Archive

Close Spatial Proximity

Even on software development projects with agreed-to coding rules, it’s hard to (and often painful to all parties) “enforce” the rules. This is especially true if the rules cover superficial items like indenting, brace alignment, comment frequency/formatting, variable/method name letter capitalization/underscoring. IMHO, programmers are smart enough to not get obstructed from doing their jobs when trivial, finely grained rules like those are violated. It (rightly) pisses them off if they are forced to waste time on minutiae dictated by software “leads” that don’t write any code and (especially) former programmers who’ve been promoted to bureaucratic stooges.

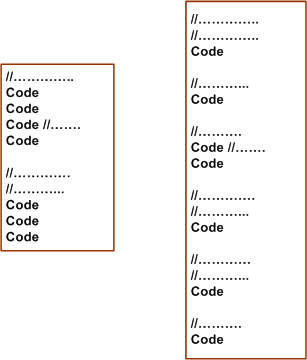

Take the example below. The segment on the right reflects (almost) correct conformance to the commenting rule “every line in a class declaration shall be prefaced with one or more comment lines”. A stricter version of the rule may be “every line in a class declaration shall be prefaced with one or more Doxygenated comment lines”.

Obviously, the code on the left violates the example commenting rule – but is it less understandable and maintainable than the code on the right? The result of diligently applying the “rule” can be interpreted as fragmenting/dispersing the code and rendering it less understandable than the sparser commented code on the left. Personally, I like to see necessarily cohesive code lines in close spatial proximity to each other. It’s simply easier for me to understand the local picture and the essence of what makes the code cohesive.

Even if you insert an automated tool into your process that explicitly nags about coding rule violations, forcing a programmer to conform to standards that he/she thinks are a waste of time can cause the counterproductive results of subversive, passive-aggressive behavior to appear in other, more important, areas of the project. So, if you’re a software lead crafting some coding rules to dump on your “team”, beware of the level of granularity that you specify your coding rules. Better yet, don’t call them rules. Call them guidelines to show that you respect and trust your team mates.

If you’re a software lead that doesn’t write code anymore because it’s “beneath” you or a bureaucrat who doesn’t write code but who does write corpo level coding rules, this post probably went right over your head.

Note: For an example of a minimal set of C++ coding guidelines (except in rare cases, I don’t like to use the word “rule”) that I personally try to stick to, check this post out: project-specific coding guidelines.

Skill Acquisition

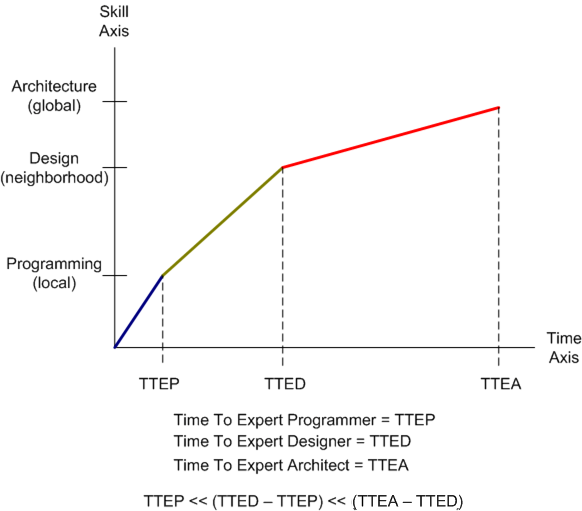

Check out the graph below. It is a totally made up (cuz I like to make things up) fabrication of the relationship between software skill acquisition and time (tic-toc, tic-toc). The y-axis “models” a simplistic three skill breakdown of technical software skills: programming (in-the-very-small) , design (in-the-small) and architecture (in-the-large). The x-axis depicts time and the slopes of the line segments are intended to convey the qualitative level of difficulty in transitioning from one area of expertise into the next higher one in the perceived value-added chain. Notice that the slopes decrease with each transition; which indicates that it’s tougher to achieve the next level of expertise than it was to achieve the previous level of expertise.

The reason I assert that moving from level N to level N+1 takes longer than moving from N-1 to N is because of the difficulty human beings have dealing with abstraction. The more concrete an idea, action or thought is, the easier it is to learn and apply. It’s as simple as that.

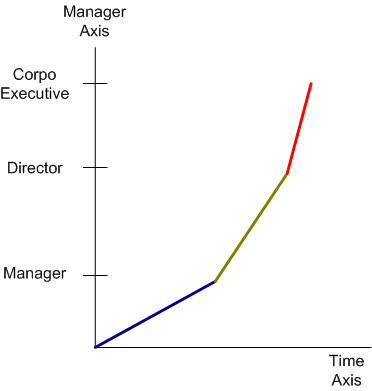

The figure below shows another made up management skill acquisition graph. Note that unlike the technical skill acquisition graph, the slopes decrease with each transition. This trend indicates that it’s easier to achieve the next level of expertise than it was to achieve the previous level of expertise. Note that even though the N+1 level skills are allegedly easier to acquire over time than the Nth level skill set, securing the next level title is not. That’s because fewer openings become available as the management ladder is ascended through whatever means available; true merit or impeccable image.

Error Acknowledgement: I forgot to add a notch with the label DIC at the lower left corner of the graph where T=0.

Strongly Typed

In “Hackers and Painters“, one of my favorite essayists and modern day renaissance men, Paul Graham, states his disdain for strongly typed programming languages. The main reason is that he doesn’t like to be scolded by mindless compilers that handcuff his creativity by enforcing static type-checking rules. Being a C++ programmer, even though I love Paul and understand his point of view, I have to disagree. One of the reasons I like working in C++ is because of the language’s strong type checking rules, which are enforced on the source code during compilation. C++ compilers find and flag a lot of my programming mistakes prior to runtime <- where finding sources of error can be much more time consuming and frustrating.

Driven by “a fierce determination not to impose a specific one size fits all programming style” on programmers, Bjarne Stroustrup designed C++ to allow programmers to override the built-in type system if they consciously want to do so. By preserving the old C style casting syntax and introducing new, ugly C++ casting keywords (static_cast, dynamic_cast, etc) that purposefully make manual casts stick out like a sore thumb and easily findable in the code base, a programmer can legally subvert the type system.

C++ gets trashed a lot by other programming language zealots because it’s a powerful tool with a rich set of features and it supports multiple programming styles (procedural, abstract data types, object-oriented, generic) instead of just one “pure” style. Those attributes, along with Bjarne’s empathy with the common programmer, are exactly why I love using C++. How about you, what language(s) do and don’t you like? Why?

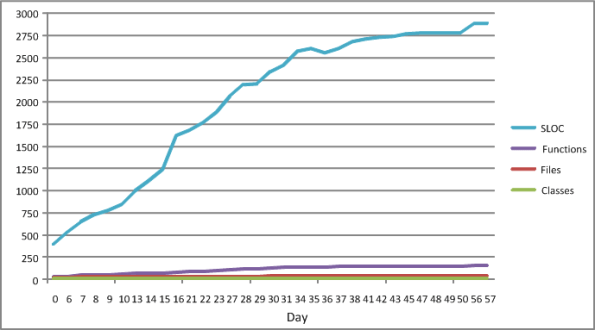

My Velocity

The figure below shows some source code level metrics that I collected on my last C++ programming project. I only collected them because the process was low ceremony, simple, and unobtrusive. I ran the source code tree through an easy to use metrics tool on a daily basis. The plots in the figure show the sequential growth in:

- The number of Source Lines Of Code (SLOC)

- The number of classes

- The number of class methods (functions)

- The number of source code files

So Whoopee. I kept track of metrics during the 60 day construction phase of this project. The question is: “How can a graph like this help me improve my personal software development process?”.

The slope of the SLOC curve, which measured my velocity throughout the duration, doesn’t tell me anything my intution can’t deduce. For the first 30 days, my velocity was relatively constant as I coded, unit tested, and integrated my way toward the finished program. Whoopee. During the last 30 days, my velocity essentially went to zero as I ran end-to-end system tests (which were designed and documented before the construction phase, BTW) and refactored my way to the end game. Whoopee. Did I need a plot to tell me this?

I’ll assert that the pattern in the plot will be unspectacularly similar for each project I undertake in the future. Depending on the nature/complexity/size of the application functionality that will need to be implemented, only the “tilt” and the time length will be different. Nevertheless, I can foresee a historical collection of these graphs being used to predict better future cost estimates, but not being used much to help me improve my personal “process”.

What’s not represented in the graph is a metric that captures the first 60 days of problem analysis and high level design effort that I did during the front end. OMG! Did I use the dreaded waterfall methodology? Shame on me.

Metrics Dilemma

“Not everything that counts can be counted. Not everything that can be counted counts.” – Albert Einstein.

When I started my current programming project, I decided to track and publicly record (via the internal company Wiki) the program’s source code growth. The list below shows the historical rise in SLOC (Source Lines Of Code) up until 10/08/09.

10/08/09: Files= 33, Classes=12, funcs=96, Lines Code=1890

10/07/09: Files= 31, Classes=12, funcs=89, Lines Code=1774

10/06/09: Files= 33, Classes=14, funcs=86, Lines Code=1683

10/01/09: Files= 33, Classes=14, funcs=83, Lines Code=1627

09/30/09: Files= 31, Classes=14, funcs=74, Lines Code=1240

09/29/09: Files= 28, Classes=13, funcs=67, Lines Code=1112

09/28/09: Files= 28, Classes=13, funcs=66, Lines Code=1004

09/25/09: Files= 28, Classes=14, funcs=57, Lines Code=847

09/24/09: Files= 28, Classes=14, funcs=53, Lines Code=780

09/23/09: Files= 28, Classes=14, funcs=50, Lines Code=728

09/22/09: Files= 28, Classes=14, funcs=48, Lines Code=652

09/21/09: Files= 26, Classes=10, funcs=35, Lines Code=536

09/15/09: Files= 26, Classes=10, funcs=29, Lines Code=398

The fact that I know that I’m tracking and publicizing SLOC growth is having a strange and negative effect on the way that I’m writing the code. As I iteratively add code, test it, and reflect on its low level physical design, I’m finding that I’m resisting the desire to remove code that I discover (after-the-fact) is not needed. I’m also tending to suppress the desire to replace unnecessarily bloated code blocks with more efficient segments comprised of fewer lines of code.

Hmm, so what’s happening here? I think that my subconscious mind is telling me two things:

- A drop in SLOC size from one day to the next is a bad thing – it could be perceived by corpo STSJs (Status Takers and Schedule Jockeys) as negative progress.

- If I spend time refactoring the existing code to enhance future maintainability and reduce size, it’ll put me behind schedule because that time could be better spent adding new code.

The moral of this story is that the “best practice” of tracking metrics, like everything in life, has two sides.

No BS, From BS

You certainly know what the first occurrence of “BS” in the title of this blarticle means, but the second occurrence stands for “Bjarne Stroustrup”. BS, the second one of course, is the original creator of the C++ programming language and one of my “mentors from afar” (it’s a good idea to latch on to mentors from afar because unless your extremely lucky, there’s a paucity of mentors “a-near”).

I just finished reading “The Design And Evolution of C++” by BS. If you do a lot C++ programming, then this book is a must read. BS gives a deeply personal account of the development of the C++ language from the very first time he realized that he needed a new programming tool in 1979, to the start of the formal standardization process in 1994. BS recounts the BS (the first one, of course) that he slogged through, and the thinking processes that he used, while deciding upon which features to include in C++ and which ones to exclude. The technical details and chronology of development of C++ are interesting, but the book is also filled with insightful and sage advice. Here’s a sampling of passages that rang my bell:

“Language design is not just design from first principles, but an art that requires experience, experiments, and sound engineering trade-offs.”

“Many C++ design decisions have their roots in my dislike for forcing people to do things in some particular way. In history, some of the worst disasters have been caused by idealists trying to force people into ‘doing what is good for them'”.

“Had it not been for the insights of members of Bell Labs, the insulation from political nonsense, the design of C++ would have been compromised by fashions, special interest groups and its implementation bogged down in a bureaucratic quagmire.”

“You don’t get a useful language by accepting every feature that makes life better for someone.”

“Theory itself is never sufficient justification for adding or removing a feature.”

“Standardization before genuine experience has been gained is abhorrent.”

“I find it more painful to listen to complaints from users than to listen to complaints from language lawyers.”

“The C++ Programming Language (book) was written with the fierce determination not to preach any particular technique.”

“No programming language can be understood by considering principles and generalizations only; concrete examples are essential. However, looking at the details without an overall picture to fit them into is a way of getting seriously lost.”

For an ivory tower trained Ph.D., BS is pretty down to earth and empathic toward his customers/users, no? Hopefully, you can now understand why the title of this blarticle is what it is.

Final, Not Virtual

When writing C++ code, I used to have the habit of tagging every destructor in every class I wrote as “virtual“. I knew that doing so added memory overhead to each object of a class (for storing a pointer to the vtable), but I did it “just in case” I decided to use a class as a base in the future. I was afraid that If I didn’t designate a class dtor as “virtual” from the get go, I might forget to label it as such if I decided later on I needed to use the class as a base.

I have actually made the above mentioned “inheriting-from-a-class-that-doesn’t-have-a-virtual-dtor” mistake several times before – only to discover my faux pas at runtime during unit testing. However, since C++11 added the “final” keyword to the core language to explicitly prevent unintended class derivation (and/or function overriding), I’ve stopped tagging all my dtors as “virtual“. I now tag all of my newly written classes as “final” from the start. With this new habit, if I later decide to use a “final” class as a base class, my compiler pal will diligently scold me that I can’t inherit from a “final” class. Subsequently, when I remove the “final” tag, it always occurs to me to also change the dtor to “virtual“.

#include <iostream>

class ValueType final {

public:

~ValueType() = default;

};

class BaseType {

public:

virtual ~BaseType() = default;

};

int main() {

using namespace std;

cout << " sizeof ValueType = "

<< sizeof(ValueType) << " bytes" << endl

<< " sizeof BaseType = "

<< sizeof(BaseType) << " bytes" << endl;

}