Archive

Dream, Mess, Catastrophe

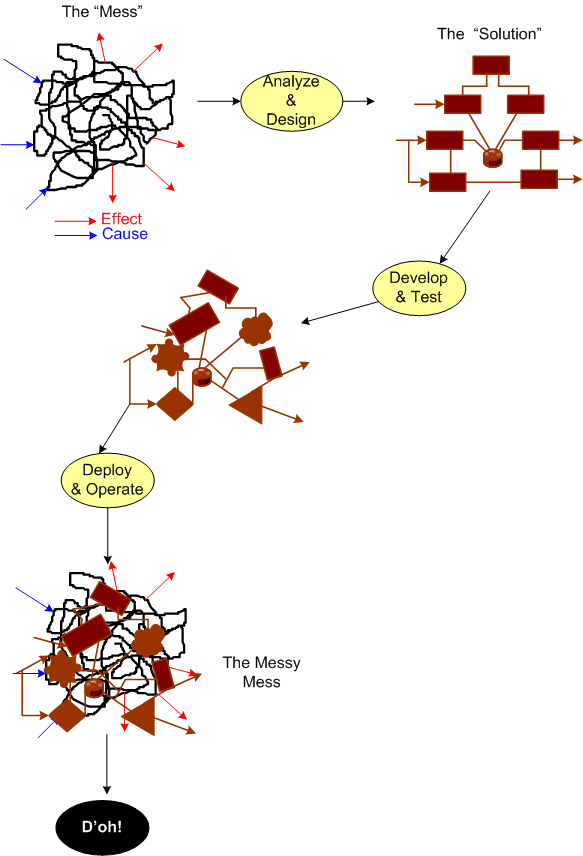

To build high quality, successful, long-lived, “Big” software, you must design it in terms of layers (that’s why the ISO ISO model for network architecture has 7, crisply defined layers). If you don’t leverage the tool of layering (and its close cousin – leveling) in an attempt to manage complexity, then: your baby won’t have much conceptual integrity; you’ll go insane; and you’ll be the unproud owner of a big ball of mud that sucks down maintenance funds like a Dyson and may crumble to pieces at the slightest provocation. D’oh!

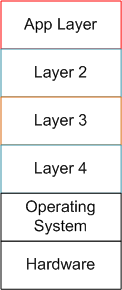

The figure below shows a reference model for a layered application. Note that even though we have a neat stack, we can’t tell if we have a winner on our hands.

By adding the inter-layer dependencies to the reference architecture, the true character of our software system will be revealed:

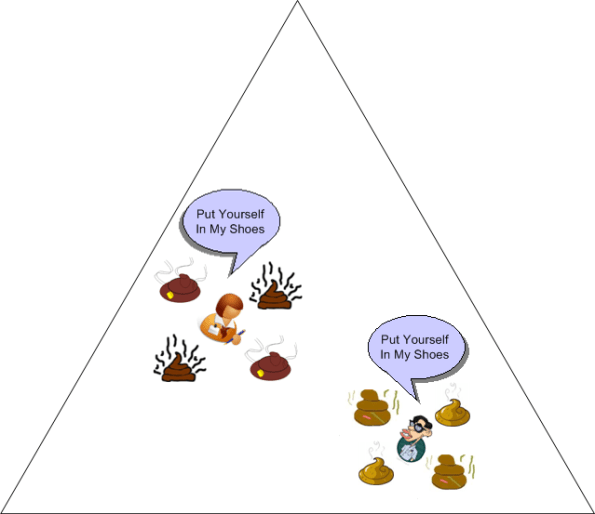

In the “Maintenance Dream“, the inter-layer APIs are crisply defined and empathetically exposed in the form a well documented interfaces, abstractions, and code examples. The programmer(s) of a given layer only have to know what they have to provide to the users above them and what the next layer below lovingly provides to them. Ah, life is good.

Next, shuffle on over to the “Maintenance Mess“. Here, we have crisply defined layers, but the allocation of functionality to the layers has been hosed up ( a violation of the principle of “leveling“) and there’s a beast in the making. Thus, in order for App Layer programmers to be productive, they have to stuff their head with knowledge/understanding of all the sub-layer APIs to get their jobs done. Hopefully, their heads don’t explode and they don’t run for the exits.

Finally, skip on over to the (shhh!) “Maintenance Catastrophe“. Here, we have both a leveling mess and an incoherent set of incomprehensible (to mere mortals) inter-layer APIs. In the worst case: the layers aren’t discernible from one another; it takes “forever” to on-board new project members; it takes forever to fix bugs; it takes forever to add features; and it takes an heroic effort to keep the abomination alive and kicking. Double D’oh!

Forever == Lots Of Cash

In orgs that have only ever created “Maintenance Messes and Catastrophies“, since they’ve never experienced a “Maintenance Dream“, they think that high maintenance costs, busted schedules, and buggy releases are the norm. How do you explain the color green to someone who’s spent his/her whole life immersed in a world of red?

Customer Suffering

For some context, assume that your software-intensive system can actually be modeled in terms of “identifiable C”s:

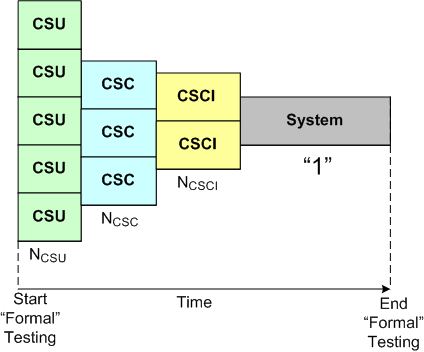

Given this decomposition of structure, the ideal but pragmatically unattainable test plan that “may” lead to success is given by:

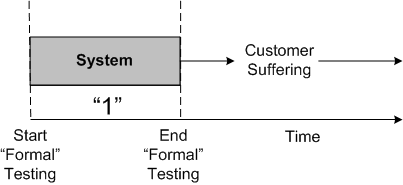

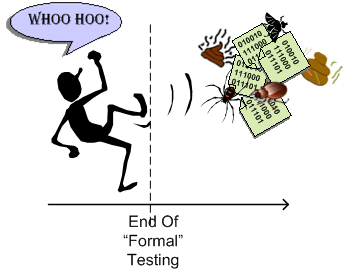

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the test plan that virtually guarantees downstream failure is given by:

In practice, no program/project/product/software leader in their right mind skips testing at all the “C” levels of granularity. Instead, many are forced (by the ubiquitous “system” they’re ensconced in) to “fake it” because by the time the project progresses to the “Start Formal Testing” point, the schedule and budget have been blown to bits and punting the quagmire out the door becomes the top priority.

From Within, From Without

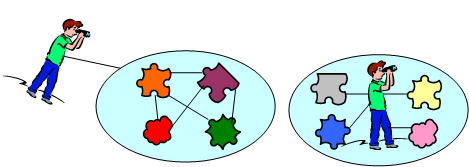

With exceptions (and there are always exceptions) everyone knows that the view “from within” is different than the view “from without“.

While viewing “from without“, there is typically less emotional attachment of the viewer to the viewed. The more one is attached to the view “from within“, the more difficult it is to extricate oneself from that view and form a secondary view “from without“.

On product development projects, it’s much easier for a project team member to step outside of the intricate details “from within” to form a view “from without” than it is for an “outsider” to form a view “from within“. But just because it’s easier, it doesn’t mean that it’s done often.

This “from within” and “from without” crap is simply a twist on the old “put yourself in someone else’s shoes” advice…..

Messy Mess

A Bunch Of STIFs

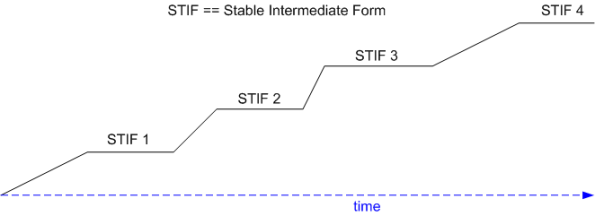

Grady Booch states that good software architectures evolve incrementally via a progressive sequence of STable Intermediat Forms (STIFs). At each point of equilibrium, the “released” STIF is exercised by an independent group of external customers and/or internal testers. Defects, unneeded functionality, missing functionality, and unmet “ilities” are ferreted out and corrected early and often.

The alternative to a series of STIFs is the ubiquitous, one-shot, Unstable Fuming Fiasco (UFF):

Note: After I converted this draft post into a publishable one and queued it up, I experienced a sense of deja-vu. As a consequence, I searched back through my draft (91) and published (987) post lists. I found this one. D’oh! and LOL! I’m sure I’ve repeated myself many times during my blogging “career“, but hey, a steady drumbeat is more effective than a single cymbal crash. No?

Note: After I converted this draft post into a publishable one and queued it up, I experienced a sense of deja-vu. As a consequence, I searched back through my draft (91) and published (987) post lists. I found this one. D’oh! and LOL! I’m sure I’ve repeated myself many times during my blogging “career“, but hey, a steady drumbeat is more effective than a single cymbal crash. No?

Levels Of Testing

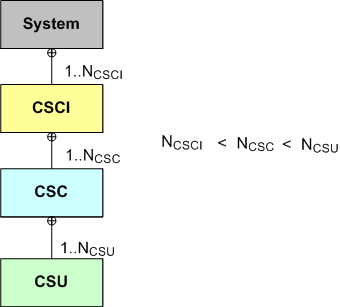

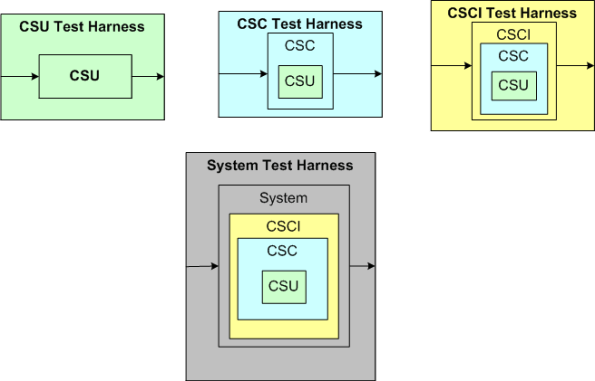

Using three equivalent UML class diagrams, the graphic below conveys how to represent a system design using the “C” terminology of the aerospace and defense industry. On the left, the system “contains” CSCIs and CSCIs contain CSCs, etc. In the middle, the system “has” CSCIs. On the right, CSCIs “reside within” the system.

Leaving aside the question of “what the hell’s a unit“, let’s explore four “levels of testing” with the aid of the multi-graphic below that uses the “reside within” model.

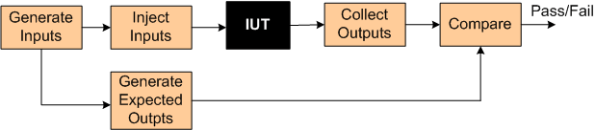

In order to test at any given level, some sort of test harness is required for that level. The test harness “system” is required to:

- generate inputs (for a CSU, CSC, CSCI, or the system),

- inject the inputs into the “Item Under Test” (CSU, CSC, or CSCI),

- collect the actual outputs from the IUT,

- compare the actual outputs with expected outputs.

- declare success or failure for each test

When planning a project up front, it’s easy to issue the mandate: “we’ll formally test and document at all four levels; progressing from the bottom CSU level up to the system level“. However, during project execution, it’s tough to follow “the plan” when the schedule starts to, uh, expand, and pressure mounts to “just shipt it, damn it!“.

Because:

- the number of IUTs in a level decreases as one moves up the ladder of abstraction (there’s only a single IUT at the top – the system),

- the (larger and fewer) IUTs at a given level are richer in complex behavior than the (smaller and more plentiful) IUTs at the next lowest level,

- it is expensive to develop high fidelity, manual and/or automated test harnesses for each and every level

- others?

there’s often a legitimate ROI-based reason to eschew all levels of formal testing except at the system level. That can be OK as long as it’s understood that defects found during final system level testing will be more difficult and time consuming ($$$) to localize and repair than if lower levels of isolated testing had been performed prior to system testing.

To mitigate the risk of increased time to localize/repair from skipping levels of testing, developers can build in test visibility points that can be turned on/off during operation.

The tradeoff here is that designing in an extensive set of runtime controllable test points adds complexity, code, and additional CPU/memory loading to both the system and test harness software. To top it off, test point activation is often needed most when the system is being stressed with capacity test scenarios where the nastiest of bugs tend surface – but the additional CPU and memory load imposed on the system/harness may itself cause tests to fail and mutate bugs into looking like they are located where they are not. D’oh! Ain’t life a be-otch?

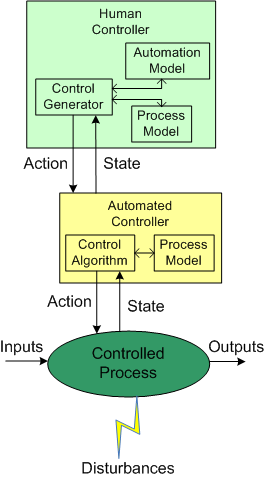

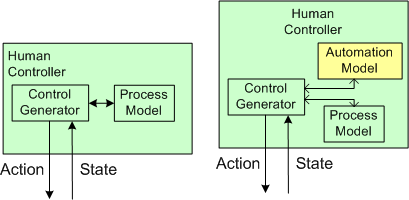

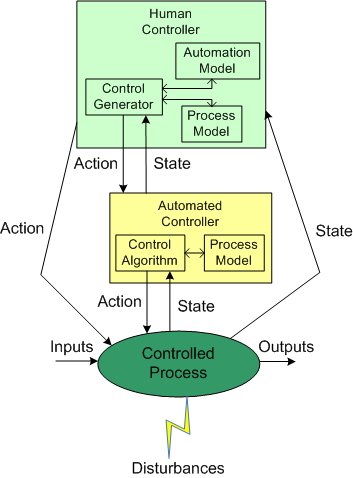

Human And Automated Controllers

Note: The figures that follow were adapted from Nancy Leveson‘s “Engineering A Safer World“.

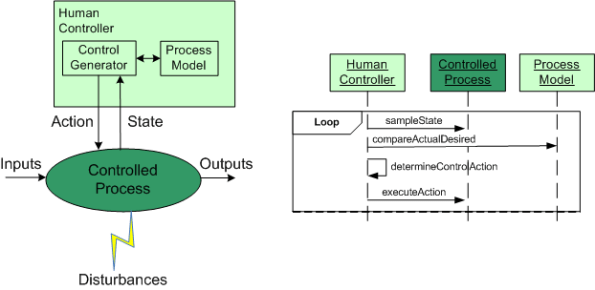

In the good ole days, before the integration of fast (but dumbass) computers into controlled-process systems, humans had no choice but to exercise direct control over processes that produced some kind of needed/wanted results. During operation, one or more human controllers would keep the “controlled process” on track via the following monitor-decide-execute cycle:

- monitor the values of key state variables (via gauges, meters, speakers, etc)

- decide what actions, if any, to take to maintain the system in a productive state

- execute those actions (open/close valves, turn cranks, press buttons, flip switches, etc)

As the figure below shows, in order to generate effective control actions, the human controller had to maintain an understanding of the process goals and operation in a mental model stored in his/her head.

With the advent of computers, the complexity of systems that could be, were, and continue to be built has skyrocketed. Because of the rise in the cognitive burden imposed on humans to effectively control these newfangled systems, computers were inserted into the control loop to: (supposedly) reduce cognitive demands on the human controller, increase the speed of taking action, and reduce errors in control judgment.

The figure below shows the insertion of a computer into the control loop. Notice that the human is now one step removed from the value producing process.

Also note that the human overseer must now cognitively maintain two mental models of operation in his/her head: one for the physical process and one for the (supposedly) subservient automated controller:

Assuming that the automated controller unburdens the human controller from many mundane and high speed monitoring/control functions, then the reduction in overall complexity of the human’s mental process model may more than offset the addition of the requirement to maintain and understand the second mental model of how the automated controller works.

Since computers are nothing more than fast idiots with fixed control algorithms designed by fallible human experts (who nonetheless often think they’re infallible in their domain), they can’t issue effective control actions in disturbance situations that were unforeseen during design. Also, due to design flaws in the hardware or software, automated controllers may present an inaccurate picture of the process state, or fail outright while the controlled process keeps merrily chugging along producing results.

To compensate for these potentially dangerous shortfalls, the safest system designs provide backup state monitoring sensors and control actuators that give the human controller the option to override the “fast idiot“. The human controller relies primarily on the interface provided by the computer for monitoring/control, and secondarily on the direct interface couplings to the process.

Butt The Schedule

Did you ever work on a project where you thought (or knew) the schedule was pulled out of someone’s golden butt? Unlucky you, cuz Bulldozer00 never has.

Maintenance Cycles And Teams

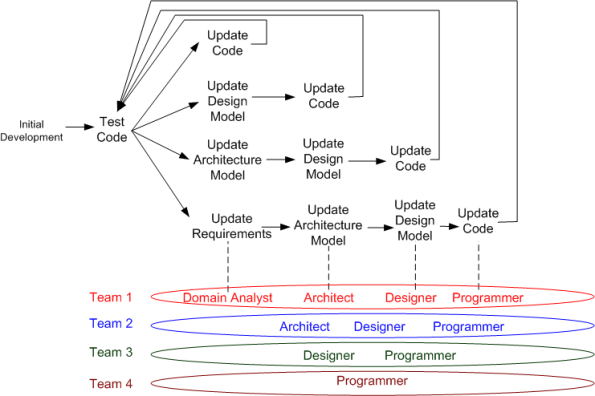

The figure below highlights the unglamorous maintenance cycle of a typical “develop-deliver-maintain” software product development process. Depending on the breadth of impact of a discovered defect or product enhancement, one of 4 feedback loops “should” be traversed.

In the simplest defect/enhancement case, the code is the only product artifact that must be updated and tested. In the most complex case, the requirements, architecture, design, and code artifacts all “should” be updated.

Of course, if all you have is code, or code plus bloated, superficial, write-once-read-never documents, then the choice is simple – update only the code. In the first case, since you have no docs, you can’t update them. In the second case, since your docs suck, why waste time and money updating them?

After the super-glorious business acquisition phase and during the mini-glorious “initial development” phase, the team is usually (but not always – especially in DYSCOs and CLORGs) staffed with the roles of domain analyst(s), architect(s), designer(s), and programmer(s). Once the product transitions into the yukky maintenance phase, the team may be scaled back and roles reassigned to other projects to cut costs. In the best case, all roles are retained at some level of budgeting – even if the total number of people is decreased. In the worst case, only the programmer(s) are kept on board. In the suicidal case, all roles but the programmer(s) are reassigned, but multiple manager type roles are added. (D’oh!)

Note that there does not have to be a one to one correspondence between a role and a person; one person can assume multiple roles. Unfortunately, the staff allocation, employee development, and reward systems in most orgs aren’t “designed” to catalyze and develop the added value of multi-role-capable people. That’s called the “employee-in-a-box” syndrome.

Capers And Salmon

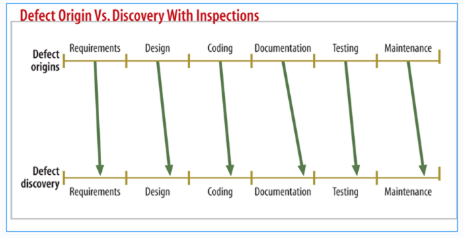

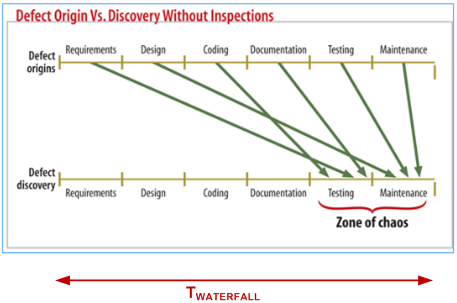

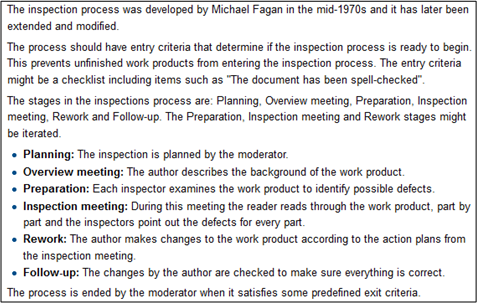

I like capers with my salmon. In general, I also like the work of long time software quality guru Capers Jones. In this Dr. Dobb’s article, “Do You Inspect?”, the caped one extols the virtues of formal inspection. He (rightly) states that formal, Fagan type, inspections can catch defects early in the product development process – before they bury and camouflage themselves deep inside the product until they spring forth way downstream in the customer’s hands. (I hate when that happens!)

The pair of figures below (snipped from the article) graphically show what Capers means. Note that the timeline implies a long, sequential, one-shot, waterfall development process (D’oh!).

That’s all well and dandy, but as usual with mechanistic, waterfall-oriented thinking, the human aspects of doing formal inspections “wrong” aren’t addressed. Because formal inspections are labor-intensive (read as costly), doing artifact and code inspections “wrong” causes internal team strife, late delivery, and unnecessary budget drain. (I hate when that happens!)

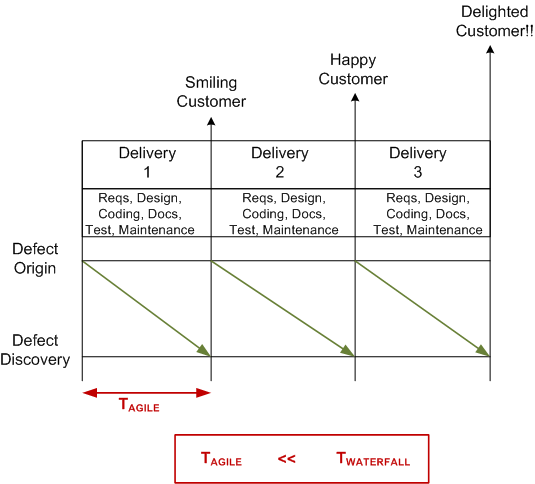

An agile-oriented alternative to boring and morale busting “Fagan-inspections-done-wrong” is shown below. The short, incremental delivery time frames get the product into the hands of internal and external non-developers early and often. As the system grows in functionality and value, users and independent testers can bang on the system, acquire knowledge/experience/insight, and expose bugs before they intertwine themselves deep into the organs of the product. Working hands-on with a product is more exhilarating and motivating than paging through documents and power points in zombie or contentious meetings, no?

Of course, it doesn’t have to be all or nothing. A hybrid approach can be embraced: “targeted, lightweight inspections plus incremental deliveries with hands-on usage”.