Archive

Measuring Clock Resolution

The Boost.Date_Time C++ library provides an excellent, platform-independent set of interrelated classes for measuring and tracking times and dates during program operation. It is much more capable and, more importantly, accurate than the standard C++ <ctime> library inherited from C. Since we need to benchmark the average and peak latency for our growing distributed, real-time, system infrastructure running on Linux, Solaris and (maybe) Win32 platforms, I decided to use the Boost.Date_Time functionality to measure the clock resolution on a representative of each platform.

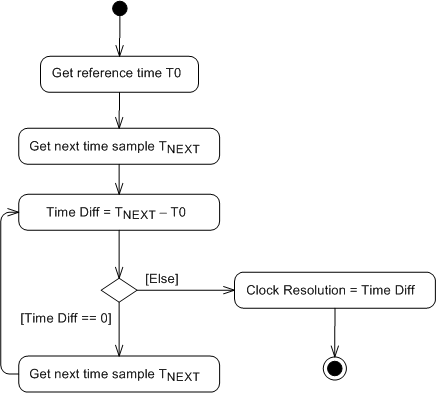

The UML activity diagram below shows the simple algorithm that I used to write a small program that estimates the clock resolution of any compiler-CPU-OS platform combo that Boost.Date_Time is available for. The assumption underlying the design is that the program instructions inside the loop execute an order of magnitude faster than a clock tick increments. At CPU speeds on the order of GHz ( nanoseconds) and clock periods of microseconds, this is a pretty decent assumption, no? The algorithm simply spins around in a tight, high speed loop waiting for the clock to change value relative to an initial reference sample. Note that measuring hardware clock accuracy is another story (Does anyone know if clock hardware accuracy can even be estimated in software?).

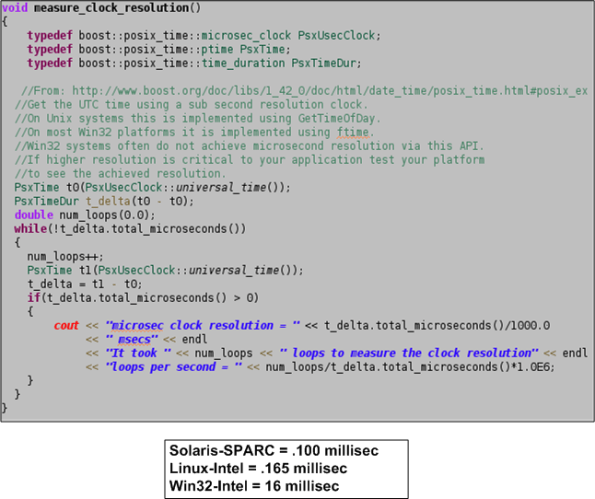

The function below shows the super secret, proprietary, source code that uses the Boost.Date_Time facilities to implement the clock resolution estimation algorithm. Note that the boost microseconds clock, as opposed to the nanoseconds or seconds clock, is used to grab time samples. The seconds clock is too coarse grained for our needs and typical off-the-shelf servers do not provide hardware clocks with nanosecond resolutions without add on circuitry. The box below the code shows the results that I obtained for three platforms on which I ran the program. Of course, the results aren’t perfect (are any results ever perfect?), but since the Solaris and Linux results provide sub-millisecond resolution and we expect end-to-end system latencies on the order of hundreds of milliseconds, the clocks will satisfy our latency measurement needs. Of course, the Win32 result is crappy. Got any thoughts?

Read, Read, Read

To put it mildly, I’m not too fond of software project and “functional” software managers that don’t read code. Even worse, wanna-be-manager tweeners and lofty software “architects” who don’t read code are the pits. Note that I’m not demanding that these exalted ones write code, just actually RTFC (Read The F#@^&*! Code). Why? I thought you’d never ask…..

You see, I’m a believer in the “trust but verify” motto popularized by Ronald Reagan during the cold war. The only pseudo-objective way to truly assess progress, consistency, and quality on a software project is to sample the product – you know, the code. If you know of a better way, then I’m all ears.

It’s not that I don’t trust people to try their best, it’s just that most hierarchical cultures are toxic by unintentional design and that forces people to innocently cover up or camouflage a lack of progress when they fill out their “weekly status sheets” or verbally report progress at useless CYA (Cover Your Arse) meetings. Sadly, once DICs get appointed into elite manager and architect titles, they tend to leave their code reading and (especially) writing days behind. Of course, they’ve arrived (Halleluja!) and they no longer have to do any “janitorial” work that can be done by fungible DORKs.

How about you? Do you think people in the roles of software project manager, software functional manager, and software architect should actively read code as part of their jobs?

In many companies, enterprise architects sit in an ivory tower without doing anything useful. – Ivar Jacobson

An Epic Heavyweight Battle

In this corner, we have Bjarne “No Yarn” Stroustrup, the father of C++. In the other corner, we have James “The Goose” Gosling, the father of Java. Ding, ding…… let’s get ready to ruuuumble!

“No Yarn” comes outs swinging and throws the first haymaker:

Well, the Java designers—and probably the Java marketers even more so—emphasized OO to the point where it became absurd. When Java first appeared, claiming purity and simplicity, I predicted that if it succeeded Java would grow significantly in size and complexity. It did. For example, using casts to convert from Object when getting a value out of a container (e.g., (Apple)c.get(i)) is an absurd consequence of not being able to state what type the objects in the container is supposed have. It’s verbose and inefficient. Now Java has generics, so it’s just a bit slow. Other examples of increased language complexity (helping the programmer) are enumerations, reflection, and inner classes. The simple fact is that complexity will emerge somewhere, if not in the language definition, then in thousands of applications and libraries. Similarly, Java’s obsession with putting every algorithm (operation) into a class leads to absurdities like classes with no data consisting exclusively of static functions. There are reasons why math uses f(x) and f(x,y) rather than x.f(), x.f(y), and (x,y).f()—the latter is an attempt to express the idea of a “truly object-oriented method” of two arguments and to avoid the inherent asymmetry of x.f(y).

In an agile counter move, “The Goose” launches a monstrous left hook:

These days we’re beating the really good C and C++ compilers pretty much always. When you go to the dynamic compiler, you get two advantages when the compiler’s running right at the last moment. One is you know exactly what chipset you’re running on. So many times when people are compiling a piece of C code, they have to compile it to run on kind of the generic x86 architecture. Almost none of the binaries you get are particularly well tuned for any of them. When HotSpot runs, it knows exactly what chipset you’re running on. It knows exactly how the cache works. It knows exactly how the memory hierarchy works. It knows exactly how all the pipeline interlocks work in the CPU. It knows what instruction set extensions this chip has got. It optimizes for precisely what machine you’re on. Then the other half of it is that it actually sees the application as it’s running. It’s able to have statistics that know which things are important. It’s able to inline things that a C compiler could never do. The kind of stuff that gets inlined in the Java world is pretty amazing. Then you tack onto that the way the storage management works with the modern garbage collectors. With a modern garbage collector, storage allocation is extremely fast.

On the age old debate about naked pointers, “The Goose” unleashes a crippling blow to the left kidney:

Pointers in C++ are a disaster. They are just an invitation to errors. It’s not so much the implementation of pointers directly, but it’s the fact that you have to manually take care of garbage, and most importantly that you can cast between pointers and integers—and the way many APIs are set up, you have to!

Enraged, “No Yarn” returns the favor with a rapid jab, jab, jab, uppercut combo:

Well, of course Java has pointers. In fact, just about everything in Java is implicitly a pointer. They just call them references. There are advantages to having pointers implicit as well as disadvantages. Separately, there are advantages to having true local objects (as in C++) as well as disadvantages. C++’s choice to support stack-allocated local variables and true member variables of every type gives nice uniform semantics, supports the notion of value semantics well, gives compact layout and minimal access costs, and is the basis for C++’s support for general resource management. That’s major, and Java’s pervasive and implicit use of pointers (aka references) closes the door to all that.

The “dark side” of having pointers (and C-style arrays) is of course the potential for misuse: buffer overruns, pointers into deleted memory, uninitialized pointers, etc. However, in well-written C++ that is not a major problem. You simply don’t get those problems with pointers and arrays used within abstractions (such as vector, string, map, etc.). Scoped resource management takes care of most needs; smart pointers and specialized handles can be used to deal with most of the rest. People whose experience is primarily C or old-style C++ find this hard to believe, but scope-based resource management is an immensely powerful tool and user-defined types with suitable operations can address classical problems with less code than the old insecure hacks.

Stunned silly, “The Goose” steps back, regroups, and charges back into the fray:

One of the most problematic (situations) over the years in C++ has been multithreading. Multithreading is very tightly designed into the code of Java and the consequence is that Java can deal with multicore machines very, very well.

“The Yarn” stands his ground and attempts to weather the ferocious onslaught:

The very first C++ library (really the very first C with classes) library, provided a lightweight form of concurrency and over the years, hundreds of libraries and frameworks for concurrent, parallel, and distributed computing have been built in C++. C++0x will provide a set of facilities and guarantees that saves programmers from the lowest-level details by providing a “contract” between machine architects and compiler writers—a “machine model.” It will also provide a threads library providing a basic mapping of code to processors. On this basis, other models can be provided by libraries. I would have liked to see some simpler-to-use, higher-level concurrency models supported in the C++0x standard library, but that now appears unlikely. Later—hopefully, soon after C++0x—we will get more libraries specified in a technical report: thread pools and futures, and a library for I/O streams over wide area networks (e.g., TCP/IP). These libraries exist, but not everyone considers them well enough specified for the standard.

And the winner is………?

So, do you think that I’ve served well as an impartial referee for this epic heavyweight battle? Hell, I hope not. I’m strongly biased toward C++ because it’s taken me years of study and diligent practice to become an intermediate-to-advanced C++ programmer (but still well below the skill level of the masters). I think that most Java programmer’s who religiously trash C++ do so out of fear of: its breadth+depth, its suitability for application at all layers of the stack, and the option to “get dangerously close to the machine“. On the other hand, C++ programmers who trash Java do so out of a sense of elitism and a disdain for object oriented purity.

Note: The snippets in this blarticle were copied and pasted from the delightful and engrossing “Masterminds Of Programming“. The book’s author, Federico Biancuzzi, not only picked the best possible people to interview, his questions were insightful and deeply thought provoking.

Imperatively Dysfunctional

I’ve been programming in the C and C++ imperative languages forever. However, it seems that functional languages like Lisp, F#, Erlang, Scheme, Haskell, etc, are generating a lot of buzz these days. Curious as to what all the fuss is about, I tuned into Rebecca Parsons’ “Functional Languages 101” InfoQ video to learn more about these formerly “academic” languages.

OMG! It felt like getting a root canal without novocaine. Since I’m imperatively dysfunctional, I found her lecture to be really tough to follow. The fact that all of Rebecca’s viewgraphs were black and white text-only throwbacks to the 70’s didn’t help – not one conceptual diagram was presented.

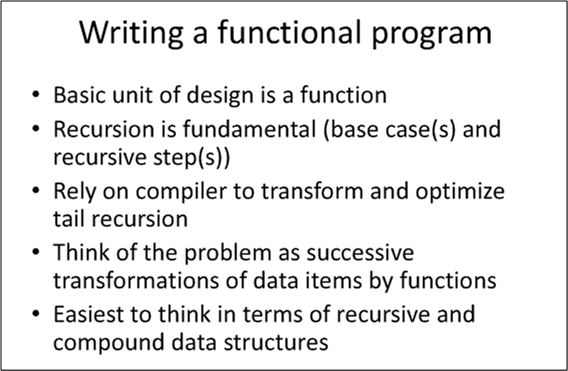

One of Rebecca’s opening foils is shown below. As opposed to a statement, which is the fundamental unit of design in imperative languages, the pure “function” is ground zero in the functional language world. Recursion and statelessness are fundamental tenets of functional languages. Problems, even those that are naturally stateful (most real-world problems?), must be morphed into the vocabulary and semantics of functional language land.

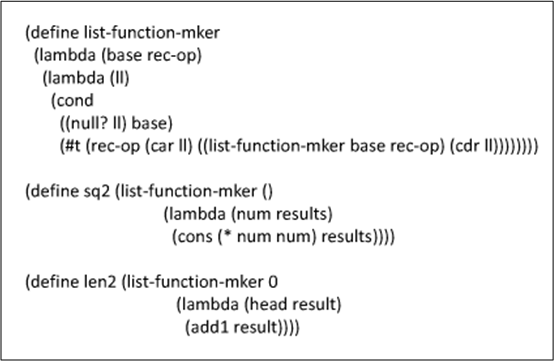

The viewgraph below shows one of several Scheme language listings that Rebecca presented. Even after listening to her explanation of how it works, the only thing about the parentheses encoded gibberish that I grasped is that it defines the logic of three recursive functions that do something. D’oh!

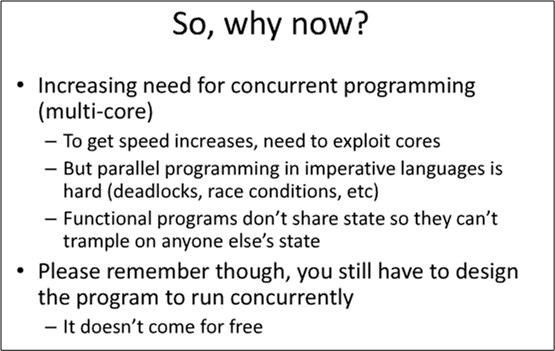

In one of her last viewgraphs (see below), Ms. Parsons addressed the main reason for the rise of functional programming languages. Being a specifier/designer/developer of distributed real-time sensor systems, I’m really keen on her first bullet.

Even though watching Rebecca’s lecture didn’t enlighten me and it made my head spin, I’m going to crack open an Erlang programming book and try to learn more about the subject. Eventually, I just may “get it” and experience the “ah-ha” moment that many others seem to have experienced.

Implicit Type Conversion

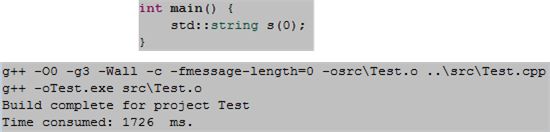

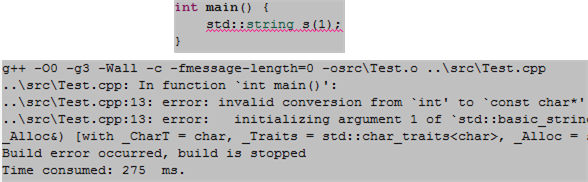

Check out this bit of C++ code and its unexpected, successful compile:

Next, observe the runtime result from the Win Visual Studio 8.0 IDE:

Thirdly, check out this bit of C++ code and its expected, unsuccessful compile:

What’s up wit’ dat? The reason I brought this up is because we’ve discovered that we have this type of bug in our growing 5 figure code base. However, we haven’t been able to locate and kill it – yet.

Note: After being enlightened by a kind and sharing member of a linkedIn.com C++ group, I was told the reason for the successful compile. Since one of the constructors of the base class of std::string takes a char*, the 0 in the s(0) definition is implicitly converted from int(o) to char*(0); the null pointer. In the non-zero case, the compiler rejects the attempt to convert int(1) into char*(1). As this example shows, implicit type conversion, a necessary C++ language feature needed to remain backwardly compatible with C, can be a tricky and subtle source of bugs.

Note: After being enlightened by a kind and sharing member of a linkedIn.com C++ group, I was told the reason for the successful compile. Since one of the constructors of the base class of std::string takes a char*, the 0 in the s(0) definition is implicitly converted from int(o) to char*(0); the null pointer. In the non-zero case, the compiler rejects the attempt to convert int(1) into char*(1). As this example shows, implicit type conversion, a necessary C++ language feature needed to remain backwardly compatible with C, can be a tricky and subtle source of bugs.

XML In UML

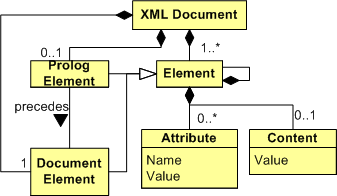

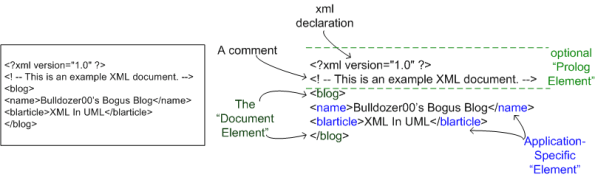

While learning XML, I concocted this UML class diagram of the conceptual structure of XML as a quick look refresher guide:

The diagram can be interpreted as:

- A typical XML document is composed of a “Document Element“, an optional “Prolog Element”, and many application specific “Element” classes.

- Besides a base “Element” class, there are two subclass types: the “Document Element” and the “Prolog Element”.

- In an XML file, the “Prolog Element” (if present) must precede the “Document Element”.

- An element contains content and, optionally, 1 or more “Attributes”.

- Each “Attribute” is comprised of a Name/Value pair.

- An element can also contain other nested elements, providing support for structured data representation.

Here’s a simple concrete example XML file and the mapping from concrete to abstract. Note that the “comment” and “xml declaration” lines aren’t represented in the abstract class diagram model. I left out that second order level of detail to keep the class diagram simple.

Transfer Of Mental Ownership

I don’t know how to write code in the Erlang programming language, but ever since reading Bjarne Stroustrup‘s “The Design And Evolution Of C++“, I’ve been interested in the topic of programming language creation, development, and adoption. Sinisterly, I look for how much support, or lack thereof, that management provided to the language creators.

In this entertaining InfoQ video, “A Discussion Of Basic vs. Applied Research In The Software Domain And The Creation Of Erlang“, kindly and soft-spoken Bjarne Dacker recounts the development of Erlang. Here are some of my distorted notes:

Many problems that need to be solved by software are not computationally intensive, they’re symbolic.

The sequential and synchronous Von Neumann programming model does not map cleanly into the realm of real-time control systems.

The Erlang team asked: “Why are software academics obsessed with all these subtle, disparate, awkward, and complicated communication schemes like buffers, semaphores, mailboxes, rendezvous, regions, pipes? Why not just simply send messages between asynchronously running processes?”

Erlang designers took the goodies from Modula, Ada, and Chill and discarded the baddies.

By being devious and cunning, Dacker was able to subvert the corpo bureaucratic mandate that “everybody shall use the centralized IBM mainframe” and he miraculously secured approval to purchase a dedicated VAX (close to state of the art at the time) computing platform for his team.

Ericsson management wanted Erlang to be proprietary; a secret weapon that would allow them to develop their telecommunication products faster than their competitors. On the other hand, Ericsson management disallowed the usage of Erlang internally because it wasn’t an open standard (LOL!).

You can’t just throw new technology over the wall to product teams. You must create mixed teams; embedding applied researchers within product teams. You must facilitate the transfer of “mental ownership”.

In 2009, “something” happened. The number of Erlang downloads at Erlang.org started to skyrocket.

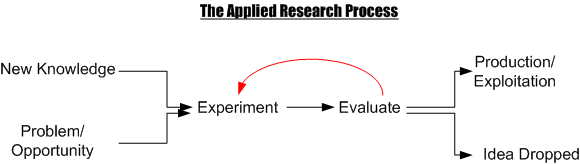

In keeping with my goal of providing a dorky graphic with each blog post, I present Mr. Dacker’s process for the successful transition of applied research knowledge into the marketplace.

Notice that going “backward” and cycling multiple times through the mistake prone experiment/evaluate activities (which most sequential, linear, forward-only management CGHs abhor and forbid) is an integral part of Dacker’s process. The mixing of researchers with product developers occurs in the production/exploitation stage.

Watch Out For Multipletons

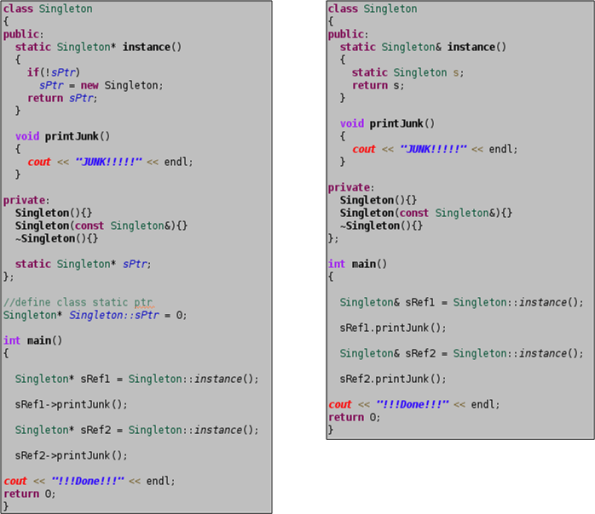

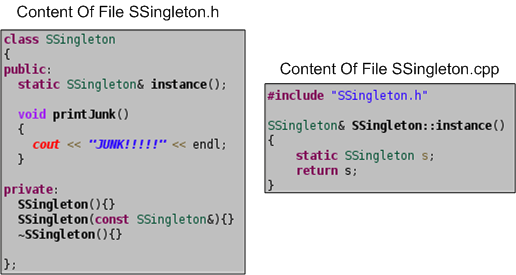

Because C++ has both pointers and references, there are two ways to implement a singleton. The programs below show the difference between the approaches (I know, I know. I could’ve used a smart pointer on the left). Since references can’t be “accidently” deleted by client code, I prefer the reference method on the right. Plus, there’s no need for an “if” test every time the singleton’s handle is retrieved by client code.

When using a singleton, don’t forget to put the definition of the “instance()” member function (or the pointer definition) into a separate .cpp implementation file, and not as an inline in the .h file. Otherwise, each .cpp file in your program that needs to access the singleton will get it’s own personal copy of a singleton, transforming it into a “multipleton”. You’ll get a program that compiles but has a subtle, hard to detect runtime bug that won’t crash the program.

And yes, we found this out the hard way. 🙂

Post-picture insertion notes: 1) I shoulda named the variables in the main() of the pointer version of the singleton sPtr1 and sPtr2. 2). For consistency, I prolly shoulda made the copy assignment operator function private in both implementations. Is there anything else I could do to improve the code?

Accessing Configuration Data

Assume that on initialization, your C++ application reads in a bunch of configuration parameters from secondary storage prior to commencing its runtime mission. Via a trio of simple UML class diagrams, the figure below shows three ways (patterns?) to structure your application to read in and store configuration data for subsequent use by the program‘s productive, value added classes (user1, user2, etc).

In the first design, a singleton class is used to read and store the runtime configuration in RAM. The singleton can either be auto-instantiated at program load time in global/namespace memory before main() executes, or the first time it is accessed by one of the program’s user objects.

In the second approach, you employ a “ConfigOwner” class that encapsulates and owns the configuration data reader class (AppConfig). On program startup, the “ConfigOwner” object instantiates the “AppConfig” reader object and then subsequently passes a reference/pointer to it to all the user objects (which the “ConfigOwner” object doesn’t own).

In the third strategy, a higher level object (AppEncapsulator) owns all other objects in the application. On startup, this parent class is instantiated first. It fully controls the initialization sequence, creating the “AppConfig” object first and then pushing a reference/pointer to it down to its child User class objects when it subsequently constructs them.

Since the application startup sequence is centrally controlled, the third, parent-child approach is totally thread-safe. The implementation of the singleton approach, where the singleton is instantiated at program load time before main() starts executing, is also thread safe. The instantiation-on-first-access singleton approach and the ConfigOwner approach are subtlely thread unsafe without some clever synchronization coding added to ensure that the AppConfig object is fully constructed before it is accessed by its users.

Since I’m not fond of using singletons in situations where they’re not absolutely required (and this is arguably one of those cases, no?) and I disdain “clever” coding, I prefer the last, centrally controlled strategy. How about you? Are you clever, or a simpleton like me?

Note: Don’t mind the bracket turd on the right of the diagram. Since I’m a lazy ass and I try not to be a perfectionist when perfection is not needed, I left the pooper in rather than removing, fixing, and reinserting the graphic into the post. Too much work.

Greenspun’s Tough Love

In Founders At Work, Phil Greenspun recounts his tough-love approach toward molding his young programmers into well-rounded and multi-talented individuals:

For programmers, I had a vision—partly because I had been teaching programmers at MIT—that I didn’t like the way that programmer careers turned out. I wanted them to have a real professional résumé.

They would have to develop the skill of starting from the problem. They would invest some time in writing up their results. I was very careful about trying to encourage these people to have an independent professional reputation, so there’s code that had their name on it and that they took responsibility for, documentation that explained what problem they were trying to solve, what alternatives they considered, what the strengths and limitations of this particular implementation that they were releasing were, maybe a white paper on what lessons they learned from a project. I tried to get the programmers to write, which they didn’t want to do.

People don’t like to write. It’s hard. The people who were really good software engineers were usually great writers; they had tremendous ability to organize their thoughts and communicate. The people who were sort of average-quality programmers and had trouble thinking about the larger picture were the ones who couldn’t write.

So, did it work? Sadly, Phil follows up with:

In the end, the project was a failure because the industry trends moved away from that. People don’t want programmers to be professionals; they want programmers to be cheap. They want them to be using inefficient tools like C and Java. They just want to get them in India and pay as little as possible. But I think part of the hostility of industrial managers toward programmers comes from the fact that programmers never had been professionals.

Programmers have not been professionals because they haven’t really cared about quality. How many programmers have you asked, “Is this the right way to do things? Is this going to be good for the users?” They reply, “I don’t know and I don’t care. I get paid, I have my cubicle, and the air-conditioning is set at the right temperature. I’m happy as long as the paycheck comes in.”

FAW was published in 2008. Two years later, do you think attitudes have changed much? What’s your attitude?