Archive

Pick And Own

No, the title of this blost (short for blog-post and pronounced “blow-ssst”) is not “pick your nose“. It’s “pick and own“. My friend Bill Livingston uses the following catchy and true phrase throughout his book “Design For Prevention“:

He who picks the parts owns the behavior. – Unknown

This is certainly true in the world of software development for new projects. For maintenance projects, which comprise the vast majority of software work, this dictum also holds:

He who touched the code last owns the stank. – Unknown

Bill also truly but sadly states that when something goes awry, the dude who “picks the parts” or “owns the stank” is immediately sought out for punishment. When everything goes smoothly, the identity of the designer/maintainer magically disappears.

Punishment but no praise. Such is the life of a DIC. BMs, CGHs and CCRATS on the other hand, clever as they are, flip everything upside down. Since they don’t pick or maintain anything, they never get blamed for anything that goes wrong. Going one step further, they constantly praise themselves and their brethren while giddily playing the role of DIC-punisher and blamer.

WTF you say? If you fellow DICsters didn’t know this already, then accept it and get used to it because it’ll sting less when it happens over and over again. Tis the way the ancient system of patriarchical CCH institutions is structured to work. It doesn’t matter who the particular cast of characters in the upper echelons are. They could individually be great guys/gals, but their collective behavior is ubiquitously the same.

The Best Defense

In “The Design Of Design“, Fred Brooks states:

The best defense against requirements creep is schedule urgency.

Unfortunately, “schedule urgency” is also the best defense against building a high quality and enduring system. Corners get cut, algorithm vetting is skipped, in-situ documentation is eschewed, alternative designs aren’t investigated, and mistakes get conveniently overlooked.

Yes, “schedule urgency” is indeed a powerful weapon. Wield it carefully, lest you impale yourself.

Unconstrained To Constrain

As I continue to slowly inhale Fred Brooks‘s book, “The Design Of Design“, I’m giddily uncovering all kinds of diamonds in the rough. Fred states:

“If designers use a structured annotation or software tool during design it will restrict the ease of having vague ideas, impeding conceptual design.”

Ain’t that the truth? Don’t those handcuffing “standard document templates, processes, procedures, work instructions” that you’re required to follow to ensure quality (lol!) frustratingly constrain you from doing your best work?

Along the same lines, Fred hits another home run in my ballpark (which is devoid of adoring and paying fans, of course):

“I believe that a generic diagramming tool, with features such as automatic layout of trees, automatic rerouting of relationship arrows, and searchable nodes, is better suited to (design) tree capture. Microsoft Visio or SmartDraw might be such a choice.”

Man, this one almost made me faint and lose consciousness. I live, eat, and breath “Visio”. Every picture that you’ve seen in this blog and every design effort that I undertake at work starts with, and ends with, Visio – which is the greatest tool of expression I’ve ever used. I’ve tried “handcuffers” like Artisan Studio and Enterprise Architect as software design aids, but they were too frustratingly complex and constraining to allow me to conjure up self-satisfying designs.

All designs must eventually be constrained so that they can be built and exploited for profit. But in order to constrain, one must be unconstrained. How’s that for a zen-like paradox?

Conceptual Integrity

Like in his previous work, “The Mythical Man Month“, in “The Design Of Design“, Fred Brooks remains steadfast to the assertion that creating and maintaining “conceptual integrity” is the key to successful and enduring designs. Being a long time believer in this tenet, I’ve always been baffled by the success of Linux under the free-for-all open source model of software development. With thousands of people making changes and additions, even under Linus Torvalds benevolent dictatorship, how in the world could the product’s conceptual integrity defy the second law of thermodynamics under the onslaught of such a chaotic development process?

Fred comes through with the answers:

- A unifying functional specification is in place: UNIX.

- An overall design structure, initially created by Torvalds, exists.

- The builders are also the users – there are no middlemen to screw up requirements interpretation between the users and builders.

If you extend the reasoning of number 3, it aligns with why most of the open source successes are tools used by software developers and not applications used by the average person. Some applications have achieved moderate success, but not on the scale of Linux and other application development tools.

Skill Acquisition

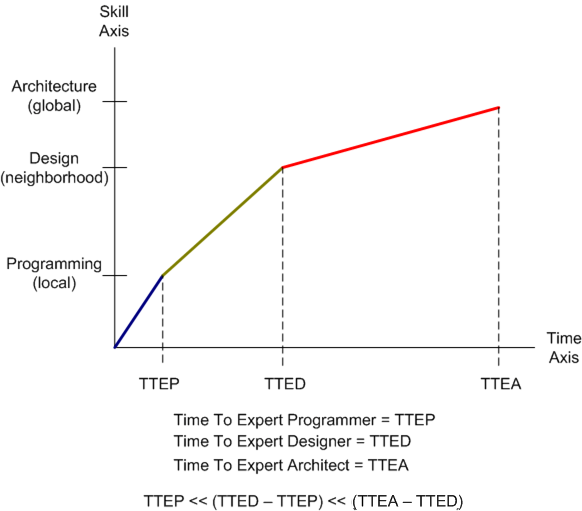

Check out the graph below. It is a totally made up (cuz I like to make things up) fabrication of the relationship between software skill acquisition and time (tic-toc, tic-toc). The y-axis “models” a simplistic three skill breakdown of technical software skills: programming (in-the-very-small) , design (in-the-small) and architecture (in-the-large). The x-axis depicts time and the slopes of the line segments are intended to convey the qualitative level of difficulty in transitioning from one area of expertise into the next higher one in the perceived value-added chain. Notice that the slopes decrease with each transition; which indicates that it’s tougher to achieve the next level of expertise than it was to achieve the previous level of expertise.

The reason I assert that moving from level N to level N+1 takes longer than moving from N-1 to N is because of the difficulty human beings have dealing with abstraction. The more concrete an idea, action or thought is, the easier it is to learn and apply. It’s as simple as that.

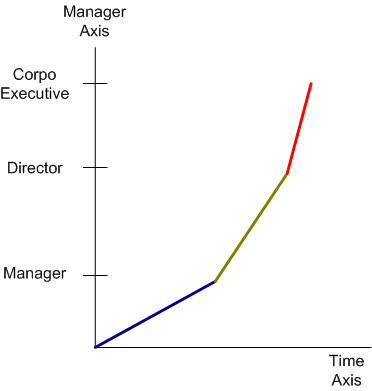

The figure below shows another made up management skill acquisition graph. Note that unlike the technical skill acquisition graph, the slopes decrease with each transition. This trend indicates that it’s easier to achieve the next level of expertise than it was to achieve the previous level of expertise. Note that even though the N+1 level skills are allegedly easier to acquire over time than the Nth level skill set, securing the next level title is not. That’s because fewer openings become available as the management ladder is ascended through whatever means available; true merit or impeccable image.

Error Acknowledgement: I forgot to add a notch with the label DIC at the lower left corner of the graph where T=0.

CCP

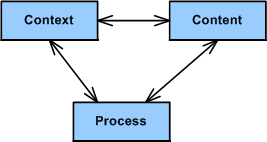

Relax right wing meanies, it’s not CCCP. It’s CCP, and it stands for Context, Content, and Process. Context is a clear but not necessarily immutable definition of what’s in and what’s out of the problem space. Content is the intentionally designed static structure and dynamic behavior of the socio-technical solution(s) to be applied in an attempt to solve the problem. Process is the set of development activities, tasks, and toolboxes that will be used to pre-test (simulate or emulate), construct, integrate, post-test, and carefully introduce the solution into the problem space. Like the other well-known trio, schedule-cost-quality, the three CCP elements are intimately coupled and inseparable. Myopically focusing on the optimization of one element and refusing to pay homage to the others degrades the performance of the whole.

I first discovered the holy trinity of CCP many years ago by probing, sensing, and interpreting the systems work of John Warfield via my friend, William Livingston. I’ve been applying the CCP strategy for years to technical problems that I’ve been tasked to solve.

You can start using the CCP problem solving process by diving into any of the three pillars of guidance. It’s not a neat, sequential, step-by-step process like those documented in your corpo standards database (that nobody follows but lots of experts are constantly wasting money/time to “improve”). It’s a messy, iterative, jagged, mistake discovering and correcting intellectual endeavor.

I usually start using CCP by spending a fair amount of time struggling to define the context; bounding, iterating and sketching fuzzy lines around what I think is in and what is out of scope. Next, I dive into the content sub-process; using the context info to conjure up solution candidates and simulate them in my head at the speed of thought. The first details of the process that should be employed to bring the solution out of my head and into the material world usually trickle out naturally from the info generated during the content definition sub-process. Herky-jerky, iterative jumping between CCH sub-processes, mental simulation, looping, recursion, and sketching are key activities that I perform during the execution of CCP.

What’s your take on CCP? Do you think it’s generic enough to cover a large swath of socio-technical problem categories/classes? What general problem solving process(es) do you use?

The Factory And The Widgets

The process to assemble and construct the factory is much more challenging than the process to assemble and construct the widgets that the factory repetitively stamps out. In the software industry, everything’s a factory, but most managers think everything’s a widget in order to delude themselves into thinking that they’re in control. Amazingly, this is true even if the manager used to write software him/herself.

When a developer gets “promoted” to manager, a switch flips and he/she forgets the factory versus widget dichotomy. This stunning and instantaneous about face occurs because pressure from the next higher layer in the dysfunctional CCH (Command and Control Hierarchy) causes the shift in mindset and all common sense goes out the window. Predictability and exploitation replace uncertainty and exploration in all situations that demand the latter; and software creation always demands the latter. Conversation topics flip from talking about technical and CCH org roadblocks to obsessing about schedule and budget conservation because, of course, managers equate writing software with secretarial typing. The problem is that neglecting the former leads to poor performance of the latter.

Structure And The “ilities”

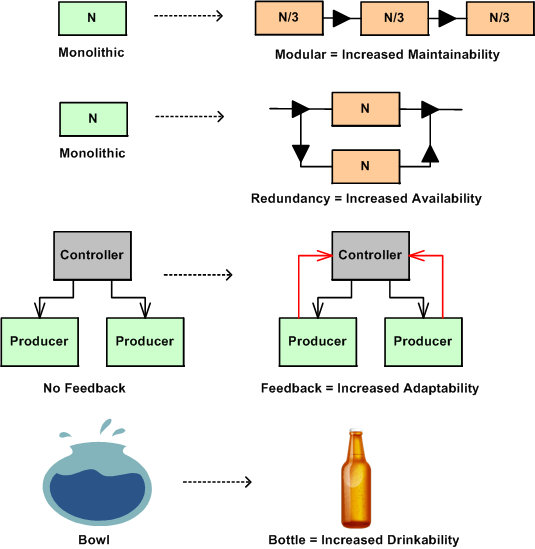

In nature, structure is an enabler or disabler of functional behavior. No hands – no grasping, no legs – no walking, no lungs – no living. Adding new functional components to a system enables new behavior and subtracting components disables behavior. Changing the arrangement of an existing system’s components and how they interconnect can also trade-off qualities of behavior, affectionately called the “ilities“. Thus, changes in structure effect changes in behavior.

The figure below shows a few examples of a change to an “ility” due to a change in structure. Given the structure on the left, the refactored structure on the right leads to an increase in the “ility” listed under the new structure. However, in moving from left to right, a trade-off has been made for the gain in the desired “ility”. For the monolithic->modular case, a decrease in end-to-end response-ability due to added box-to-box delay has been traded off. For the monolithic->redundant case, a decrease in buyability due to the added purchase cost of the duplicate component has been introduced. For the no feedback->feedback case, an increase in complexity has been effected due to the added interfaces. For the bowl->bottle example, a decrease in fill-ability has occurred because of the decreased diameter of the fill interface port.

The plea of this story is: “to increase your aware-ability of the law of unintended consequences”. What you don’t know CAN hurt you. When you are bound and determined to institute what you think is a “can’t lose” change to a system that you own and/or control, make an effort to discover and uncover the ilities that will be sacrificed for those that you are attempting to instill in the system. This is especially true for socio-technical systems (do you know of any system that isn’t a socio-technical system?) where the influence on system behavior by the technical components is always dwarfed by the influence of the components that are comprised of groups of diverse individuals.

Architectural, Mechanistic, And Detailed

Bruce Powel Douglass is one of my favorite embedded systems development mentors. One of his ideas is to categorize the activity of design into three levels of increasingly detailed abstraction:

- Architectural (5 views)

- Mechanistic

- Detailed

The SysML figure below tries to depict the conceptual differences between these levels. (Even if you don’t know the SysML, can you at least viscerally understand the essence of what the drawings are attempting to communicate?)

Since the size, algorithmic density, and safety critical nature of the software intensive systems that I’ve helped to develop require what the agile community mocks as BDUF (Big Design Up Front), I’ve always communicated my “BDUF” designs in terms of the first and third abstractions. Thus, the mechanistic design category is sort of new to me. I like this category because it shortens the gulf of understanding between the architectural and the detailed design levels of abstraction. According to Mr. Douglass, “mechanistic design” is the act of optimizing a system at the level of an individual collaboration ( a set of UML classes or SysML blocks working closely together to realize a single use case). From now on, I’m gonna follow his three tier taxonomy in communicating future designs, but only when it’s warranted, of course (I’m not a religious zealot for or against any method), .

BTW, if you don’t do BDUF, you might get CUDO (Crappy and Unmaintanable Design Out back). Notice that I said “might” and not “will”.

Distributed Vs. Centralized Control

The figure below models two different configurations of a globally controlled, purposeful system of components. In the top half of the figure, the system controller keeps the producers aligned with the goal of producing high quality value stream outputs by periodically sampling status and issuing individualized, producer-specific, commands. This type of system configuration may work fine as long as:

- the producer status reports are truthful

- the controller understands what the status reports mean so that effective command guidance can be issued when problems manifest.

If the producer status reports aren’t truthful (politics, culture of fear, etc.), then the command guidance issued by the controller will not be effective. If the controller is clueless, then it doesn’t matter if the status reports are truthful. The system will become “hosed”, because the inevitable production problems that arise over time won’t get solved. As you might guess, when the status reports aren’t truthful and the controller is clueless, all is lost. Bummer.

The system configuration in the bottom half of the figure is designed to implement the “trust but verify” policy. In this design, the global controller directly receives samples of the value streams in addition to the producer status reports. The integration of value stream samples to the information cache available to the controller takes care of the “untruthful status report” risk. Again, if the controller is clueless, the system will get hosed. In fact, there is no system configuration that will work when the controller is incompetent.

How many system controllers do you know that actually sample and evaluate value stream outputs? For those that don’t, why do you think they don’t?

The system design below says “syonara dude” to the global omnipotent and omniscient controller. Each producer cell has its own local, closely coupled, and knowledgeable controller. Each local controller has a much smaller scope and workload than the previous two monolithic global controller designs. In addition, a single clueless local controller may be compensated for if the collective controller group has put into place a well defined, fair, and transparent set of criteria for replacement.

What types of systems does your organization have in place? Centrally controlled types, distributed control types, a mixture of both, hybrids? Which ones work well? How do you see yourself in your org? Are you a producer, a local controller, both a local controller and a producer, an overconfident global controller, a narcissistic controller of global controllers, a supreme controller of controllers who control other controllers who control yet other controllers? Do you sample and evaluate the value stream?