its child User class objects when it subsequently constructs them.

Since the application startup sequence is centrally controlled, the third, parent-child approach is totally thread-safe. The implementation of the singleton approach, where the singleton is instantiated at program load time before main() starts executing, is also thread safe. The instantiation-on-first-access singleton approach and the ConfigOwner approach are subtlely thread unsafe without some clever synchronization coding added to ensure that the AppConfig object is fully constructed before it is accessed by its users.

Since I’m not fond of using singletons in situations where they’re not absolutely required (and this is arguably one of those cases, no?) and I disdain “clever” coding, I prefer the last, centrally controlled strategy. How about you? Are you clever, or a simpleton like me?

Note: Don’t mind the bracket turd on the right of the diagram. Since I’m a lazy ass and I try not to be a perfectionist when perfection is not needed, I left the pooper in rather than removing, fixing, and reinserting the graphic into the post. Too much work.

To Call, Or To Be Called. THAT Is The Question.

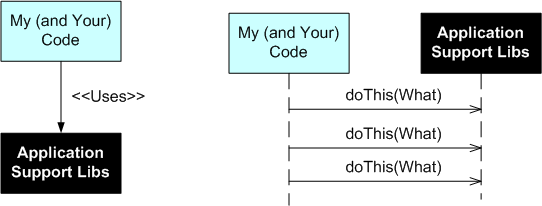

Except for GUIs, I prefer not to use frameworks for application software development. I simply don’t like to be the controllee. I like to be the controller; to be on top so to speak. I don’t like to be called; I’d rather call.

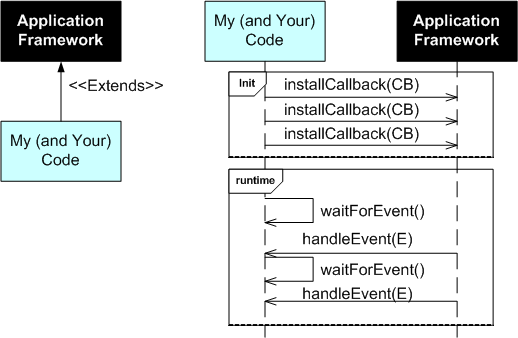

The UML figure below shows a simple class diagram and sequence diagram pair that illustrate how a typical framework and an application interact. On initialization, your code has to install a bunch of CallBack (CB) functions or objects into the framework. After initialization, your code then waits to be called by the framework with information on Events (E) that you’re interested in processing. You’re code is subservient to the Framework Gods.

After object oriented inheritance and programming by difference, frameworks were supposed to be the next silver bullet in software reuse. Well crafted, niche-based frameworks have their place of course, but they’re not the rage they once were in the 90s. A problem with frameworks, especially homegrown ones, is that in order to be all things to all people, they are often bloated beyond recognition and require steep learning curves. They also often place too much constraint on application developers while at the same time not providing necessary low level functionality that the application developer ends up having to write him/herself. Finding out what you can and can’t do under the “inverted control” structure of a framework is often an exercise in frustration. On the other hand, a framework imposes order and consistency across the set of applications written to conform to it’s operating rules; a boon to keeping maintenance costs down.

The alternative to a framework is a set of interrelated, but not too closely coupled, application domain libraries that the programmer (that’s you and me) can choose from. The UML class and sequence diagram pair below shows how application code interacts with a set of needed and wanted support libraries. Notice who’s on top.

How about you? Do you like to be on top? What has been your experience working with non-GUI application frameworks? How about system-wide frameworks like CORBA or J2EE?

How about you? Do you like to be on top? What has been your experience working with non-GUI application frameworks? How about system-wide frameworks like CORBA or J2EE?

Unconscious, Conscious, Bozo, Helper

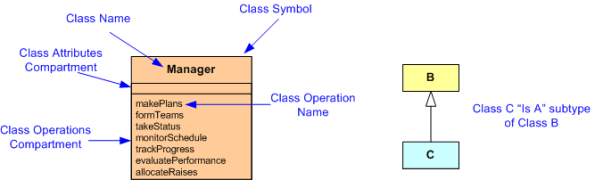

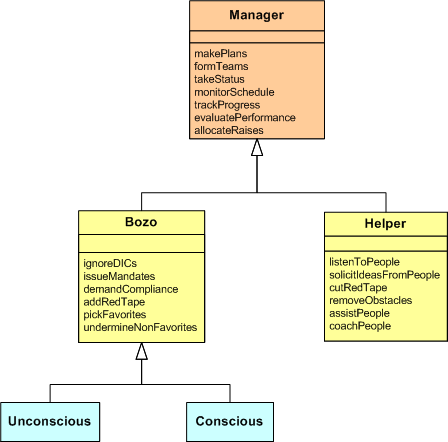

The following sparsely “bent” UML class diagram (see the end of this post for a quick and dorky tutorial for interpreting the diagram) exposes Bulldozer00’s internal hierarchy of manager types. Yours may be different, especially if you’re a manager.

The Base Class

The hierarchy’s Manager base class supplies all the mundane operations that sub-classed managers inherit and perform. For example, all managers in this particular inheritance tree make project plans, track project progress, and monitor progress against the plans. The frequency at which these behaviors are performed, along with the exact details of how they’re executed, is both manager-specific and project-specific. For example, during performance of the “takeStatus” operation, one manager may require project members to write out detailed weekly status reports whilst another may just require informal verbal status.

The Sub-Classes

The second level in Bulldozer00’s morbid and disturbing manager class hierarchy is more interesting. There are two polar opposite sub-types; Bozo and Helper. In addition to inheriting the boring, mechanical, and necessary responsibilities of the Manager base class, these subclasses provide radically different sets of behaviors. For instance, the Bozo subclass provides an “ignoreDICs” behavior whilst the Helper subclass provides “listenToPeople” and “solicitIdeas” behaviors. Comparing the behavior sets between the two subclasses and then against your own manager(s), how would you classify your manager(s)?

As the diagram shows, there are two Bozo Manager subtypes: Conscious and Unconscious. There’s no equivalent subdivision for the Helper Manager type because all Helper Manager “instantiations” are fully conscious. Hell, since all the behaviors that Helper Managers exhibit are so extraordinarily rare, productive, and against-the-grain, there is no way they can be unconscious and not know what they’re doing.

In Bulldozer00’s experience, most Bozo Managers are of the Unconscious ilk. They continuously execute the counterproductive behaviors forwarded on to them via their Bozo inheritance, but they don’t realize how detrimental their actions and words are to the orgs they’re responsible for growing and developing. Since virtually all their fellow clique members behave the same way, they’re oblivious to alternatives and they can’t connect poor org performance to their own dysfunctional behaviors.

Forgive them, for they know not what they do. – Jesus

Lastly, we come to the Conscious Bozo Manager class. Beware of these dudes, of which there are few (thank god), because they are hell on wheels. These guys/gals know fully well that their behaviors/actions are both locally and globally destructive. But why, you ask, would they behave this way? Well, because they’re out to inflate their heads and wallets and there are no boundaries they wouldn’t cross to achieve their goals.

Advice

If you choose to embrace, internalize, and use Bulldozer00’s class hierarchy to evaluate and “privately” judge your managers, you might want to take these suggestions into consideration:

- Run like hell from the Conscious Bozo types.

- Do your best to bring consciousness to the legions of well meaning, but sleepwalking, Unconscious Bozo types

- Attach yourself like a lamprey to the Helper type

But why the hell would you want to “buy into” Bulldozer00’s manager taxonomy? Great freakin’ question!

Appendix: Mini Class Diagram Graphic Tutorial

A Blessing And A Curse

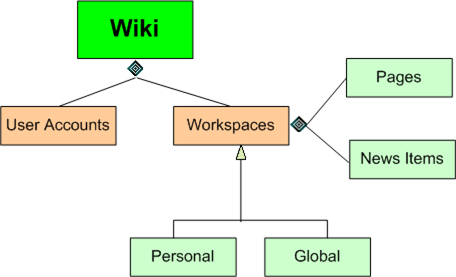

The figure below depicts a UML class diagram model of the static structure of a typical Wiki system. A Wiki may be comprised of many personally controlled and/or global workspaces. Each logical workspace is composed of user created work pages and news items (a.k.a. blog posts). Lastly, a Wiki contains many user accounts that are either created by the users themselves or, in a more controlled environment, created by a gatekeeper system administrator. Without an account, a user cannot contribute content to the Wiki database.

Org Wikis are both a blessing and a curse. They’re a blessing for the DICforce in that they allow for close collaboration and rapid, real-time information exchange between and across teams. They also serve as an easily searchable and publicly visible record of org history.

In malevolent and stovepiped CCHs where SCOLs and BOOGLs rarely communicate horizontally and, even more rarely, downward to the DICforce, Wikis are a curse because….

Networks make organizational culture and politics explicit. – Michael Schrage

BOOGLs and SCOLs that preside over malevolent CCHs don’t like having their day-to-day operational behavior exposed to the light of day. If a malevolent CCH org is liberal enough to “approve” of Wiki usage, chances are that none of the BOOGLs or SCOLs will contribute to its content. In the worse case, a Wiki police force may be established to enforce posting rules designed to keep politics and positioning behavior secret. Hell, without censorship, the DICforce might form the opinion that they are being led by a gang of thugs who are out for themselves instead of the lasting well being of the org.

Are you here to build a career or to build an organization? – Peter Block

BS Design

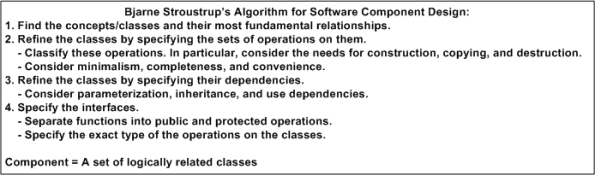

Sorry, but I couldn’t resist naming the title of this post as it is written. However, despite what you may have thought on first glance, BS stands for dee man, Bjarne Stroustrup. In chapter 23 of “The C++ Programming Language“, Bjarne offers up this advice regarding the art of mid-level design:

To find out the details of executing each iterative step in the while(not_done){} loop, go buy the book. If C++ is your primary programming language and you don’t have the freakin’ book, then shame on you.

Bjarne makes a really good point when he states that his unit of composition is a “component”. He defines a component as a cluster of classes that are cohesively and logically related in some way.

A class should ideally map directly into a problem domain concept, and concepts (like people) rarely exist in isolation. Unless it’s a really low level concrete concept on the order of a built in type like “int”, a class will be an integral player in a mini system of dynamically collaborating concepts. Thinking myopically while designing and writing classes (in any language that directly supports object oriented design) can lead to big, piggy classes and unnecessary dependencies when other classes are conceived and added to the kludge under construction – sort of like managers designing an org to serve themselves instead of the greater community. 🙂

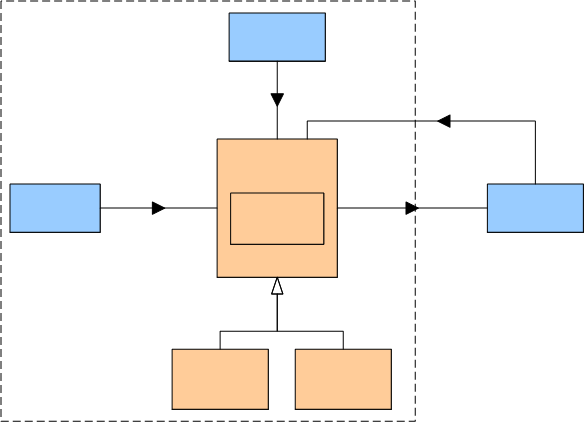

The figure below shows “revision 0” of a mini system of abstract classes that I’m designing and writing on my current project. The names of the classes have been elided so that I don’t get fired for publicly disclosing company secrets. I’ve been architecting and designing software like this from the time I finally made the painful but worthwhile switchover to C++ from C.

The class diagram is the result of “unconsciously” applying step one of Bjarne’s component design process. When I read Bjarne’s sage advice it immediately struck a chord within me because I’ve been operating this way for years without having been privy to his wisdom. That’s why I wrote this blowst – to share my joy at discovering that I may actually be doing something right for a change.

Hold The Details, Please

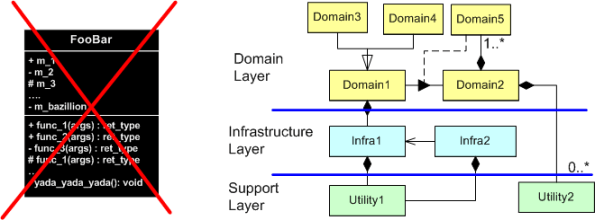

When documenting software designs (in UML, of course) before, during, or after writing code, I don’t like to put too much detail in my models. By details, I mean exposing all public/protected/private data members and functions and all intra-member processing sequences within each class. I don’t like doing it for these reasons:

- I don’t want to get stuck in a time-busting, endless analysis paralysis loop.

- I don’t want a reviewer or reader to lose the essence of the design in a sea of unnecessary details that obscure the meaning and usefulness of the model.

- I don’t want every little code change to require a model change – manual or automated.

I direct my attention to the higher levels of abstraction, focusing on the layered structure of the whole. By “layered structure”, I mean the creation and identification of all the domain level classes and the next lower level, cross-cutting infrastructure and utility classes. More importantly, I zero in on all the relationships between the domain and infrastructure classes because the real power of a system, any system, emerges from the dynamic interactions between its constituent parts. Agonizing over the details within each class and neglecting the inter-class relationships for a non-trivial software system can lead to huge, incoherent, woeful classes and an unmaintainable downstream mess. D’oh!

How about you? What personal guidelines do you try to stick to when modeling your software designs? What, you don’t “do documentation“? If you’re looking to move up the value chain and become more worthy to your employer and (more importantly) to yourself, I recommend that you continuously learn how to become a better, “light” documenter of your creations. But hey, don’t believe a word I say because I don’t have any authority-approved credentials/titles and I like to make things up.

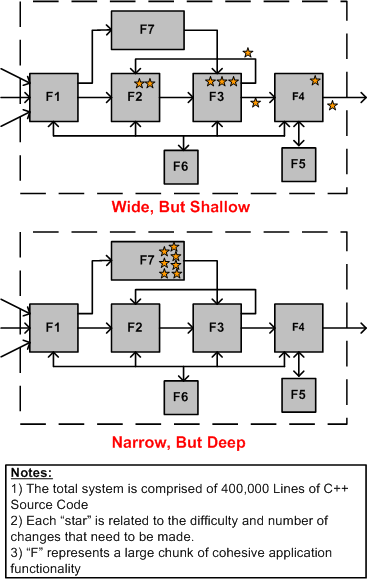

Wide But Shallow, Narrow But Deep

I just “finished” (yeah,that’s right –> 100% done (LOL!)) exploring, discovering, defining, and specifying, the functional changes required to add a new feature to one of our pre-existing, software-intensive products. I’m currently deep in the trenches exploring and discovering how to specify a new set of changes required to add a second related feature to the same product. Unlike glamorous “Greenfield” projects where one can start with a blank sheet of paper, I’m constrained and shackled by having to wrestle with a large and poorly documented legacy system. Sound familiar?

The extreme contrast between the demands of the two project types is illuminating. The first one required a “wide but shallow” (WBS) analysis and synthesis effort while the current one requires a “narrow but deep” (NBD) effort. Both types of projects require long periods of sustained immersion in the problem domain, so most (all?) managers won’t understand this post. They’re too busy running around in ADHD mode acting important, goin’ to endless agenda-less meetings, and puttin’ out fires (that they ignited in the first place via their own neglect, ignorance, and lack of listening skills). Gawd, I’m such a self-righteous and bad person obsessed with trashing the guild of management 🙂 .

The figure below highlights the difference between WBS and NBD efforts for a “hypothetical” product enhancement project.

In WBS projects, the main challenge is hunting down all the well hidden spots that need to be changed within the behemoth. Missing any one of these change-spots can (and usually does) eat up lots of time and money down the road when the thing doesn’t work and the product team has to find out why. In NBD projects, the main obstacle to overcome is the acquisition of the specialized application domain knowledge and expertise required to perform localized surgery on the beast. Since the “search” for the change/insertion spots of an NBD effort is bounded and localized, an NBD effort is much lower risk and less frustrating than a WBS effort. This is doubly true for an undocumented system where studying massive quantities of source code is the only way to discover the change points throughout a large system. It’s also more difficult to guesstimate “time to completion” for a WBS project than it is for an NBD project. On the other hand, much more learning takes place in a WBS project because of the breadth of exposure to large swaths of the code base.

Assuming that you’re given a choice (I know that this assumption is a sh*tty one), which type of project would you choose to work on for your next assignment; a WBS project, or an NBD project? No cheatin’ is allowed by choosing “neither” 😉 .

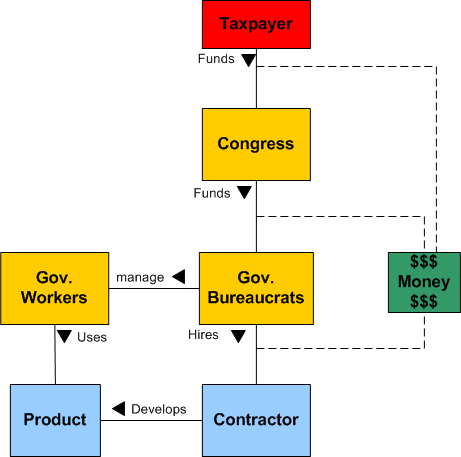

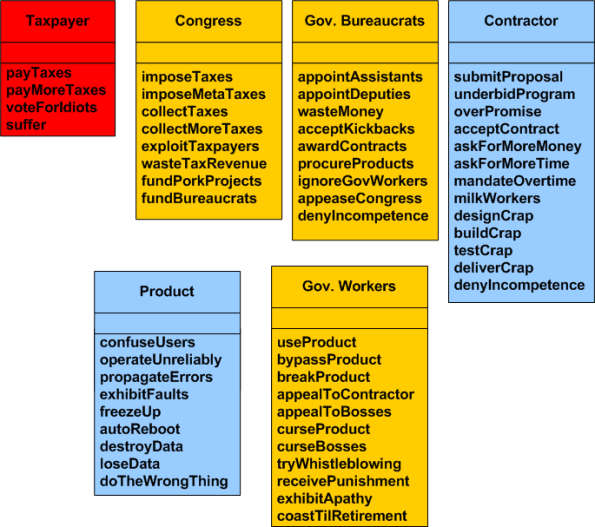

Government Business

The figure below is a UML (Unified Modeling Language) class diagram that models a fictional government contracting system. So you don’t know UML? Don’t leave, because UML is easy to understand if one doesn’t over-specify in an attempt to show the world how “smart” he/she is.

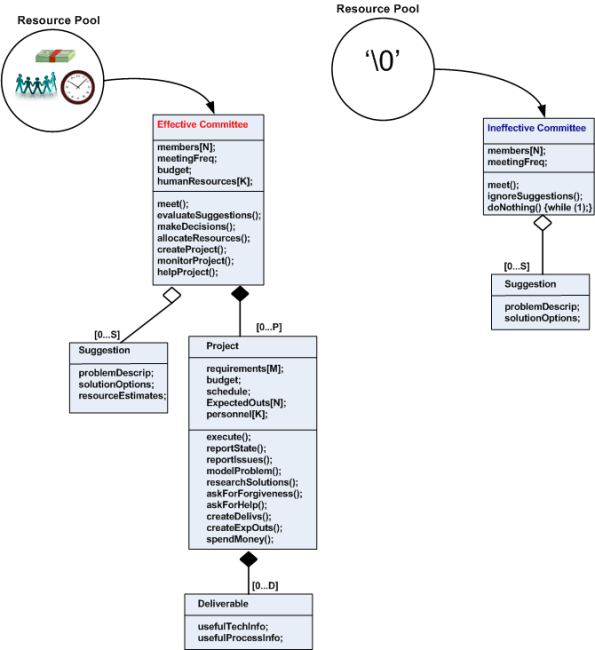

The diagram shows the players (“classes” in UML lingo) in the game and some of the relationships (“associations” in UML lingo) between them. The diagram can be understood as follows:

The taxpayer funds congress, which funds groups of government bureaucrats, who hire a contractor to develop and deliver a product to be used by government workers to do their job of serving the public. Money, which everyone worships of course, ties all these main power players together. The contractor develops a product, which is then (delivered to the government and is) used by the government workers. All is well and the world becomes a better place. Whoopeee!

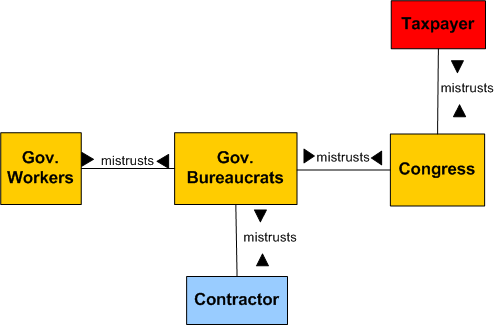

Yawn, meh. Boring and uninteresting, no? But wait, there’s more. Some hidden relationships between the “classes” in the system are not displayed by this proper and politically correct diagram. The diagram below shows just one of these hidden relationships – mistrust – between everyone 🙂 . How did this mistrust emerge and infiltrate the system? From the players getting burned in the past, that’s how. Especially the ultimate source of all money in the system – the taxpayer.

The last figure in this post shows the dynamic behaviors exhibited by each of the active players in this goverment business dance. In the UML, the middle compartment in a “class” (which is nothing more than a type of object – a classification) is intended to hold the attributes that characterize the class. I purposefully left them out because they’re not important to the message I’m trying to communicate.

I’ll leave it to your imagination to create specific scenarios of system operation (called “use cases” in the UML). Scenarios are specific subsets of behaviors that are sequentially strung together in time (scenarios can be modeled with UML “sequence diagrams”). At the end of a given scenario execution, the system has achieved a specific goal, like “make everyone in the system miserable”, or “damage the environment”, or “reward those who deserve it the least and punish those who are innocent of wrongdoing”.

Are there any significant players missing in this system? Are there any relationships missing? Are there any behaviors missing? Got a different model of how this government system works or how it should work? Remember this:

The purpose of a system is what it does, not what its advocates say it does.

Thanks for listening!

Committees

The figure below depicts a “bent” UML class diagram of two types of committees. For those who don’t know UML, I hope that the diagram is sort of self-explanatory.