Archive

The Bogus SE/SE Rule

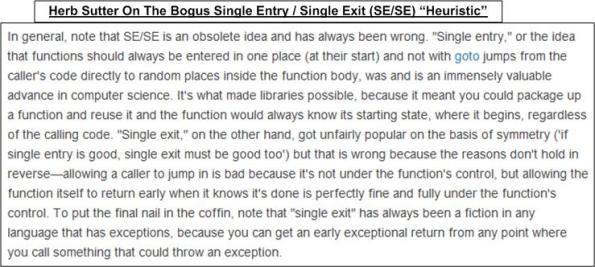

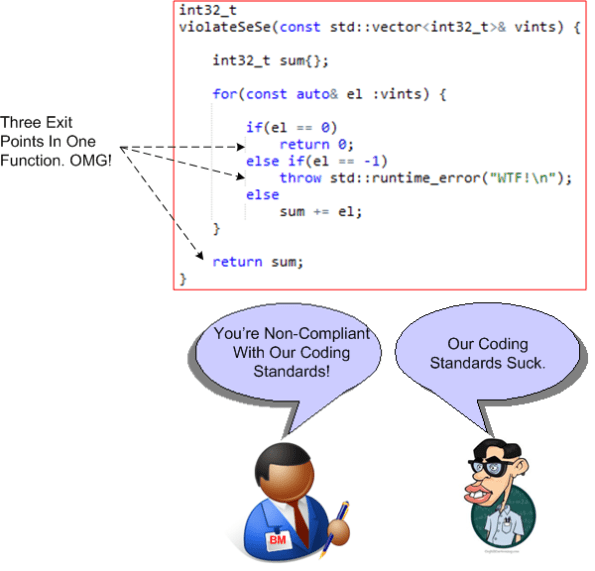

Relatively recently, I participated in a debate with a peer regarding the sacredness of the Single Entry / Single Exit (SE/SE) “rule” of programming. I wish I had this eloquent Herb Sutter treatise on hand when it occurred:

Woot! Now that I’ve stashed the case against SE/SE nazi “enforcement” on this blawg, I’m armed and ready to confront the next brainwashed purist on the matter.

The Point Of No Return

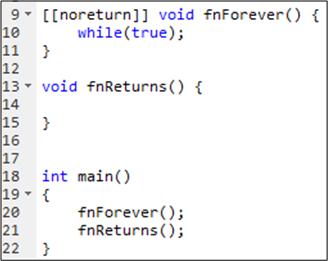

As part of learning the new feature set in C++11, I stumbled upon the weird syntax for the new “attribute” feature: [[ ]]. One of these new C++11 attributes is [[noreturn]].

The [[noreturn]] attribute tells the compiler that the function you are writing will not return control of execution back to its caller – ever. For example, this function will generate a compiler warning or error because even though it returns no value, it does return execution control back to its caller:

The following functions, however, will compile cleanly:

Using [[noreturn]] enables compiler writers to perform optimizations that would otherwise not be available without the attribute. For example, it can silently (but correctly) eliminate the unreachable call to fnReturns() in this snippet:

Note: I used the Coliru interactive online C++ IDE to experiment with the [[noreturn]] attribute. It’s perfect for running quick and dirty learning experiments like this.

The Importance Of Locality

Since I love the programming language he created and I’m a fan of his personal philosophy, I’m always on the lookout for interviews of Bjarne Stroustrup. As far as I can tell, the most recent one is captured here: “An Interview with Bjarne Stroustrup | | InformIT“. Of course, since the new C++11 version of his classic TC++PL book is now available, the interview focuses on the major benefits of the new set of C++11 language features.

For your viewing pleasure and retention in my archives, I’ve clipped some juicy tidbits from the interview and placed them here:

Adding move semantics is a game changer for resource (memory, locks, file handles, threads, and sockets) management. It completes what was started with constructor/destructor pairs. The importance of move semantics is that we can basically eliminate complicated and error-prone explicit use of pointers and new/delete in most code.

TC++PL4 is not simply a list of features. I try hard to show how to use the new features in combination. C++11 is a synthesis that supports more elegant and efficient programming styles.

I do not consider it the job of a programming language to be “secure.” Security is a systems property and a language that is – among other things – a systems programming language cannot provide that by itself.

The repeated failures of languages that did promise security (e.g. Java), demonstrates that C++’s more modest promises are reasonable. Trying to address security problems by having every programmer in every language insert the right run-times checks in the code is expensive and doomed to failure.

Basically, C is not the best subset of C++ to learn first. The “C first” approach forces students to focus on workarounds to compensate for weaknesses and a basic level of language that is too low for much programming.

Every powerful new feature will be overused until programmers settle on a set of effective techniques and find which uses impede maintenance and performance.

I consider Garbage Collection (GC) the last alternative after cleaner, more general, and better localized alternatives to resource management have been exhausted. GC is fundamentally a global memory management scheme. Clever implementations can compensate, but some of us remember too well when 63 processors of a top-end machine were idle when 1 processor cleaned up the garbage for them all. With clusters, multi-cores, NUMA memories, and multi-level caches, systems are getting more distributed and locality is more important than ever.

Agile Software Factories

Freakin’ Oops!

With great power there must also come… great responsibility – Stan Lee

C++, being as sprawling and powerful and flexible as it is, rightly gets dinged for its propensity to bite you in the ass (if you don’t fully understand a language feature you’re trying to use). Thus, many C++ programming book authors point out common “gotchas” while teaching the language to their readers.

The graphic below depicts some “watchout!” snippets from four different, popular C++ programming books. As you might surmise from the picture, my favorite word in a C++ programming book is (freakin’) “Oops!”.

The Ability To Function

While writing the “Rule-Based Safety” post of a few days ago, this quote kept interfering with my thoughts:

Whenever I end up simultaneously holding two opposing ideas in my head, most of the time one of them automatically wins the battle quickly and boots out the loser. Phew, the victory relieves the mental tension. On the down-side, the winner is much too effective at preventing the opposition from ever entering the contemplation chamber again. I hate when that happens.

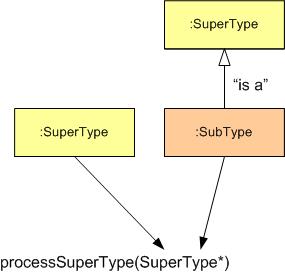

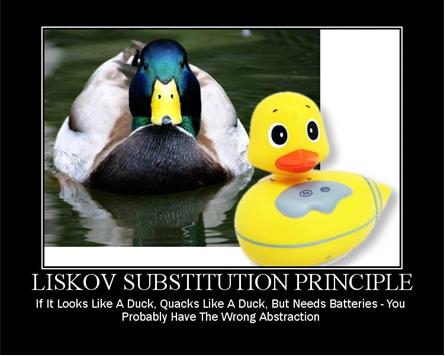

Rule-Based Safety

In this interesting 2006 slide deck, “C++ in safety-critical applications: the JSF++ coding standard“, Bjarne Stroustrup and Kevin Carroll provide the rationale for selecting C++ as the programming language for the JSF (Joint Strike Fighter) jet project:

First, on the language selection:

- “Did not want to translate OO design into language that does not support OO capabilities“.

- “Prospective engineers expressed very little interest in Ada. Ada tool chains were in decline.“

- “C++ satisfied language selection criteria as well as staffing concerns.“

They also articulated the design philosophy behind the set of rules as:

- “Provide “safer” alternatives to known “unsafe” facilities.”

- “Craft rule-set to specifically address undefined behavior.”

- “Ban features with behaviors that are not 100% predictable (from a performance perspective).”

Note that because of the last bullet, post-initialization dynamic memory allocation (using new/delete) and exception handling (using throw/try/catch) were verboten.

Interestingly, Bjarne and Kevin also flipped the coin and exposed the weaknesses of language subsetting:

What they didn’t discuss in the slide deck was whether the strengths of imposing a large coding standard on a development team outweigh the nasty weaknesses above. I suspect it was because the decision to impose a coding standard was already a done deal.

Much as we don’t want to admit it, it all comes down to economics. How much is the lowering of the risk of loss of life worth? No rule set can ever guarantee 100% safety. Like trying to move from 8 nines of availability to 9 nines, the financial and schedule costs in trying to achieve a Utopian “certainty” of safety start exploding exponentially. To add insult to injury, there is always tremendous business pressure to deliver ASAP and, thus, unconsciously cut corners like jettisoning corner-case system-level testing and fixing hundreds of “annoying” rules violations.

Does anyone have any data on whether imposing a strict coding standard actually increases the safety of a system? Better yet, is there any data that indicates imposing a standard actually decreases the safety of a system? I doubt that either of these questions can be answered with any unbiased data. We’ll just continue on auto-believing that the answer to the first question is yes because it’s supposed to be self-evident.

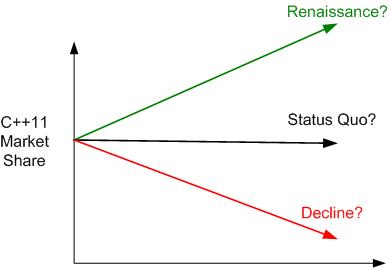

The Renaissance That Wasn’t

In the thoughtful and well-written article, “The Rise and Fall of Languages in 2012”, Andrew Binstock rightly noted that the C++ renaissance predicted by C++ ISO committee chairman Herb Sutter did not materialize last year. Even though C++ butters my bread and I’m a huge Sutter fan, I have to agree with Mr. Binstock’s assessment:

In fact, I can find no evidence that C++ is breaking into new niches at a pace that will affect the language’s overall numbers. For that to happen, it would need to emerge as a primary language in one of today’s busiest sectors: mobile, or the cloud, or big data. Time will tell, but I feel comfortable projecting that C++ will continue to grow in its traditional niches and will advance at the same rate as those niches grow.

Nevertheless, if you buy into Herb’s prognostication that power consumption and computing efficiency (performance per watt) will overtake programmer productivity as the largest business cost drag in the future, then the C++ renaissance may still be forthcoming. Getting 2X the battery life out of a mobile gadget or a .5X reduction in the cost to run a data center may be the economic ticket that triggers a deeper C++ penetration into what Andrew says are today’s busiest sectors: mobile, the cloud, and big data. However, if the C++ renaissance does occur, it won’t take hold overnight, let alone over the one year that has passed since the C++11 standard was hatched.

It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future – Yogi Berra

Milliseconds Since The Epoch 2

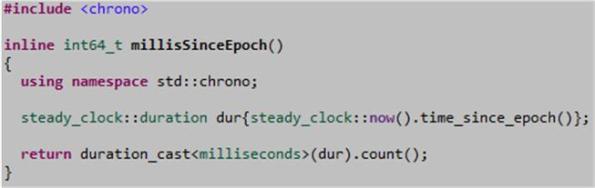

Over a year ago, I hoisted some C++ code on the “Milliseconds Since The Epoch” post for those who were looking for a way to generate timestamps for message tagging and/or event logging and/or code performance measurements. That code was based on the Boost.Date_Time library. However, with the addition of the <chrono> library to C++11, the code to generate millisecond (or microsecond or nanosecond) precision timestamps is not only simpler, it’s now standard:

Here’s how it works:

- steady_clock::now() returns a timepoint object relative to the epoch of the steady_clock (which may or may not be the same as the Unix epoch of 1/1/1970).

- steady_clock::timepoint::time_since_epoch() returns a steady_clock::duration object that contains the number of tick-counts that have elapsed between the epoch and the occurrence of the “now” timepoint.

- The duration_cast<T> function template converts the steady_clock::duration tick-counts from whatever internal time units they represent (e.g. seconds, microseconds, nanoseconds, etc) into time units of milliseconds. The millisecond count is then retrieved and returned to the caller via the duration::count() function.

I concocted this code from the excellent tutorial on clocks/timepoints/durations in Nicolai Josuttis’s “The Standard C++ Library (2nd Edition)“. Specifically, “5.7. Clocks and Timers“.

The C++11 standard library provides three clocks:

- system_clock

- high_resolution_clock

- steady_clock

I used the steady_clock in the code because it’s the only clock that’s guaranteed to never be “adjusted” by some external system action (user change, NTP update). Thus, the timepoints obtained from it via the now() member function never decrease as real-time marches forward.

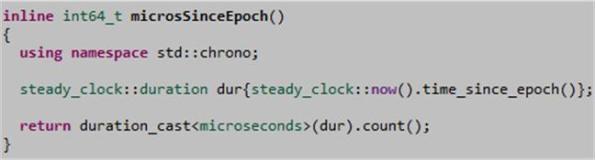

Note: If you need microsecond resolution timestamps, here’s the equivalent code:

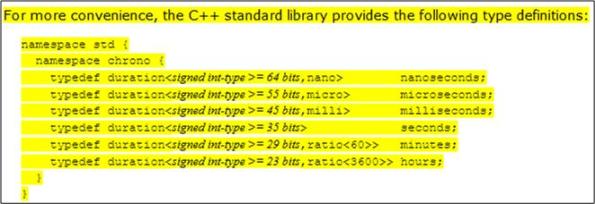

So, what about “rollover“, you ask. As the highlight below from Nicolai’s book shows, the number of bits required by C++11 library implementers increases with increased resolution. Assuming each clock ticks along relative to the Unix epoch time, rollover won’t occur for a very, very, very, very long time; no matter which resolution you use.

Of course, the “real” resolution you actually get depends on the underlying hardware of your platform. Nicolai provides source code to discover what these real, platform-specific resolutions and epochs are for each of the three C++11 clock types. Buy the book if you want to build and run that code on your hardware.