Archive

The Magical Number 30

In agile processes, especially Scrum, 30 is a magical number. A working product increment should never take more than 30 days to produce. The reasoning, which is sound, is that you’ll know exactly what state the evolving product is in quicker than you normally would under a “traditional” process. You can then decide what to do next before expending more resources.

The trouble I have with this 30 day “law” is that not all requirements/user-stories/function-points/”shalls” are created equal. Getting from a requirement to tested, reviewed, integrated, working code may take much longer – especially for big, distributed systems or algorithmically dense components.

Arbitrarily capping delivery dates to a maximum of 30 days and mandating deliveries to be rigidly periodic is simply a marketing ploy and an executive attention grabber. When managers and executives accustomed to many man-months between deliveries get a whiff of the “30 day” guarantee, they: make a beeline to the nearest agile cathedral; gleefully kneel at the altar; and line up their dixie cups for the next round of kool-aid.

Any Obstacles?

In Scrum, one of the three questions every team member is supposed to answer at the daily standup meeting is: “Are there any obstacles in your way?“. BD00 often wonders how many people actually answer it, let alone really answer it…

And no, BD00 doesn’t really answer it. Been there and done that. As you might surmise, because of his uncivilized nature and lack of political savvy, it didn’t work out so well – so he stopped using that industry-best practice. But for you and your team, really answering the question works wonders – right?

The day soldiers stop bringing you their problems is the day you have stopped leading them. They have either lost confidence that you can help or concluded that you don’t care. Either case is a failure of leadership.” – Karl Popper

Burn Baby Burn

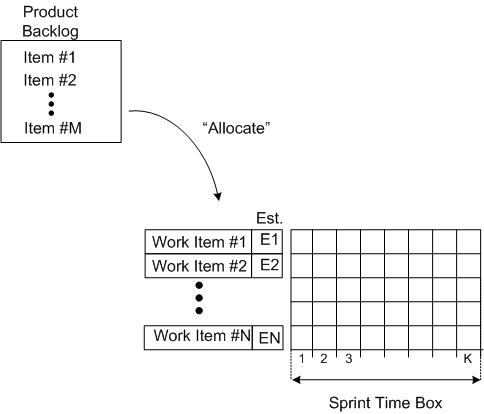

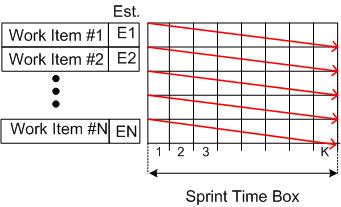

The “time-boxed sprint” is one of the star features of the Scrum product development process framework. During each sprint planning meeting, the team estimates how much work from the product backlog can be accomplished within a fixed amount of time, say, 2 or 4 weeks. The team then proceeds to do the work and subsequently demonstrate the results it has achieved at the end of the sprint.

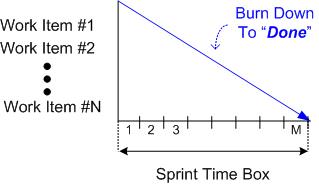

As a fine means of monitoring/controlling the work done while a sprint is in progress, some teams use an incarnation of a Burn Down Chart (BDC). The BDC records the backlog items on the ordinate axis, time on the abscissa axis, and progress within the chart area.

The figure below shows the state of a BDC just prior to commencing a sprint. A set of product backlog items have been somehow allocated to the sprint and the “time to complete” each work item has been estimated (Est. E1, E2….).

At the end of the sprint, all of the tasks should have magically burned down to zero and the BDC should look like this:

So, other than the shortened time frame, what’s the difference between an “agile” BDC and the hated, waterfall-esque, Gannt chart? Also, how is managing by burn down progress any different than the hated, traditional, Earned Value Management (EVM) system?

So, other than the shortened time frame, what’s the difference between an “agile” BDC and the hated, waterfall-esque, Gannt chart? Also, how is managing by burn down progress any different than the hated, traditional, Earned Value Management (EVM) system?

I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by – Douglas Adams

In practice, which of the outcomes below would you expect to see most, if not all, of the time? Why?

We need to estimate how many people we need, how much time, and how much money. Then we’ll know when we’re running late and we can, um, do something.

Shortcutting The Shortcut

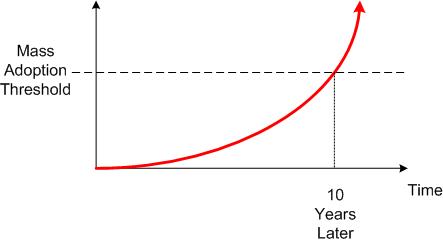

BD00 has heard from several sources that it takes about 10 years for a winning technology to make it into the mainstream. After starting off with a slow uptake due to fear and uncertainty, the floodgates open up and everybody starts leveraging the technology to make more money and greater products.

This 10 year rule of thumb surely applies to the “agile” movement, which recently celebrated its 10th anniversary. But as the new book below shows, the frenzy can get laughably outta control.

Not to rag too much on Mr. Goldstein, but sheesh. As if Scrum is not “fast” enough already? Now we’re patronizingly told that we need “intelligent” shortcuts to make it even faster. Plus, we idiots need to learn what these shortcuts are and how to apply them in a “step-by-step” fashion from a credentialed sage-on-a-stage. Hey, we must be idjets cuz, despite the beautiful simplicity of Scrum, Mr. Goldstein implies that we keep screwing up its execution.

As usual, BD00 hasn’t read the ground breaking new book. And he has no plan to read it. And he has no plan to stop writing about topics he hasn’t researched “deeply“. Thus, keep reminding yourself that:

King Of The Hill

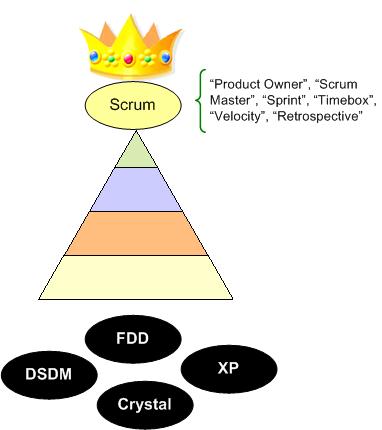

Scrum is an agile approach to software development, but it’s not the only agile approach. However, because of its runaway success of adoption compared to other agile approaches (e.g. XP, DSDM, Crystal, FDD), a lot of the pro and con material I read online seems to assume that Agile IS Scrum.

This nitpicking aside, until recently, I wondered why Scrum catapulted to the top of the agile heap over the other worthy agile candidates. Somewhere online, someone answered the question with something like:

“Scrum is king of the hill right now because it’s closer to being a management process than a geeky, code-centric set of practices. Thus, since enlightened executives can pseudo-understand it, they’re more likely to approve of its use over traditional prescriptive processes that only provide an illusion of control and a false sense of security.”

I think that whoever said that is correct. Why do you think Scrum is currently the king of the hill?

Related articles

- The Scrum Sprint Planning Meeting (bulldozer00.com)

- Scrum And Non-Scrum Interfaces (bulldozer00.com)

Scrum And Non-Scrum Interfaces

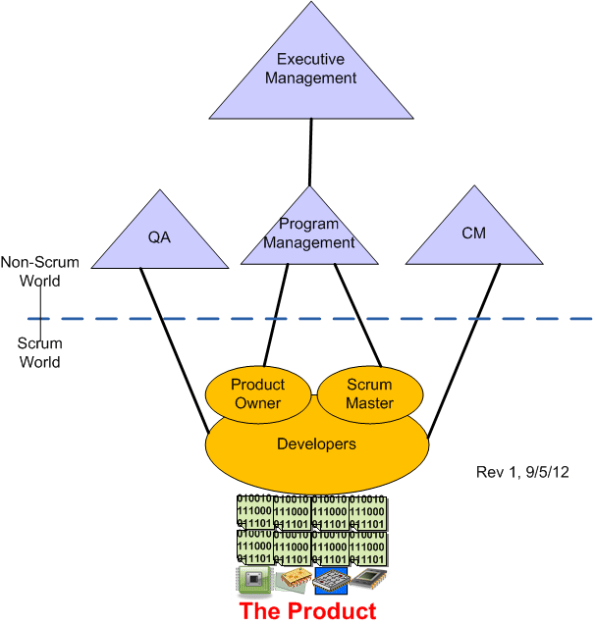

According to the short and sweet Schwaber/Sutherland Scrum Guide, a Scrum team is comprised of three, and only three, simple roles: the Product Owner, the Scrum Master, and the Developers. One way of “interfacing” a flat and collaborative Scrum team to the rest of a traditional hierarchical organization is shown below. The fewer and thinner the connections, the less impedance mismatch and the greater the chances of efficient success.

Regarding an ensemble of Scrum Developers, the guide states:

Scrum recognizes no titles for Development Team members other than Developer, regardless of the work being performed by the person; there are no exceptions to this rule.

I think (but am not sure) that the unambiguous “no exceptions” clause is intended to facilitate consensus-based decision-making and preclude traditional “titled” roles from making all of the important decisions.

So, what if your conservative org is willing to give Scrum an honest, spirited, try but it requires the traditional role of “lead(s)” on teams? If so, then from a pedantic point of view, the model below violates the “no exceptions” rule, no? But does it really matter? Should Scrum be rigidly followed to the letter of the law? If so, doesn”t that demand go against the grain of the agile philosophy? When does Scrum become “Scrum-but“, and who decides?

Related articles

- The Scrum Sprint Planning Meeting (bulldozer00.com)

- Bring Back The Old (bulldozer00.com)

- Ultimately And Unsurprisingly (bulldozer00.com)

- From Complexity To Simplicity (bulldozer00.com)

- Why I’m done with Scrum (lostechies.com)

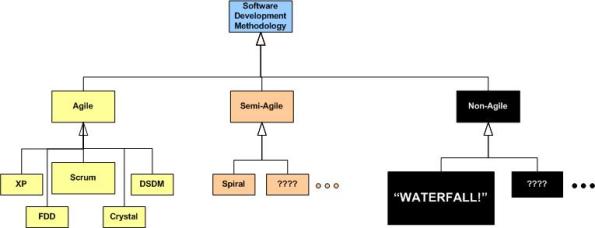

Methodology Taxonomy

Here’s a feeble attempt at sharing a taxonomy of well-known (to BD00) software development methodologies:

Got any others to add to revision 1? How about variations on the hated “WATERFALL!” class? Where should the sprawling RUP go? What about “Scrum-but“? Does “kanban” fit into this taxonomy, or is it simply a practice to be integrated within a methodology? What about “Lean“?

The Scrum Sprint Planning Meeting

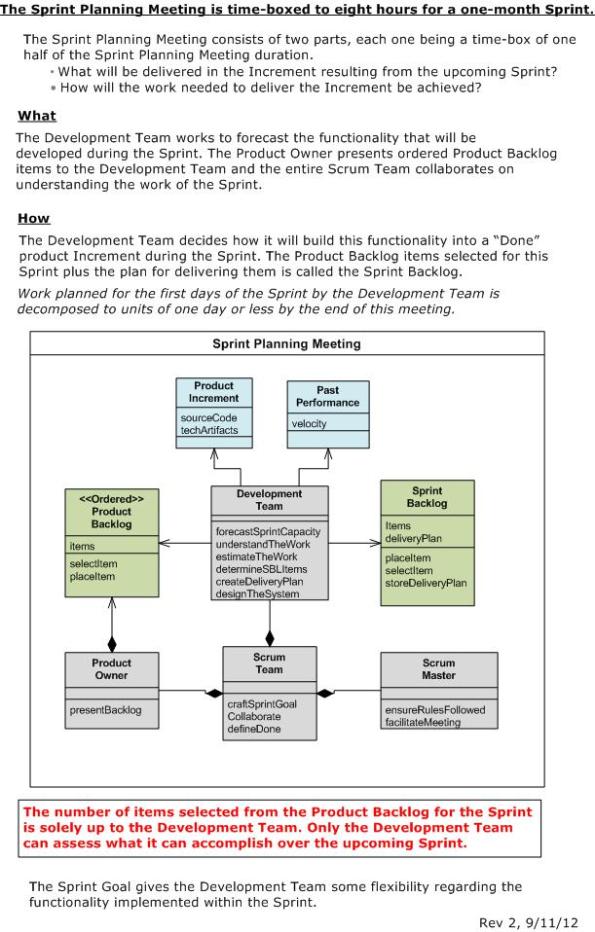

Since the UML Scrum Cheat Sheet post is getting quite a few page views, I decided to conjure up a class diagram that shows the static structure of the Scrum Sprint Planning Meeting (SPM).

The figure below shows some text from the official Scrum Guide. It’s followed by a “bent” UML class diagram that transforms the text into a glorious visual model of the SPM players and their responsibilities.

In unsuccessful Scrum adoptions where a hierarchical command & control mindset is firmly entrenched, I’ll bet that the meeting is a CF (Cluster-f*ck) where nobody fulfills their responsibilities and the alpha dudes dominate the “collaborative” decision making process. Maybe that’s why Ramblin’ Scott Ambler recently tweeted:

Everybody is doing agile these days. Even those that aren’t. – Scott Ambler

D’oh! and WTF! – BD00

Of course, BD00 has no clue what shenanigans take place during unsuccessful agile adoptions. In the interest of keeping those consulting and certification fees rolling in, nobody talks much about those. As Chris Argyris likes to say, they’re “undiscussable“. So, Shhhhhhh!

Bring Back The Old

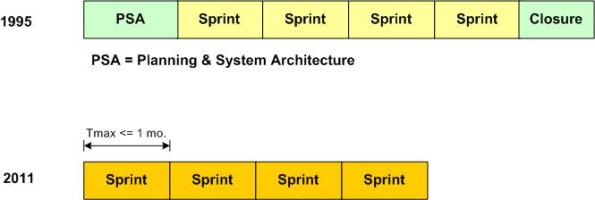

The figure below shows the phases of Scrum as defined in 1995 (“Scrum Development Process“) and 2011 (The 2011 Scrum Guide). By truncating the waterfall-like endpoints, especially the PSA segment, the development framework became less prescriptive with regard to the front and back ends of a new product development effort. Taken literally, there are no front or back ends in Scrum.

The well known Scrum Sprint-Sprint-Sprint-Sprint… work sequence is terrific for maintenance projects where the software architecture and development/build/test infrastructure is already established and “in-place“. However, for brand new developments where costly-to-change upfront architecture and infrastructure decisions must be made before starting to Sprint toward “done” product increments, Scrum no longer provides guidance. Scrum is mum!

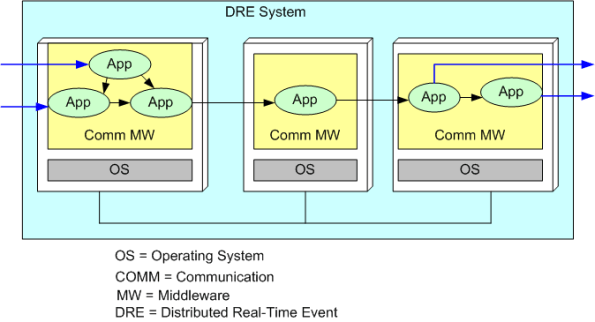

The figure below shows a generic DRE system where raw “samples” continuously stream in from the left and value-added info streams out from the right. In order to minimize the downstream disaster of “we built the system but we discovered that the freakin’ architecture fails the latency and/or thruput tests!“, a bunch of critical “non-functional” decisions and must be made and prototyped/tested before developing and integrating App tier components into a potentially releasable product increment.

I think that the PSA segment in the original definition of Scrum may have been intended to mitigate the downstream “we’re vucked” surprise. Maybe it’s just me, but I think it’s too bad that it was jettisoned from the framework.

The time’s gone, the money’s gone, and the damn thing don’t work!

From Complexity To Simplicity

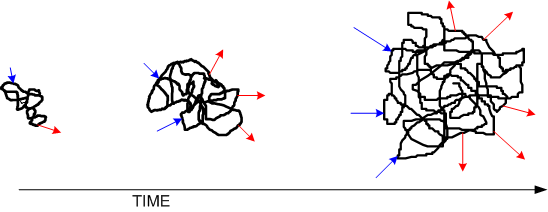

As the graphic below shows, when a system evolves, it tends to accrue more complexity – especially man-made systems. Thus, I was surprised to discover that the Scrum product development framework seems to have evolved in the opposite direction over time – from complexity toward simplicity.

The 1995 Ken Schwaber “Scrum Development Process“ paper describes Scrum as:

The 1995 Ken Schwaber “Scrum Development Process“ paper describes Scrum as:

Scrum is a management, enhancement, and maintenance methodology for an existing system or production prototype.

However, The 2011 Scrum Guide introduces Scrum as:

Scrum is a framework for developing and sustaining complex products.

Thus, according to its founding fathers, Scrum has transformed from a “methodology” into a “framework“.

Even though most people would probably agree that the term “framework” connotes more generality than the term “methodology“, it’s arguable whether a framework is simpler than a methodology. Nevertheless, as the figure below shows, I think that this is indeed the case for Scrum.

In 1995, Scrum was defined as having two bookend, waterfall-like, events: PSA and Closure. As you can see, the 2011 definition does not include these bookends. For good or bad, Scrum has become simpler by shedding its junk in the trunk, no?

The most reliable part in a system is the one that is not there; because it isn’t needed. (Middle management?)

I think, but am not sure, that the PSA event was truncated from the Scrum definition in order to discourage inefficient BDUF (Big Design Up Front) from dominating a project. I also think, but am not sure, that the Closure event was jettisoned from Scrum to dispel the myth that there is a “100% done” time-point for the class of product developments Scrum targets. What do you think?

Related articles

- Scrum Cheat Sheet (bulldozer00.com)

- Ultimately And Unsurprisingly (bulldozer00.com)

- Introduction to scrum (slideshare.net)

- Scrum Master, a management position? (scrumguru.wordpress.com)

- Developing, and succeeding, with Scrum (techworld.com.au)