Archive

Seven Unsurprising Findings

In the National Acadamies Press’s “Summary of a Workshop for Software-Intensive Systems and Uncertainty at Scale“, the Committee on Advancing Software-Intensive Systems Producibility lists 7 findings from a review of 40 DoD programs.

- Software requirements are not well defined, traceable, and testable.

- Immature architectures; integration of commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) products; interoperability; and obsolescence (the need to refresh electronics and hardware).

- Software development processes that are not institutionalized, have missing or incomplete planning documents, and inconsistent reuse strategies.

- Software testing and evaluation that lacks rigor and breadth.

- Lack of realism in compressed or overlapping schedules.

- Lessons learned are not incorporated into successive builds—they are not cumulative.

- Software risks and metrics are not well defined or well managed.

Well gee, do ya think they missed anything? What I’d like to know is what, if anything, they found right with those 40 programs. Anything? Maybe that would help more than ragging on the same issues that have been ragged on for 40 years.

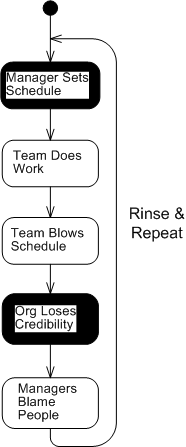

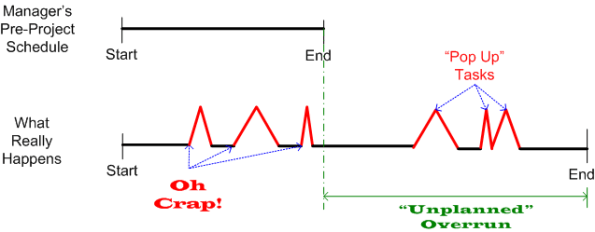

My fave is number five (with number 1 a close second). When schedules concocted by non-technical managers without any historical backing or input from the people who will be doing the work are publicly promised to customers, how can anyone in their right mind assert that they’re “realistic“? The funny thing is, it happens all the time with nary a blink – until the fit hits the shan, of course. D’oh!

Meeting schedules based on historically tracked data and input from team members is challenging enough, but casting an unsubstantiated schedule in stone without an explicit policy of periodically reassessing it on the basis of newly acquired knowledge and learning as a project progresses is pure insanity. Same old, same old.

I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by. – Douglas Adams

Truckin’

Truckin’ got my chips cashed in. Keep truckin’, like the do-dah man. – Grateful Dead

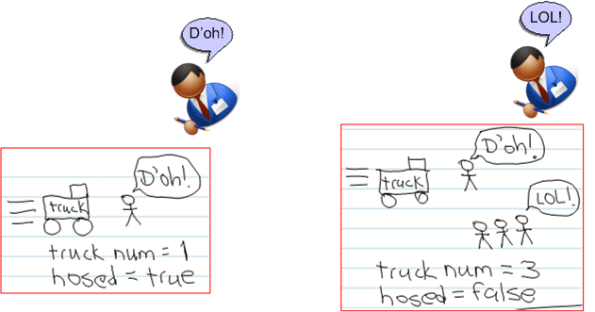

One of the funny concepts that someone concocted a while back is called the “truck number“. The truck number is the number of critical people on a project that would need to get hit by a truck (and die) before the project is guaranteed to get completely hosed.

A couple of ways to increase your truck number is to minimize specialization of roles and to effect job rotations in areas of expertise that aren’t orthogonal from each other. However, if you think of, and treat all of, the people on your project as quickly replaceable cogs, then you erroneously and naively assume that the truck number is equal to the number of people on your project. Thus, the bigger the project, the better. Whoo Hoo!

kkk

Traceability Woes

For safety-critical systems deployed in aerospace and defense applications where people’s lives may at be at stake, traceability is often talked about but seldom done in a non-superficial manner. Usually, after talking up a storm about how diligent the team will be in tracing concrete components like source code classes/functions/lines and hardware circuits/boards/assemblies up the spec tree to the highest level of abstract system requirements, the trace structure that ends up being put in place is often “whatever we think we can get by with for certification by internal and external regulatory authorities“.

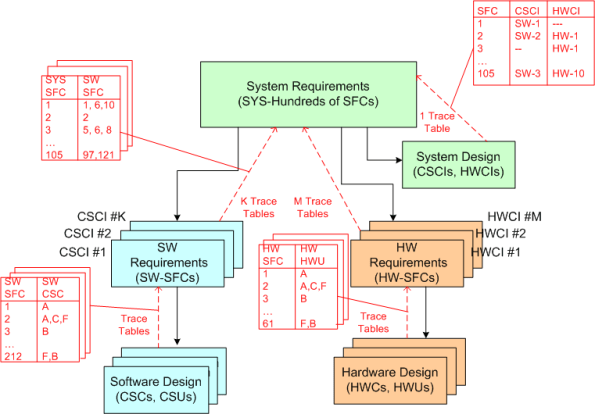

I don’t think companies and teams willfully and maliciously screw up their traceability efforts. It’s just that the pragmatics of diligently maintaining a scrutable traceability structure from ground zero back up into the abstract requirements cloud gets out of hand rather quickly for any system of appreciable size and complexity. The number of parts, types of parts, interconnections between parts, and types of interconnections grows insanely large in the blink of an eye. Manually creating, and more importantly, maintaining, full bottom-to-top traceability evidence in the face of the inevitable change onslaught that’s sure to arise during development becomes a huge problem that nobody seems to openly acknowledge. Thus, “games” are played by both regulators and developers to dance around the reality and pass audits. D’oh!

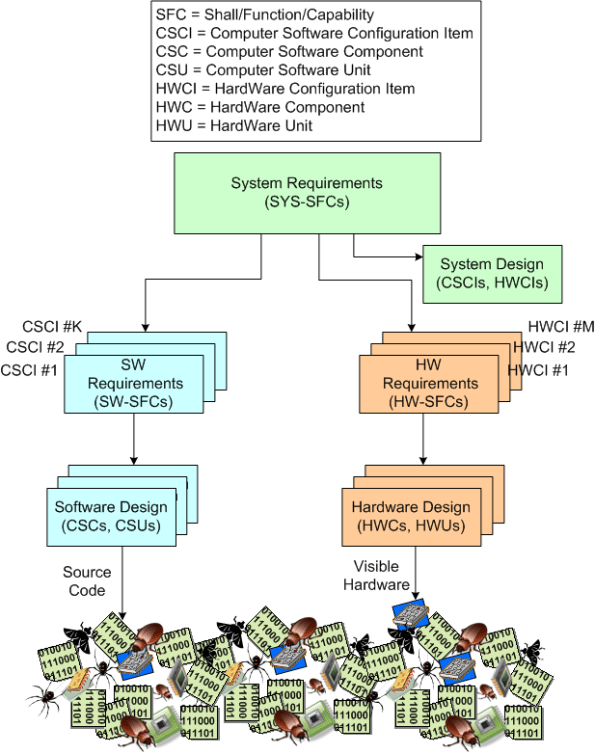

To illustrate the difficulty of the traceability challenge, observe the specification tree below. During the development, the tree (even when agile and iterative feedback loops are included in the process) grows downward and the number of parts that comprise the system explodes.

In “theory” as the tree expands, multiple traceability tables are rigorously created in pay-as-you-go fashion while the info and knowledge and understanding is still fresh in the minds of the developers. When “done” (<- LOL!), an inverse traceability tree with explicit trace tables connecting levels like the example below is supposed to be in place so that any stakeholder can be 100% certain that the hundreds of requirements at the top have been satisfied by the thousands of “cleanly” interconnected parts on the bottom. Uh yeah, right.

Tell Me About The Failures

As the world’s rising population becomes more and more dependent on software to preserve and enhance quality of life, efficiently solving software development problems has become big business. Thus, from the myriad of “agile” flavors to PSP/TSP, there are all kinds of light and heavyweight techniques, methods, and processes available to choose from.

Of course, the people who acquire fame and fortune selling these development process “solutions” seem to only publicize success stories. In each book, case study, lecture, or general article they create to promote their solution, they always cite one or two concrete examples of wild success that “validate” their assertions.

Besides the success stories, I, as a potential consumer of their product, want to hear about the failures. No large scale software development system is perfect and there are always failures, no? But why don’t the promoters expose the failures and the improvements made as a result of the lessons learned from those failures? Humbly providing this information could serve as a competitive differentiator, couldn’t it?

The difference between a methodologist and a terrorist is that you can negotiate with a terrorist – Martin Fowler

Fudge Factors

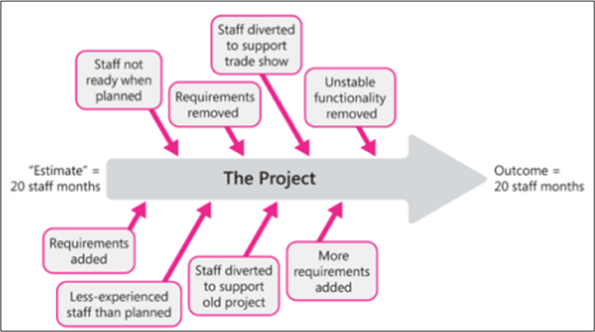

This graphic from Steve McConnell‘s “Software Estimation” shows some of the fudge factors that should be included in project cost estimates. Of course, they never are included, right?

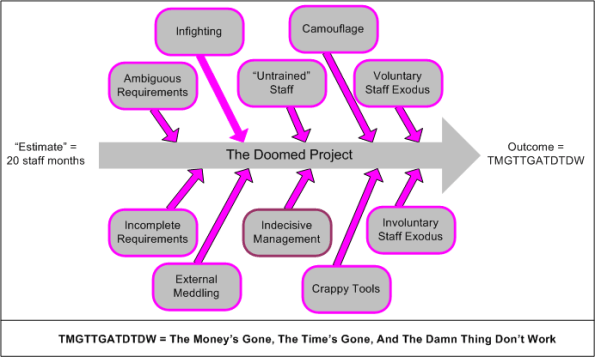

Holy cow, what a coincidence! I happened to stumble upon this mangled version of Mr. McConnell’s graphic somewhere online. D’oh!

Through The Wall

“Break on through to the other side – The Doors

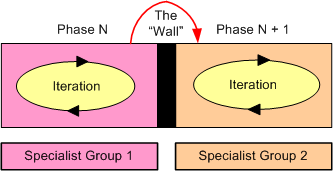

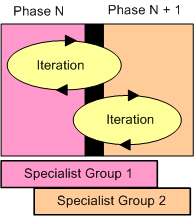

Any project of appreciable size is most likely partitioned into phases where specialists (systems, software, test) that do the work in one phase “hand off” their work products to a new group of specialists in the next phase. One challenge to managing these types of multidisciplinary projects is avoiding the “over the wall” syndrome. You know, the case where the specialist group in phase N chucks their work product over the wall to a previously uninvolved specialist group in phase N+1. Surprise!

One textbook way of attempting to smooth the transitioning of work between groups is by holding an official “review” to serve as a visible waypoint in the project’s trajectory. Done well, a “review” can increase the quality of the work and inter-group relationships. However, done poorly, it is just a self-medicating waste of time where poor work is camouflaged and it serves as a stage for slick talking politicians to increase their stock.

As the figure below illustrates, an alternative to the one-shot, review-based project is the continuous review-based project. The “official” review is still held at a discrete point in time, but since collaborative inter-group communications were initiated well before the review, specialist group 2 will experience fewer “surprises” at review time.

Nevertheless, continuous review-based projects can still fail just as spectacularly as one-shot review-based projects. Can you think of how and why?

What Really Happens…..

Unfathomable Vault

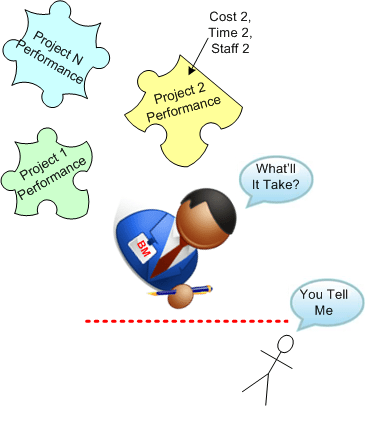

Via work breakdown structures, time cards, and other management tools, most orgs track the time its people spend on projects. Thus, over time, a significant database of historical cost and time data that can be reused to estimate the cost and schedule of future projects gets accumulated. Alas, BD00’s opinion is that most org controllers don’t leverage their treasure troves of information to get reasonable “rev 0” estimates of future efforts. Either :

- they don’t want to know the truth – because they’ll cringe at how much time it really takes to execute an average project

- their tracking systems are so fragmented, un-integrated, and unnavigable that they can’t reuse the info – even if they wanted to

- both 1 and 2 above

It’s ironic how an average org’s controllers demand detailed planning and certainty from their teams but fail to demand the same standards for themselves, no? The next time you’re asked for a project estimate, try retorting with “what does the historical performance data in our unfathomable vault say about similar projects?“. Awe come on, you can do it – even though I can’t 🙂

Obsolete, Or Timeless?

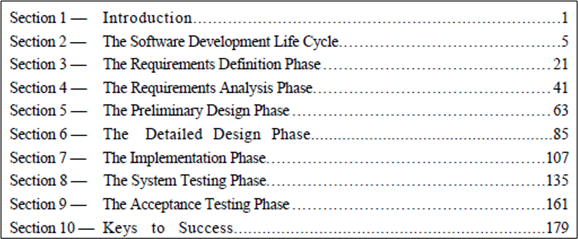

Waaay back in 1992, before “agile” and before all the glorious CMM incarnations and before the highly esteemed “PSP/TSP”, NASA’s Software Engineering Laboratory issued revision #3 of their “Recommended Approach To Software Development“. As you can see below, the table of contents clearly implies a “waterfall” stank to their analysis.

But wait! In section 10 of this well organized and well written “artifact“, the members of the writing team summarize what they think were the keys to successful on time and on budget software project success:

What do you think about this summary? Is the advice outdated and obsolete and applicable only to “waterfall” framed projects? Is the advice timeless wisdom? Are some recommendations obsolete and others timeless nuggets wisdom?

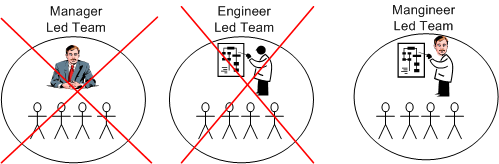

Mangineers And Enginanagers

Expert Number 1 sez:

Engineers don’t make good technical project leaders because they lack business acumen. Thus, they’ll blow the budget and schedule.

Expert Number 2 sez:

Generic managers don’t make good technical project leaders because they don’t understand the work. Thus, they’ll blow the budget and schedule.

Non-expert BD00, who likes to make stuff up and fabricate his own truths, sez:

Yeah, that dilemma sux, but assuming that it can be done, it’s less costly in time and dollars to train an engineer in business skills than it is to train a generic manager in engineering skills.

Of course, if you assume that successful engineer-to-manager or manager-to-engineer cross training is unrealistic (and not many “mainstream” people would fault you for thinking that), then you won’t have to dirty your manicured nails or reach into your pocketbook to, as your fellow managers like to say, “get it done“. The result of this irresponsible, hands off approach is that you will continue to get what you deserve: all of your non-routine, technically challenging development (but not production) projects will blow the budget and schedule more than they normally would if you had put a mangineer or enginanager in charge. Whoo Hoo! Way to go Mr. and Mrs. FOSTMA. Stay the course.