Archive

Scrummin’ For The Ilities

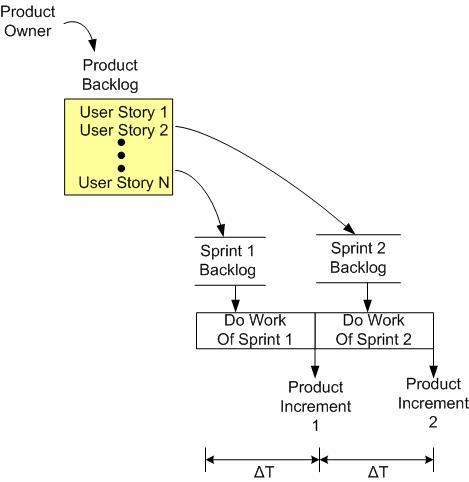

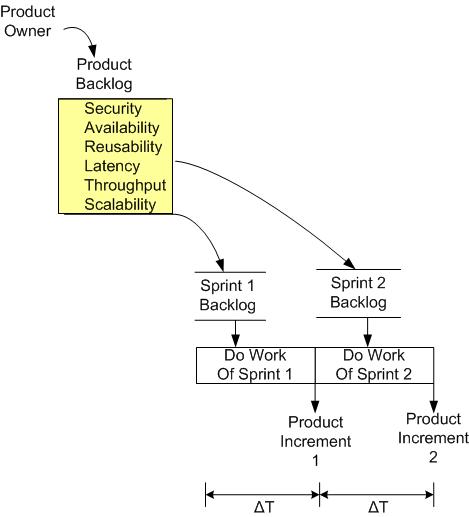

Whoo hoo! The product owner has funded our project and we’ve spring-loaded our backlog with user stories. We’re off struttin’ and scrummin’ our way to success:

But wait! Where are the “ilities” and the other non-functional product requirements? They’re not in your backlog?

Uh, we don’t do “ilities“. It’s not agile, it’s BDUF (Big Design Up Front). We no need no stinkin’ arkitects cuz we’re all arkitects. Don’t worry. These “ilities” thingies will gloriously emerge from the future as we implement our user stories and deliver working increments every two weeks – until they stop working.

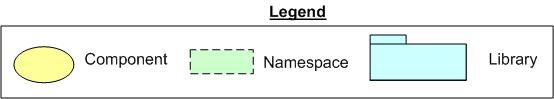

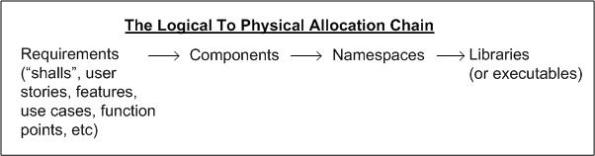

Components, Namespaces, Libraries

Regardless of which methodology you use to develop software, the following technical allocation chain must occur to arrive at working source code from some form of requirements:

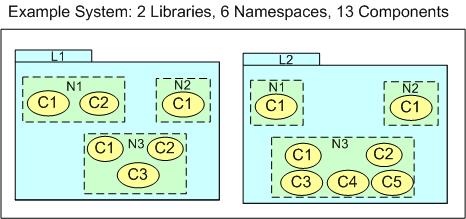

The figure below shows a 2/6/13 end result of the allocation chain for a hypothetical example project. How the 2/6/13 combo was arrived at is person and domain-specific. Given the same set of requirements to N different, domain-knowledgeable people, N different designs will no doubt be generated. Person A may create a 3/6/9 design and person B may conjure up 4/8/16 design.

Given a set of static or evolving requirements, how should one allocate components to namespaces and libraries? The figure below shows extreme 1/1/13 and 13/13/13 cases for our hypothetical 13 component example.

As the number of components, N, in the system design gets larger, the mindless N/N/N strategy becomes unscalable because of an increasing dependency management nightmare. In addition to deciding which K logical components to use in their application, library users must link all K physical libraries with their application code. In the mindless 1/1/N strategy, only one library must be linked with the application code, but because of the single namespace, the design may be harder to logically comprehend.

Expectedly, the solution to the allocation problem lies somewhere in between the two extremes. Arriving at an elegant architecture/design requires a proactive effort with some upfront design thinking. Domain knowledge and skillful application of the coupling-cohesion heuristic can do the trick. For large scale systems, letting a design emerge won’t.

Emergent design works in nature because evolution has had the luxury of millions of years to get it “right“. Even so, according to angry atheist Richard Dawkins, approximately 99% of all “deployed” species have gone extinct – that’s a lot of failed projects. In software development efforts, we don’t have the luxury of million year schedules or the patience for endless, random tinkering.

Burn Baby Burn

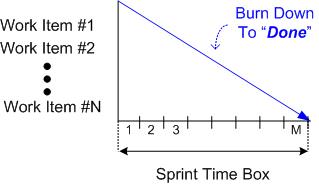

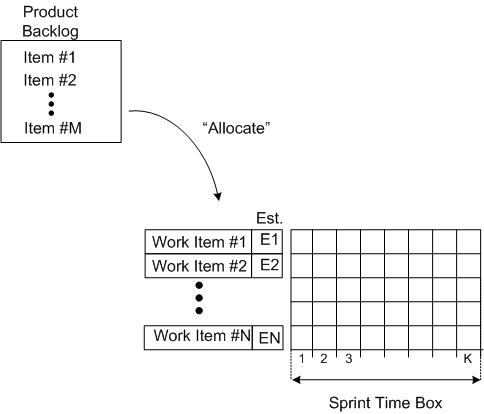

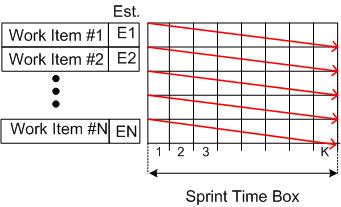

The “time-boxed sprint” is one of the star features of the Scrum product development process framework. During each sprint planning meeting, the team estimates how much work from the product backlog can be accomplished within a fixed amount of time, say, 2 or 4 weeks. The team then proceeds to do the work and subsequently demonstrate the results it has achieved at the end of the sprint.

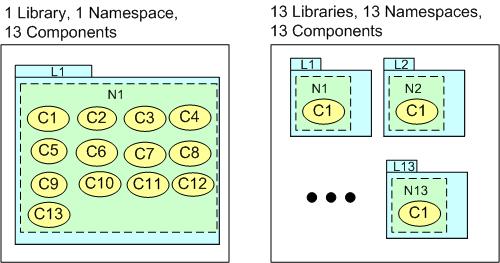

As a fine means of monitoring/controlling the work done while a sprint is in progress, some teams use an incarnation of a Burn Down Chart (BDC). The BDC records the backlog items on the ordinate axis, time on the abscissa axis, and progress within the chart area.

The figure below shows the state of a BDC just prior to commencing a sprint. A set of product backlog items have been somehow allocated to the sprint and the “time to complete” each work item has been estimated (Est. E1, E2….).

At the end of the sprint, all of the tasks should have magically burned down to zero and the BDC should look like this:

So, other than the shortened time frame, what’s the difference between an “agile” BDC and the hated, waterfall-esque, Gannt chart? Also, how is managing by burn down progress any different than the hated, traditional, Earned Value Management (EVM) system?

So, other than the shortened time frame, what’s the difference between an “agile” BDC and the hated, waterfall-esque, Gannt chart? Also, how is managing by burn down progress any different than the hated, traditional, Earned Value Management (EVM) system?

I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by – Douglas Adams

In practice, which of the outcomes below would you expect to see most, if not all, of the time? Why?

We need to estimate how many people we need, how much time, and how much money. Then we’ll know when we’re running late and we can, um, do something.

Fluency And Maturity

After reading about Martin Fowler‘s “levels of agile fluency”, I decided to do a side-by-side exploration of his four levels of fluency with the famous (infamous?) five “levels of CMMI maturity“:

As you can easily deduce, the first difference that I noticed was that

The SEI focuses on the process. Fowler focuses on the team of people.

Next, I noticed:

To the SEI, “proactive” is good and “reactive” is bad. Proactive vs. reactive seems to be a “don’t care” to Fowler.

The SEI emphasizes the attainment of “control“. Fowler emphasizes the attainment of “business value“.

While writing this post, I really wanted to veer off into a rant demonizing the SEI list for being so mechanistically Newtonian. However, I stepped back, decided to take the high road, and formed the following meta-conclusion:

The SEI & Fowler lists aren’t necessarily diametrically opposed.

Perhaps the nine levels can be intelligently merged into a brilliant hybrid that balances both people and process (like the Boehm/Turner attempt).

What do you think? Is the side-by-side comparison fair, or is it an apple & oranges monstrosity?

Shortcutting The Shortcut

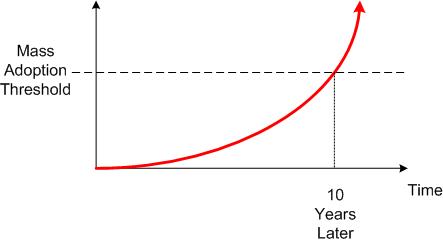

BD00 has heard from several sources that it takes about 10 years for a winning technology to make it into the mainstream. After starting off with a slow uptake due to fear and uncertainty, the floodgates open up and everybody starts leveraging the technology to make more money and greater products.

This 10 year rule of thumb surely applies to the “agile” movement, which recently celebrated its 10th anniversary. But as the new book below shows, the frenzy can get laughably outta control.

Not to rag too much on Mr. Goldstein, but sheesh. As if Scrum is not “fast” enough already? Now we’re patronizingly told that we need “intelligent” shortcuts to make it even faster. Plus, we idiots need to learn what these shortcuts are and how to apply them in a “step-by-step” fashion from a credentialed sage-on-a-stage. Hey, we must be idjets cuz, despite the beautiful simplicity of Scrum, Mr. Goldstein implies that we keep screwing up its execution.

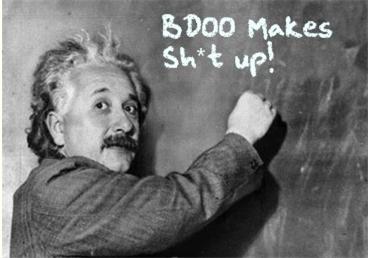

As usual, BD00 hasn’t read the ground breaking new book. And he has no plan to read it. And he has no plan to stop writing about topics he hasn’t researched “deeply“. Thus, keep reminding yourself that:

Possibly The Worst Ever

“It is wrong to suppose that if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it – a costly myth” – W. E. Deming

“You can only measure 3% of what matters.” – W. E. Deming

Even though he’s more metrics-obsessed than I’d prefer, in general I’ve been a fan of Capers Jones‘s contributions to the software development industry. In his interesting InfoQ article, “Evaluating Agile and Scrum with Other Software Methodologies“, Capers defines, as one of his methodology candidates, possibly the worst software methodology ever conceived:

CMMI 1 with waterfall: The Capability Maturity Model Integrated™ (CMMI) of the Software Engineering Institute is a well-known method for evaluating the sophistication of software development. CMMI 1 is the bottom initial level of the 5 CMMI levels and implies fairly chaotic development. The term “waterfall” refers to traditional software practices of sequential development starting with requirements and not doing the next step until the current step is finished. – Capers Jones

I shouldn’t laugh, but LOL! In the “beginning“, virtually all software projects were managed in accordance with the “Chaos + Waterfall” methodology. Even with all the progress to date, I’d speculate that many projects unwittingly still adhere to it. Gee, I wonder how many of these clunkers are lurching forward under the guise of being promoted as “agile“.

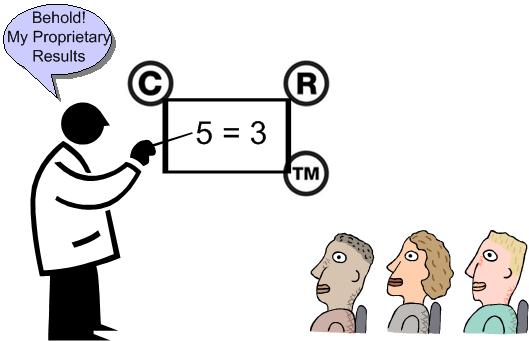

Moving on to the scholarly guts of Mr. Jones’ article, he compares 10 of his personally defined methodologies in terms of several of his personally defined speed, quality, and economic metrics. He also uses his personal, proprietary models/equations/assumptions to calculate apparently objective results for evaluation by executive decision-makers.

I’m not going to discuss or debate the results of Capers’ comparisons because that’s not why I wrote this post. I wrote this post because personally, I don’t think personal and objective mix well together in efforts like these. There’s nothing wrong with smart people generating impressive numeric results that appear objective but are based on hidden/unknown personal assumptions and mental models. However, be leery of any and every numeric result that any expert presents to you.

To delve more deeply into the “expert delusion“, try reading “Proofiness: How You’re Being Fooled by the Numbers” or any of Nassim Taleb‘s books.

One Step Forward, N-1 Steps Back

For the purpose of entertainment, let’s assume that the following 3-component system has been deployed and is humming along providing value to its users:

Next, assume that a 4-sprint enhancement project that brought our enhanced system into being has been completed. During the multi-sprint effort, several features were added to the system:

OK, now that the system has been enhanced, let’s say that we’re kicking back and doing our project post-mortem. Let’s look at two opposite cases: the Ideal Case (IC) and the Worst Case (WC).

First, the IC:

During the IC:

- we “embraced” change during each work-sprint,

- we made mistakes, acknowledged and fixed them in real-time (the intra-sprint feedback loops),

- the work of Sprint X fed seamlessly into Sprint X+1.

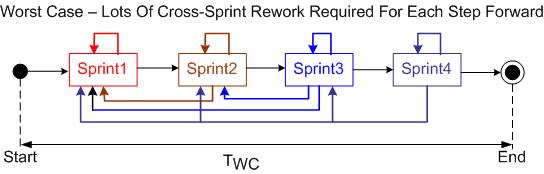

Next, let’s look at what happened during the WC:

Like the IC, during each WC work-sprint:

- we “embraced” change during each work-sprint,

- we made mistakes, acknowledged and fixed them in real-time (the intra and inter-sprint feedback loops),

- the work of Sprint X fed seamlessly into Sprint X+1.

Comparing the IC and WC figures, we see that the latter was characterized by many inter-sprint feedback loops. For each step forward there were N-1 steps backward. Thus, TWC >> TIC and $WC >> $IC.

WTF? Why were there so many inter-sprint feedback loops? Was it because the feature set was ill-defined? Was it because the in-place architecture of the legacy system was too brittle? Was it because of scope creep? Was it because of team-incompetence and/or inexperience? Was it because of management pressure to keep increasing “velocity” – causing the team to cut corners and find out later that they needed to go back often and round those corners off?

So, WTF is the point of this discontinuous, rambling post? I dunno. As always, I like to make up shit as I go.

After-the-fact, I guess the point can be that the same successes or dysfunctions can happen during the execution of an agile project or during the execution of a project executed as a series of “mini-waterfalls“:

- ill-defined requirements/features/user-stories/function-points/use-cases (whatever you want to call them)

- working with a brittle, legacy, BBOM

- team incompetence/inexperience

- scope creep

- schedule pressure

Ultimately, the forces of dysfunction and success are universal. They’re independent of methodology.

The Least Used Option

“We need to estimate how many people we need, how much time, and how much money. Then we’ll know when we’re running late and we can, um, do something.”

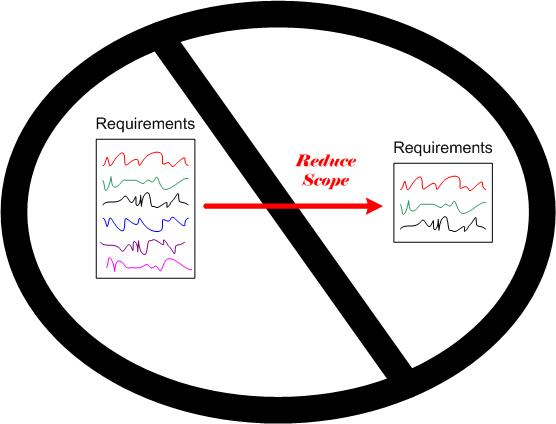

OK, assuming we are indeed running late and, as ever, “schedule is king“. WTF are our options?

- We can add more people.

- We can explicitly or (preferably) implicitly impose mandatory overtime; paid or (preferably) unpaid.

- We can reduce the project scope.

The least used option, because it’s the only one that would put management in an uncomfortable position with the customer(s), is the last one. This, in spite of the fact that it is the best option for the team’s well being over both the short and long term.

Agile Software Factories

Agile Overload

Since I buy a lot of Kindle e-books, Amazon sends me book recommendations all the time. Check out this slew of recently suggested books:

My fave in the list is “Agile In A Flash“. I’d venture that it’s written for the ultra-busy manager on-the-go who can become an agile expert in a few hours if he/she would only buy and read the book. What’s next? Agile Cliff notes?

“Agile” software development has a lot going for it. With its focus on the human-side of development, rapid feedback control loops to remove defects early, and its spirit of intra-team trust, I can think of no better way to develop software-intensive systems. It blows away the old, project-manager-is-king, mechanistic, process-heavy, and untrustful way of “controlling” projects.

However, the word “agile” has become so overloaded (like the word “system“) that….

Everyone is doing agile these days, even those that aren’t – Scott Ambler

Gawd. I’m so fed up with being inundated with “agile” propaganda that I can’t wait for the next big silver bullet to knock it off the throne – as long as the new king isn’t centered around the recently born, fledgling, SEMAT movement.

What about you, dear reader? Do you wish that the software development industry would move on to the next big thingy so we can get giddily excited all over again?