Archive

Get Your Beer Here!

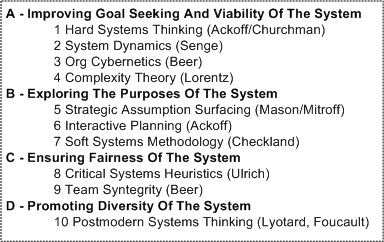

The table below shows a mapping of 10 systems thinking approaches into 4 types based on primary “purpose“. I extracted this table from Michael C. Jackson‘s terrific “Systems Thinking: Creative Holism For Managers“.

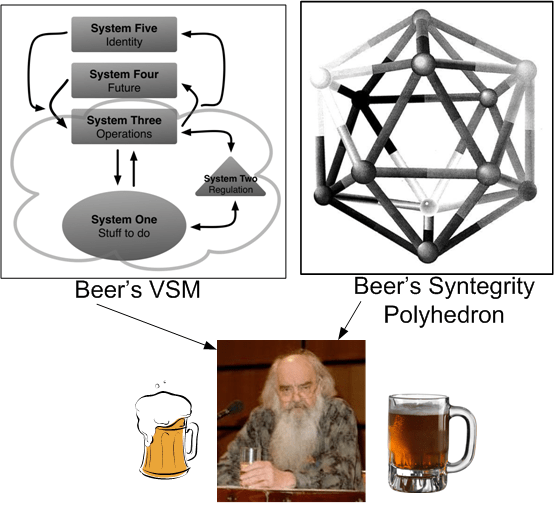

Did you notice that the brilliant Stafford, awesome-last-name, Beer is listed twice and his “Team Syntegrity” approach falls under the “ensuring fairness of the system category“? In Jackson’s opinion, Beer created his cybernetics-based, recursive 5 subsystem, Viable System Model (VSM) for the purpose of improving the goal seeking performance of complex social systems. Beer, both a tasty drink and a staunch anti-hierarchy champion, got so pissed when BMs, BOOGLs, BUTTs, SCOLs and dudes with BFTs interpreted his VSM as just another way of implementing a CCH with omnipotent and omniscient bosses at levels 2-5, that he developed his wildly innovative, polyhedron-based, “Team Syntegrity” approach to ensure fairness in org governance. In his design of the VSM, even though Beer articulated that the sole purpose of subsystems 2-5 is to support the operations of system 1 at the bottom (you know, the DICforce where you and I dwell), people of importance still kept their self-serving UCB blinders on and interpreted his system of management to be hierarchical.

As the figure below shows, the VSM appears to be hierarchical on the surface and, since most (not all) managers operate on the “surface” because they no longer roll up their sleeves to dive into anything difficult to understand, they internalize it as a better way to run their CCH psychic prisons as instruments of domination. However, when one studies Beer’s VSM approach to org management, it’s a self sufficient system of collaboration and intergroup support with each subsystem playing a key role in the holarchy.

In The “Old Days”

In the “old days”, when companies fell upon hard times and had to let some DICs go, or when the DICforce went on strike, jobs were mechanized enough so that managers could fill the holes and keep the joint running until the situation improved. Of course, in most orgs, that is no longer true today since most managers, certainly those that are BMs, shed and conveniently forget their lowly “worker’s skills” as soon as they are promoted out of the cellar into the clique of elites. Thus, a company that cuts front line DICs without cutting some managers puts itself into a deeper grave. Not only does productivity go down because the holes of work expertise go unfilled, but the overhead cost rises because the same number of managers are left to “supervise” fewer DICs. On the other hand, if all or most of the jettisoned DICs were dead weight, the previous sentence may not be true – unless dead weight BMs were retained. But hey, in the minds of most managers (and all of those who fall into the BM category), fellow comrade managers are not dead weight.

Update: Shortly after I queued this post up for publication, a friend(?) serendipitously sent me this link: Lockheed Martin press release. Notice the “delay” that took place from the time they shed 10000 DICs to the time they offered some 600 BOOGLs, CGHs, and SCOLs their (no doubt generous) “Voluntary Executive Separation Program“. Better late than never, right?

Update: Shortly after I queued this post up for publication, a friend(?) serendipitously sent me this link: Lockheed Martin press release. Notice the “delay” that took place from the time they shed 10000 DICs to the time they offered some 600 BOOGLs, CGHs, and SCOLs their (no doubt generous) “Voluntary Executive Separation Program“. Better late than never, right?

The executive reductions will help align the number of senior leaders with the overall decline of about 10,000 in the employee population since the beginning of last year, cut overhead costs and management layers, and increase the Corporation’s speed and agility in meeting commitments.

Nice corpo jargon, no?

Two Paths

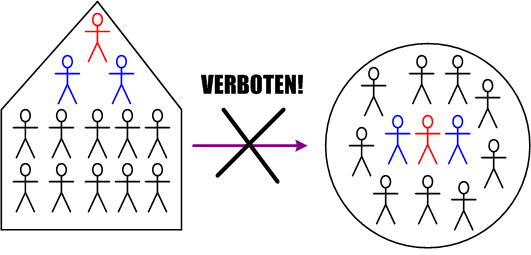

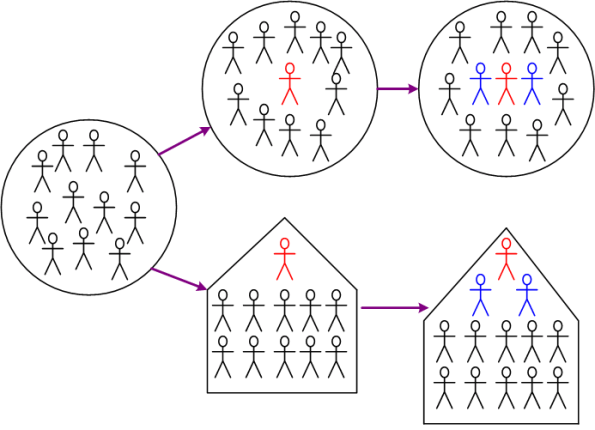

As a small group of people assembled for a purpose greater than each individual grows, some form of structure is required to prevent chaos from reigning. The top path shows the emergence of a group of integral coordinators while the bottom path shows a traditional, stratified CCH being born.

Which group would you rather be a part of? If you say you’d rather be a part of the “circular” group and you’re lucky enough to be a part of one, you’re still likely to get hosed down the road. You see, if your group continues to grow, it will naturally gravitate toward the pyramidal CCH caste system. That is, unless your natural or democratically chosen group leaders don’t morph into CGHs or BOOGLs and they actively prevent the subtle transformation from taking place.

Which group would you rather be a part of? If you say you’d rather be a part of the “circular” group and you’re lucky enough to be a part of one, you’re still likely to get hosed down the road. You see, if your group continues to grow, it will naturally gravitate toward the pyramidal CCH caste system. That is, unless your natural or democratically chosen group leaders don’t morph into CGHs or BOOGLs and they actively prevent the subtle transformation from taking place.

If you’re currently embedded in a CCH and one of its leaders bravely attempts to change the structure to a circular, participative meritocracy, fugg-ed-aboud-it. The change agent will get crushed by his/her clanthinking BOOGL and SCOL peers, who ironically espouse that they want circular behavior while still preserving the stratified CCH.

If you’re currently embedded in a CCH and one of its leaders bravely attempts to change the structure to a circular, participative meritocracy, fugg-ed-aboud-it. The change agent will get crushed by his/her clanthinking BOOGL and SCOL peers, who ironically espouse that they want circular behavior while still preserving the stratified CCH.

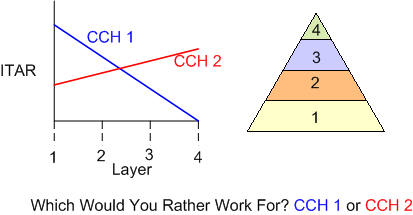

What’s Your ITAR?

A recent personal discovery that revealed itself to me is that “inquiring more and asserting less” is more effective than vice versa. Nonetheless, even after discovering this insight, I’m having a hard time increasing my Inquiry To Assertion Ratio (ITAR).

As you probably know, it’s difficult to change ingrained, long term behavior. When a social situation pops up in which the choice to inquire or assert appears, there often is no choice for me. In order to appear “in the know“, I automatically pull the trigger and make an assertion without asking any questions beforehand. However, I think I’ve made some progress. I can now often detect what I did after the fact. To improve even further, I’m hoping to reach the point where I can detect my transgression instantaneously, in the moment, so that I actually can choose to inquire or assert before I act. Ahhh, that would be nirvana, no?

In patriarchical CCH orgs, the ingrained mindset is such that the higher one moves up in the hierarchy, the lower the ITAR. That’s because BOOGLs and SCOLs unconsciously feel the need to appear infallible in front of the DICforce. Adding fuel to the fire, the DICsters fuel this behavior by expecting patriarchs to be infallible and have all the answers. It’s a self-reinforcing loop of ineffective behavior.

What’s your ITAR? As you age, do you find it rising – or sinking?

What’s your ITAR? As you age, do you find it rising – or sinking?

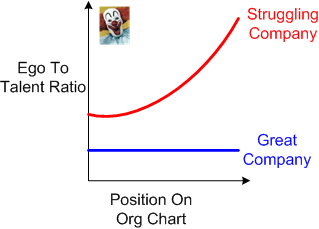

Ego To Talent Ratio

In Scott Berkun‘s “Managing Breakthrough Projects” video, Scott concocts a metric called the Ego-To-Talent ratio (ETTR). Here’s my highly unscientific and speculative curve that plots ETTR versus position on the company org chart.

See that bozo on the chart? That’s me. Where are you?

Crisis?, What Crisis?

The other day, I heard a song on Pandora from one of my fave albums of the 70s (yes, they were called albums back then); Supertramp‘s “Crisis?, What Crisis“. The album title reminded me of orgs that emotionally panic “under the covers” when a crisis occurs, but outwardly behave as if there is no crisis. By “behaving like no crisis is occurring“, I mean that the SCOLs in charge apply whatever band aids they can in the short term to get through the crisis but don’t do anything of substance to stave off, or better handle, future crises.

When the crisis at hand passes, the heroes are congratulated and: the org structure stays the same, the people in the top roles stay the same, the operational business processes remain the same, and most ominously, the patriarchal CCH mindsets stay the same. It’s back to the same-old, same-old, business as usual.

The figure below shows what maybe should happen when crises occur and learning takes place? Someone or some group willingly steps up to positively change the structures and behaviors so that the org can smoothly navigate through, and even thrive within, future crises. In the example below, it took 2 crises to stave off self destruction, right the course, and excel in the future. Alas, the problem with the previous sentence is the “someone or some group” phrase at the beginning.

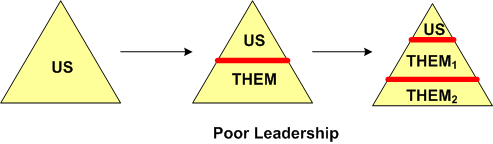

Us And Them

Poor org leaders, or SCOLs, either maintain a stratified “Us And Them” (UAT) line in their orgs or worse – they purposefully create one. By hiring clones of themselves, multiple UAT lines of demarcation appear; choking off open, honest, inter-layer communication and breeding mistrust and disrespect.

Great leaders, or PHORs, skillfully obliterate UAT lines where they exist, or they heroically prevent UAT lines from arising in the first place. Of course, that’s what makes them great leaders.

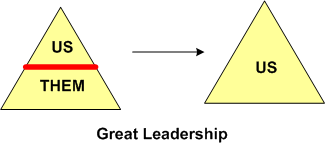

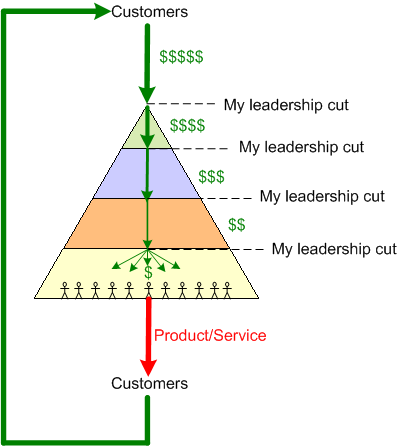

My Leadership Cut

This is the way it is……

Is it the way it should be? Are there any alternatives that could “work”? Are there even any slight variations on this same-old, same-old, scheme that can make it work better compared to the rest of the herd? Nah. No way, right?

Is it the way it should be? Are there any alternatives that could “work”? Are there even any slight variations on this same-old, same-old, scheme that can make it work better compared to the rest of the herd? Nah. No way, right?

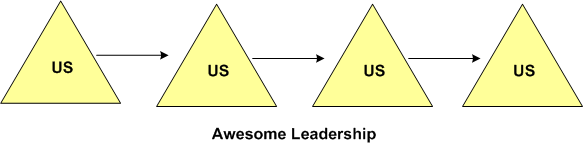

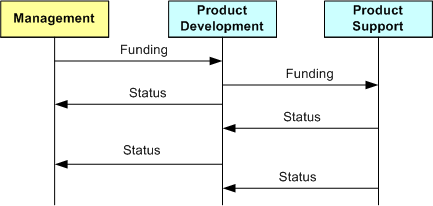

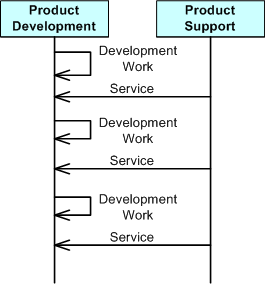

A Change In Funding Source

The figure below shows a dorkily simplistic UML sequence diagram example of the provision of service from a support group (e.g. purchasing, quality assurance, configuration management) to a product development group within a CCH patriarchy. During product development, the team aperiodically requires and requests help from one or more corpo groups who’s raison d’etre is to provide timely support to those who need it.  Depending on who’s leading the support group, the service it provides can be highly responsive and of high quality. However, since the standard “system” setup in all CCH corpocracies is as shown in the sequence diagram below, the likelihood of that being true is low. That’s because in centralized patriarchies, all budgets, salaries, and token rewards are doled out by the sugar daddys perched at the top of the pyramid. On the way down, the middlemen in the path take a cut out of the booty for, uh, the added-value “leadership” they provide to those on the next lower rung in the ladder.

Depending on who’s leading the support group, the service it provides can be highly responsive and of high quality. However, since the standard “system” setup in all CCH corpocracies is as shown in the sequence diagram below, the likelihood of that being true is low. That’s because in centralized patriarchies, all budgets, salaries, and token rewards are doled out by the sugar daddys perched at the top of the pyramid. On the way down, the middlemen in the path take a cut out of the booty for, uh, the added-value “leadership” they provide to those on the next lower rung in the ladder.

In exchange for their yearly/quarterly investments in the lower layers of the caste system, the dudes in the penthouse require periodic status reports (which they can’t understand and which are usually cleverly disguised camouflage) that show progress toward wealth creation from the DICs below.

Since their bread is buttered from the top and not their direct customers, the natural tendency of support groups is to blow off their customers’ needs and concentrate on maximizing their compensation from the top. They do this, either consciously or unconsciously, by adding complexity to the system in the form of Byzantinian procedural labyrinths for customers to follow to show how indispensable they are to the b’ness. As a result, their responsiveness decreases and their customers experience an increase in frustration from shoddily late service.

So how does one fix the standard, dysfunctional, centralized, CCH setup? Check out and ponder the sequence diagram below for a possible attempt at undoing the dysfunctional mess. Can it work? Why, or why not?

By definition, if everyone is doing industry best practice, it’s not best practice. It’s average practice.

Exaggerated And Distorted

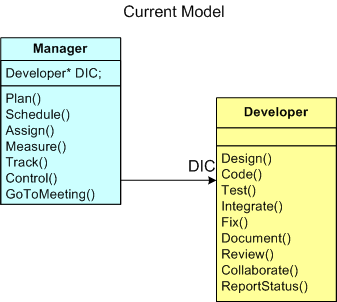

The figure below provides a UML class diagram (“class” is such an appropriate word for this blarticle) model of the Manager-Developer relationship in most software development orgs around the globe. The model is so ubiquitous that you can replace the “Developer” class with a more generic “Knowledge Worker” class. Only the Code(), Test(), and Integrate() behaviors in the “Developer” class need to be modified for increased global applicability.

Everyone knows that this current model of developing software leads to schedule and cost overruns. The bigger the project, the bigger the overruns. D’oh!

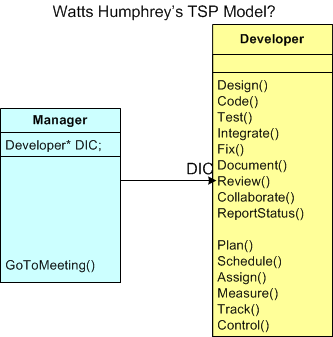

In this article and this interview, Watts Humphrey trumps up his Team Software Process (TSP) as the cure for the disease. The figure below depicts an exaggerated and distorted model of the manger-developer relationship in Watts’s TSP. Of course, it’s an exaggerated and distorted view because it sprang forth from my twisted and tortured mind. Watts says, and I wholeheartedly agree (I really do!), that the only way to fix the dysfunction bred by the current way of doing things is to push the management activities out of the Manager class and down into the Developer class (can you say “empowerment”, sic?). But wait. What’s wrong with this picture? Is it so distorted and exaggerated that there’s not one grain of truth in it? Decide for yourself.

Even if my model is “corrected” by Watts himself so that the Manager class actually adds value to the revolutionary TSP-based system, do you think it’s pragmatically workable in any org structured as a CCH? Besides reallocating the control tasks from Manager to Developer, is there anything that needs to socially change for the new system to have a chance of decreasing schedule and cost overruns (hint: reallocation of stature and respect)? What about the reward and compensation system? Does that need to change (hint: increased workload/responsibility on one side and decreased workload/responsibility on the other)? How many orgs do you know of that aren’t structured as a crystalized CCH?

Strangely (or not?), Watts doesn’t seem to address these social system implications of his TSP. Maybe he does, but I just haven’t seen his explanations.