Archive

Metal, Not Paper

Ooh, ooh! BD00 just whispered an idea into my wax-filled ear. The nasty creature said: “Instead of a dull piece of paper, agile certification bodies should present their graduates with a shiny new medal. They can jack up the course fee to cover the price difference.”

Brilliant! Graduates would be able to strut around the open air office wearing their hard won bling on their chests. A gaggle of medals on the chest would nicely complement a $20K gold iWatch on the wrist and separate the winners from the losers.

But alas, never listen to what BD00, and I, as his sanctioned branding consultant, have to say. Never forget that….

Abstracting Away Some Details

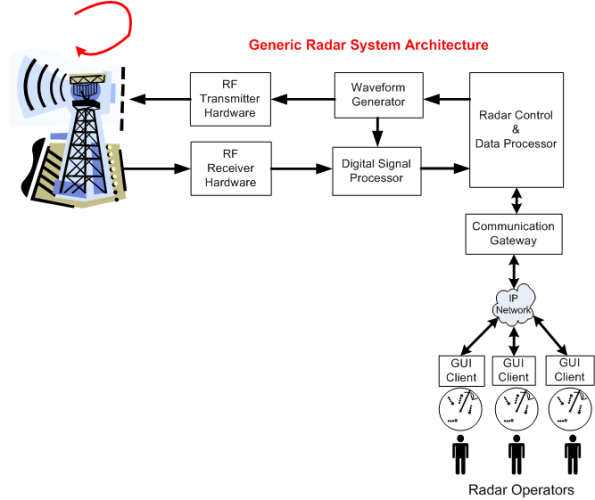

The following figure shows the general system architecture of a rotating, ground-based, radar whose mission is to detect and track “air breathing” targets. The chain of specially designed hardware and software subsystems provides radar operators with a 360 degree, real-time, surveillance picture of all the targets that fall within the physical range and elevation coverage capabilities of the Antenna and Transmit/Receive subsystems.

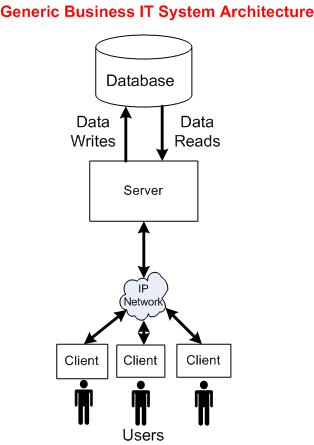

The following picture shows the general architecture of a business IT system. Unlike the specialized radar system architecture, this generic IT structure supports a wide range of application domains: insurance, banking, e-commerce, social media, etc.

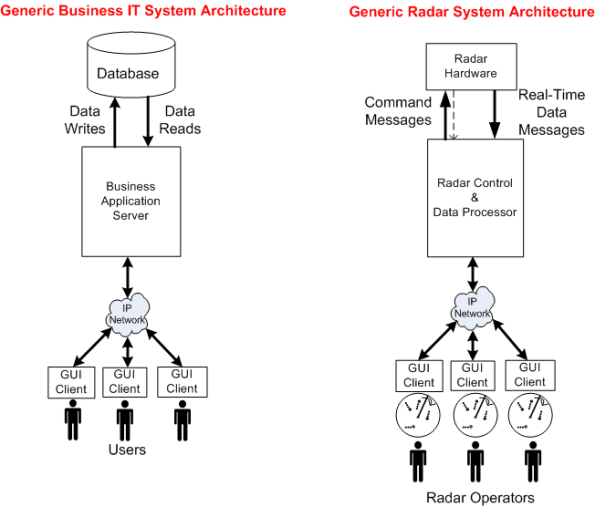

To explore the technical similarities/differences between the two platforms, let’s abstract away the details of everything to the left of the Radar Control & Data Processor and stuff them into a box called “Radar Hardware“. We’ll also tuck away the radar’s Communication Gateway functionality by placing it inside the Radar Control & Data Processor:

Now that we’ve used the power of abstraction to wrestle the original radar system architecture into a form similar to a business IT system, we can reason about some of the differences between the two structures.

Actually, I’m gonna stop here and leave the analysis of the technical similarities and differences as a thought experiment to you, dear reader. That’s because this is one of those posts that took me for freakin’ ever to write. I must have iterated over the draft at least 20 times during the past month. And of course, I had no master plan when I started writing it, so I hope you at least enjoy the pretty pictures.

Convergence To Zero

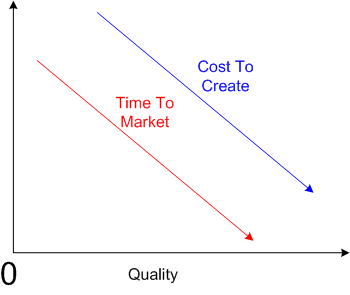

Maybe it’s just me, but I think that some people, especially managers and executives, auto-equate decreasing “cost to create” (CTC) and decreasing “time to market” (TTM) with increasing “quality“. Actually, since they’re always yapping about CTC and TTM, but rarely about about quality, perhaps they think there is no correlation between CTC/TTM and quality.

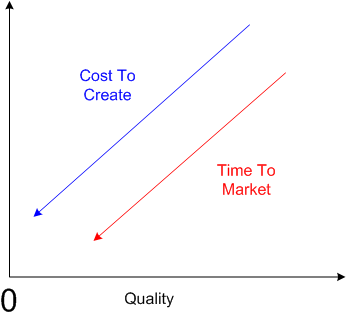

But consider the polar opposite, where decreasing the CTC and decreasing the TTM decreases quality.

I think both of the above cases are extreme generalities, but unless I’m missing something big, I do know one thing. In the limit, if you decrease the CTC and TTM to zero, you won’t produce anything; nada. Hence, quality converges to zero – even though the first graph in this post gives the illusion that it doesn’t.

Currently, in the real world, the iron triangle still rules:

Currently, in the real world, the iron triangle still rules:

Time, Cost, Quality: Pick any two at the expense of the third.

Note: If you’re a hip, new age person who likes to substitute the vague word “value” for the just-as-vague word “quality”, then by all means do so.

Convex, Not Linear

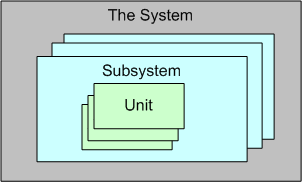

For a large, complex software system that can be represented via an instantiation of the above template, three levels of testing are required to be performed prior to fielding a system: unit, integration, and system. Unit testing shakes out some (hopefully most) of the defects in the local, concretely visible, micro-behavior, of each of possibly thousands of units. Integration testing unearths the emergent behaviors, both intended and unintended, of each individual subsystem assembly. System level, end-to-end, testing is designed to do the same for the intended/unintended behaviors of the whole shebang.

Now that the context has been set for this post, let’s put our myopic glasses on and zero in on the activity of unit testing. Unit testing is unarguably a “best practice“. However, just because it’s a best practice, does it mean we should, as one famous software character has hinted, strive to “turn the dials up to 10” on unit testing (or any other best practice?).

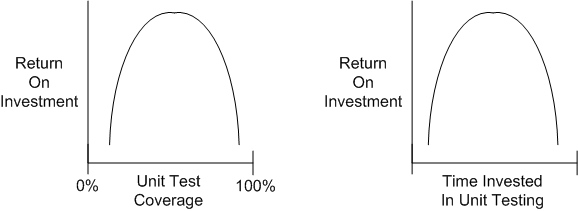

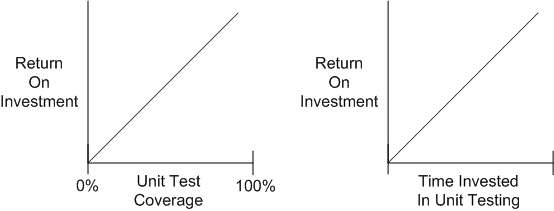

Check out these utterly subjective, unbacked-by-data, convex, ROI graphs:

If you believe these graphs hold true, then you would think that at some point during unit testing, you’d get more bang for the buck by investing your time in some other value-added task – such as writing another software unit or defining and running “higher level” integration and/or system tests on your existing bag of units.

Now, check out these utterly subjective, unbacked-by-data, linear, “turn the dials up to 10“, ROI graphs:

People who have drank the whole pitcher of unit-testing koolaid tend to believe that the linear model holds true. These miss-the-forest-for-the-trees people have no qualms about requiring their developers to achieve arbitrarily high unit test coverage percentages (80%, 85%, 90%, 100%) whilst simultaneously espousing the conflicting need to reduce cost and delivery time.

Given a fixed amount of time for unit + integration + system testing in a finite resource environment, how should that time be allocated amongst the three levels of testing? I don’t have any definitive answer, but when schedules get tight, as so often happens in the real world, something has gotta give. If you believe the convex unit testing model, then lowering unit test coverage mandates should be higher on your list of potential sacrificial lambs than cutting integration or system test time – where the emergent intended, and more importantly, unintended, behaviors are made visible.

Like Big Requirements Up Front (BRUF) and its dear sibling, Big Design Up Front (BDUF), perhaps we should add “Big Unit Testing Tragedy” (BUTT) to our bag of dysfunctional practices. But hell, it won’t be done. The linear thinkers seem to be in charge.

Note: Jim Coplien has been eloquently articulating the wastefulness of too much unit testing for years. This post is simply a similar take on his position:

Native, Managed, Interpreted

Someone asked on Twitter what a “native” app was. I answered with:

“There is no virtual machine or interpreter that a native app runs on. The code compiles directly into machine code.”

I subsequently drew up this little reference diagram that I’d like to share:

Given the source code for an application written in a native programming language, before you can run it, you must first compile the text into an executable image of raw machine instructions that your “native” device processor(s) know how to execute. After the compilation is complete, you command the operating system to load and run the application program image.

Given the source code for an application written in a “managed” programming language, you must also run the text through a compiler before launching it. However, instead of producing raw machine instructions, the compiler produces an intermediate image comprised of byte code instructions targeted for an abstract, hardware-independent, “virtual” machine. To launch the program, you must command the operating system to load/run the virtual machine image, and you must also command the virtual machine to load/run the byte code image that embodies the application functionality. During runtime, the virtual machine translates the byte code into instructions native to your particular device’s processor(s).

Given the source code for an application written in an “interpreted” programming language, you don’t need to pass it through a compiler before running it. Instead, you must command the operating system to load/run the interpreter, and you must also command the interpreter to load/run the text files that represent the application.

In general, moving from left to right in the above diagram, program execution speed decreases and program memory footprint increases for the different types of applications. A native program does not require a virtual machine or interpreter to be running and “managing” it while it is performing its duty. The tradeoff is that development convenience/productivity generally increases as you move from left to right. For interpreted programs, there is no need for any pre-execution compile step at all. For virtual machine based programs, even though a compile step is required prior to running the program, compilation times for large programs are usually much faster than for equivalent native programs.

Based on what I know, I think that pretty much sums up the differences between native, managed, and interpreted programs. Did I get it right?

Planet Agile

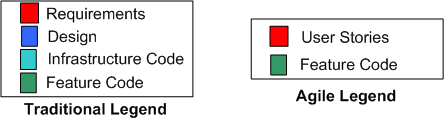

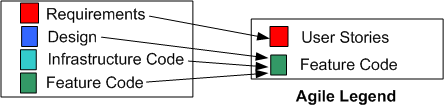

Because methodologists need an “enemy” to make their pet process look good, Agilistas use Traditional methods as their whipping boy. In this post, I’m gonna turn the tables by arguing as a Traditionalista (yet again) and using the exalted Agile methodology as my whipping boy. First, let’s start with two legends:

Requirements And User Stories

As you can see, the Agile legend is much simpler than the Traditional legend. On planet Agile, there aren’t any formal requirements artifacts that specify system capabilities, application functions, subsystems, inter-subsystem interfaces/interactions, components, or inter-component interfaces/interactions. There are only lightweight, independent, orthogonal, bite-sized “user stories“. Conformant Agile citizens either pooh-pooh away any inter-feature couplings or they simply ignore them, assuming they will resolve themselves during construction via the magical process of “emergence“.

Infrastructure Code And Feature Code

Unlike in the traditional world, in the Agile world there is no distinction between application-specific Infrastructure Code and Feature Code. Hell, it’s all feature code on planet Agile. Infrastructure Code is assumed as a given. However, since developers (and not external product users) write and use infrastructure code, utilizing “User Stories” to specify infrastructure code doesn’t cut it. Perhaps the Agilencia should rethink how they recommend capturing requirements and define two types of “stories“: “End User Stories” and “Infrastructure User Stories“.

Non-Existent Design

Regarding the process of “Design“, on planet Agile, thanks to TDD, the code is the design and the design is the code. There is no need to conceptually partition the code (which is THE one and only important artifact on planet Agile) beforehand into easily digestible, visually inspect-able, critique-able, levels of abstraction. To do so would be to steal precious coding time and introduce “waste” into the process. With the exception of the short, bookend events in a sprint (the planning & review/retrospective events), all non-coding activities are “valueless” in the mind of citizen Agile.

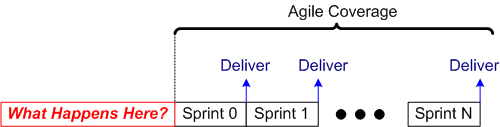

No Front End

When asked about “What happens before sprint 0?”, one agile expert told me on Twitter that “agile only covers software development activities“.

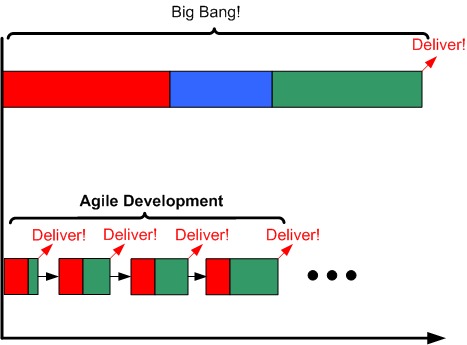

As the process timeline template below shows, there is no Sprint -1, otherwise known as “the Front End phase“, on planet Agile. Since the Agile leadership doesn’t recognize infrastructure code, or the separation of design from code, and no feature code is produced during its execution, there is no need for any investment in any Front End work. But hey, as you can plainly see, deliveries start popping out of an Agile process way before a Traditional process. In the specific example below, the nimble Agile team has popped out 4 deliveries of working software before the sluggish Traditional team has even hatched its first iteration. It’s just like planet Agile’s supreme leader asserts in his latest book – a 4X productivity improvement (twice the work in half the time).

Process Scalability

The flexible, dare I say “agile“, aspect of the Traditional development template is that it scales down. If the software system to be developed is small enough, or it’s an existing system that simply needs new features added to it, the “Front End” phase can indeed be entirely skipped. If so, then voila, the traditional development template reduces to a parallel series of incremental, evolutionary, sprints – just like the planet Agile template – except for the fact that infrastructure code development and integration testing are shown as first class citizens in the Traditional template.

On the other hand, the planet Agile template does not scale up. Since there is no such concept as a “Front End” phase on planet Agile, as a bona fide Agilista, you wouldn’t dare to plan and execute that phase even if you intuited that it would reduce long term development and maintenance costs for: you, your current and future fellow developers, and your company. To hell with the future. Damn it, your place on planet Agile is to get working software out the door as soon as possible. To do otherwise would be to put a target on your back and invite the wrath of the planet Agile politburo.

The Big Distortion

When comparing Agile with Traditional methods, the leadership on planet Agile always simplifies and distorts the Traditional development process. It is presented as a rigid, inflexible monster to be slain:

In the mind of citizen Agile, simply mentioning the word “Traditional” conjures up scary images of Niagara Falls, endless BRUF (Big Requirements Up Front), BDUF (Big Design Up Front), Big Bang Integration (BBI), and late, or non-existent, deliveries of working software. Of course, as the citizenry on planet Agile (and planet Traditional) knows, many Traditional endeavors have indeed resulted in failed outcomes. But for an Agile citizen to acknowledge Agile failures, let alone attribute some of those failures to the lack of performing any Front End due diligence, is to violate the Agile constitution and again place herself under the watchful eye of the Agile certification bureaucracy.

The Most Important Question

You may be wondering, since I’ve taken on the role of an unapologetic Traditionalista in this post, if I am an “Agile-hater” intent on eradicating planet Agile from the universe. No, I’m not. I try my best to not be an Absolutist about anything. Both planet Agile and planet Traditional deserve their places in the universe.

Perhaps the first, and most important, question to ask on each new software development endeavor is: “Do we need any Front End work, and if so, how much do we need?”

2000 Lines A Day

I was at a meeting once where a peer boasted: “It’s hard to schedule and convene code reviews when you’re writing 2000 lines of code a day“. Before I could open my big fat mouth, a fellow colleague beat me to the punch: “Maybe you shouldn’t be writing 2000 lines of code per day“.

Unless they run a pure software company (e.g. Google, Microsoft, Facebook), executive management is most likely a fan of cranking out more and more lines of code per day. Because of this, and the fact that cranking out more lines of code than the next guy gives them a warm and fuzzy feeling, I suspect that many developers have a similar mindset as my boastful peer.

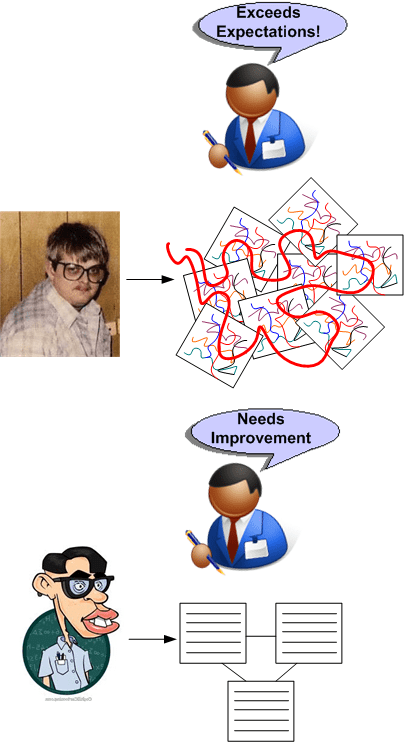

Unsurprisingly, the results of cranking out as much code per day as one can, can yield legacy code before it actually becomes legacy code:

- Huge classes and multi-page member functions with deeply nested “if” constructs inter-twined within multiple “for” loops.

- A seemingly random mix of public and private member objects.

- No comments.

- Inconsistent member and function naming.

- No unit tests.

- Loads of hard-coded magic numbers and strings.

- Tens of import statements.

Both I and you know this because because we’ve had to dive into freshly created cesspools with those “qualities” to add new functionality – even though “the code is only a tool” that isn’t a formal deliverable. In fact, we’ve most likely created some pre-legacy, legacy code cesspools ourselves.

The RGR Prayer

I recently watched an agile training video in which the sage on the stage made the audience repeat after him three times, the RGR prayer: “red, green, refactor“.

As I watched, I wondered how many of the repeaters were thinking “uh, this may be bullshit” while they uttered those three golden words from the sacred book of agile. It reminded me of those religious ceremonies my parents forced me to attend where the impeccably dressed, pew-dwelling flock, mindlessly stood up and parroted whatever the high priest dictated to them.

Let’s digress, but please bear with me for a moment and we’ll meet up with the RGR prayer again in short order.

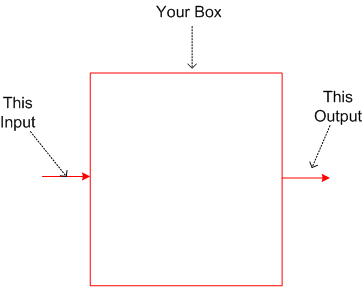

I know it’s not much to go by, but assume that you’re given the following task:

“Given this input, design and build a box that produces this output.”

Rising to the challenge, you concoct the following three design candidates upfront (OMG!) so you can trade them off against each other.

Which design candidate is “better“? The monolith (A), the multi-element network structure (B), or the two element pipeline (B)?

As always, it “depends“. If the functionality required to transform “this input” into “that output” is tiny (e.g. a trivial “Hello World” program) then the monolith is “best” in terms of understandability and latency (time delay from input to output). If the required functionality is large and non-linearly complex, then the multi-component network design is most likely the “best“. Somewhere in between lies the two element pipeline as the “best” design.

Hard core agilista consultants like our RGR priest and those dead set against the “smell” of any formal upfront requirements analysis or design activities would always argue: “all that time you spent upfront drawing pretty pictures and concocting design candidates was wasted labor. If you simply used that precious time to apply the RGR prayer through TDD (Test Driven Development), the best design, which you can’t ever know a-priori, would have emerged – IT ALWAYS DOES.”

See, I followed through on my commitment to weave our way back to the RGR prayer.

Where Specialists, Dependencies, And Handoffs Are Required

Take a minute to look around yourself and imagine how many interdependent chains of specialists and handoffs were required to produce the materials that make your life quite a bit more comfortable than our cave dwelling ancestors.

Total self sufficiency is a great concept, but if you had to do all the work to produce all of the things you take for granted, you wouldn’t be able to. You simply wouldn’t have enough time.

In software development, above a certain (unknown) level of complexity and size, specialists, dependencies, and handoffs are required to have any chance of getting the work done and the product integrated. Cross-functional teams, where every single person on the team knows how to design and code every functional area of a product, is an unrealistic pipe dream for anything but trivial products.

The Repo Of Shared Understanding

Documentation can be organized, structured, archived, searched. Verbal communications can’t.

Check out these two communication system configurations for developing software.

The system on the left, which depends (almost) solely on face-to-face collaboration, is the “agile” way. The system on the right, designed around a living, breathing, Repository Of Shared Understanding (ROSU) and supplemented by face-to-face conversation, is the “traditional” configuration.

As the previous paragraph implies, “agile” doesn’t recommend no documentation generation. It simply relegates the practice of document creation to the back of the bus. The idea, premised on the myth that documentation isn’t a required deliverable (in my industry it is) and the truth that programmers hate to write anything but code, is to supplement face-to-face communion with temporary, discardable, napkin scribblings and incomprehensible whiteboard snapshots.

Which system configuration do you think is more scalable? Which is more effective for long-lived, software-intensive products? Which do you think is better, more accommodating, for onboarding future team members? Which do you think is more effective for investigating/understanding/debugging system level failures (not unit level failures)?

Agilists will often bolster their “minimal documentation” approach with the assertion that requirements and design documents become obsolete as soon as the ink dries. Well yeah, if the team doesn’t continuously update its ROSU, then they’re right. But why is it such a big deal to keep the ROSU in synch with the code? The big deal is that it’s tough to sustain the discipline and resolve to so.