Archive

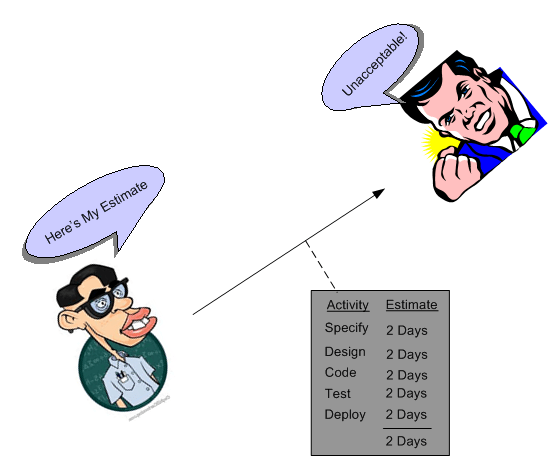

OMITTED ACTIVITIES!

The best book I’ve read (so far) on software estimation is Steve McConnell’s “Software Estimation: Demystifying the Black Art“. Steve is one of the most pragmatic technical authors I know. His whole portfolio of books is worth delving into.

Prior to describing many practical and “doable” estimation practices, Steve presents a dauntingly depressive list of estimation error sources:

- Unstable requirements

- Unfounded optimism

- Subjectivity and bias

- Unfamiliar application domain area

- Unfamiliar technology area

- Incorrect conversion from estimated time to project time (for example, assuming the project team will focus on the project eight hours per day, five days per week)

- Misunderstanding of statistical concepts (especially adding together a set of “best case” estimates or a set of “worst case” estimates)

- Budgeting processes that undermine effective estimation (especially those that require final budget approval in the wide part of the Cone of Uncertainty)

- Having an accurate size estimate, but introducing errors when converting the size estimate to an effort estimate

- Having accurate size and effort estimates, but introducing errors when converting those to a schedule estimate

- Overstated savings from new development tools or methods

- Simplification of the estimate as it’s reported up layers of management, fed into the budgeting process, and so on

- OMITTED ACTIVITIES!

But wait! We’re not done. That last screaming bullet, OMITTED ACTIVITIES!, needs some elaboration:

- Glue code needed to use third-party or open-source software

- Ramp-up time for new team members

- Mentoring of new team members

- Management coordination/manager meetings

- Requirements clarifications

- Maintaining the scripts required to run the daily build

- Participation in technical reviews

- Integration work

- Processing change requests

- Attendance at change-control/triage meetings

- Maintenance work on previous systems during the project

- Performance tuning

- Administrative work related to defect tracking

- Learning new development tools

- Answering questions from testers

- Input to user documentation and review of user documentation

- Review of technical documentation

- Reviewing plans, estimates, architecture, detailed designs, stage plans, code, test cases

- Vacations

- Company meetings

- Holidays

- Sick days

- Weekends

- Troubleshooting hardware and software problems

It’s no freakin’ wonder that the vast majority of software-intensive projects are underestimated, no? To add insult to injury, the unspoken pressure from the “upper layers” to underestimate the activities that ARE actually included in a project plan seals the deal for “perceived” future failure, no? It’s also no wonder that after a few years, good technical people who feel that hands-on creative work is their true calling start agonizing over whether to get the hell out of such a failure-inducing system and make the move on up into the world of politics, one-upsmanship, feigned collaboration, dubious accomplishment, and strategic self-censorship. Bummer for those people and the orgs they dwell in. Bummer for “the whole“.

Not Applicable?

No Lessons Learned II

Since my post on the JTRS fiasco generated more blog traffic than usual, this post is based on the same theme – the failure of a big, multi-techonology, socio-technical project. Today’s topic is the termination of the Army’s massive Future Combat Systems (FCS) program in 2009 after 6 years of development and gobs of spent taxpayer money. Actually, some face-saving was achieved on this boondoggle since the monolithic FCS program was replaced by several smaller, fragmented programs.

From a slew of pages I bookmarked on Delicious.com over the years, I pieced together the following timeline of events for the FCS program.

1) The FCS program is formally kicked off in 2003, with much fanfare, of course.

2) In August 2005, the program met 100% of the criteria in its most important milestone to date, Systems of Systems Functional Review. (Whoo Hoo, the “paper” docs were perfect!)

3) January 24, 2008. Congressional investigators express “concern” that the lines of code have nearly doubled since development began in 2003. And they question the Army’s oversight of a far-flung project involving more than 2,000 developers and dozens of contractors working across the nation. The Government Accountability Office, Congress’s watchdog, says the Army underestimated the undertaking. When the software project began, investigators say the Army estimated it needed 33.7 million lines of code; it’s now 63.8 million — about three times the number for the Joint Strike Fighter aircraft program. The software program “started prematurely. They didn’t have a solid knowledge base,” said Bill Graveline, a GAO official involved in the government’s ongoing review. “They didn’t really understand the requirements.”

4) Mar 18, 2008. Setbacks in the Army’s development of its software requirements for FCS due to the immaturity of the program and the aggressive pace of the Army’s development schedule, however, have led to delays, errors and omissions in the development of essential software packages for the program, while flaws in those packages have in turn delayed or threatened other development efforts, GAO said. Developers for five major software packages, for example, said that the high-level requirements they received from the Army were poorly defined, late or missing during the development process, GAO said.

5) June 13, 2008. Possible budget cuts, a change of administration and the Pentagon’s focus on supporting operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have ratcheted up pressure on the program just when it is showing tangible signs of progress after five years of work and almost $15 billion in taxpayer money invested.

6) Mar 02, 2009 The systems integrators heading the Army’s Future Combat Systems program have confirmed that development of the hardware and software required for the program’s vehicles and weapons systems is proceeding as planned. (Boeing Co. and Science Applications International Corp. are the lead systems integrators for the $87 billion FCS program.)

7) June 23, 2009. The memorandum issued confirms the recommendations made earlier this year by Defense Secretary Robert Gates to replace the single, giant program with a number of smaller modernization efforts.

FCS, particularly the manned combat vehicle portion, did not reflect the anti-insurgency lessons learned in Iraq and Afghanistan. – Robert Gates

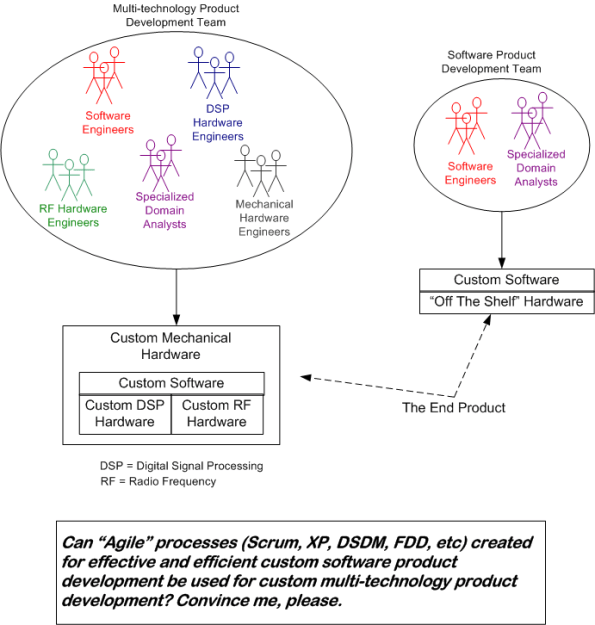

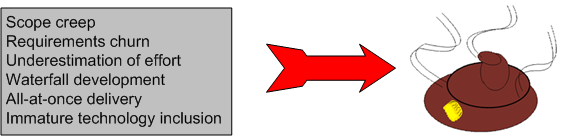

So, let’s see what went wrong: ambiguous and inconsistent and misunderstood requirements, gross underestimation of effort, immature technologies, “aggressive” schedules. Sound familiar? Yawn. Same old, same old.

No Lessons Learned

Because I’m fascinated by the causes and ubiquity of socio-technical project explosions, I try to follow technical press reports on the status of big government contracts. Here’s a recent article detailing the demise of the DoD’s Joint Tactical Radio System (JTRS): “How to blow $6 billion on a tech project“.

Even though the reasons for big, software-intensive, multi-technology project failures have been well known for decades, disasters continue to be hatched and cancelled daily around the world by both public and private institutions everywhere – except yours, of course.

What follows are some snippets from the Ars Technica article and the JTRS wikipedia entry. The well-known, well-documented, contributory causes to the JTRS project’s demise are highlighted in bold type.

When JTRS and GMR launched, the services broke out huge wish lists when they drafted their initial requests for proposals on individual JTRS programs. While they narrowed some of these requirements as the programs were consolidated, requirements were constantly revised before, during, and after the design process.

In hindsight, the military badly underestimated the challenges before it.

First and foremost was the software development problem. When JTRS started, software-defined radio (SDR) was still in its infancy. The project’s SCA architecture allowed software to manipulate field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) in the radio hardware to reconfigure how its electronics functioned, exposing those FPGAs as CORBA objects. But when development began, hardware implementations of CORBA for FPGAs didn’t really exist in any standard form.

Moving code for a waveform from one set of radio hardware to another didn’t just mean a recompile—it often meant significant rewrites to make it compatible with whatever FGPAs were used in the target radio, then further tweaking to produce an acceptable level of performance. The result: the challenge of core development tasks for each of the initial designs was often grossly underestimated. Some of those issues have been addressed by specialized CORBA middleware, such as PrismTech’s OpenFusion, but the software tools have been long in coming.

When JTRS began, there was no WiFi, no 3G or no 4G wireless, and commercial radio communications was relatively expensive. But the consumer industry didn’t even look at SDR as a way to keep its products relevant in the future. Now, ASIC-based digital signal processors are cheap, and new products also tend to include faster chips and new hardware features; people prefer buying a new $100 WiFi router when some future 802.11z protocol appears instead of buying a $3,000 wireless router today that is “future proofed” (and you can’t really call anything based on CORBA “future proofed”).

“If JTRS had focused on rapid releases and taken a more modular approach, and tested and deployed early, the Army could have had at least 80 percent of what it wanted out of GMR today, instead of what it has now—a certified radio that it will never deploy.”

Having an undefined technical problem is bad enough, but it gets even worse when serious “scope creep” sets in during a 15-year project.

Each of the five sub-programs within JTRS aimed not at an incremental goal, but at delivering everything at once. That was a recipe for disaster.

By 2007 (10 years after start) the JTRS program as a whole had spent billions and billions—without any radios fielded.

In the fall of 2011, after 13 years of toil and $6B of our money wasted, the monster was put out of its misery. It was cancelled on October 2011 by the United States Undersecretary of Defense:

Our assessment is that it is unlikely that products resulting from the JTRS GMR development program will affordably meet Service requirements, and may not meet some requirements at all. Therefore termination is necessary.

And here’s what we, the taxpayers, have to show for the massive investment:

After 13 years in the pipeline, what those users saw was a radio that weighed as much as a drill sergeant, took too long to set up, failed frequently, and didn’t have enough range. (D’oh! and WTF!)

Respect From The Top, Disdain From The Bottom

In Scott Berkun‘s blog post, “Why Project Managers (PM) get no respect“, he gets to the heart of his assertion of why “output producers” don’t harbor much professional respect for “output managers“:

The core problem is perspective. Our culture does not think of movie directors, executive chefs, astronauts, brain surgeons, or rock stars as project managers, despite the fact that much of what these cool, high profile occupations do is manage projects. Everything is a project. The difference is these individuals would never describe themselves primarily as project managers. They’d describe themselves as directors, architects or rock stars first, and as a projects manager or team leaders second. They are committed first to the output, not the process. And the perspective many PMs have is the opposite: they are committed first to the process, and their status in the process, not the output.

If one doesn’t understand the “project output” to some degree, especially what makes for a high quality output, there is no choice but to focus on process over output. And as one goes higher up in the corpo status chain, the preference for concentrating on process and its artifacts (spreadsheets, specifications, presentations, status reports) over output tends to increase because meta-managers have much in common with lesser “output managers” and not much in common with “output producers“. It is what it is, and unless so-called process champions are continuously educated on the specific types of “outputs” their institutions produce, it will remain what it is.

Mistake Recognition

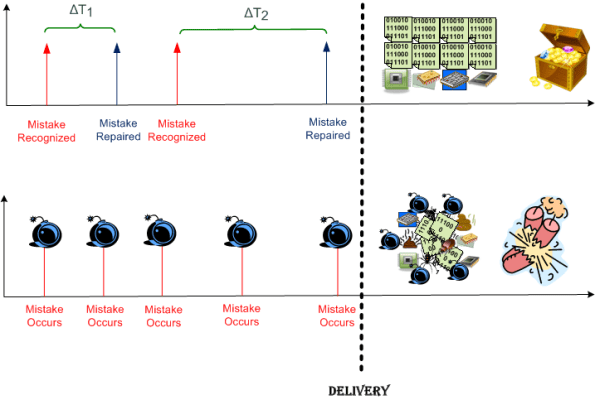

First question: Is “mistake recognition” allowed in your organization? Second question, if, and only if, the answer to the first question is “yes“: How many different “enabler” groups are required by your process to “have a say” in the path from “recognized” to “repaired”

If the answer to the first question is a cultural “no“, then as the lower trace in the dorky diagram shows, out the door your cannonballs go!

All Forked Up!

BD00 posits that many software development orgs start out with good business intentions to build and share a domain-specific “platform” (a.k.a. infrastructure) layer of software amongst a portfolio of closely related, but slightly different instantiations of revenue generating applications. However, as your intuition may be hinting at, the vast majority of these poor souls unintentionally, but surely, fork it all up. D’oh!

The example timeline below exposes just one way in which these colossal “fork ups” manifest. At T0, the platform team starts building the infrastructure code (common functionality such as inter-component communication protocols, event logging, data recording, system fault detection/handling, etc) in cohabitation with the team of the first revenue generating app. It’s important to have two loosely-coupled teams in action so that the platform stays generic and doesn’t get fused/baked together with the initial app product.

At T1, a new development effort starts on App2. The freshly formed App2 team saves a bunch of development cost and time upfront by reusing, as-is, the “general” platform code that’s being co-evolved with App1.

Everything moves along in parallel, hunky dory fashion until something strange happens. At T2, the App2 product team notices that each successive platform update breaks their code. They also notice that their feature requests and bug reports are taking a back seat to the App1 team’s needs. Because of this lack of “service“, at T3 the frustrated App2 team says “FORK IT!” – and they literally do it. They “clone and own” the so-called common platform code base and start evolving their “forked up” version themselves. Since the App2 team now has to evolve both their App and their newly born platform layer, their schedule starts slipping more than usual and their prescriptive “plan” gets more disconnected from reality than it normally does. To add insult to injury, the App2 team finds that there is no usable platform API documentation, no tutorial/example code, and they must pour through 1000s of lines of code to figure out how to use, debug, and add features to the dang thing. Development of the platform starts taking more time than the development of their App and… yada, yada, yada. You can write the rest of the story, no?

So, assume that you’ve been burned once (and hopefully only once) by the ubiquitous and pervasive “forked up” pattern of reuse. How do you prevent history from repeating itself (yet again)? Do you issue coercive threats to conform to the mission? Do you swap out individuals or whole teams? Do you send your whole org to a 3 day Scrum certification class? Will continuous exhortations from the heavens work to change “mindsets“? Do you start measuring/collecting/evaluating some new metrics? Do you change the structure and behaviors of the enclosing social system? Is this solely a social problem; solely a technical problem? Do you not think about it and hope for the best – the next time around?

Fellow Tribe Members

Being a somewhat skeptical evaluator of conventional wisdom myself, I always enjoy promoting heretical ideas shared by unknown members of my “tribe“. Doug Rosenberg and Matt Stephens are two such tribe members.

Waaaay back, when the agile process revolution against linear, waterfall process thinking was ignited via the signing of the agile manifesto, the eXtreme Programming (XP) agile process burst onto the scene as the latest overhyped silver bullet in the software “engineering” community. While a religious cult that idolized the infallible XP process was growing exponentially in the wake of its introduction, Doug and Matt hatched “Extreme Programming Refactored: The Case Against XP“. The book was a deliciously caustic critique of the beloved process. Of course, Matt and Doug were showered with scorn and hate by the XP priesthood as soon as the book rolled off the presses.

Well, Doug and Matt are back for their second act with the delightful “Design Driven Testing: Test Smarter, Not Harder“. This time, the duo from hell pokes holes in the revered TDD (Test Driven Design) approach to software design – which yet again triggered the rise of another new religion in the software community; or should I say “commune“.

BD00’s hat goes off to you guys. Keep up the good work! Maybe your next work should be titled “Lowerarchy Design: The Case Against Hierarchy“.

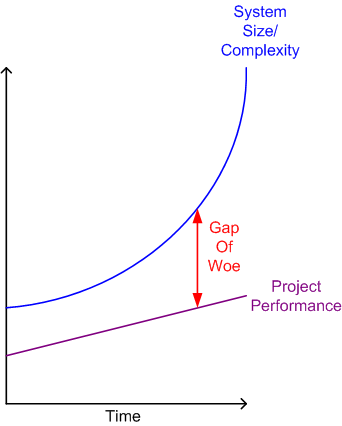

The Gap Of Woe

In “Why Software Fails”, the most common factors that contribute to software project failure are enumerated as:

- Unrealistic or unarticulated project goals

- Inaccurate estimates of needed resources

- Badly defined system requirements

- Poor reporting of the project’s status

- Unmanaged risks

- Poor communication among customers, developers, and users

- Use of immature technology

- Inability to handle the project’s complexity

- Sloppy development practices

- Poor project management

- Stakeholder politics

- Commercial pressures

Yawn. These failure factors have remained the same for forty years and there are no silver bullet(s) in sight. Oh sure, tools and practices and methodologies have “slightly” improved project performance over the decades, but the increase in size/complexity of the software systems we develop is outpacing performance improvement efforts by a large margin.

From Within, From Without

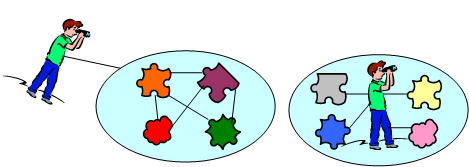

With exceptions (and there are always exceptions) everyone knows that the view “from within” is different than the view “from without“.

While viewing “from without“, there is typically less emotional attachment of the viewer to the viewed. The more one is attached to the view “from within“, the more difficult it is to extricate oneself from that view and form a secondary view “from without“.

On product development projects, it’s much easier for a project team member to step outside of the intricate details “from within” to form a view “from without” than it is for an “outsider” to form a view “from within“. But just because it’s easier, it doesn’t mean that it’s done often.

This “from within” and “from without” crap is simply a twist on the old “put yourself in someone else’s shoes” advice…..