One Word

I’ve been waiting patiently (freakin’ impatiently?) for 10+ years for some word, any word, to dethrone “agile” as the most frequently seen word on book, video, and article titles in the software industry. Thanks to the highly esteemed Gartner consulting firm, perhaps we have a viable candidate:

“Bimodal IT refers to having two modes of IT, each designed to develop and deliver information- and technology-intensive services in its own way. Mode 1 is traditional, emphasizing scalability, efficiency, safety and accuracy. Mode 2 is non-sequential, emphasizing agility and speed.” – Gartner IT Glossary

Personally, I like the word “Tradagile” better than “Bimodal“. It’s lighter, less stuffy.

I’m goin’ Bimodal! W00t!

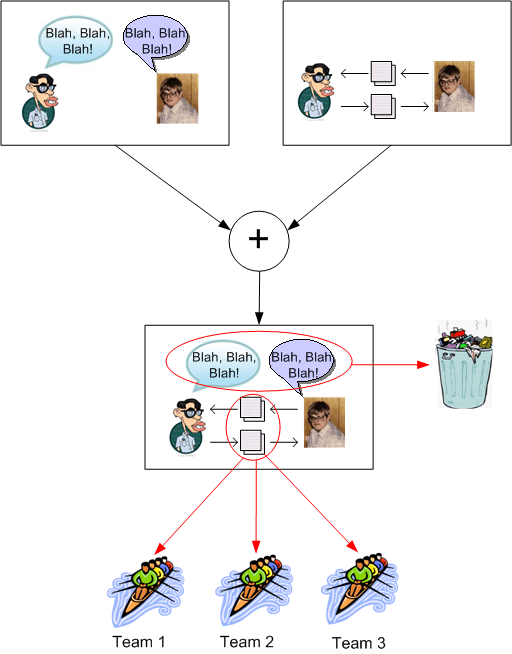

More Effective Than, But Not As Scalable As

If you feel you have something to offer the world, the best way to expose and share your ideas/experiences/opinions/knowledge/wisdom is to release it from lock down in your mind and do the work necessary to get it into physical form. Write it down, or draw it up, or record it. Then propagate it out into the wild blue yonder through the greatest global communication system yet known to mankind: the internet.

You are not personally scalable, but because of the power of the internet, the artifacts you create are. Fuggedabout whether anybody will pay attention to what you create, manifest, and share. Birth it and give it the possibility to grow and prosper. Perhaps no one’s eyeballs or ears other than yours will ever come face to face with your creations, but your children will be patiently waiting for any and all adopters that happen to come along.

The agilista community is fond of trashing the “traditional” artifact-exchange method of communication and extolling the virtues of the effectiveness of close proximity, face-to-face, verbal exchange. Alistair Cockburn even has some study-backed curves that bolster the claim. BD00 fully agrees with the “effectiveness” argument, but just like the source code is not the whole truth, face-to-face communication is not the whole story. As noted in the previous paragraph, a personal conversation is not scalable.

Face to face, verbal communication may be more effective than artifact exchange, but it’s ephemeral, not archive-able, and not nearly as scalable. And no half-assed scribblings on napkins, envelopes, toilet paper, nor index cards solve those shortcomings on anything but trivial technical problems.

Join The Club

My good Twitter buddy (and perhaps future book co-author), Mr. Jon Quigley, pointed me toward this great picture:

Well… that’s not exactly the original picture. I took the liberty to paste Bulldozer00’s puss over the machine operator’s face. It simply felt like the right thing to do.

That picture is much more apropos than you think. When I golf, I seem to always hit my balls into debunker!

Both Inane And Insane

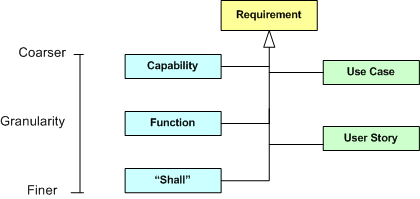

Let’s start this post off by setting some context. What I’m about to spout concerns the development of large, complex, software systems – not mobile apps or personal web sites. So, let’s rock!

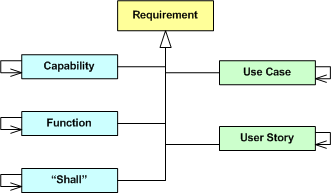

The UML class diagram below depicts a taxonomy of methods for representing and communicating system requirements.

On the left side of the diagram, we have the traditional methods: expressing requirements as system capabilities/functions/”shalls”. On the right side of the diagram, we have the relatively newer artifacts: use cases and user stories.

When recording requirements for a system you’re going to attempt to build, you can choose a combination of methods as you (or your process police) see fit. In the agile world, the preferred method (as evidenced by 100% of the literature) is to exclusively employ fine-grained user stories – classifying all the other, more abstract, overarching, methods as YAGNI or BRUF.

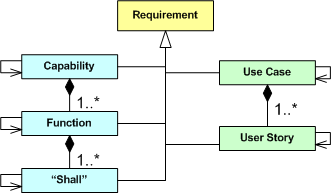

As the following enhanced diagram shows, whichever method you choose to predominantly start recording and communicating requirements to yourself and others, at least some of the artifacts will be inter-coupled. For example, if you choose to start specifying your system as a set of logically cohesive capabilities, then those capabilities will be coupled to some extent – regardless of whether you consciously try to discover and expose those dependencies or not. After all, an operational system is a collection of interacting parts – not a bag of independent parts.

Let’s further enhance our class diagram to progressively connect the levels of granularity as follows:

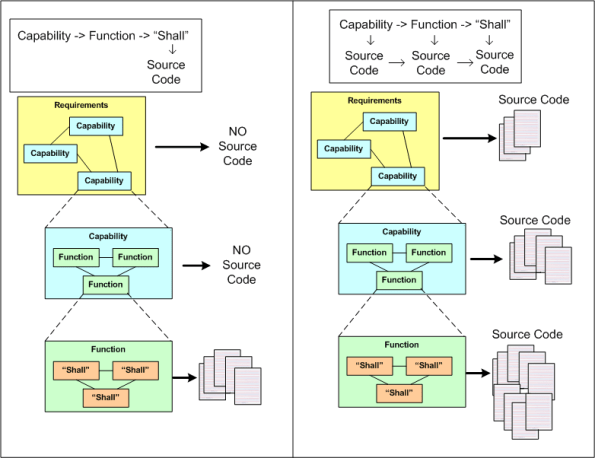

If you start specifying your system as a set of coarse-grained, interacting capabilities, it may be difficult to translate those capabilities directly into code components, packages, and/or classes. Thus, you may want to close the requirements-to-code intellectual gap by thoughtfully decomposing each capability into a set of logically cohesive, but loosely coupled, functions. If that doesn’t bridge the gap to your liking, then you may choose to decompose each function further into a finer set of logically cohesive, but loosely coupled, “shall” statements. The tradeoff is time upfront for time out back:

- Capabilities -> Source Code

- Use Cases – > Source Code

- Capabilities -> Functions -> Source Code

- Use Case -> User Story -> Source Code

- Capabilities -> Functions -> “Shalls” -> Source Code

Note that, taken literally, the last bullet implies that you don’t start writing ANY code until you’ve completed the full, two step, capabilities-to-“shalls” decomposition. Well, that’s a croc o’ crap. You can, and should, start writing code as soon as you understand a capability and/or function well enough so that you can confidently cut at least some skeletal code. Any process that prohibits writing a single line of code until all the i’s are dotted and all the t’s are crossed and five “approval” signatures are secured is, as everyone (not just the agile community) knows, both inane and insane.

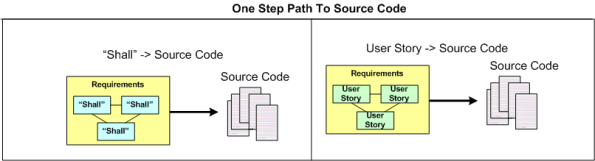

Of course, simple projects don’t need no stinkin’ multi-step progression toward source code. They can bypass the Capability, Function, and Use Case levels of abstraction entirely and employ only fine grained “shalls” or User Stories as the method of specification.

On the simplest of projects, you can even go directly from thoughts in your head to code:

The purpose of this post is to assert that there is no one and only “right” path in moving from requirements to code. The “heaviness” of the path you decide to take should match the size, criticality, and complexity of the system you’ll be building. The more the mismatch, the more the waste of time and effort.

Metal, Not Paper

Ooh, ooh! BD00 just whispered an idea into my wax-filled ear. The nasty creature said: “Instead of a dull piece of paper, agile certification bodies should present their graduates with a shiny new medal. They can jack up the course fee to cover the price difference.”

Brilliant! Graduates would be able to strut around the open air office wearing their hard won bling on their chests. A gaggle of medals on the chest would nicely complement a $20K gold iWatch on the wrist and separate the winners from the losers.

But alas, never listen to what BD00, and I, as his sanctioned branding consultant, have to say. Never forget that….

Milk Those Suckers!

Lovers gonna love, haters gonna hate…

Want some more agile adoption lunacy? Then check out this post: The Five Secrets.

Abstracting Away Some Details

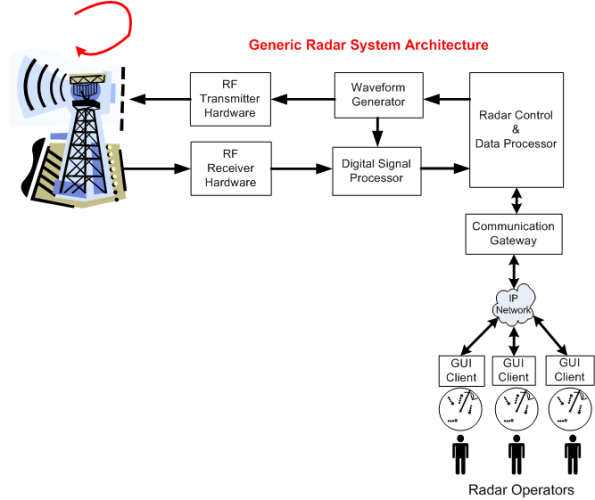

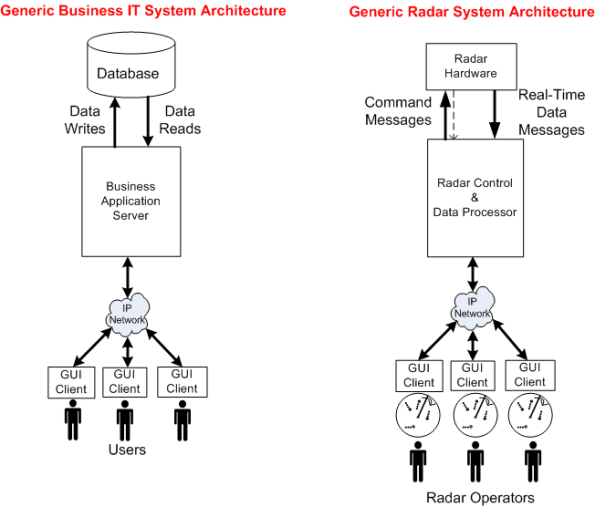

The following figure shows the general system architecture of a rotating, ground-based, radar whose mission is to detect and track “air breathing” targets. The chain of specially designed hardware and software subsystems provides radar operators with a 360 degree, real-time, surveillance picture of all the targets that fall within the physical range and elevation coverage capabilities of the Antenna and Transmit/Receive subsystems.

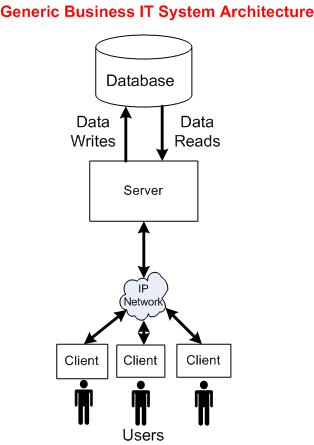

The following picture shows the general architecture of a business IT system. Unlike the specialized radar system architecture, this generic IT structure supports a wide range of application domains: insurance, banking, e-commerce, social media, etc.

To explore the technical similarities/differences between the two platforms, let’s abstract away the details of everything to the left of the Radar Control & Data Processor and stuff them into a box called “Radar Hardware“. We’ll also tuck away the radar’s Communication Gateway functionality by placing it inside the Radar Control & Data Processor:

Now that we’ve used the power of abstraction to wrestle the original radar system architecture into a form similar to a business IT system, we can reason about some of the differences between the two structures.

Actually, I’m gonna stop here and leave the analysis of the technical similarities and differences as a thought experiment to you, dear reader. That’s because this is one of those posts that took me for freakin’ ever to write. I must have iterated over the draft at least 20 times during the past month. And of course, I had no master plan when I started writing it, so I hope you at least enjoy the pretty pictures.

Convergence To Zero

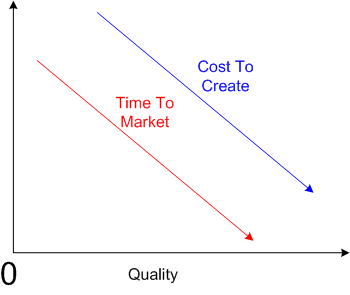

Maybe it’s just me, but I think that some people, especially managers and executives, auto-equate decreasing “cost to create” (CTC) and decreasing “time to market” (TTM) with increasing “quality“. Actually, since they’re always yapping about CTC and TTM, but rarely about about quality, perhaps they think there is no correlation between CTC/TTM and quality.

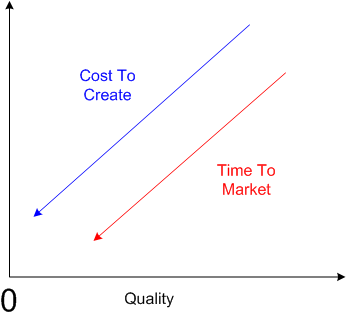

But consider the polar opposite, where decreasing the CTC and decreasing the TTM decreases quality.

I think both of the above cases are extreme generalities, but unless I’m missing something big, I do know one thing. In the limit, if you decrease the CTC and TTM to zero, you won’t produce anything; nada. Hence, quality converges to zero – even though the first graph in this post gives the illusion that it doesn’t.

Currently, in the real world, the iron triangle still rules:

Currently, in the real world, the iron triangle still rules:

Time, Cost, Quality: Pick any two at the expense of the third.

Note: If you’re a hip, new age person who likes to substitute the vague word “value” for the just-as-vague word “quality”, then by all means do so.

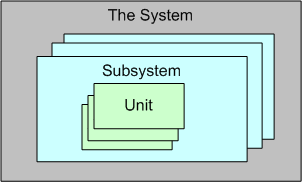

Convex, Not Linear

For a large, complex software system that can be represented via an instantiation of the above template, three levels of testing are required to be performed prior to fielding a system: unit, integration, and system. Unit testing shakes out some (hopefully most) of the defects in the local, concretely visible, micro-behavior, of each of possibly thousands of units. Integration testing unearths the emergent behaviors, both intended and unintended, of each individual subsystem assembly. System level, end-to-end, testing is designed to do the same for the intended/unintended behaviors of the whole shebang.

Now that the context has been set for this post, let’s put our myopic glasses on and zero in on the activity of unit testing. Unit testing is unarguably a “best practice“. However, just because it’s a best practice, does it mean we should, as one famous software character has hinted, strive to “turn the dials up to 10” on unit testing (or any other best practice?).

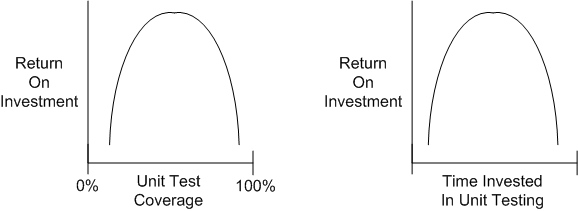

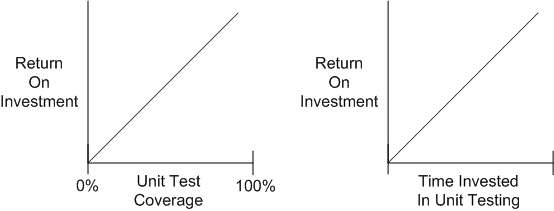

Check out these utterly subjective, unbacked-by-data, convex, ROI graphs:

If you believe these graphs hold true, then you would think that at some point during unit testing, you’d get more bang for the buck by investing your time in some other value-added task – such as writing another software unit or defining and running “higher level” integration and/or system tests on your existing bag of units.

Now, check out these utterly subjective, unbacked-by-data, linear, “turn the dials up to 10“, ROI graphs:

People who have drank the whole pitcher of unit-testing koolaid tend to believe that the linear model holds true. These miss-the-forest-for-the-trees people have no qualms about requiring their developers to achieve arbitrarily high unit test coverage percentages (80%, 85%, 90%, 100%) whilst simultaneously espousing the conflicting need to reduce cost and delivery time.

Given a fixed amount of time for unit + integration + system testing in a finite resource environment, how should that time be allocated amongst the three levels of testing? I don’t have any definitive answer, but when schedules get tight, as so often happens in the real world, something has gotta give. If you believe the convex unit testing model, then lowering unit test coverage mandates should be higher on your list of potential sacrificial lambs than cutting integration or system test time – where the emergent intended, and more importantly, unintended, behaviors are made visible.

Like Big Requirements Up Front (BRUF) and its dear sibling, Big Design Up Front (BDUF), perhaps we should add “Big Unit Testing Tragedy” (BUTT) to our bag of dysfunctional practices. But hell, it won’t be done. The linear thinkers seem to be in charge.

Note: Jim Coplien has been eloquently articulating the wastefulness of too much unit testing for years. This post is simply a similar take on his position: