Archive

A Blast From The Past

One of the first from-scratch products I ever worked on was named “BEXR” (Beacon Extractor & Recorder, pronounced “Beck’s-uhr“). I proposed the name BEVR (Beacon Evaluation & Video Recorder, pronounced “beaver“), but it was shot down by the marketing department immediately for who knows why 🙂

BEXR was a custom hardware and software combo that connected to the raw, low-level, return signals received by FAA secondary surveillance radars from aircraft-based transponders. The product allowed FAA maintenance personnel to observe and evaluate the quality of radar and transponder signals in real-time – much like a specialized oscilloscope. In addition, it supported recording and playback capabilities for off-site analysis.

Despite it’s utility to the FAA, BEXR was politically controversial. Since non-conforming aircraft transponders were relatively expensive to fix and reinstall, owners of small aircraft did not like being “spied upon“. They did not want to know if their equipment was out-of-spec. Thus, BEXR’s mission was limited to troubleshooting only radar issues.

BEXR was comprised of two, custom-designed, 16 bit, PC-AT bus cards. They were packaged in a portable PC that was carted to/from the radar site under investigation. I was the BEXR product manager and the GUI developer. I wrote the GUI Operator Control Software (OCS) in C using Microsoft’s Quick C IDE. The software directly used the Windows 3.1 C APIs to display application-specific windows, dialog boxes, target positions, and control buttons/lists. Compared to today’s GUI tools/API’s, it was the equivalent of writing assembler code for GUIs, but I had a lot of fun writing it. 🙂

The reason I decided to write this post is because I recently ran across a pack of sticky cards that we used to market the product and hand out at trade shows. It was a blast from the past….

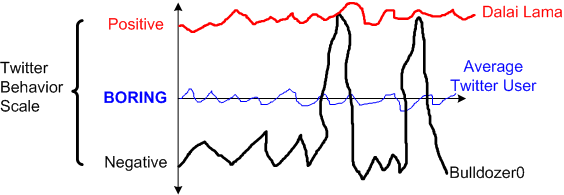

The TBS

What I’m Working On

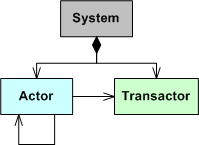

Here’s a structured decomposition of some of the program’s stakeholders.

Now, all I gotta do is find out who the “product owner” is and invite him/her to our daily Scrum standup meetings. Better yet, I’m gonna hire an “agile scaling” expert to parachute in and guide the team to on-time, under-budget success.

As you can see from the following slide, the program is docu-centric. Not one, but three upfront plans? WTF! No problemo. I’ll just sit all the stakeholders down and convince them all that “traditional” documentation stuff is unimportant and so-yesterday.

To hell with any upfront requirements and design thinking and capturing, we’ll start TDDing our way forward, discovering what needs to be done as we go. From day 1, we’ll start delivering software in monthly increments for the entire 3 year duration of the program. We’ll simply mock out all the mechanical, microwave, and digital signal processing hardware so we can go faster than a speeding bullet – twice the work in half the time. Trust us, it’ll all work out – we’re agile.

Note: You can get the full deck of slides from FedBizOps.com.

Note: You can get the full deck of slides from FedBizOps.com.

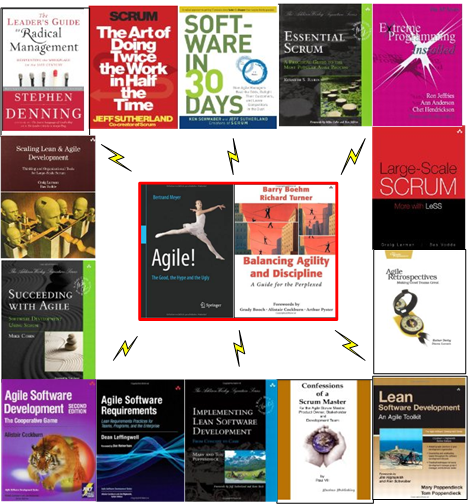

Battling The Confirmation Bias

On my first pass through Bertrand Meyer’s “Agile!” book, I interpreted its contents as a well-reasoned diatribe against agilism (yes, “agile” has become so big that it warrants being called an “ism” now). Because I was eager to do so, I ignored virtually all the positive points Mr. Meyer made and fully embraced his negative points. My initial reading was a classic case of the “confirmation bias“; where one absorbs all the evidence aligning with one’s existing beliefs and jettisons any evidence to the contrary. I knew that the confirmation bias would kick in before I started reading the book – and I looked forward to scratching that ego-inflating itch.

On my second pass through the book, I purposely skimmed over the negatives and concentrated on the positives. Here is Mr. Meyer’s list of positive ideas and practices that “agile” has either contributed to, or (mostly) re-prioritized for, the software development industry:

- The central role of production code over all else

- Tests and regression test suites as first class citizens

- Short, time-boxed iterations

- Daily standup meetings

- The importance of accommodating change

- Continuous integration

- Velocity tracking & task boards

I should probably end this post here and thank the agile movement for refocusing the software development industry on what’s really important… but I won’t 🙂

The best and edgiest writing in the book, which crisply separates it from its toned down (but still very good) peer, Boehm and Turner’s “Balancing Agility And Discipline“, is the way Mr. Meyer gives the agilencia a dose of its own medicine. Much like some of the brightest agile luminaries (e.g. Sutherland, Cohn, Beck, Jeffries, Larman, Cockburn, Poppendieck, Derby, Denning (sic)) relish villainizing any and all traditional technical and management practices in use before the rise of agilism, Mr. Meyer convincingly points out the considerable downsides of some of agile’s most cherished ideas:

- User stories as the sole means of capturing requirements (too fine grained; miss the forest for the trees)

- Pair programming and open offices (ignores individual preferences, needs, personalities)

- Rejection of all upfront requirements and design activities (for complex systems, can lead to brittle, inextensible, dead-end products)

- Feature-based development and ignorance of (inter-feature) dependencies (see previous bullet)

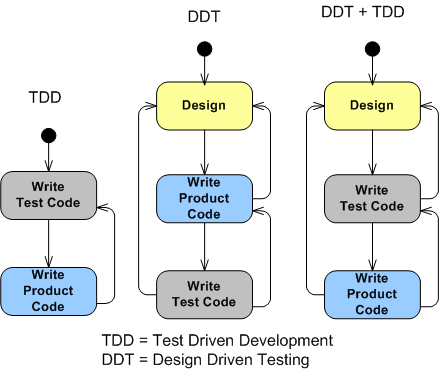

- Test Driven Development (myopic, sequential test-by-test focus can lead to painting oneself into a corner).

- Coach as a separate role (A ploy to accommodate the burgeoning agile consulting industry. Need more doer roles, not talkers.)

- Embedded customer (There is no one, single, customer voice on non-trivial projects. It’s impractical and naive to think there is one.)

- Deprecation of documents (no structured repository of shared understanding to go to seek clarification on system level requirements/architecture/design issues; high maintenance costs for long-lived systems; costly on-boarding of new developers)

I’ve always maintained that there is much to like about the various agile approaches, but the way the agile big-wigs have been morphing the movement into a binary “do-this/don’t-do-that” religious dogma, and trashing anything not considered “agile“, is a huge turnoff to me. How about you?

Beware Of Micro-Fragmentation

While watching Neal Ford’s terrific “Agile Engineering Practices” video series, I paid close attention to the segment in which he interactively demonstrated the technique of Test Driven Development (TDD). At the end of his well-orchestrated example, which was to design/write/test code that determines whether an integer is a perfect number, Mr. Ford presented the following side-by-side summary comparison of the resulting “traditional” Code Before Test (CBT) and “agile” TDD designs.

As expected from any good agilista soldier, Mr. Ford extolled the virtues of the TDD derived design on the right without mentioning any downside whatsoever. However, right off the bat, I judged (and still do) that the compact, cohesive, code-all-in-close-proximity CBT design on the left is more readable, understandable, and maintainable than the micro-fragmented TDD design on the right. If the atomic code in the CBT isPerfect() method on the left ended up spanning much more space than shown, I may have ended up agreeing with Neal’s final assessment that the TDD result is better – in this specific case. But I (and hopefully you) don’t subscribe to this, typical-of-agile-zealots, 100% true, assertion:

The downside of TDD (to which there are, amazingly, none according to those who dwell in the TDD cathedral), is eloquently put by Jim Coplien in his classic “Why Most Unit Testing Is Waste” paper:

If you find your testers (or yourself) splitting up functions to support the testing process, you’re destroying your system architecture and code comprehension along with it. Test at a coarser level of granularity. – Jim Coplien

As best I can, I try to avoid being an absolutist. Thus, if you think the TDD generated code structure on the right is “better” than the integrated code on the left, then kudos to you, my friend. The only point I’m trying to make, especially to younger and less experienced software engineers, is this: every decision is a tradeoff. When it comes to your intimate, personal, work habits, don’t blindly accept what any expert says at face value – especially “agile” experts.

Tradagile

Even though hard-core agilistas (since every cause requires an evil enemy) present it as thus:

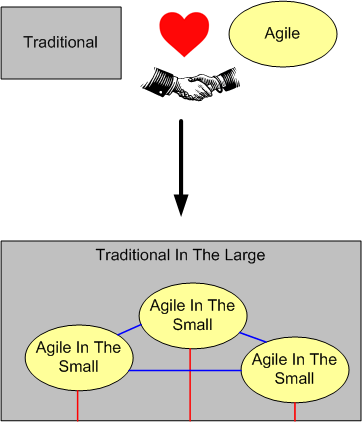

For large, complex, multi-disciplined, product developments, it should be as thus:

Scaling Up And Out

Ever since I discovered the venerable Erlang programming language and the great cast of characters (especially Joe Armstrong) behind its creation, I’ve been chomping at the bit to use it on a real, rent-paying, project. That hasn’t happened, but the next best thing has. I’m currently in the beginning stage of a project that will be using “Akka” to implement a web-based radar system gateway.

Akka is an Erlang-inspired toolkit and runtime system for the JVM that elegantly supports the design and development of highly concurrent and distributed applications. It’s written in Scala, but it has both Scala and Java language bindings.

Jonas Boner, the creator of Akka, was blown away by the beauty of Erlang and its ability to support “nine nines” of availability – as realized in a commercial Ericsson telecom product. At first, he tried to get clients and customers to start using Erlang. But because Erlang has alien, Prologue-based syntax, and its own special VM/development infrastructure, it was a tough sell. Thus, he became determined to bring”Erlangness” to the JVM to lower the barriers to entry. Jonas seems to be succeeding in his crusade.

At the simplest level of description, an Akka-based application is comprised of actors running under the control of an overarching Akka runtime system container. An actor is an autonomous, reactive entity that contains state, behavior, and an input mailbox from which it consumes asynchronously arriving messages. An actor communicates with its parents/siblings by issuing immutable, fire-and-forget (or asynchronous request-and-remember), messages to them. The only way to get inside the “head” of an actor is to send messages to it. There are no backdoors that allow other actors to muck with the inner state of an actor during runtime. Like people, actors can be influenced, but not explicitly coerced or corrupted, by others. However, also like people, actors can be terminated for errant behavior by their supervisors. 🙂

For applications that absolutely require some sort of shared state between actors, Akka provides transactors (and agents). A transactor is an implementation of software transactional memory that serializes access to shared memory without the programmer having to deal with tedious, error-prone, mutexes and locks. In essence, the Akka runtime unshackles programmers from manually handling the frustrating minutiae (deadlocks, race conditions (Heisenbugs), memory corruption, scalability bottlenecks, resource contention) associated with concurrent programming. Akka allows programmers to work at a much more pleasant, higher level of abstraction than the traditional, bare bones, threads/locks model. You spend more time solving domain-level problems than battling with the language/library implementation constraints.

You design an Akka based system by, dare I say, exercising some upfront design brain muscle:

- decomposing and allocating application functionality to actors,

- allocating data to inter-actor messages and transactors,

- wiring the actors together to structure your concurrent system as a network of cooperating automatons.

The Akka runtime supervises the application by operating unobtrusively in the background:

- mapping actors to OS threads and hardware cores,

- activating an actor for each message that appears in its mailbox,

- handling actor failures,

- realizing the message passing mechanisms.

Gee, I wonder if the agile TDD and the “no upfront anything” practices mix well with concurrent, distributed system design. Silly me. Of course they do. Like all things agile, they’re universally applicable in all contexts. (Damn, I thought I’d make it through this whole post without dissing the dogmatic agile priesthood, but I failed yet again.)

Akka not only makes it easy to scale up on a multi-core processor, Akka makes it simple to scale out and distribute (if needed) your concurrent design amongst multiple computing nodes via a URL-based addressing scheme.

There is much more deliciousness to Akka than I can gush about in this post (most notably, actor supervision trees, futures, routers, message dispatchers, etc), but you can dive deeper into Akka (or Erlang) if I’ve raised the hairs on the back of your geeky little neck. The online Akka API documentation is superb. I also have access to the following three Akka books via my safaribooksonline account:

Since C++ is my favorite programming language, I pray that the ISO C++ committee adds Erlang-Akka like abstractions and libraries to the standard soon. I know that proposals for software transactional memory and improved support for asynchronous tasking and futures are being worked on as we speak, but I don’t know if they’ll be polished enough to add to the 2017 standard. Hurry up guys :).

Blind Copy

I just finished watching Simon Brown’s brilliant talk: “Software Architecture vs Code”.

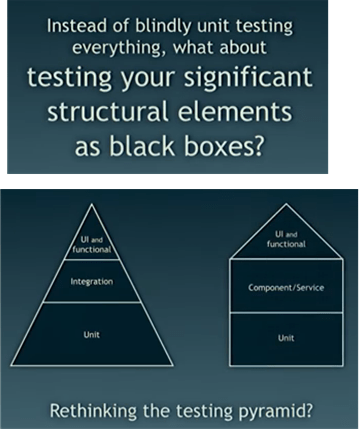

I thought the segment he presented on levels of testing was really, really good. Simon had the nerve to question the dogma of TDD and the dubious value of unit testing the hell out of your code (90%, 100% coverage anyone?). He cited the controversial writings of Jim Coplien and David Heinemeier-Hansson that poke some holes in those revered, extreme practices:

Like Cope and DHH, Simon does not advise shit-canning ALL unit testing. He simply suggests rethinking the test pyramid and how one allocates resources to the various levels of testing:

Instead of mandating 90 or 100 percent unit test coverage in order to create a high level of (false) confidence in your code base, perhaps you and your org should consider the potential silliness of the current obsession with TDD and writing huge unit test suites. Maybe you’d save some money and deliver your product faster. But then again, maybe not.

The Supreme Scrum Master

Even though I mildly resisted the urge to do so, I capitulated and posted this doubly disrespectful blasphemy:

Awe, come on. Drop the who-pooped-in-my-soup face, relax your sphincter, smile for an instant, and simply go with it. If the hermit kingdom’s supreme leader invested a little money ($2k) and time (3 fun-filled days) to add the coveted title of Certified Scrum Master to his already impressive cache of expert credentials, you’d definitely want him to be your Scrum Master.

But wait! Make sure you don’t ask Mr. Un what agile methods he uses to magically remove the obstacles and impediments to your success.

NFRs And QARs

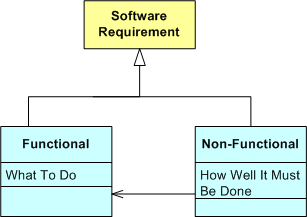

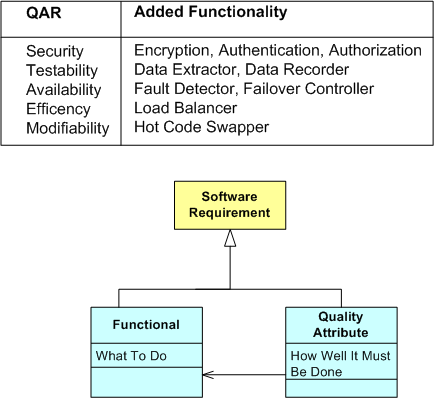

At the first level of decomposition, a software requirement can be classified as either “functional” or “non-functional“. A functional requirement (FR) specifies a value-added behavior/capability/property that the software system must exhibit during runtime in order for it to be deemed acceptable by its customers and users. A non-functional requirement (NFR) specifies how well one or more behaviors/capabilities/properties must perform.

Unlike FRs, which are nominally local, fine-grained, and verifiable early in the project, NFRs are typically global, coarse-grained, and unverifiable until a considerable portion of the system has been developed. Also, unlike FRs, NFRs often have cold, hard-to-meet, numbers associated with them:

- The system shall provide a response to any user request under a full peak load of 1000 requests per second within 100 milliseconds. (throughput, latency NFRs)

- The system shall be available for use 99.9999 percent of the time. (availability NFR)

- The system shall transition from the not-ready to ready within 5 seconds. (Domain-specific Performance NFR)

- The system shall be repairable by a trained technician within 10 minutes of the detection and localization of a critical fault. (Maintainability NFR)

- The system shall be capable of simultaneously tracking 1000 targets in a clutter-dominated environment. (Domain-specific Performance NFR)

- The system shall detect an air-breathing target with radar cross-section of 1 sq. meter at a range of 200 miles with a probability of 90 percent. (Domain-specific Performance NFR)

- The system shall produce range estimates within 5 meters of the true target position. (Domain-specific Performance NFR)

- The system shall provide TCP/IP, HTTP, CORBA, and DDS protocol support for interfacing with external systems. (Interoperability NFR)

During front-end system conception, NFRs are notoriously underspecified – if they’re formally specified at all. And yet, unlike many functional requirements, the failure to satisfy a single NFR can torpedo the whole effort and cause much downstream, career-ending, mischief after a considerable investment has been sunk into the development effort.

Since extra cross-cutting functionality (and extra hardware) must often be integrated into a system architecture (from the start) to satisfy one or more explicit/implicit NFRs, the term “non-functional requirement” is often a misnomer. Thus, as the SEI folks have stated, “Quality Attribute Requirement” (QAR) is a much more fitting term to specify the “how-well-a-system-must-perform” traits:

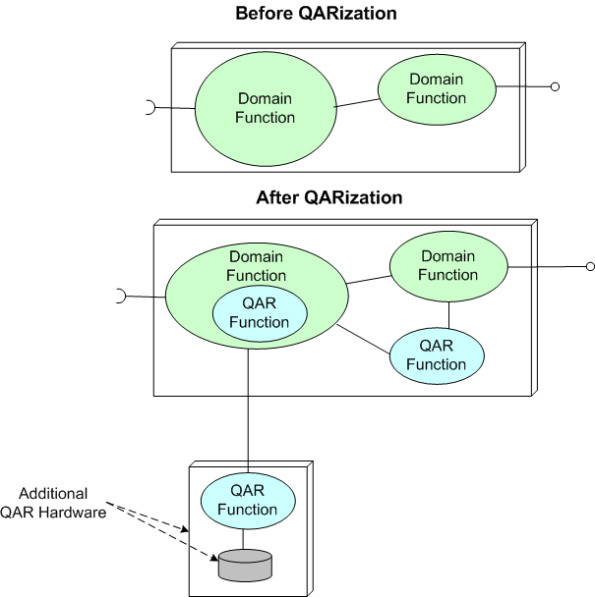

As the figure below illustrates, the “QARization” of a system can substantially increase its design and development costs. In addition, since the value added from weaving in any extra QAR software and hardware is mostly hidden under the covers to users and only becomes visible when the system gets stressed during operation, QARs are often (purposely?) neglected by financial sponsors, customers, users, AND developers. Stakeholders typically want the benefits without having to formally specify the details or having to pay the development and testing costs.

It’s sad, but like Rodney Dangerfield, QARs get no respect.