Archive

Dream, Mess, Catastrophe

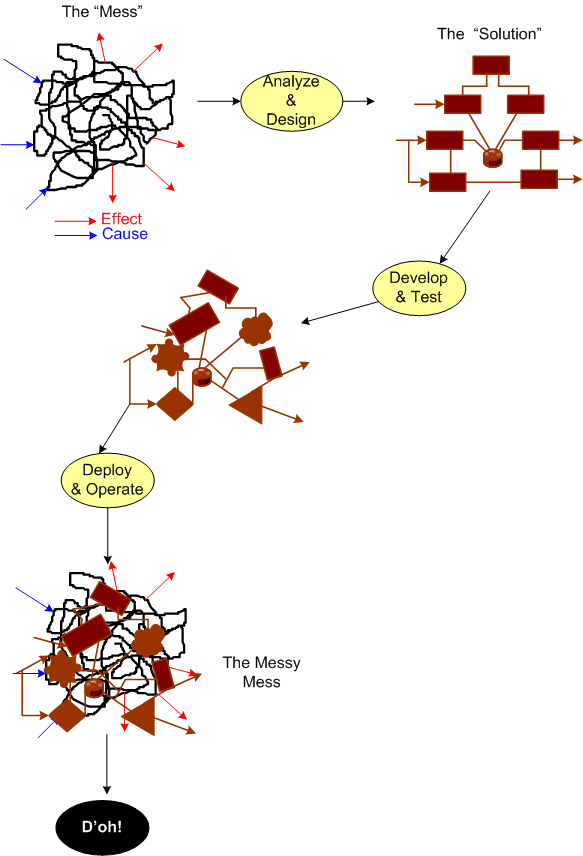

To build high quality, successful, long-lived, “Big” software, you must design it in terms of layers (that’s why the ISO ISO model for network architecture has 7, crisply defined layers). If you don’t leverage the tool of layering (and its close cousin – leveling) in an attempt to manage complexity, then: your baby won’t have much conceptual integrity; you’ll go insane; and you’ll be the unproud owner of a big ball of mud that sucks down maintenance funds like a Dyson and may crumble to pieces at the slightest provocation. D’oh!

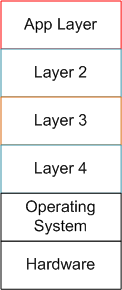

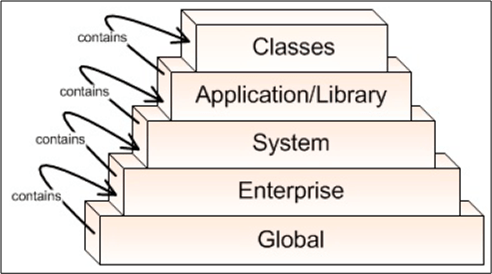

The figure below shows a reference model for a layered application. Note that even though we have a neat stack, we can’t tell if we have a winner on our hands.

By adding the inter-layer dependencies to the reference architecture, the true character of our software system will be revealed:

In the “Maintenance Dream“, the inter-layer APIs are crisply defined and empathetically exposed in the form a well documented interfaces, abstractions, and code examples. The programmer(s) of a given layer only have to know what they have to provide to the users above them and what the next layer below lovingly provides to them. Ah, life is good.

Next, shuffle on over to the “Maintenance Mess“. Here, we have crisply defined layers, but the allocation of functionality to the layers has been hosed up ( a violation of the principle of “leveling“) and there’s a beast in the making. Thus, in order for App Layer programmers to be productive, they have to stuff their head with knowledge/understanding of all the sub-layer APIs to get their jobs done. Hopefully, their heads don’t explode and they don’t run for the exits.

Finally, skip on over to the (shhh!) “Maintenance Catastrophe“. Here, we have both a leveling mess and an incoherent set of incomprehensible (to mere mortals) inter-layer APIs. In the worst case: the layers aren’t discernible from one another; it takes “forever” to on-board new project members; it takes forever to fix bugs; it takes forever to add features; and it takes an heroic effort to keep the abomination alive and kicking. Double D’oh!

Forever == Lots Of Cash

In orgs that have only ever created “Maintenance Messes and Catastrophies“, since they’ve never experienced a “Maintenance Dream“, they think that high maintenance costs, busted schedules, and buggy releases are the norm. How do you explain the color green to someone who’s spent his/her whole life immersed in a world of red?

World Class Help

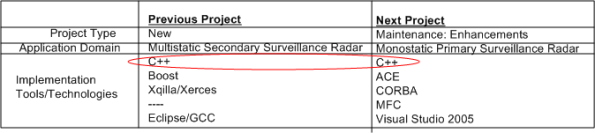

I’m currently transitioning from one software project to another. After two years of working on a product from the ground up, I will be adding enhancements to a legacy system for an existing customer.

The table below shows the software technologies embedded within each of the products. Note that the only common attribute in the table is C++, which, thank god, I’m very proficient at. Since ACE, CORBA, and MFC have big, complicated, “funky” APIs with steep learning curves, it’s a good thing that “training” time is covered in the schedule as required by our people-centric process. 🙂

I’m not too thrilled or motivated at having to spin up and learn ACE and CORBA, which (IMHO) have had their 15 minutes of fame and have faded into history, but hey, all businesses require maintenance of old technologies until product replacement or retirement.

I am, however, delighted to have limited e-access to LinkedIn connection Steve Vinoski. Steve is a world class expert in CORBA know-how who’s co-authored (with Michi Henning) the most popular C++ CORBA programming book on the planet:

Even though Steve has moved on (C++ -> Erlang, CORBA -> REST), he’s been gracious enough to answer some basic beginner CORBA questions from me without requiring a consulting contract 🙂 Thanks for your generosity Steve!

Messy Mess

Human And Automated Controllers

Note: The figures that follow were adapted from Nancy Leveson‘s “Engineering A Safer World“.

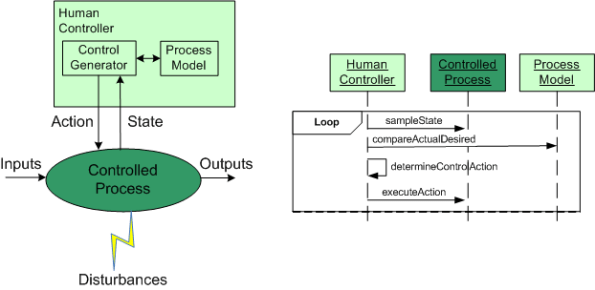

In the good ole days, before the integration of fast (but dumbass) computers into controlled-process systems, humans had no choice but to exercise direct control over processes that produced some kind of needed/wanted results. During operation, one or more human controllers would keep the “controlled process” on track via the following monitor-decide-execute cycle:

- monitor the values of key state variables (via gauges, meters, speakers, etc)

- decide what actions, if any, to take to maintain the system in a productive state

- execute those actions (open/close valves, turn cranks, press buttons, flip switches, etc)

As the figure below shows, in order to generate effective control actions, the human controller had to maintain an understanding of the process goals and operation in a mental model stored in his/her head.

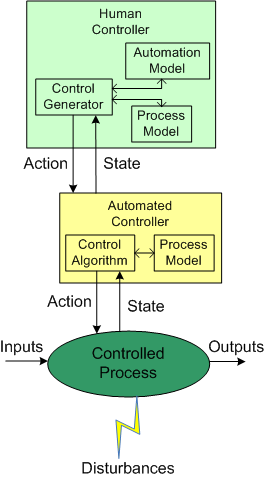

With the advent of computers, the complexity of systems that could be, were, and continue to be built has skyrocketed. Because of the rise in the cognitive burden imposed on humans to effectively control these newfangled systems, computers were inserted into the control loop to: (supposedly) reduce cognitive demands on the human controller, increase the speed of taking action, and reduce errors in control judgment.

The figure below shows the insertion of a computer into the control loop. Notice that the human is now one step removed from the value producing process.

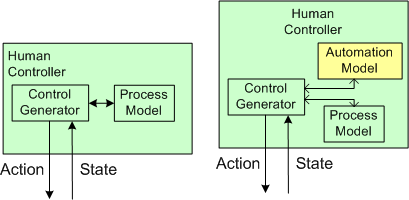

Also note that the human overseer must now cognitively maintain two mental models of operation in his/her head: one for the physical process and one for the (supposedly) subservient automated controller:

Assuming that the automated controller unburdens the human controller from many mundane and high speed monitoring/control functions, then the reduction in overall complexity of the human’s mental process model may more than offset the addition of the requirement to maintain and understand the second mental model of how the automated controller works.

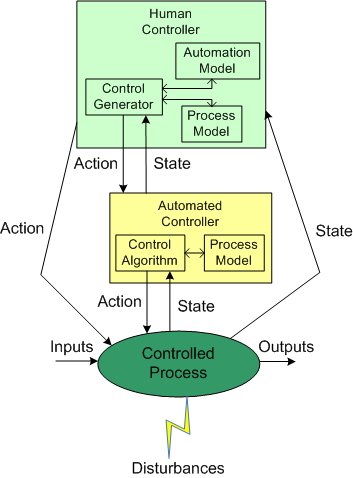

Since computers are nothing more than fast idiots with fixed control algorithms designed by fallible human experts (who nonetheless often think they’re infallible in their domain), they can’t issue effective control actions in disturbance situations that were unforeseen during design. Also, due to design flaws in the hardware or software, automated controllers may present an inaccurate picture of the process state, or fail outright while the controlled process keeps merrily chugging along producing results.

To compensate for these potentially dangerous shortfalls, the safest system designs provide backup state monitoring sensors and control actuators that give the human controller the option to override the “fast idiot“. The human controller relies primarily on the interface provided by the computer for monitoring/control, and secondarily on the direct interface couplings to the process.

Well Architected

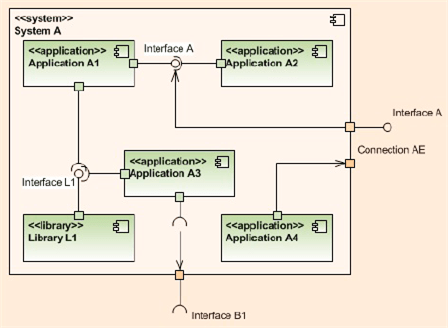

The UML component diagram below attempts to model the concept and characteristics of a well architected software-intensive system.

What other attributes of well architected/designed systems are there?

Without a sketched out blueprint like this, if you start designing and/or coding and cobbling together components randomly selected out of the blue and with no concept of layering/balancing, the chance that you end up will a well architected system is nil. You may get it “working” and have a nice GUI pasted on top of the beast, but under the covers it will be fragile and costly to extend/maintain/debug – unless a miracle has occurred.

If you or your management don’t know or care or are “allowed” to expose, capture, and continuously iterate on that architecture/design dwelling in your faulty and severely limited mind and memory, then you deserve what you get. Sadly, even though they don’t deserve it, every other stakeholder gets it too: your company, your customers, your fellow downstream maintainers, etc….

Graphics, Text, And Source Code

On the left, we have words of wisdom from Grady Booch and friends. On the right, we have sage advice hatched from the “gang of four“. So, who’s right?

Why, both groups are “right“. If all you care about is “recording the design in source code“, then you’re “wrong“…

If you’re a software “anything” (e.g. architect, engineer, lead, manager, developer, programmer, analyst) and you haven’t read these two classics, then either read them or contemplate seeking out a new career.

But wait! All may not be lost. If you think object orientation is obsolete and functional programming is the way of the future, then forget (almost) everything that was presented in this post.

An Epoch Mistake

Let’s start this hypothetical story off with some framing assumptions:

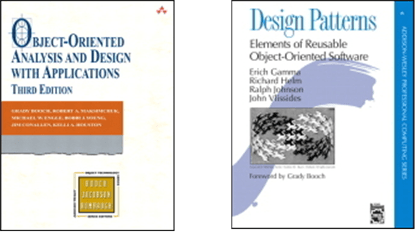

Assume (for a mysterious historical reason nobody knows or cares to explore) that timestamps in a legacy system are always measured in “seconds relative to midnight” instead of “seconds relative to the unix epoch of 1/1/1970“.

Assume that the system computes many time differences at a six figure Hz rate during operation to fulfill it’s mission. Because “seconds relative to midnight” rolls over from 86399 to 0 every 24 hours, the time difference logic has to detect (via a disruptive “if” statement) and compensate for this rollover; lest its output is logically “wrong” once a day.

Assume that the “seconds relative to the unix epoch of 1/1/1970” library (e.g. Boost.Date_Time) satisfies the system’s dynamic range and precision requirements.

Assume that the design of a next generation system is underway and all the time fields in the messages exchanged between the system components are still mysteriously specified as “seconds since midnight” – even though it’s known that the added CPU cycles and annoyance of rollover checking could be avoided with a stroke of the pen.

Assume that the component developers, knowing that they can dispense with the silly rollover checking:

- convert each incoming time field into “seconds since the unix epoch“,

- use the converted values to perform their internal time difference computations without having to check/compensate for midnight rollover,

- convert back to “seconds since midnight” on output as required.

Assume that you know what the next two logical steps are: 1) change the specification of all the time fields in the messages exchanged between the system components from the midnight reference origin to the unix epoch origin, 2) remove the unessential input/output conversions:

Suffice it to say, in orgs where the culture forbids the admittance of mistakes (which implicates most orgs?) because the mistake-maker(s) may “look fallible“, next steps like this are rarely taken. That’s one of the reasons why old product warts are propagated forward and new warts are allowed to sprout up in next generation products.

Levels, Components, Relationships

In the Crosstalk Journal, Michael Tarullo has written a nice little article on documenting software architectures. Using the concept of abstract levels (a necessary, but not sufficient tool, for understanding complex systems) and one UML component diagram per level, he presents a lightweight process for capturing big software system architecture decisions out of the ether.

Levels Of Abstraction

Mr. Tarullo’s 5 levels of abstraction are shown below (minor nit: BD00 would have flipped the figure upside down and shown the most abstract level (“Global“) at the top.

Components Within A Level

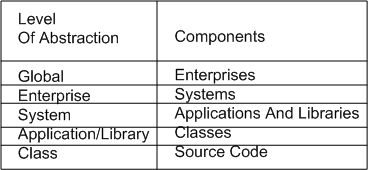

Since “architecture” focuses on the components of a system and the relationships between them, Michael defines the components of concern within each of his levels as:

(minor nit: because the word “system” is too generic and overused, BD00 would have chosen something like “function” or “service” for the third level instead).

Relationships

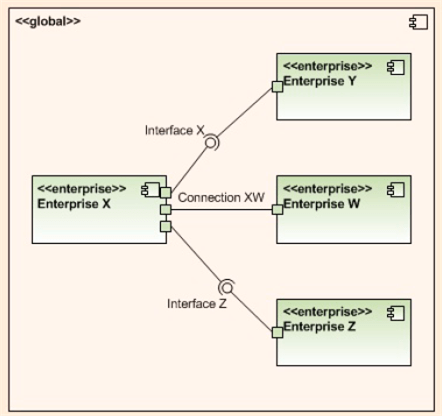

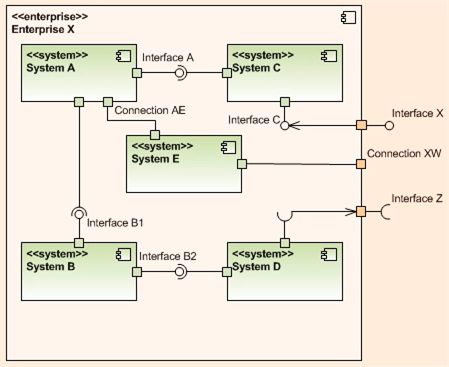

Within a given level of abstraction, Mr. Tarullo uses a UML component diagram with ports and ball/socket pairs to model connections, interfaces (provides/requires), and to bind the components together. He also maintains vertical system integrity by connecting adjacent levels together via ports/balls/sockets.

The three UML component diagrams below, one for each of the top, err bottom, three levels of abstraction in his taxonomy, nicely illustrate his lightweight levels plus UML component diagram approach to software architecture capture.

But what about the next 2 levels in the 5 level hierarchy: the Application/Library and Classes levels of the architecture? Mr. Tarullo doesn’t provide documentation examples for those, but it follows that UML class and sequence diagrams can be used for the Application/Library level, while activity diagrams and state machine diagrams can be good choices for the atomic class level.

Providing and vigilantly maintaining a minimal, lightweight stack of UML “blueprint” diagrams like these (supplemented by minimal “hole-filling” text) seems like a lower cost and more effective way to maintain system integrity, visibility, and exposure to critical scrutiny than generating a boatload of DOD template mandated write-once-read-never text documents, no?

Alas, if:

- you and your borg don’t know or care to know UML,

- you and your borg don’t understand or care to understand how to apply the complexity and ambiguity busting concepts of “layering and balancing“,

- your “official” borg process requires the generation of write-once-read-never, War And Peace sized textbook monstrosities,

then you, your product, your customers, and your borg are hosed and destined for an expensive, conflict filled future. (D’oh! I hate when that happens.)

Persistent Discomfort

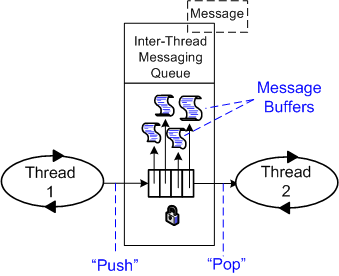

As part of the infrastructure of the distributed, multi-process, multi-threaded system that my team is developing, a parameterized, mutex protected, inter-thread message queue class has been written and dropped into a general purpose library. To unburden application component developers from having to do it, the library-based queue class manages a reusable pool of message buffers that functionally “flow” from one thread to the next.

On the “push” side of the queue, usage is as follows:

- Thread acquires a handle to the next empty Message buffer

- Thread fills Message buffer

- Thread returns handle to the queue (push)

On the “pop” side of the queue, usage is as follows:

- Thread acquires a handle to the next full Message buffer (pop)

- Thread processes the Message content

- Thread returns handle to the queue

So far, so good, right? I thought so too – at the beginning of the project. But as I’ve moved forward during the development of my application component, I’ve been experiencing a growing and persistent discomfort. D’oh!

Using the figure below, I’m gonna share the cause of my “inner thread” discomfort with you.

In order to functionally process an input message and propagate it forward, the inner thread must do the following work:

- Acquire a handle to the next input Message buffer from queue 1 (pop)

- Acquire a handle to the next empty output Message buffer from queue 2

- Utilize the content of the Message from queue 1 to compute/fill in the Message to queue 2

- Return the handle of the input message to queue 1

- Return the handle of the output message to queue 2 (push)

For small messages and/or when the messages are of different types, I don’t see much wrong with this inter-thread message passing approach. However, when the messages are big and of the same type, my discomfort surfaces. In this case (as we shall see), the “utilize” bullet amounts to an unnecessary copy. The more “inner” threads there are in the pipeline, the more performance degradation there is from unnecessary copies.

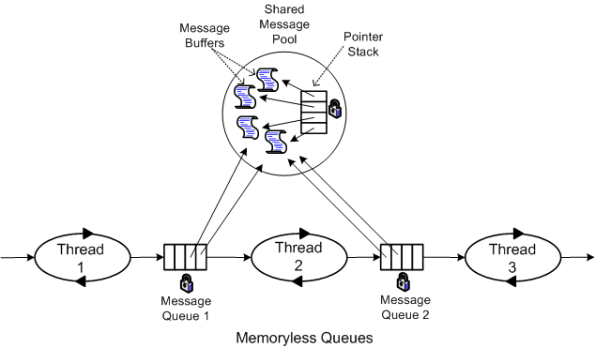

So, how can the copies be eliminated and system performance increased? One way, as the figure below shows, is to move message buffer management responsibility out of the local queue class and into a global, shared message pool class.

In this memory-less queue design, the two pipeline end point threads explicitly assume the responsibility of acquiring and releasing the Message buffer handles from the mutex protected, shared message pool. The first thread “acquires” and the last thread “releases” message buffer handles. Each inner thread, i, in the pipeline performs the following work:

- Pop the handle to the next input Message buffer from queue i-1

- Process the message

- Push the Message buffer handle to queue i

The key to avoiding unessential inner thread copies is that the messages must be intentionally designed to be of the same type.

As soon as I get some schedule breathing room (which may be never), I’m gonna refactor my application infrastructure design and rewrite the code to implement the memoryless queue + global message pool approach. That is, unless someone points out a fatal flaw in my reasoning and/or presents a superior inter-thread message communication pattern.

Design Disclosure

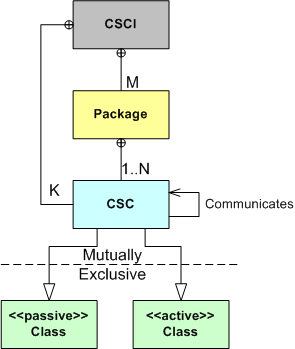

Recently, I had to publicly disclose the design of the multi-threaded CSCI (Computer Software Configuration Item) that I’m currently bringing to life with a small group of colleagues. The figure below shows the entities (packages, CSCs (Computer Software Components), Classes) and the inter-entity relationship schema that I used to create the CSCI design artifacts.

As the figure illustrates, the emerging CSCI contains M packages and K top level CSCs . Each package contains from 1 to N 2nd level CSCs that associate with each other via the “communicates” (via messages) relationship. Each CSC is of the “passive” or “active” class type, where “active” means that the CSC executes within its own thread of control.

Using the schema, I presented the structural and behavioral aspects of the design as a set of views:

- The threads view (behavioral )

- The packages view (structural)

- The class diagrams view (structural)

- The sequence diagrams view (behavioral)

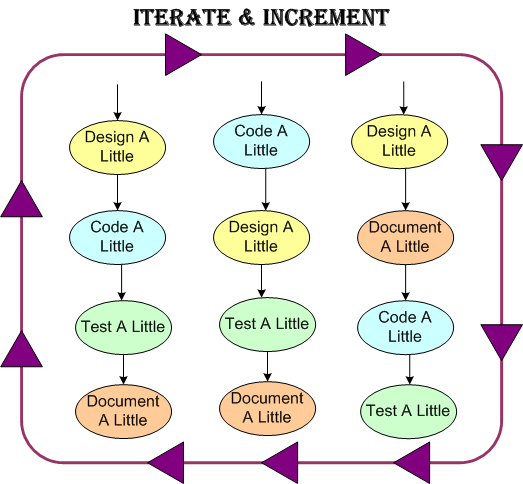

Like any “real” design effort (and unlike the standard sequential design-code-test mindset of “authorities“), I covertly used the incremental and iterative PAYGO methodology (design-a-little, code-a-little, test-a-little, document-a-little) in various mini sequences that, shhhh – don’t tell any rational thinker, just “felt right” in the moment.

As we speak, the effort is still underway and, of course, the software is 90% done. Whoo Hoo! Only 10 more percent to go.