Archive

My “Status” As Of 09-27-09

I recently finished a 2 month effort discovering, developing, and recording a state machine algorithm that produces a stream of integrated output “target” reports from a continuous stream of discrete, raw input message fragments. It’s not rocket science, but because of the complexity of the algorithm (the devil’s always in the details), a decision was made to emulate this proprietary algorithm in multiple, simulated external environmental scenarios. The purpose of the emulation-plus-simulation project is to work out the (inevitable) kinks in the algorithm design prior to integrating the logic into an existing product and foisting it on unsuspecting customers :^) .

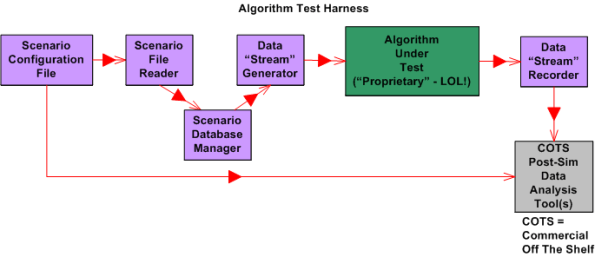

The “bent” SysML diagram below shows the major “blocks” in the simulator design. Since there are no custom hardware components in the system, except for the scenario configuration file, every SysML block represents a software “class”.

Upon launch, the simulator:

- Reads in a simple, flat, ASCII scenario configuration file that specifies the attributes of targets operating in the simulated external environment. Each attribute is defined in terms of a <name=value> token pair.

- Generates a simulated stream of multiplexed input messages emitted by the target constellation.

- Demultiplexes and processes the input stream in accordance with the state machine algorithm specification to formulate output target reports.

- Records the algorithm output target report stream for post-simulation analysis via Commercial Off The Shelf (COTS) tools like Excel and MATLAB.

I’m currently in the process of writing the C++ code for all of the components except the COTS tools, of course. On Friday, I finished writing, unit testing, and integration testing the “Simulation Initialization” functionality (use case?) of the simulator.Yahoo!

The diagram below zooms in on the front end of the simulator that I’ve finished (100% of course) developing; the “Scenario File Reader” class, and the portion of the in-memory “Scenario Database Manager” class that stores the scenario configuration data in the two sub-databases.

The next step in my evil plan (moo ha ha!) is to code up, test, and integrate the much-more-interesting “Data Stream Generator” class into the simulator without breaking any of the crappy code that has already been written. 🙂

If someone (anyone?) actually reads this boring blog and is interested in following my progress until the project gets finished or canceled, then give me a shoutout. I might post another status update when I get the “Data Stream Generator” class coded, tested, and integrated.

What’s your current status?

Architectural, Mechanistic, And Detailed

Bruce Powel Douglass is one of my favorite embedded systems development mentors. One of his ideas is to categorize the activity of design into three levels of increasingly detailed abstraction:

- Architectural (5 views)

- Mechanistic

- Detailed

The SysML figure below tries to depict the conceptual differences between these levels. (Even if you don’t know the SysML, can you at least viscerally understand the essence of what the drawings are attempting to communicate?)

Since the size, algorithmic density, and safety critical nature of the software intensive systems that I’ve helped to develop require what the agile community mocks as BDUF (Big Design Up Front), I’ve always communicated my “BDUF” designs in terms of the first and third abstractions. Thus, the mechanistic design category is sort of new to me. I like this category because it shortens the gulf of understanding between the architectural and the detailed design levels of abstraction. According to Mr. Douglass, “mechanistic design” is the act of optimizing a system at the level of an individual collaboration ( a set of UML classes or SysML blocks working closely together to realize a single use case). From now on, I’m gonna follow his three tier taxonomy in communicating future designs, but only when it’s warranted, of course (I’m not a religious zealot for or against any method), .

BTW, if you don’t do BDUF, you might get CUDO (Crappy and Unmaintanable Design Out back). Notice that I said “might” and not “will”.

SysML Diagram Headers

The Systems Modeling Language, SysML, is both an extension and a subset of the UML. SysML defines a “frame” that serves as the context for a given diagram’s content. As the diagram below shows, each frame contains a header compartment that houses 4 text elements which characterize the diagram. The two items in brackets are optional.

While learning the SysML, I was often confused as to the order of the header items and their meanings. My first thought when I saw the frame header was; “why are there so many freakin’ header entries; why not just one or two?”. I still get confused, but after studying a bunch of sample diagrams from System Engineering With SysML/UML: Modeling, Analysis, Design and A Practical Guide to SysMLThe Systems Modeling Language, I think that I have almost figured it out.

With the aid of the two previously mentioned references, I constructed the table below. There are 9 enumerated SysML diagrams, so understanding what the “diagram kind” header field means is trivial. It’s the optional “model element” header item that continues to confuse me. As you can see from the table, the types of “model element(s)” that can appear within the first 6 diagrams are fixed and finite. However, the last three are open ended.

The problem for me is determining what the set of all “model element types” is. Is it a finite set of enumerations like the “diagram kind” header entry, or is it free form and ad-hoc? Does anyone know what the answer is?

Distributed Vs. Centralized Control

The figure below models two different configurations of a globally controlled, purposeful system of components. In the top half of the figure, the system controller keeps the producers aligned with the goal of producing high quality value stream outputs by periodically sampling status and issuing individualized, producer-specific, commands. This type of system configuration may work fine as long as:

- the producer status reports are truthful

- the controller understands what the status reports mean so that effective command guidance can be issued when problems manifest.

If the producer status reports aren’t truthful (politics, culture of fear, etc.), then the command guidance issued by the controller will not be effective. If the controller is clueless, then it doesn’t matter if the status reports are truthful. The system will become “hosed”, because the inevitable production problems that arise over time won’t get solved. As you might guess, when the status reports aren’t truthful and the controller is clueless, all is lost. Bummer.

The system configuration in the bottom half of the figure is designed to implement the “trust but verify” policy. In this design, the global controller directly receives samples of the value streams in addition to the producer status reports. The integration of value stream samples to the information cache available to the controller takes care of the “untruthful status report” risk. Again, if the controller is clueless, the system will get hosed. In fact, there is no system configuration that will work when the controller is incompetent.

How many system controllers do you know that actually sample and evaluate value stream outputs? For those that don’t, why do you think they don’t?

The system design below says “syonara dude” to the global omnipotent and omniscient controller. Each producer cell has its own local, closely coupled, and knowledgeable controller. Each local controller has a much smaller scope and workload than the previous two monolithic global controller designs. In addition, a single clueless local controller may be compensated for if the collective controller group has put into place a well defined, fair, and transparent set of criteria for replacement.

What types of systems does your organization have in place? Centrally controlled types, distributed control types, a mixture of both, hybrids? Which ones work well? How do you see yourself in your org? Are you a producer, a local controller, both a local controller and a producer, an overconfident global controller, a narcissistic controller of global controllers, a supreme controller of controllers who control other controllers who control yet other controllers? Do you sample and evaluate the value stream?

UML and SysML Behavior Modeling

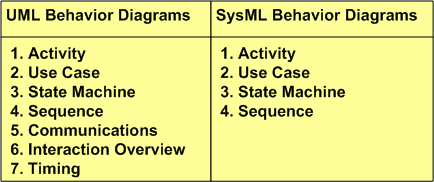

Most interesting systems exhibit intentionally (and sometimes unintentionally) rich behavior. In order to capture complex behavior, both the UML and its SysML derivative provide a variety of diagrams to choose from. As the table below shows, the UML defines 7 behavior diagram types and the SysML provides a subset of 4 of those 7.

Activity diagrams are a richer, more expressive enhancement to the classic, stateless, flowchart. Use case diagrams capture a graphical view of high level, text-based functional requirements. State machine diagrams are used to model behaviors that are a function of current inputs and past history. Sequence diagrams highlight the role of “time” in the protocol interactions between SysML blocks or UML objects.

What’s intriguing to me is why the SysML didn’t include the Timing diagram in its behavioral set of diagrams. The timing diagram emphasizes the role of time in a different and more precise way than the sequence diagram. Although one can express precise, quantitative timing constraints on a sequence diagram, mixing timing precision with protocol rules can make the diagram much more complicated to readers than dividing the concerns between a sequence diagram and timing diagram pair. Exclusion of the timing diagram is even more mysterious to me because timing constraints are very important in the design of hard/soft real-time systems. Incorrect timing behavior in a system can cause at least as much financial or safety loss as the production of incorrect logical outputs. Maybe the OMG and INCOSE will reconsider their decision to exclude the timing diagramin their next SysML revision?

SYSMOD Process Overview

Besides the systemic underestimation of cost and schedule, I believe that most project overruns are caused by shoddy front end system engineering (but that doesn’t happen in your org, right?). Thus, I’ve always been interested and curious about various system engineering processes and methods (I’ve even developed one myself – which was ignored of course 🙂 ). Tim Weilkiens, author of System Engineering with SysML/UML, has developed a very pragmatic and relatively lightweight system engineering process called SYSMOD. He uses SYSMOD as a framework to teach SysML in his book.

The figure below shows a summary of Mr. Weilkiens’s SYSMOD process in a 2 level table of activities. All of SYSMOD’s output artifacts are captured and recorded in a set of SysML diagrams, of course. Understandably, the SYSMOD process terminates at the end of the system design phase, after which the software and hardware design phases start. Like any good process, SYSMOD promotes an iterative development philosophy where the work at any downstream point in the process can trigger a revisit to previous activities in order to fix mistakes and errors made because of learning and new knowledge discovery.

The attributes that I like most about SYSMOD are that it:

- Seamlessly blends the best features of both object-oriented and structured analysis/design techniques together.

- Highlights data/object/item “flows” – which are usually relegated to the background as second class citizens in pure object-oriented methods.

- Starts with an outside-in approach based on the development of a comprehensive system context diagram – as opposed to just diving right into the creation of use cases.

- Develops a system glossary to serve as a common language and “root” of shared understanding.

How does the SYSMOD process compare to the ambiguous, inconsistent, bloated, one-way (no iterative loopbacks allowed), and high latency system engineering process that you use in your organization 🙂 ?

SysML Resources

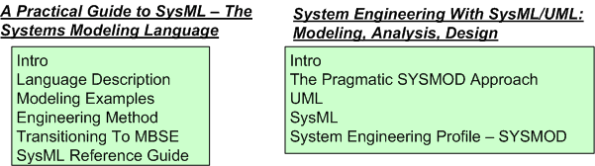

Unlike the UML, the SysML has relatively few books and articles from which to learn the language in depth. The two (and maybe only?) SysML books that I’ve read are:

System Engineering With SysML/UML: Modeling, Analysis, Design – Tim Weilkiens

A Practical Guide to SysMLThe Systems Modeling Language – Sanford Friedenthal; Alan Moore; Rick Steiner

IMHO, they are both terrific tools for learning the SysML and they’re both well worth the investment. Thus, I heartily recommend them both for anyone who’s interested in the language.

The books’ authors take different approaches to teaching the SysML. Even though the word “practical” is embedded in Friedenthal’s title, I think that Weilkiens book is less academic and more down to earth. Friendenthal takes a method-independent path toward communicating the SysML’s notation, syntax and semantics, while Weilkiens introduces his own pragmatic SYSMOD methodology as the primary teaching vehicle. Weilkiens examples seem less “dense” and more imbibable (higher drinkability :-)) than Friedenthal’s, but Friedenthal has examples from more electro-mechanical system “types”.

What I liked best about Weilkiens’s book is that in addition to the “what”, he does a splendid job explaining the “why” behind a lot of the SysML notation and symbology. You will easily conclude that he’s passionate about the subject and that he’s eager to teach you how to understand and use the SysML. Friedenthal’s book has an excellent and thorough SysML reference in an appendix. It’s great for looking up something you need to use but you forgot the details.

The Venerable Context Diagram

Since the method was developed before object-oriented analysis, I was weaned on structured analysis for system development. One of the structured analysis tools that I found most useful was (and still is) the context diagram. Developing a context diagram is the first step at bounding a problem and clearly delineating what is my responsibility and what isn’t. A context diagram publicly and visibly communicates what needs to be developed and what merely needs to be “connected to” – what’s external and what’s internal.

After learning how to apply object-oriented analysis, I was surprised and dismayed to discover that the context diagram was not included in the UML (or even more surprisingly, the SysML) as one of its explicitly defined diagrams. It’s been replaced by the Use Case Diagram. However, after reading Tim Weilkiens’s Systems Engineering With SysML/UML: Modeling, Analysis, Design, I think that he solved the exclusion mystery.

….it wasn’t really fitting for a purely object-oriented notation like UML to support techniques from the procedural world. Fortunately the times when the procedural world and the object-oriented world were enemies and excluded each other are mostly overcome. Today, proven techniques from the procedural world are not rejected in object orientation, but further developed and integrated in the paradigm.

Isn’t it funny how the exclusive “either or” mindset dominates the inclusive “both and” mindset in the engineering world? When a new method or tool or language comes along, the older method gets totally rejected. The baby gets thrown out with the bathwater as a result of ego and dualistic “good-bad” thinking.

“Nothing is good or bad, thinking makes it so.” – William Shakespeare

Mista Level

“Design is an intimate act of communication between the designer and the designed” – W. L. Livingston

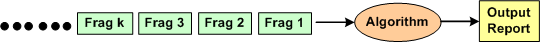

I’m currently in the process of developing an algorithm that is required to accumulate and correlate a set of incoming, fragmented messages in real-time for the purpose of producing an integrated and unified output message for downstream users.

The figure below shows a context diagram centered around the algorithm under development. The input is an unending, 24×7, high speed, fragmented stream of messages that can exhibit a fair amount of variety in behavior, including lost and/or corrupted and/or misordered fragments. In addition, fragmented message streams from multiple “sources” can be interlaced with each other in a non-deterministic manner. The algorithm needs to: separate the input streams by source, maintain/update an internal real-time database that tracks all sources, and periodically transmit source-specific output reports when certain validation conditions are satisfied.

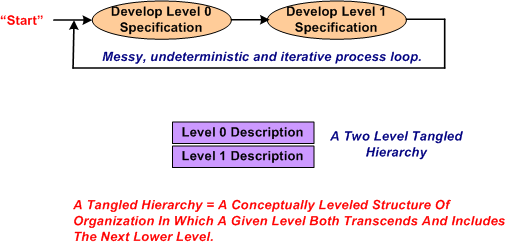

After studying literally 1000s of pages of technical information that describe the problem context that constrains the algorithm, I started sketching out and “playing” with candidate algorithm solutions at an arbitrary and subjective level of abstraction. Call this level of abstraction level 0. After looping around and around in the L0 thought space, I “subjectively decided” that I needed a second, more detailed but less abstract, level of definition, L1.

After maniacally spinning around within and between the two necessarily entangled hierarchical levels of definition, I arrived at a point of subjectively perceived stability in the design.

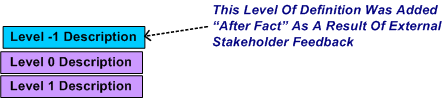

After receiving feedback from a fellow project stakeholder who needed an even more abstract level of description to communicate with other, non-development stakeholders, I decided that I mista level. However, I was able to quickly conjure up an L-1 description from the pre-existing lower level L0 and L1 descriptions.

Could I have started the algorithm development at L-1 and iteratively drilled downward? Could I have started at L1 and iteratively “syntegrated” upward? Would a one level-only (L-1, L0, or L1) specification be sufficient for all downstream stakeholders to use? The answers to all these questions, and others like them are highly subjective. I chose the jagged and discontinuous path that I traversed based on real-time situational assessment in the now, not based on some one-size-fits-all, step-by-step corpo approved procedure.

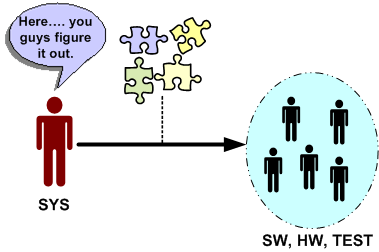

No Good Deed

Let’s say that the system engineering culture at your hierarchically structured corpo org is such that virtually all work products handed off (down?) to hardware, software and test engineers are incomplete, inconsistent, fragmented, and filled with incomprehensible ambiguity. Another word that describes this type of low quality work is “camouflage”. Since it is baked into the “culture”, camouflage is expected, it’s taken for granted, and it’s burned into everyone’s mind that “that’s the way it is and that’s the way it always will be”.

Now, assume that someone comes along and breaks from the herd. He/she produces coherent, understandable, and directly usable outputs for the SW and HW and TEST engineers to make rapid downstream progress. How do you think the maverick system engineer would be treated by his/her peers? If you guessed: “with open arms”, then you are wrong. Statements like “that’s too much detail”, “it took too much time”, “you’re not supposed to do that”, “that’s not what our process says we should do”, etc, will reign down on the maverick. No good deed goes unpunished. Sic.

Why would this seemingly irrational and dysfunctional behavior occur? Because hirearchical corpo cultures don’t accept “change” without a fight, regardless of whether the change is good or bad. By embracing change, the changees have to first acknowledge the fact that what they were doing before the change wasn’t working. For engineers, or non-engineers with an engineering mindset of infallibility, this level of self-awareness doesn’t exist. If a maverick can’t handle the psychological peer pressure to return to the norm and produce shoddy work products, then the status quo will remain entrenched. Sadly but surely, this is what everyone wants, including management, and even more outrageously, the HW, SW, and TEST engineers. Bummer.