Archive

Properties Of Interest

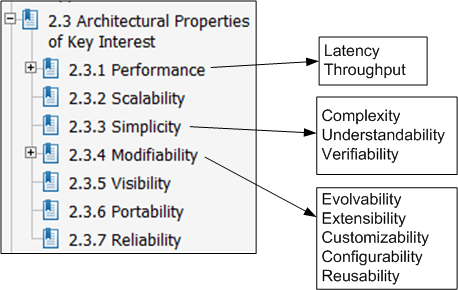

Roy Fielding‘s famous PhD thesis, “Architectural Styles and the Design of Network-based Software Architectures” introduces the REST (REpresentational State Transfer) architectural style for large-scale, distributed, hypermedia-based network applications.

In his thesis, Mr. Fielding defines the non-functional property set that he uses to evaluate various architectural styles against one another:

Of course, there is no universal set of “ilities” definitions that technical stakeholders use to reason about, and evaluate, software architectures. Plus, depending on the application domain one is immersed in, some “ilities” are more important than others. Nevertheless, Mr. Fielding’s set is as good as any other that I’ve seen to date.

Of course, there is no universal set of “ilities” definitions that technical stakeholders use to reason about, and evaluate, software architectures. Plus, depending on the application domain one is immersed in, some “ilities” are more important than others. Nevertheless, Mr. Fielding’s set is as good as any other that I’ve seen to date.

Whenever I see someone’s personal list of “ilities“, sometimes I discover at least one that I’ve never seen before. In Mr. Fielding’s list, the “visibility” property is one such “ility“. Here’s Mr. Fielding’s definition:

Visibility… refers to the ability of a component to monitor or mediate the interaction between two other components.

In a “distributed hypermedia systems” application like the www, visibility impacts several other properties as follows:

Visibility can enable improved performance via shared caching of interactions, scalability through layered services, reliability through reflective monitoring,

and security by allowing the interactions to be inspected by mediators (e.g., network firewalls).

I wonder what my next “ility” discovery will be?

Complicated != Complex

For the non-geeks reading this post, the “!=” symbol is the C++ programming language token for “not equal“.

It seems like a lot of people think that classifying something as “complex” is the same as calling it “complicated“, and vice-versa. That conclusion can be, and often is, true, but it can also be false. I associate “complicated” with “not-understandable” – except to a select few experts. I think of “complex” to be the equivalent of something like “intricately elegant” and understandable to far more people than just experts.

Let’s take an example to illuminate my viewpoint. Assume that the black box system below functions delightfully. It’s reliable, responsive, easy to learn, and does what its users want without frustrating them in the slightest.

Now, in terms of complicated and complex, consider what the system may look like under the covers:

Now, in terms of complicated and complex, consider what the system may look like under the covers:

Of course, most users don’t give a shite what goes on under the covers, but the designing org and its people better well know what does – unless they luckily don’t have any competition to deal with, and hence, have their customers in a vice grip.

You see, at some point in time, the users will want improvements to the system as their needs evolve. If the original team of builders of implementation #1 are the only people who know the (so-called) design well enough to change it without breaking any existing capabilities, then the development org is hosed if those people leave. In effect, the org is held hostage by a small cadre of people. D’oh!

In the complex-complex implementation on the far right, even if the original builders leave the development org, the (relatively) elegant and well thought out design structure facilitates easy on-boarding of replacement builders. As an added bonus, the effort needed to add features and enhancements to the product is way less costly and risky than the other jaggedly complicated implementations.

So, given the portfolio of products in your org, how would you assess them in terms of the complexity and complicated attributes? If, and it’s probably a big IF, you could publicly communicate your assessment without fear of marginalization, or worse, how many people in your org do you think would publicly agree with your assessment? Uh, how abut privately? Would the number of public “agreers” match the number of private “agreers“?

Centralized, Federated, Decentralized

1 Prelude

A colleague on LinkedIn.com pointed me toward this Doug Schmidt, et al, paper: “Evaluating Technologies for Tactical Information Management in Net-Centric Systems“. In it, Doug and crew qualitatively (scalability, availability, configurability) and quantitatively (latency, jitter) evaluate three different architectural implementations of the Object Management Group‘s (OMG) Data Distribution Service (DDS): centralized, federated, and decentralized.

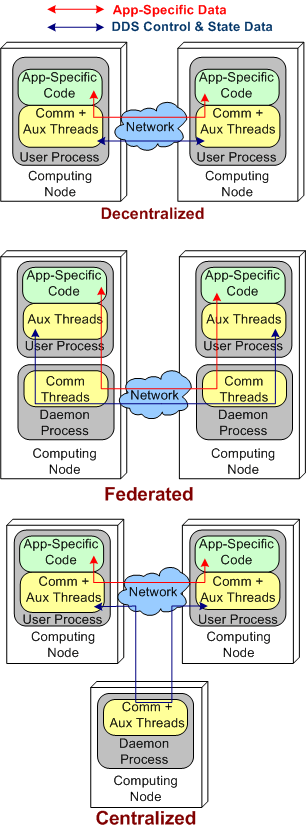

The stacked trio of figures below model the three DDS architecture types. They’re slightly enhanced renderings of the sketches in the paper.

2 Quantitative Comparisons

DDS was specifically designed to meet the demanding latency and jitter (the standard deviation of latency) performance attributes that are characteristic of streaming, Distributed Real-Time Event (DRE) systems like defense and air traffic control radars. Unlike most client-server, request-response systems, if data required for human or computer decision-making is not made available in a timely fashion, people could die. It’s as simple and potentially horrible as that.

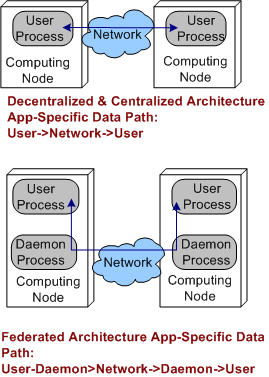

Applying the systems thinking idiom of “purposeful, selective ignorance“, the pics below abstract away the unimportant details of the pics above so that the architecture types can be compared in terms of latency and jitter performance.

By inspecting the figures, it’s a no brainer, right? The steady-state latency and jitter performance of the decentralized and centralized architectures should exceed that of the federated architecture. There is no “middleman“, a daemon, for application layer data messages to pass through.

Sure enough, on their two node test fixture (I don’t know why they even bothered with the one node fixture since that really isn’t a “distributed” system in my mind) , the Schmidt et al measurements indicate that the latency/jitter performance of the decentralized and centralized architectures exceed that of the federated architecture. The performance difference that they measured was on the order of 2X.

3 Qualitative Comparisons

In all distributed systems, both DRE and Client-Server types, achieving high operational availability is a huge challenge. Hell, when the system goes bust, fuggedaboud the timeliness of the data, no freakin’ work can get done and panic can and usually does set in. D’oh!

With that scary aspect in mind, let’s look at each of the three architectures in terms of their ability to withstand faults.

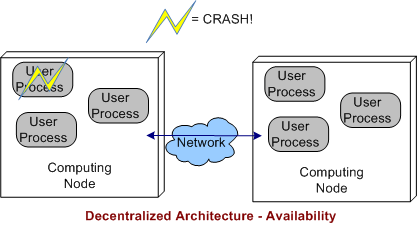

3.1 Decentralized Architecture Availability

In a decentralized architecture, there are no invasive daemons that “leak” into the application plane so we can’t talk about daemon crashes. Thus, right off the bat we can “arguably” say that a decentralized architecture is more resistant to faults than the federated or centralized architectures.

As the picture below shows, when a user application layer process dies, the others can continue to communicate with each other. Depending on what the specific application is required to do during operation, at least some work may be able to still get accomplished even though one or more app components go kaput.

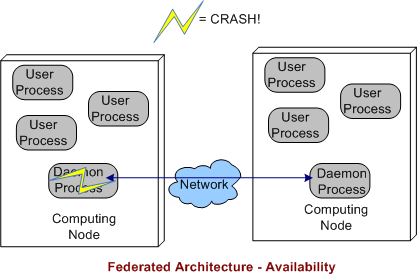

3.2 Federated Architecture Availability

In a federated architecture, when a daemon process dies, a whole node and all the subscriber application user processes running on it are severed from communicating with the user processes running on the other nodes (see the sketch below) in the system. Thus, the federated architecture is “arguably” less fault tolerant than the decentralized and (as we’ll see) centralized architectures. However, through judicious “allocation” of user processes to nodes (the fewer the better – which sort of defeats the purpose of choosing a federation for per node intra-communication performance optimization), some work still may be able to get accomplished when a node’s daemon crashes.

If the node daemons stay viable but a user application dies, then the behavior of a federated architecture, DDS-based system is the same as that of a decentralized architecture

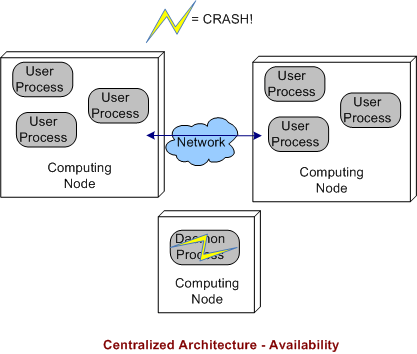

3.3 Centralized Architecture Availability

Finally, we come to the robustness of a centralized DDS architecture. As shown below, since the single daemon overlord in the system is not (or should not be) involved in inter-process application layer data communications, if it crashes, then the system can continue to do its full workload. When a user process crashes instead of, or in addition to, the daemon, then the system’s behavior is the same as a decentralized architecture.

4 BD00 Commentary

Because he works on data streaming DRE radar systems, Jimmy likes, I mean BD00 likes, the DDS pub-sub architectural style over broker-based, distributed communication technologies like C/S CORBA and JMS queues. It should be obvious that the latter technologies are not a good match for high availability and low latency DRE applications. Thus, trying to jam fit a new DRE application into a CORBA or JMS communication platform “just because we have one” is a dumb-ass thing to do and is sure to lead to high downstream maintenance costs and a quicker route to archeosclerosis.

Within the DDS space, BD00 prefers the decentralized architecture over the federated and centralized styles because of the semi-objective conclusions arrived at and documented in this post.

SysML, UML, MML

I really like the SysML and UML for modeling and reasoning about complex, multi-technology and software-centric systems respectively, but I think they have one glaring shortcoming. They aren’t very good at modeling distributed, multi-process, multi-threaded systems. Why? Because every major element (except for a use case?) is represented as a rectangle. As far as I know, a process can be modeled as either a parallelogram or a stereotyped rectangular UML class (SysML block ):

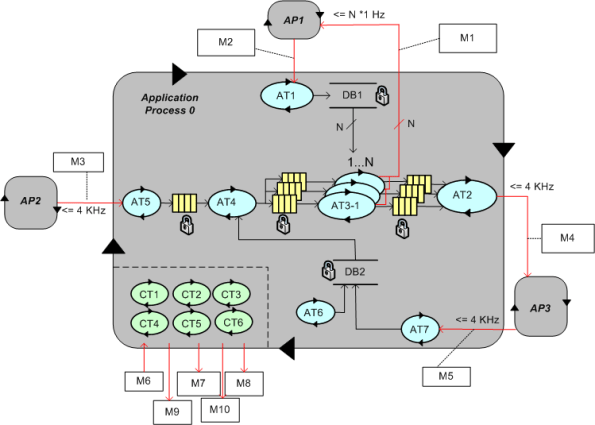

To better communicate an understanding of multi-threaded, multi-process systems, I’ve created my own graphical “proprietary” (a.k.a. homegrown) symbology. I call it the MML (UML profile). Here is the MML symbol set.

An example MML diagram of a design that I’m working on is shown below. The app-specific modeling element names have been given un-descriptive names like ATx, APx, DBx, Mx for obvious reasons.

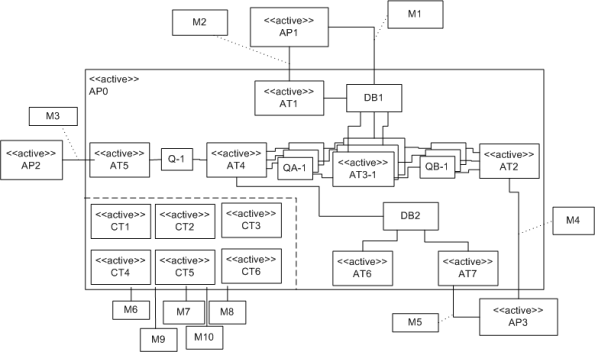

Compare this model with the equivalent rectangular UML diagram below. I purposely didn’t use color and made sure it was bland so that you’d answer the following question the way I want you to. Which do you think is more expressive and makes for a better communication and reasoning tool?

If you said “the UML diagram is better“, that’s OK. 🙂

A Role Model For Change

In the comments section of the Horse And Buggy post, Steve Vinoski was gracious enough to provide links to four IEEE Computer Society columns that he wrote a few years ago on the topic of distributed software systems. For your viewing pleasure, I’ve re-listed them here:

http://steve.vinoski.net/pdf/IEEE-Serendipitous Reuse.pdf

http://steve.vinoski.net/pdf/IEEE-Demystifying_RESTful_Data_Coupling.pdf

http://steve.vinoski.net/pdf/IEEE-Convenience_Over_Correctness.pdf

http://steve.vinoski.net/pdf/IEEE-RPC_and_REST_Dilemma_Disruption_and_Displacement.pdf

Of course, being a Vinoski fan, I read them all. If you choose to read them, and you’re not an RPC (Remote Procedure Call) zealot, I think you’ll enjoy them as much as I did. To view and learn more about distributed software system design from a bunch of Steve Vinoski video interviews, check out the collection of them at InfoQ.com.

I really admire Steve because he made a major leap out of his comfort zone into a brave new world. He transitioned from being a top notch CORBA and C++ proponent to being a REST and Erlang advocate. I think what he did is admirable because it’s tough, especially as one gets older, to radically switch mindsets after investing a lot of time acquiring deep expertise in any technical arena (the tendency is to dig one’s heels in). Add to that the fact that he worked for big gun CORBA vendor Iona Technologies (which no longer exists as an independent company) during the time of his epiphany, and you’ve got a bona fide role model for change, no?

No Man’s Land

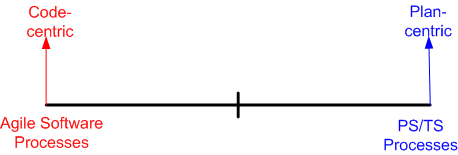

Having recently just read my umpteenth Watts Humphrey book on his PSP/TSP (Personal Software Process/Team Software Process) methodology, I find myself struggling, yet again, to reconcile his right wing thinking with the left wing “Agile” software methodologies that have sprouted up over the last 10 years as a backlash against waterfall-like methodologies. This diagram models the situational tension in my hollow head:

It’s not hard to deduce that prescriptive, plan-centric processes are favored by managers (at least those who understand the business of software) and demonstrative, code-centric processes are favored by developers. Duh!

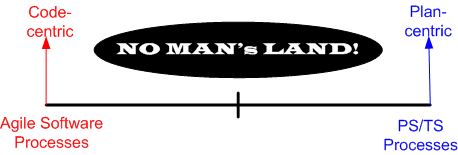

Advocates of both the right and the left have documented ample evidence that their approach is successful, but neither side (unsurprisingly) willingly publicizes their failures much. When the subject of failure is surfaced, both sides always attribute messes to bad “implementations” – which of course is true. IMHO, given a crack team of developers, project managers, testers, and financial sponsors, ANY disciplined methodology can be successful – those on the left, those on the right, or those toiling in NO MAN’s LAND.

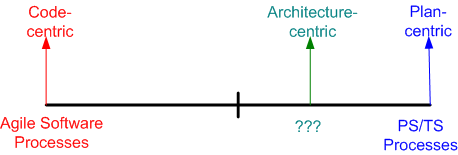

l’ve been the anointed software “lead” on two, < 10 person, software teams in the past. Both as a lead and an induhvidual contributor, the approach I’ve always intuitively taken toward software development can be classified as falling into “no man’s land“. It’s basically an informal, but well-known, Brooksian, architecture-centric, strategy that I’d characterize as slightly right-leaning:

As far as I know, there’s no funky, consensus-backed, label like “semi-agile” or “lean planning” to capture the essence of architecture-centric development. There certainly aren’t any “certification” training courses or famous promoters of the approach. This book, which I discovered and read after I’d been designing/developing in this mundane way for years, sort of covers the process that I repeatedly use.

In my tortured mind (and you definitely don’t want to go there!), architecture-centricity simply means “centered on high level blueprints“. Early on, before the horses are let out of the barn and massive, fragmented, project effort starts churning under continuous pressure from management for “status“, a frantic iterative/sketching/bounding/synthesis activity takes place. With a visible “rev X” architecture in hand (one that enumerates the structural elements, their connectivity, and the macro behavior that the system must manifest) for guidance, people can then be assigned to the sparsely defined, but bounded, system elements so that they can create reasonable “Rev 0” estimates and plans. The keys are that only one or two or three people record the lay of the land. Subsequently, the element assignees produce their own “Rev 0” estimates – prior to igniting the frenetic project activity that is sure to follow.

In a nutshell, what I just described is the front-end of the architecture-centric approach as I practice it; either overtly or covertly. The subsequent construction activities that take place after a reasonably solid, lightweight, “rev X”, architecture (or equivalent design artifact for smaller scale projects) has been recorded and disseminated are just details. Of course, I’m just joking in that last sentence, but unless the macro front end is secured and repeatedly used as the “go to bible” shortly after T==start, all is lost – regardless of the micro-detailed practices (TDD, automated unit tests, continuous integration, continuous delivery, yada yada yada) that will follow. But hey, the content of this post is just Bulldozer00’s uncredentialed and non-expert opinion, so don’t believe a word of it.

Movin’ On Up

For some unknown reason, I recently found myself reflecting back on how I’ve progressed as a software engineer over the years. After being semi-patient and allowing the fragmented thoughts to congeal, I neatly summed up the quagmire as thus:

- Single Node – Single Process – Single Threaded (SST) programming

- Single Node – Single Process – Multi-Threaded (SSM) programming

- Single Node – Multi-Process – Multi-Threaded (SMM) programming

- Multi-Node – Multi-Process – Multi-Threaded (MMM) programming

It’s interesting to note that my progression “up the stack” of abstraction and complexity did not come about from the execution of some pre-planned, grand master strategy . I feel that I was “tugged” by some unknown force into pursuing the knowledge and skills that have gotten me to a semi-proficient state of expertise in the design and programming of MMM systems.

Being a graphical type of dude, here’s a pictorial representation of how I “moved on up“.

How about you? Do you have a master plan for movin’ on up? Wherever you are in relation to this concocted stack, are you content to stay there – in the womb so-to-speak? If you want to adopt something like it as a roadmap for professional development, are you currently immersed in the type of environment that would allow you to do so?

Push And Pull Message Retrieval

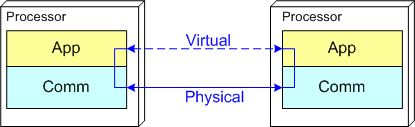

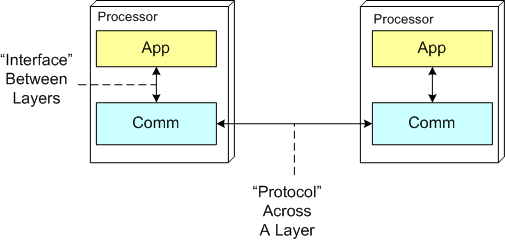

The figure below models a two layer distributed system. Information is exchanged between application components residing on different processor nodes via a cleanly separated, underlying communication “layer“. App-to-App communication takes place “virtually“, with the arcane, physical, over-the-wire, details being handled under the covers by the unheralded Comm layer.

In the ISO OSI reference model for inter-machine communication, the vertical linkage between two layers in a software stack is referred to as an “interface” and the horizontal linkage between two instances of a layer running on different machines is called a “protocol“. This interface/protocol distinction is important because solving flow-control and error-control issues between machines is much more involved than handling them within the sheltered confines of a single machine.

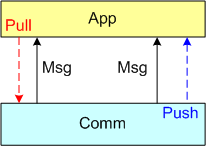

In this post, I’m going to focus on the receiving end of a peer-to-peer information transfer. Specifically, I’m going to explore the two methods in which an App component can retrieve messages from the comm layer: Pull and Push. In the “Pull” approach, message transfer from the Comm layer to the App layer is initiated and controlled by the App component via polling. In the “Push” method, inversion of control is employed and the Comm layer initiates/controls the transfer by invoking a callback function installed by the App component on initialization. Any professional Comm subsystem worth its salt will make both methods of retrieval available to App component developers.

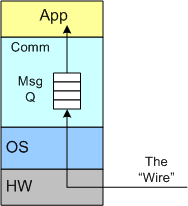

The figure below shows a model of a comm subsystem that supplies a message queue between the application layer and the “wire“. The purpose of this queue is to prevent high rate, bursty, asynchronous message senders from temporarily overwhelming slow receivers. By serving as a flow rate smoother, the queue gives a receiver App component a finite amount of time to “catch up” with bursts of messages. Without this temporary holding tank, or if the queue is not deep enough to accommodate the worst case burst size, some messages will be “dropped on the floor“. Of course, if the average send rate is greater than the average processing rate in the receiving App, messages will be consistently lost when the queue eventually overflows from the rate mismatch – bummer.

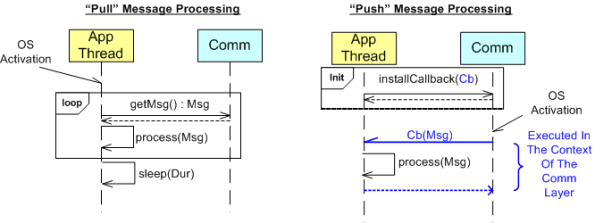

The UML sequence diagram below zeroes in on the interactions between an App component thread of execution and the Comm layer for both the “Push” and “Pull” methods of message retrieval. When the “Pull” approach is implemented, the OS periodically activates the App thread. On each activation, the App sucks the Comm layer queue dry; performing application-specific processing on each message as it is pulled out of the Comm layer. A nice feature of the “Pull” method, which the “Push” method doesn’t provide, is that the polling rate can be tuned via the sleep “Dur(ation)” parameter. For low data rate message streams, “Dur” can be set to a long time between polls so that the CPU can be voluntarily yielded for other processing tasks. Of course, the trade-off for long poll times is increased latency – the time from when a message becomes available within the Comm layer to the time it is actually pulled into the App layer.

In the”Push” method of message retrieval, during runtime the Comm layer activates the App thread by invoking the previously installed App callback function, Cb(Msg), for each newly received message. Since the App’s process(Msg) method executes in the context of a Comm layer thread, it can bog down the comm subsystem and cause it to miss high rate messages coming in over the wire if it takes too long to execute. On the other hand, the “Push” method can be more responsive (lower latency) than the “Pull” method if the polling “Dur” is set to a long time between polls.

So, which method is “better“? Of course, it depends on what the Application is required to do, but I lean toward the “Pull” Method in high rate streaming sensor applications for these reasons:

- In applications like sensor stream processing that require a lot of number crunching and/or data associations to be performed on each incoming message, the fact that the App-specific processing logic is performed within the context of the App thread in the “Pull” method (instead of the Comm layer) means that the Comm layer performance is not dependent on the App-specific performance. The layers are more loosely coupled.

- The “Pull” approach is simpler to code up.

- The “Pull” approach is tunable via the sleep “Dur” parameter.

How about you? Which do you prefer, and why?

Mismatch

Assume that you’re tasked to create a two component, distributed software system as shown in the figure below. The nature of the application is such that during runtime, component 1 will continuously transmit a “bursty“, asynchronous stream of messages to component 2. During evolution of the system in the future, you know that more and more stages will be tacked on to the “pipeline“, with each stage adding value to a growing customer base (if you don’t screw it up and hatch a BBoM).

Note that the relationship between application components is peer-to-peer and not client-server like this:

One question is this: “Why on earth would anyone choose a client-server messaging system (with peer-to-peer capability tacked on) over a peer-to-peer messaging system for this class of application?“. The question especially applies to product organizations that strive to develop distinctly elegant and innovative solutions – which hopefully includes yours. A second question is: “What would technologically savvy customers think?“. Of course, if you think your customers are dumb-asses (and you won’t be in business for long if you do) and can’t tell the difference, then the situation is a “don’t care“, no?

Flouting Convention

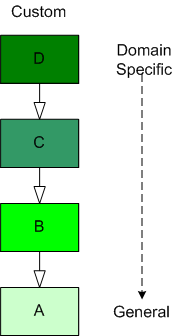

As software-centric systems get more complex, one of the most effective tools for preventing the creation of monstrous BBoMs downstream is “layering”. The figure below shows a generic model of the layering concept.

When you use layering, you partition your system into a vertical stack with the most “exciting” application-specific functions and objects at the top of the stack and the more mundane and boring functionality down in the basement. In a pure layered system, the higher layers depend on the services provided by the lower levels and there are no dependencies the other way. The cleaner and crisper your inter-layer boundaries, the lower your maintenance cost and frustration.

The figure below shows the conventional approach of representing an inheritance hierarchy in an object oriented design. What’s wrong with this picture? Relative to the layered model, it’s “upside down“. The most general class is on top and the most domain-specific class is at the bottom. WTF and D’oh!

Since “layering” has been around much longer than object-orientation, Bulldozer00 thinks that a layered, object-oriented software system should always be presented to stakeholders like this:

This method of representation aligns cleanly with the layered “view” of the system and is thus, less confusing and dis-orienting to all audiences, dontcha think? To hell with convention, – at least in this situation.