Archive

Not So Nice And Tidy

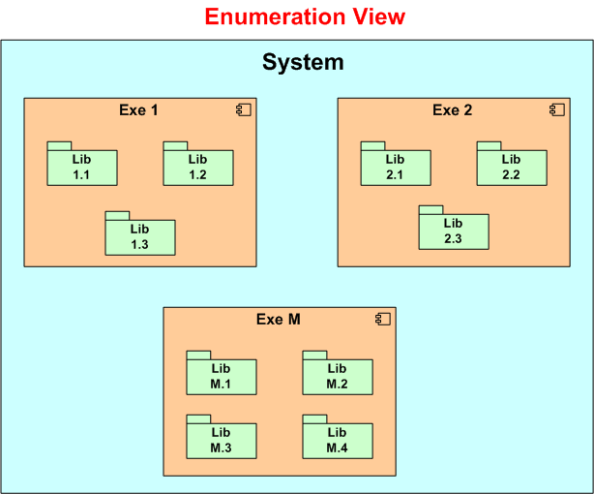

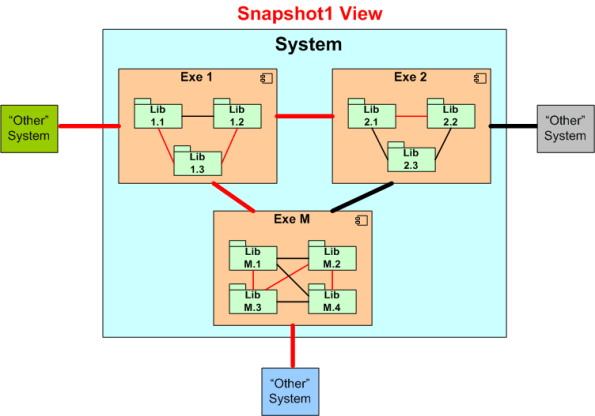

Assume we have a valuable, revenue-critical software system in operation. The figure below shows one nice and tidy, powerpoint-worthy way to model the system; as a static, enumerated set of executables and libraries.

Given the model above, we can express the size of the system as:

Now, say we run a tool on the code base and it spits out a system size of 200K “somethings” (lines of code, function points, loops, branches, etc).

What does this 200K number of “somethings” absolutely tell us about the non-functional qualities of the system? It tells us absolutely nothing. All we know at the moment is that the system is operating and supporting the critical, revenue generating processes of our borg. Even relatively speaking, when we compare our 200K “somethings” system against a 100K “somethings” system, it still doesn’t tell us squat about the qualities of our system.

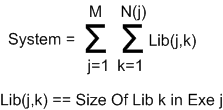

So, what’s missing here? One missing link is that our nice and tidy enumerations view and equation don’t tell us nuttin’ about what Russ Ackoff calls “the product of the interactions of the parts” (e.g Lib-to-Lib, Exe-Exe). To remedy the situation, let’s update our nice and tidy model with the part-to-part associations that enable our heap of individual parts to behave as a system:

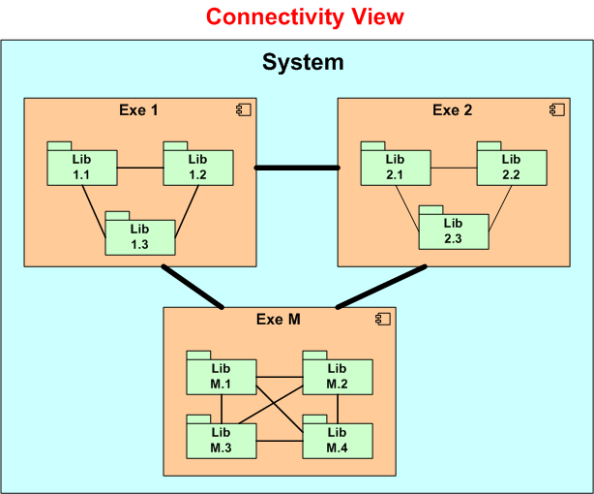

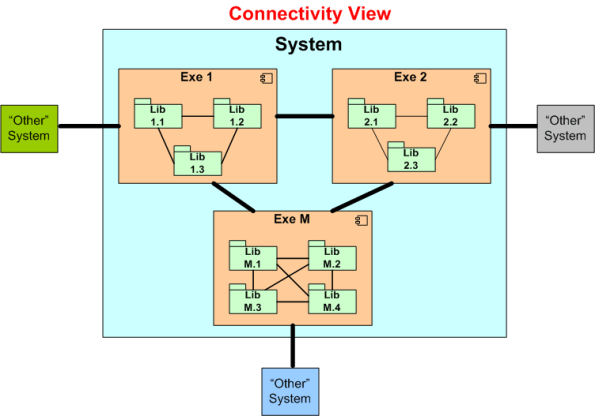

Our updated model is still nice and tidy, but just not as nice and tidy as before. But wait! We are still missing something important. We’re missing a visual cue of our system’s interactions with “other” systems external to us; you know, “them”. The “them” we blame when something goes wrong during operation with the supra-system containing us and them.

Our updated model is once again still nice and tidy, but just not as nice and tidy as before. Next, let’s take a single snapshot of the flow of (red) “blood” in our system at a given point of time:

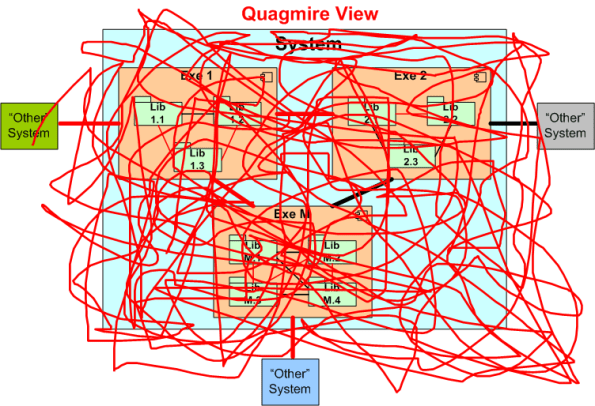

Finally, if we super-impose the astronomic number of all possible blood flow snapshots onto one diagram, we get:

D’oh! We’re not so nice and tidy anymore. Time for some heroic debugging on the bleeding mess. Is there a doctor in da house?

Hopping On The Anti-Fragile Bandwagon

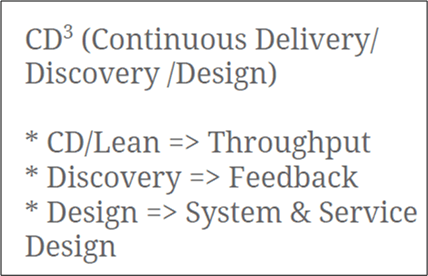

Since Martin Fowler works there, I thought ThoughtWorks Inc. must be great. However, after watching two of his fellow ThoughtWorkers give a talk titled “From Agility To Anti-Fragility“, I’m having second thoughts. The video was a relatively lame attempt to jam-fit Nassim Taleb’s authentic ideas on anti-fragility into the software development process. Expectedly, near the end of the talk the presenters introduced their “new” process for making your borg anti-fragile: “Continuous Delivery/Discovery/Design“. Lookie here, it even has a superscript in its title:

Having read Mr. Taleb’s four fascinating books, the one hour and twenty-six minute talk was essentially a synopsis of his latest book, “Anti-Fragile“. That was the good part. The ThoughtWorkers’ attempts to concoct techniques that supposedly add anti-fragility to the software development process introduced nothing new. They simply interlaced a few crummy slides with well-known agile practices (small teams, no specialists, short increments, co-located teams, etc) with the good slides explaining optionality, black/grey swans, convexity vs concavity, hormesis, and levels of randomness.

Understood, Manageable, And Known.

Our sophistication continuously puts us ahead of ourselves, creating things we are less and less capable of understanding – Nassim Taleb

It’s like clockwork. At some time downstream, just about every major weapons system development program runs into cost, schedule, and/or technical performance problems – often all three at once (D’oh!).

Despite what their champions espouse, agile and/or level 3+ CMMI-compliant processes are no match for these beasts. We simply don’t have the know how (yet?) to build them efficiently. The scope and complexity of these Leviathans overwhelms the puny methods used to build them. Pithy agile tenets like “no specialists“, “co-located team“, “no titles – we’re all developers” are simply non-applicable in huge, multi-org programs with hundreds of players.

Being a student of big, distributed system development, I try to learn as much about the subject as I can from books, articles, news reports, and personal experience. Thanks to Twitter mate @Riczwest, the most recent troubled weapons system program that Ive discovered is the F-35 stealth fighter jet. On one side, an independent, outside-of-the-system, evaluator concludes:

The latest report by the Pentagon’s chief weapons tester, Michael Gilmore, provides a detailed critique of the F-35’s technical challenges, and focuses heavily on what it calls the “unacceptable” performance of the plane’s software… the aircraft is proving less reliable and harder to maintain than expected, and remains vulnerable to propellant fires sparked by missile strikes.

On the other side of the fence, we have the $392 billion program’s funding steward (the Air Force) and contractor (Lockheed Martin) performing damage control via the classic “we’ve got it under control” spiel:

Of course, we recognize risks still exist in the program, but they are understood and manageable. – Air Force Lieutenant General Chris Bogdan, the Pentagon’s F-35 program chief

The challenges identified are known items and the normal discoveries found in a test program of this size and complexity. – Lockheed spokesman Michael Rein

All of the risks and challenges are understood, manageable, known? WTF! Well, at least Mr. Rein got the “normal” part right.

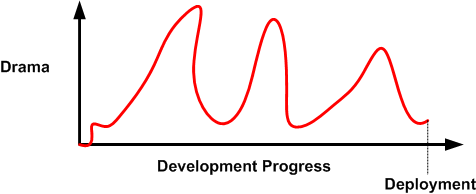

In spite of all the drama that takes place throughout a large system development program, many (most?) of these big ticket systems do eventually get deployed and they end up serving their users well. It simply takes way more sweat, time, and money than originally estimated to get it done.

Big Design, But Not All Upfront

When not ranting and raving on this blawg about “great injustices” (LOL) that I perceive are keeping the world from becoming a better place, I design, write, and test real-time radar system software for a living. I use the UML before, during, and after coding to capture, expose, and reason about my software designs. The UML artifacts I concoct serve as a high level coding road map for me; and a communication tool for subject matter experts (in my case, radar system engineers) who don’t know how to (or care to) read C++ code but are keenly interested in how I map their domain-specific requirements/designs into an implementable software design.

I’m not a UML language lawyer and I never intend to be one. Luckily, I’m not forced to use a formal UML-centric tool to generate/evolve my “bent” UML designs (see what I mean by “bent” UML here: Bend It Like Fowler). I simply use MSFT Visio to freely splat symbols and connections on an e-canvas in any way I see fit. Thus, I’m unencumbered by a nanny tool telling me I’m syntactically/semantically “wrong!” and rudely interrupting my thought flow every five minutes.

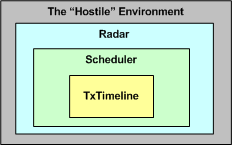

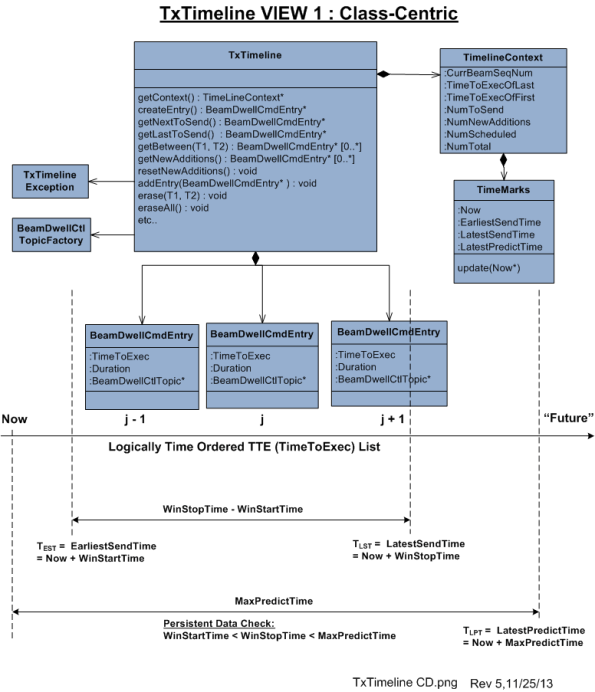

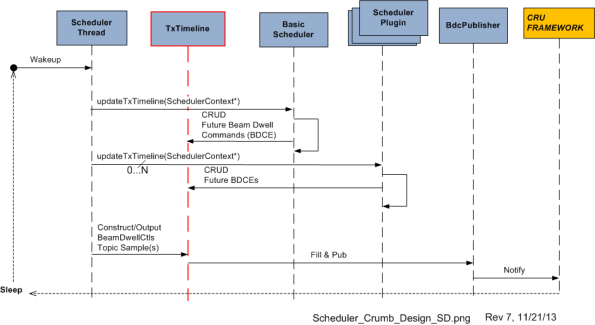

The 2nd graphic below illustrates an example of one of my typical class diagrams. It models a small, logically cohesive cluster of cooperating classes that represent the “transmit timeline” functionality embedded within a larger “scheduler” component. The scheduler component itself is embedded within yet another, larger scale component composed of a complex amalgam of cooperating hardware and software components; the radar itself.

When fully developed and tested, the radar will be fielded within a hostile environment where it will (hopefully) perform its noble mission of detecting and tracking aircraft in the midst of random noise, unwanted clutter reflections, cleverly uncooperative “enemy” pilots, and atmospheric attenuation/distortion. But I digress, so let me get back to the original intent of this post, which I think has something to do with how and why I use the UML.

The radar transmit timeline is where other necessarily closely coupled scheduler sub-components add/insert commands that tell the radar hardware what to do and when to do it; sometime in the future relative to “now“. As the radar rotates and fires its sophisticated, radio frequency pulse trains out into the ether looking for targets, the scheduler is always “thinking” a few steps ahead of where the antenna beam is currently pointing. The scheduler relentlessly fills the TxTimeline in real time with beam-specific commands. It issues those commands to the hardware early enough for the hardware to be able to queue, setup, and execute the minute transmit details when the antenna arrives at the desired command point. Geeze! I’m digressing yet again off the UML path, so lemme try once more to get back to what I originally wanted to ramble about.

Being an unapologetic UML bender, and not a fan of analysis-paralysis, I never attempt to meticulously show every class attribute, operation, or association on a design diagram. I weave in non-UML symbology as I see fit and I show only those elements I deem important for creating a shared understanding between myself and other interested parties. After all, some low level attributes/operations/classes/associations will “go away” as my learning unfolds and others will “emerge” during coding anyway, so why waste the time?

Notice the “revision number” in the lower right hand corner of the above class diagram. It hints that I continuously keep the diagram in sync with the code as I write it. In fact, I keep the applicable diagram(s) open right next to my code editor as I hack away. As a PAYGO practitioner, I bounce back and forth between code & UML artifacts whenever I want to.

The UML sequence diagram below depicts a visualization of the participatory role of the TxTimeline object in a larger system context comprised of other peer objects within the scheduler. For fear of unethically disclosing intellectual property, I’m not gonna walk through a textual explanation of the operational behavior of the scheduler component as “a whole“. The purpose of presenting the sequence diagram is simply to show you a real case example that “one diagram is not enough” for me to capture the design of any software component containing a substantial amount of “essential complexity“. As a matter of fact, at this current moment in time, I have generated a set of 7+ leveled and balanced class/sequence/activity diagrams to steer my coding effort. I always start coding/testing with class skeletons and I iteratively add muscles/tendons/ligaments/organs to the Frankensteinian beast over time.

In this post, I opened up my trench coat and showed you my… attempted to share with you an intimate glimpse into the way I personally design & develop software. In my process, the design is not done “all upfront“, but a purely subjective mix of mostly high and low level details is indeed created upfront. I think of it as “Big Design, But Not All Upfront“.

Despite what some code-centric, design-agnostic, software development processes advocate, in my mind, it’s not just about the code. The code is simply the lowest level, most concrete, model of the solution. The practices of design generation/capture and code slinging/testing in my world are intimately and inextricably coupled. I’m not smart enough to go directly to code from a user story, a one-liner work backlog entry, a whiteboard doodle, or a set of casual, undocumented, face-to-face conversations. In my domain, real-time surveillance radar systems, expressing and capturing a fair amount of formal detail is (rightly) required up front. So, screw you to any and all NoUML, no-documentation, jihadists who happen to stumble upon this post. 🙂

Pick Your Theory: X, Y, Or T

If you’re a student (or self-proclaimed/credentialed “expert“) of institutional behavior, there’s no doubt that you’ve heard of Doug MacGregor‘s famous Theory X and Theory Y worldviews regarding social attitudes within organizations. And, if you’re a manager who is not into political suicide, you at least publicly espouse allegiance to the more ethically pleasing Theory Y view.

Well, in “The Management Myth: Why the Experts Keep Getting it Wrong“, philosopher-turned-business-consultant-returned-philosopher Matt Stewart concocts an interesting, but perhaps more pragmatic, Theory T:

Theory T (for tragic): Some degree of conflict is inherent in all forms of social organization. Sometimes the self is at odds with the community, sometimes the community is at odds with itself, and sometimes, as Thomas Hobbes pointed out, it’s a war of all against all. – Matt Stewart

Perhaps shockingly, but not totally out of the realm of possibility, Matt concludes:

It (Theory Y) is an attempt to trick our ethical intuitions— that is, to make workers believe that they are being well treated when in fact they are being exploited.

In this unsettling but thought-tickling view, Mr. Stewart asserts that the aim of both the bad-X and good-Y theories is to ultimately exploit the workery, but only Theory X is transparently upfront about it.

Impedance Mismatch

The anecdotal evidence is overwhelming. Agile methods can work really well for many small teams and small projects. However, no matter what the expert, high-profile, “coaches” purport, the jury is still out regarding its scalability to large teams and large projects. In “How even agile development couldn’t keep this mega-project on track“, Nick Heath showcases the British disaster known as the £2.4bn “Universal Credit Programme“.

First, the sad fact:

…the UK government has had to write off at least £34m on the programme and delay the national launch for the project. The department in charge of the project, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), can’t guarantee the remainder of the £303m it has spent on the project so far will offer “good value” it said.

From the rest of Nick’s story, it becomes clear that agile methods weren’t really used to develop the software:

There was a two-year gap between the DWP starting the project design and build process, and the system going live in 2013.

The DWP experienced problems incorporating the agile approach into existing contracts, governance and assurance structures.

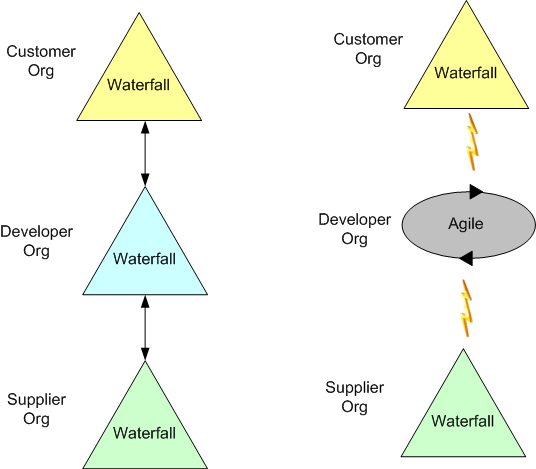

That second point is key. No matter how much a big org wants to be “agile“, it is heavily constrained by the hierarchical structures, stature-obsessed mindsets, byzantine processes, and form-filled procedures entrenched within not only itself, but also within its suppliers and customers. It’s a classic “system” problem where futzing around with one component may crash the whole system because of hardened interfaces and skin tight coupling.

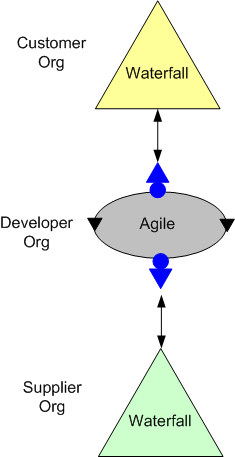

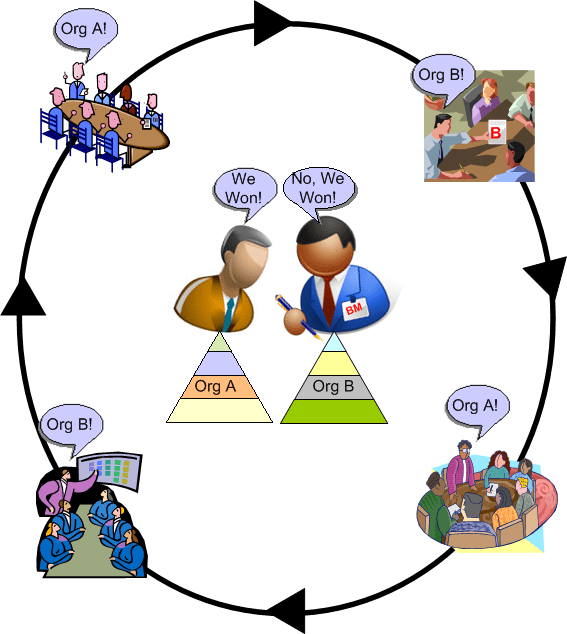

As the figure below shows, attempting to “agilize” a large component within an even larger, waterfall-centric, system creates impedance mismatches at every interface. The greater the mismatch, the less productive the system becomes. Information flow and understanding between components bog down while noise and distortion overwhelm the communication channels. In the worse case, the system stops producing value-added output and it would have been better to leave the old, inefficient, waterfall-centric system intact.

The only chance an agile-wanna-be component has at decoupling itself from the external waterfall insanity is to covertly setup a two-faced, agile<->waterfall protocol converter for each of its external interfaces. Good luck pullin’ that stunt off.

Same Old, Same Old

After stumbling across this announcement, “Navy orders Raytheon to stop work on next-gen radar“, I just had to laugh. It’s the same old, same old “iterative” process:

- The Department of Defense issues a request for proposals.

- The usual suspects (Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, Northrup Grumman, etc) submit bids.

- A winner is selected – Yay!

- The sore loser(s) protest the decision.

- By law, the decision must be revisited and re-evaluated.

- The decision is either upheld, or a new winner is selected.

- If a new winner is selected, the previous winner protests.

I’ve worked in the aerospace and defense industry for 30+ years and I’ve seen this dysfunctional, time and money wasting, game play over and over like clockwork. Tick tock, tick tock.

Sometimes the bid-win-protest cycle goes on for years and it takes longer for the hundreds of bureaucrats, lobbyists, committees, and politicians to resolve the dilemma than for the eventual winner to actually build the system. In addition, after all the political shenanigans have played out and the ultimate winner starts the ball rolling, the contract is sometimes cancelled in midstream after millions of dollars and engineering hours have been spent.

Despite repeated calls for procurement/acquisition process reform, the system is so big and there are so many intertwined players that any substantive change is virtually impossible. But hey, it’s taxpayer money. No problemo.

The System Always Fights Back – John Gall

Left And Right

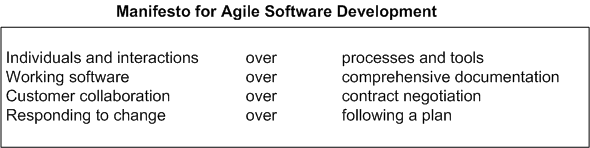

The Manifesto for Agile Software Development is rightly credited with launching the agile revolution and catalyzing the birth of methodologies like XP, DSDM, and Scrum. The following four major tenets supposedly underpin every single agile methodology.

In theory, not many people (with the exception of a pure bred bureaucrat) could argue effectively against preferring the soft left side over the hard right side of the table.

In practice, the situation is often much different than the theory. While espousing the need to operate in accordance with the left side, many so-called leaders stick to their 20th century guns behind the rhetoric. They demand process and tool compliance, dumpsters full of useless forms/documents/metrics, formal, penalty-laden contracts, and preposterously huge, upfront project plans.

BD00 posits that the reasons managers and executives demand conformance to the tenets on the right while espousing the ones on the left are one or more of the following:

- They don’t sincerely believe that the stuff on the left can possibly lead to higher quality products and faster delivery times than the stuff on the right.

- They can’t shed their personal fears of loss of control and loss in stature if they switch operating modes from the right to the left.

- They have no idea how to ignite the shift to the left (other than rhetoric).

- Their hands are tied because big customers (like the government and Fortune 500 companies) demand all the hulking, time-consuming, and expensive stuff on the right.

- They’ve made tons of money operating in accordance with the principles on the right both before and (many years) after the introduction of the agile manifesto.

Maybe that’s why I chuckle every time this quote comes to mind:

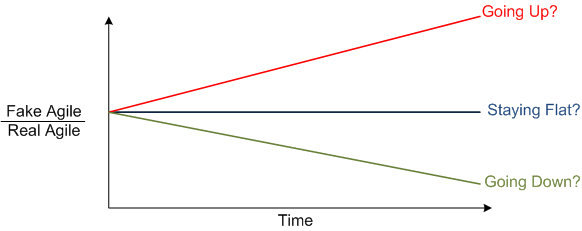

Everybody’s doing agile these days, even those who aren’t. – Scott Ambler

What do you think, dear reader? Are there any other reasons that should be added to the list? Do you think that the ratio of fake-to-real agile orgs is high or low? Is it increasing or decreasing with time?

All Forked Up

I dunno who said it, but paraphrasing whoever did:

Science progresses as a succession of funerals.

Even though more accurate and realistic models that characterize the behavior of mass and energy are continuously being discovered, the only way the older physics models die out is when their adherents kick the bucket.

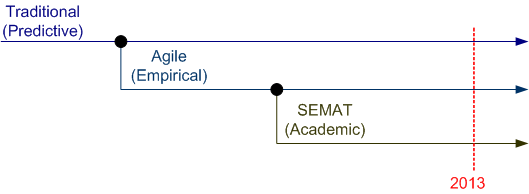

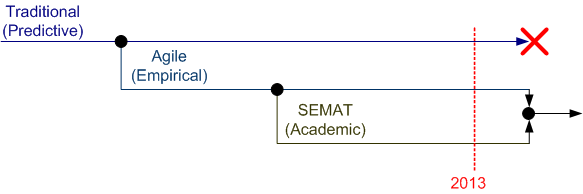

The same dictum holds true for software development methodologies. In the beginning, there was the Traditional (a.k.a waterfall) methodology and its formally codified variations (RUP, MIL-STD-498, CMMI-DEV, your org’s process, etc). Next, came the Agile fork as a revolutionary backlash against the inhumanity inherent to the traditional way of doing things.

The most recent fork in the methodology march is the cerebral SEMAT (Software Engineering Method And Theory) movement. SEMAT can be interpreted (perhaps wrongly) as a counter-revolution against the success of Agile by scorned, closet traditionalists looking to regain power from the agilistas.

On the other hand, perhaps the Agile and SEMAT camps will form an alliance and put the final nail in the coffin of the old traditional way of doing things before its adherents kick the bucket.

SEMAT co-creator Ivar Jacobson seems to think that hitching SEMAT to the Agile gravy train holds promise for better and faster software development techniques.

SEMAT co-creator Ivar Jacobson seems to think that hitching SEMAT to the Agile gravy train holds promise for better and faster software development techniques.

Who knows what the future holds? Is another, or should I say, “the next“, fork in the offing?