Archive

Formal Review Chain

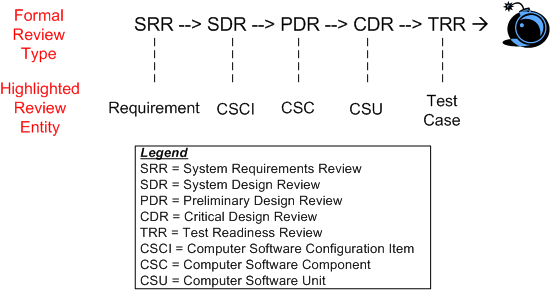

On big, multi-year, multi-million dollar software development projects, a series of “high-ceremony” formal reviews are almost always required to be held by contract. The figure below shows the typical, sequential, waterfall review lineup for a behemoth project.

The entity below each high ceremony review milestone is “supposedly” the big star of the review. For example, at SDR, the structure and behavior of the system in terms of the set of CSCIs that comprise the “whole” are “supposedly” reviewed and approved by the attendees (most of whom are there for R&R and social schmoozing). It’s been empirically proven that the ratio of those “involved” to those “responsible” at reviews in big projects is typically 5 to 1 and the ratio of those who understand the technical content to those who don’t is 1 to 10. Hasn’t that been the case in your experience?

The figure below shows a more focused view of the growth in system artifacts as the project supposedly progresses forward in the fantasy world of behemoth waterfall disasters, uh, I mean projects. Of course, in psychedelic waterfall-land, the artifacts of any given stage are rigorously traceable back to those that were “designed” in the previous stage. Hasn’t that been the case in your experience?

In big waterfall projects that are planned and executed according to the standard waterfall framework outlined in this post, the outcome of each dog-and-pony review is always deemed a great success by both the contractee and contractor. Backs are patted, high fives are exchanged, and congratulatory e-mails are broadcast across the land. Hasn’t that been the case in your experience?

No Man’s Land

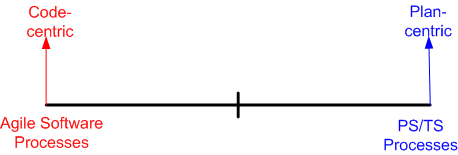

Having recently just read my umpteenth Watts Humphrey book on his PSP/TSP (Personal Software Process/Team Software Process) methodology, I find myself struggling, yet again, to reconcile his right wing thinking with the left wing “Agile” software methodologies that have sprouted up over the last 10 years as a backlash against waterfall-like methodologies. This diagram models the situational tension in my hollow head:

It’s not hard to deduce that prescriptive, plan-centric processes are favored by managers (at least those who understand the business of software) and demonstrative, code-centric processes are favored by developers. Duh!

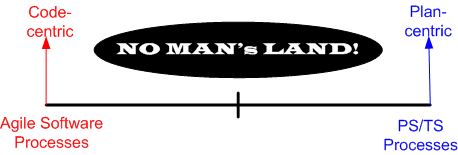

Advocates of both the right and the left have documented ample evidence that their approach is successful, but neither side (unsurprisingly) willingly publicizes their failures much. When the subject of failure is surfaced, both sides always attribute messes to bad “implementations” – which of course is true. IMHO, given a crack team of developers, project managers, testers, and financial sponsors, ANY disciplined methodology can be successful – those on the left, those on the right, or those toiling in NO MAN’s LAND.

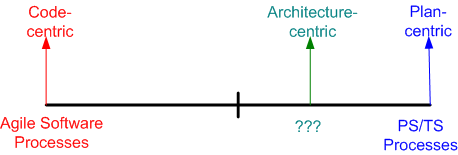

l’ve been the anointed software “lead” on two, < 10 person, software teams in the past. Both as a lead and an induhvidual contributor, the approach I’ve always intuitively taken toward software development can be classified as falling into “no man’s land“. It’s basically an informal, but well-known, Brooksian, architecture-centric, strategy that I’d characterize as slightly right-leaning:

As far as I know, there’s no funky, consensus-backed, label like “semi-agile” or “lean planning” to capture the essence of architecture-centric development. There certainly aren’t any “certification” training courses or famous promoters of the approach. This book, which I discovered and read after I’d been designing/developing in this mundane way for years, sort of covers the process that I repeatedly use.

In my tortured mind (and you definitely don’t want to go there!), architecture-centricity simply means “centered on high level blueprints“. Early on, before the horses are let out of the barn and massive, fragmented, project effort starts churning under continuous pressure from management for “status“, a frantic iterative/sketching/bounding/synthesis activity takes place. With a visible “rev X” architecture in hand (one that enumerates the structural elements, their connectivity, and the macro behavior that the system must manifest) for guidance, people can then be assigned to the sparsely defined, but bounded, system elements so that they can create reasonable “Rev 0” estimates and plans. The keys are that only one or two or three people record the lay of the land. Subsequently, the element assignees produce their own “Rev 0” estimates – prior to igniting the frenetic project activity that is sure to follow.

In a nutshell, what I just described is the front-end of the architecture-centric approach as I practice it; either overtly or covertly. The subsequent construction activities that take place after a reasonably solid, lightweight, “rev X”, architecture (or equivalent design artifact for smaller scale projects) has been recorded and disseminated are just details. Of course, I’m just joking in that last sentence, but unless the macro front end is secured and repeatedly used as the “go to bible” shortly after T==start, all is lost – regardless of the micro-detailed practices (TDD, automated unit tests, continuous integration, continuous delivery, yada yada yada) that will follow. But hey, the content of this post is just Bulldozer00’s uncredentialed and non-expert opinion, so don’t believe a word of it.

Mangled Mess

“Too much documentation can be just as bad as no documentation” – Unknown

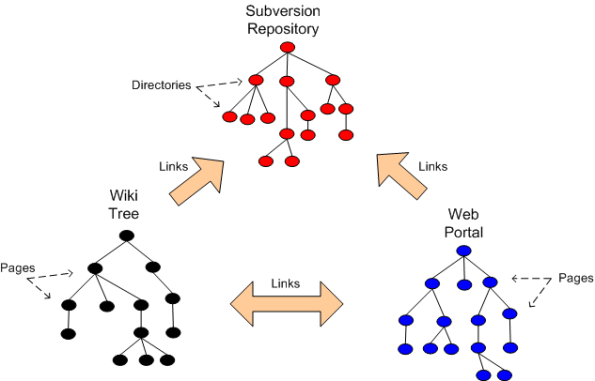

Assume that a big software project has chosen to use the three types of databases below to store and maintain technical information about a product under development: planning artifacts, trade studies, requirements artifacts, design artifacts, test cases & results, source code, installation instructions, developer guidance, user guidance.

Unless one is careful in defining and disseminating to the team the “what goes where” criteria, a fragmented and ambiguously duplicitous mass of confusion can emerge quicker than you can say “WTF?“.

Ambivalence

Prominent and presidentially decorated software process guru Watts Humphrey passed away last year. Over the years, I’ve read a lot of his work and I’ve always been ambivalent towards his ideas and methods. On the one hand, I think he’s got it right when he says Peter-Drucker-derived things like:

Since managers don’t and can’t know what knowledge workers do, they can’t manage knowledge workers. Thus, knowledge workers must manage themselves.

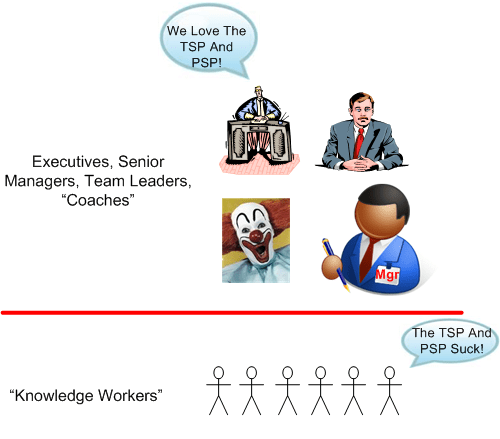

On the other hand, I’m turned off when he starts promoting his arcane and overly-pedantic TSP–PSP methodology. To me, his heavy, right wing measurement and prescriptive planning methods are an accountant’s dream and an undue burden on left leaning software development teams. Also, in at least his final two books, he targets his expert TSP-PSP way at “executives, senior managers, coaches and team leaders” while implying that knowledge workers are “them” in the familiar, dysfunctional “us vs. them” binary mindset (that I suffer from too).

I really want to like Watts and his CMMI, TSP-PSP babies, but I just can’t – at least at the moment. How about you? It would be kool if I received a bunch of answers from a mixture of managers and “knowledge workers“. However, since this blog is read by about 10 people and I have no idea whether they’re knowledge workers or managers or if they even heard of TSP-PSP or Watts Humphrey, I most likely won’t get any. 🙂

I really want to like Watts and his CMMI, TSP-PSP babies, but I just can’t – at least at the moment. How about you? It would be kool if I received a bunch of answers from a mixture of managers and “knowledge workers“. However, since this blog is read by about 10 people and I have no idea whether they’re knowledge workers or managers or if they even heard of TSP-PSP or Watts Humphrey, I most likely won’t get any. 🙂

The Boundary

Mr. Watts Humphrey‘s final book, titled “Leadership, Teamwork, and Trust: Building a Competitive Software Capability” was recently released and I’ve been reading it online. Since I’m in the front end of the book, before the TSP–PSP crap, I mean “stuff“, is placed into the limelight for sale, I’m enjoying what Watts and co-author James W. Over have written about the 21st century “management of knowledge workers problem“. Knowledge workers manipulate knowledge in the confines of their heads to create new knowledge. Physical laborers manipulate material objects to create new objects. Since, unlike physical work, knowledge work is invisible, Humphrey and Over (rightly) assert that knowledge work can’t be managed by traditional, early 20th century, management methods. In their own words:

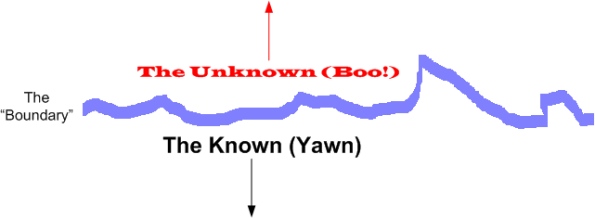

Knowledge workers take what is known, and after modifying and extending it, they combine it with other related knowledge to actually create new knowledge. This means they are working at the boundary between what is known and what is unknown. They are extending our total storehouse of knowledge, and in doing so, they are creating economic value. – Watts Humphrey & James W. Over

But Watts and Over seem inconsistent to me (and it’s probably just me). They talk about the boundary ‘tween the known and the unknown, yet they advocate the heavyweight pre-planning of tasks down to the 10 hour level of granularity. When you know in advance that you’ll be spending a large portion of your time exploring and fumbling around in unknown territory, it’s delusional for others who don’t have to do the work themselves to expect you to chunk and pre-plan your tasks in 10 hour increments, no?

Nothing is impossible for the man who doesn’t have to do it himself. – A. H. Weiler

Mangled Model

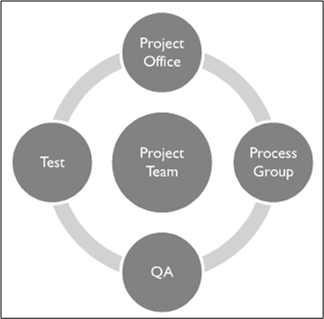

In their book, “Leadership, Teamwork, and Trust: Building a Competitive Software Capability“, Watts Humphrey and James Over model a typical software project system via the diagram below (note that they have separate Quality Assurance and Test groups and they put the “project office” on top).

Bulldozer00 would have modeled the typical project system like this:

Of course, the immature and childish BD00 model would be “inappropriate” for inclusion into a serious book that assumes impeccable, business-like behavior and maturity emanating from each sub-group. Oh, and the book wouldn’t sell many copies to the deep pocketed audience that it targets. D’oh!

When The Spigot Runs Dry

It was recently hinted to me that, for a legitimate business reason, the fun and exciting distributed systems IR&D (Internal Research and Development) software project that I’m working on might get canned. I sadly agree that if there are no customers for a product, and day-to-day fires are burning all over the place, it’s most definitely a legitimate business reason to turn off the financial spigot.

In addition to the “hint“, several important technical people have been reassigned to other maintenance projects. Bummer, but shite happens.

Marshal Law

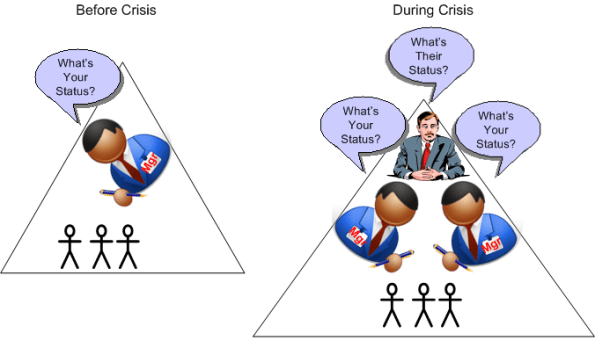

In a time of crisis, some “leadership” experts promote imposing the corpo equivalent of marshal law via the execution of more top-down control and discipline in the form of more frequent, multi-layered, financial reviews and detailed status reporting.

The thinking behind the “more control” approach is that by shining the light more often, and at a higher intensity, on those directly-in-the-soup will cause the crisis to dissolve. Another unquestioned assumption behind the “more control” approach is that the light-shiners will be able to better understand the real problems behind the crisis and offer “helpful” solution idea candidates – inspiring the troops to success.

Sounds great, right? Let’s switch gears, step into the deliciously diabolic role of devil’s advocate, and ask “what’s wrong with this picture?“. Are these thoughts missing:

- those doing the shining may be responsible for the mess in the first place but don’t realize it.

- those doing the shining have been so disconnected from the real world for so long that they are incapable of understanding the problem details well enough to help?

- those being illuminated will batten down the hatches, narrow their thinking, and withhold important information if they think it can be used against them.

Nah, probably not. After all, it’s a no brainer that the best and brightest problem solvers and decision makers sit at the top of the pyramid. If you don’t believe me, simply ask them.

On the other hand, a different pool of leadership experts promotes the unintuitive loosening of controls and less formality in a time of crisis – to allow more ideas from more people to surface and have a chance of resolving the crisis. Which approach do you think has a better chance of success?

On the other hand, a different pool of leadership experts promotes the unintuitive loosening of controls and less formality in a time of crisis – to allow more ideas from more people to surface and have a chance of resolving the crisis. Which approach do you think has a better chance of success?

Don’t try to address difficulties by adding more meetings and management. More meetings plus more documentation plus more management does not equal more success. – NASA SW Dev Approach

Product Team

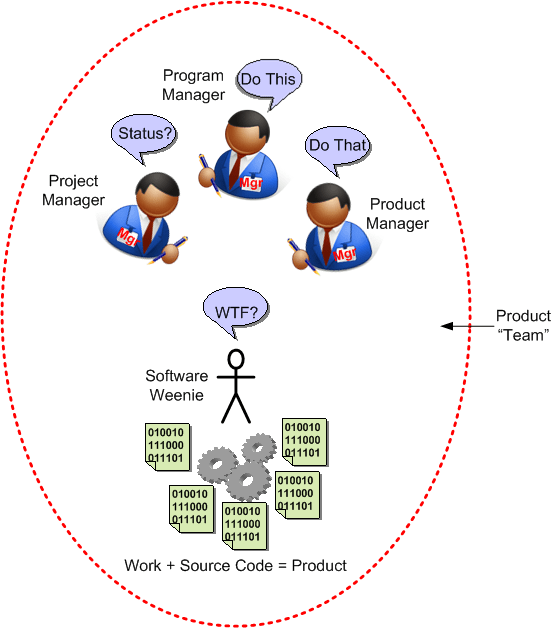

How can a software project have more managers and pseudo-managers “working” on it than developers – you know, those fungible people who write, debug, and test the product code that is the source of the borg’s income. You would think that this comically dysfunctional practice would stick out like a sore thumb and somebody upstairs would put the kabosh on it, no?

The Wevo Approach

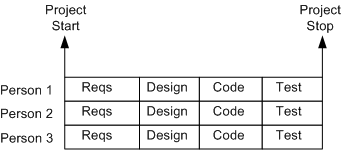

The figure below shows an example of a one-size-fits-all, waterfall schedule template that’s prevalent at many old school software companies. It sure looks nice, squeaky clean, and controllable, but as everyone knows, it’s always wrong. Out of fear or apathy, almost no one speaks out against this “best practice“, but those who do are quickly slapped down by the anointed controllers and meta-controllers of the project.

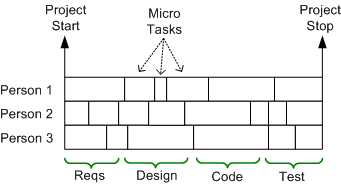

A more insidious, micro-grained, version of this waterboarding fiasco is shown below. It’s a self-medicating attempt to amplify the illusion of control that’s envisioned to take place throughout the execution of the project. Since schedules are concocted before an architecture or design has been reasonably sketched out and no one can possibly know up front what all the micro tasks are, let alone how long they’ll take (unless the project is to dig ditches), it’s monstrously wrong too. But shush, don’t say a word.

Once a monstrosity like this is baked into a huge Microsoft Project file or company proprietary scheduling document, those who conjured up the camouflage auto-become loathe to modify it, even as the situation dynamically changes during the death march. Once the project starts churning, new unforeseen “popup” tasks emerge and some pre-planned micro-tasks become obsolete. These events disconnect the schedule from reality quicker than you can say “WTF?“.

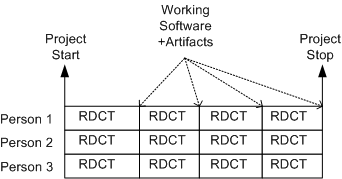

Moving on to a sunnier disposition, the template below shows a more “sane“, but not infallible, method of scheduling. It’s a model of the incremental “evo” strategy that I first stumbled upon from Tom Gilb – a bazillion years before the agile movement rose to prominence. In the evo(lutionary) approach, stable working software becomes visible early with each RDCT cycle and it grows and matures as the messy (it’s always messy) project lurches forward.

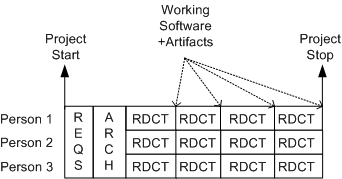

The figure below shows a tweaked version of the evo model. It’s a hybrid concoction of the waterboard and evolutionary development approaches – the “wevo“. Some upfront requirements and architecture exploration/definition/specification is performed by the elected team technical leaders before staffing up for the battle against the possibility of building a BBoM. The purpose of the upfront requirements and architecture efforts are to address major cross-cutting concerns and establish contextual boundaries – before letting the dogs loose.

Of course, the wevo approach is not enough. Another necessary but insufficient requirement is that the team leaders dive into the muck with the “coders” after the cross-cutting requirements and architecture definition activities have produced a stable, understandable blueprint. No jargon spewing software “rocketects” or “pure” software project leads allowed – everyone gets dirty – and for the duration.