Archive

Dude, Read It The Freakin’ First Time

Recently, I was asked by Joe Manager to estimate the amount of resources (people and time) that I thought would be consumed in the development of a large, computationally-intensive, software-centric system. I dutifully did what was asked of me and posted a coarse, first cut estimate on the company wiki for all to scrutinize. I also provided a link to the page to Joe Manager. Unsurprisingly (to me at least) , at the next “planning” meeting I was asked again by Joe, on-the-spot and in real-time, what it would take to do the job if I were to lead the project. Since my pre-meeting intuition told me to bring a hard copy of my estimate to the meeting, I presented it to Mr. Manager and gently reminded him that I had forwarded it to him earlier when he asked for it the (freakin’) first time.

Apparently, besides being forgetful, poor Joe wasn’t told of the not-so-secret policy that I’m not allowed to lead anyone, let alone a team on a large and costly software development project that could be pretty important to the company’s future. Plus, since Joe’s last name is “Manager”, isn’t he supposed to at least consider planning and leading the effort his own freakin’ self? Or is he just envisioning someone else struggling to get it done while he periodically samples status, rides the schedule, and watches from the grassy knoll.

In a bacon and eggs breakfast, the chicken is involved, but the pig is committed – Ken Schwaber

Ya Can’t Put The Cat Back In The Bag

Check out this snippet from “Can Larger Companies Still be Passionate and Quirky?“:

Writing for The New York Times, Adam Bryant conducted an interview with Tony Hsieh, the chief executive of Zappos.com. Part of the interview that intrigued me was Hsieh’s explanation of why he and his roommate sold their company LinkExchange to Microsoft in 1998.

Part of it was the money, he admits. But, mostly, it was because the passion and excitement that permeated the company in the beginning was gone, and he’d grown to dislike its culture:

“When it was starting out, when it was just 5 or 10 of us, it was like your typical dot-com. We were all really excited, working around the clock, sleeping under our desks, had no idea what day of the week it was. But we didn’t know any better and didn’t pay attention to company culture. By the time we got to 100 people, even though we hired people with the right skill sets and experiences, I just dreaded getting out of bed in the morning and was hitting that snooze button over and over again.”

To avoid this happening with Zappos, Hsieh says he formalized the definition of the Zappos culture into 10 core values; core values that they would be willing to hire and fire people based on. Read the interview with Hsieh for details on how they went about this.

With LinkExchange, Tony was wise enough to know that it was fruitless to try and restore the company’s original esprit de corps culture. Once the cat gets out of the bag, it’s pretty much a done deal that you won’t get it back in.

What’s mind boggling to me is that leaders of startups that grow and “mature” over time don’t even have a clue that the vibrant culture of community/comraderie that they originally created has petered out. They get disconnected and buffered from the day to day culture by adding layer upon layer of pyramidal stratification and they delude themselves into thinking the culture has been maintained “for free” over the duration. Those dudes deserve what they get; a transformation from a communal meritocracy into a corpo mediocracy just like the rest of the moo-herd.

Dependable Mission Critical Software

In this post, Embedded.com – Software for dependable systems, Jack Gannsle introduced me to the book: Software for Dependable Systems–Sufficient Evidence?. It was written by the “Committee on Certifiably Dependable Software Systems” and it’s available for free pdf download.

Despite being written by a committee (blech!), and despite the bland title (yawn), I agree with Jack in that it’s a riveting geek read. It’s understandable to field-hardened practitioners and it’s filled with streetwise wisdom about building dependability into large, mission critical software systems that can kill people or cause massive financial loss if they collapse under stress. Essentially, it says that all the bloated, costly, high-falutin safety and security and certification processes in existence today don’t guarantee squat – except jobs for self-important bureaucrats and wanna-be-engineers. They don’t say it THAT way of course, but that’s my warped and unprofessional interpretation of their message.

Here are a few gems from the 149 page pdf:

As is well known to software engineers, by far the largest class of problems arises from errors made in eliciting, recording, and analysis of requirements.

Undependable software suffers from an absence of a coherent and well articulated conceptual model.

Today’s certification regimes and consensus standards have a mixed record. Some are largely ineffective, and some are counterproductive. (<- This one is mind blowing to me)

The goal of certifiably dependable software cannot be achieved by mandating particular processes and approaches regardless of their effectiveness in certain situations.

In addition to lampooning the “way things are currently done” for certifying software-centric dependability, the committee dudes actually make some recommendations for improving the so-called state of art. Stunningly, they don’t prescribe yet another costly, heavyweight process of dubious effectiveness. They recommend any process comprised of best practices; as long as there is scrutable connectivity from phase to phase and from start to end to “preserve the chain of evidence” for a claim of dependability that vendors of such software should be required to make. Where there is a gap between links in the chain of scrutability, they recommend rigorous analysis to fill it.

To make the transition to the new mindset of scrutable connectivity, they say that these skills, which are rare today and difficult to acquire, will be required in the future:

- True systems thinking (not just specialized, localized, algorithmic thinking that’s erroneously praised as systems thinking by corpocracies) of the properties of the system as a whole and the interactions among its components.

- The art of simplifying complex concepts, which is difficult to appreciate since the awareness of the need for simplification usually only comes (if it DOES come at all) with bitter experience and the humility gained from years of practice.

Drum roll please, because my absolute favorite entry in the book, which tugs at my heart, is as follows:

To achieve high levels of dependability in the foreseeable future, striving for simplicity is likely to be by far the most cost-effective of all interventions. Simplicity is not easy or cheap but its rewards far outweigh its costs.

That passage resonates deeply with me because, even though I’m not good at it, that’s what my primary professional goal has been for 20+ years. Clueless companies that put complexifying and obfuscating experts that nobody can understand up on a pedestal, deserve what they get:

- incomprehensible, unmaintainable, and undependable products

- a disconnected and apathetic workforce

- low (if any) profit margins.

As my Irish friend would say, they are all fecked up. They’re innocent and ignorant, but still fecked up.

Byzantine Labyrinth

During the birth and growth of dysfunctional CCHs, here is what happens:

- silos form and harden,

- a bewildering array of narrow specialist roles get continuously defined,

- layers of self-important and entitled RAPPERS emerge, and

- a byzantine labyrinth of processes and procedures are created by those in charge.

This not only happens under the “watchful eyes” of the head shed, but incredibly, those inside the shed-of-privilege are the chief proponents and instigators of all the added crap that slows down and frustrates the DICforce. Peter Drucker nailed it when he opined:

Ninety percent of what we call ‘management’ consists of making it difficult for people to get things done – Peter Drucker

On the other hand, T.S. Eliot also pegged it with:

“Half of the harm that is done in this world is due to people who want to feel important. They do not mean to do harm… They are absorbed in the endless struggle to think well of themselves.” – T. S. Eliot

Context Switching

“There is time enough for everything in the course of the day, if you do but one thing at once, but there is not time enough in the year, if you will do two things at a time.” – Lord Chesterfield (1740)

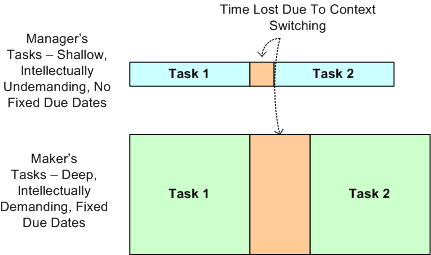

Study after study after study have shown that, due to the natural imperfections built into human memory, multitasking is inefficient and unproductive compared to single-tasking. The bottom line is that humans suck at multitasking. Unlike computers, when humans switch from doing one thought-intensive task to another, the clearing out of memory content from the current task and the restoration of memory content from the previous task greatly increases the chances of errors and mistakes being made.

So why do managers multitask all the time, and why do unenlightened companies put “multitasking prowess” on their performance review forms? Ironically, they do it to reinforce an illusion that multitasking is a key contributor of great productivity and accomplishment. When a “performance reviewer” sees the impressive list of superficial accomplishments that a multitasker has achieved and compares it to a measly list of one or two deep accomplishments from a single-tasker, an illusion of great productivity is cemented in the mind of the ignorant reviewer. Most managers, huge multitaskers themselves, and clueless to the detrimental effects of the malady on performance, tend to reward fellow multitaskers more than non-multitasking “slackers“. Bummer for all involved; especially the org as a whole.

Unscalable Orgs

My friend Byron Davies sent me a link to this 3 minute MIT Media Lab video in which associate Media Lab Director Andy Lippman challenges us to recognize four common flaws plaguing all of our institutions. Obtaining a new awareness and understanding of the plague is the first step toward meaningful redesign.

According to Lippman, the top four reasons for organizational decline are:

- They’re out of scale – they’ve grown too big to perform in accordance with their original design

- They’re monocultures – they all act the same

- They’re opaque – nobody from within or without understands how they freakin’ work

- They’ve lost their original mission – A summation of the previous three reasons.

Because of the pervasive institutional obsession for growth, Lippman seems to think that solving the scaling problem through the development of nested communities is the most promising strategy for halting the decline.

A Unique Core Value

Unless they’ve been cleverly camouflaging their sinister ways from the world’s prying eyes, the people at Zappos.com truly do live and breathe their corporate values every day. My favorite, and perhaps most unique Zappos core value is number three: “Create Fun and a Little Weirdness“. Here’s how the Zappos team describes this precious gem from the viewpoint of their “Core Values Frog” (CVF):

Our CVF has a sense of humor; he knows that it’s good to laugh at yourself every once in a while. Work shouldn’t be synonymous with drudgery; CVF can find fun and weirdness even when the rubber meets the road and we’re getting lots done. Being a little weird requires being a little innovative, and CVF is always looking for a chance to fully engage in his work and bring out the fun and weird side of it.

In tribute to CV #3, the people at Zappos have held impromptu parades, hula hoop contests, head shavings, and all kinds of other weird events both on and off the company’s premises.

Of course, Zappos is just a lowly $1B retail shoe company and your business is much more different, respectful, and prestigious. Thus, it’s patently obvious that Zappos core value #3 can’t possibly work in your corpo palace. Right?

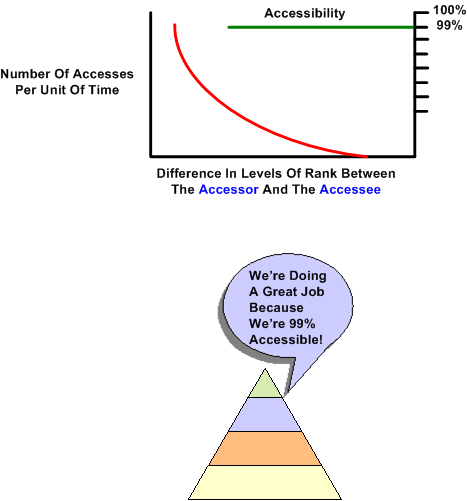

Accessible And Accessed

One of the metrics that a lot of corpo hierarchs assess themselves on is how accessible they are to their people. However, being accessible (textbook open door policy, walking the halls, e-mail, pseudo-mandated all hands meetings) doesn’t mean being accessed. For obvious reasons, they don’t measure themselves on this important metric, especially how frequently they are accessed (voluntarily and unsolicited) by their non-direct reports. In the vast majority of corpocracies, the number of accesses per unit of time goes down as the difference between caste levels of the accessor and accessee goes up. Just because that’s the way it’s always been doesn’t mean that’s the way it should or could be.

We Don’t Want Yours

We want our group to be less conflict averse so that the best ideas can be forged within the crucible of debate and (sometimes) heated dialog. We also want passion from our people. As a matter of fact, we demand it of everyone in our group.

BUT!

We don’t approve of your over-the-top confrontational style and we don’t approve of the ways that you externalize your passion. Sadly, we don’t have any role models in our management ranks to lead the “conflict aversion reduction and passion elevation” initiative. Thus, we have no clue of how we want our people to initiate confrontation or express passion, but we’ll know it when we see it, of course.

WTF?

Open Kimono

I continue to be enamored and awed by the way the leadership at zappos.com operates the company. I’m convinced that they’re the real deal. They’ve obtained a level of business nirvana that balances altruism with profitability which is perhaps unmatched by any other company on earth – except for maybe Semco.

Sadly, even though Zappos continuously and willingly opens its kimono to all those who care to learn about how they nurture and sustain their success, the Zappos operational model probably won’t go very far. The endless sea of power-obsessed dinosaurs that rule the corpo roost are too clever (cleverness is how they got into the protected nest in the first place).

The most common refrain for rejecting any attempt to emulate Zappos “best practices” will be: “none of that stuff will work here because our business is totally different“. These will be the words of wisdom uttered from the same moo-herd potty mouths that repetitively proclaim “customers are number one and our employees are our most valuable asset“. Blah, blah, blah. Yawn, yawn, yawn. BS, BS, BS.