Archive

Context Sensitive Keywords

Update: Thanks to Chris’s insightful comment, the title of this post should have been “Context Sensitive Identifiers“. “override” and “final” are not C++ keywords; they are identifiers with special meaning.

If maintaining backward compatibility is important, then introducing a new keyword into a programming language is always a serious affair. Introducing a new keyword that is already used in millions of lines of existing code as an identifier (class name, namespace name, variable name, etc), can break a lot of product code and discourage people from upgrading their compilers and using the new language/library features.

Unlike other languages, backward compatibility is a “feature” (not a “meh“) in C++. Thus, the proposed introduction of a new keyword is highly scrutinized by the standards committee when core language improvements are considered. This is the main reason why the verbosity-reducing “auto” keyword wasn’t added until the C++11 standard was hatched.

Even though Bjarne Stroustrup designed/implemented “auto” in C++ over 30 years ago to provide for convenient compiler type deduction, the priority for backward compatibility with C caused it to be sh*t-canned for decades. However, since (hopefully) nobody uses it in C code anymore (“auto” is the default storage type for all C local variables – so why be redundant?), the time was deemed right to include it in the C++11 release. Of course, some really, really old C/C++ code will get broken when compiled under a new C++11 compiler, but the breakage won’t be as dire as if “auto” had made it into the earlier C++98 or C++03 standards.

With the seriousness of keyword introduction in mind, one might wonder why the “override” and “final” keywords were added to C++11. Surely, they’re so common that millions of lines of C/C++ legacy code will get broken. D’oh!

But wait! To severely limit code-breakage, the “override” and “final” keywords are defined to be context sensitive. Unless they’re used in a purposefully narrow, position-specific way, C++11 compilers will reject the source code that contains them.

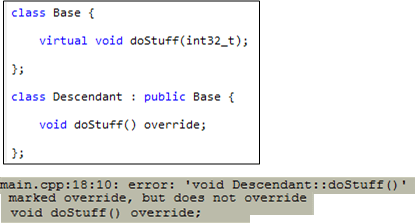

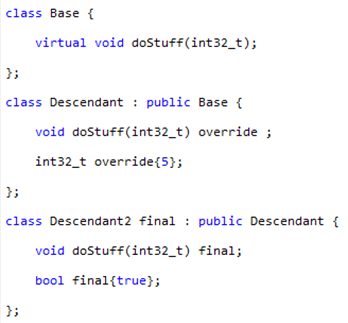

The “final” keyword (used to explicitly prevent further inheritance and/or virtual function overriding) can only be used to qualify a class definition or a virtual function declaration. The closely related “override” keyword (used to prevent careless mistakes when declaring a virtual function) can only be used to qualify a virtual function. The figure below shows how “final” and “override” clarify programmer intention and prevent accidental mistakes.

Because of the context-specific constraints imposed on the “final” and “override” keywords, this (crappy) code compiles fine:

The point of this last code fragment is to show that the introduction of context-specific keywords is highly unlikely to break existing code. And that’s a good thing.

Looks Weird, But Don’t Be Afraid To Do It

Modern C++ (C++11 and onward) eliminates many temporaries outright by supporting move semantics, which allows transferring the innards of one object directly to another object without actually performing a deep copy at all. Even better, move semantics are turned on automatically in common cases like pass-by-value and return-by-value, without the code having to do anything special at all. This gives you the convenience and code clarity of using value types, with the performance of reference types. – C++ FAQ

Before C++11, you’d have to be tripping on acid to allow a C++03 function definition like this to survive a code review:

std::vector<int> moveBigThingsOut() {

const int BIGNUM(1000000);

std::vector<int> vints;

for(int i=0; i<BIGNUM; ++i) {

vints.push_back(i);

}

return vints;

}

Because of: 1) the bolded words in the FAQ at the top of the page, 2) the fact that all C++11 STL containers are move-enabled (each has a move ctor and a move assignment member function implementation), 3) the fact that the compiler knows it is required to destruct the local vints object just before the return statement is executed, don’t be afraid to write code like that in C++11. Actually, please do so. It will stun reviewers who don’t yet know C++11 and may trigger some fun drama while you try to explain how it works. However, unless you move-enable them, don’t you dare write code like that for your own handle classes. Stick with the old C++03 pass by reference idiom:

void passBigThingsOut(std::vector<int>& vints) {

const int BIGNUM(1000000);

vints.clear();

for(int i=0; i<BIGNUM; ++i) {

vints.push_back(i);

}

}

Which C++11 user code below do you think is cleaner?

//This one-liner?

auto vints = moveBigThingsOut();

//Or this two liner?

std::vector<int> vints{};

passBigThingsOut(vints);

Move Me, Please!

UPDATE: Don’t read this post. It’s wrong, sort of 🙂 Actually, please do read it and then go read John’s comment below along with my reply to him. D’oh!

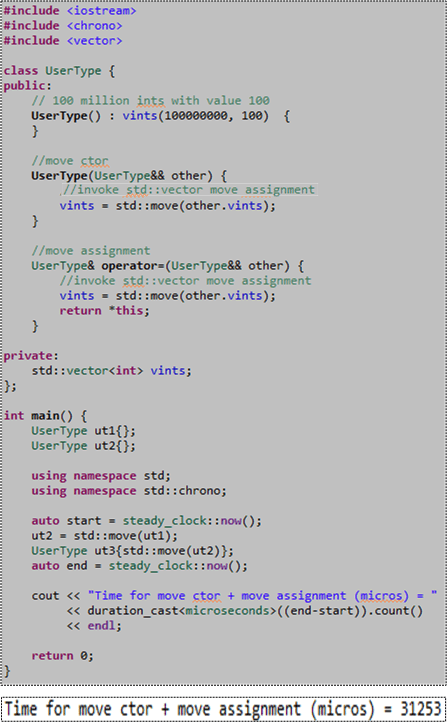

Just because all the STL containers are “move enabled” in C++11, it doesn’t mean you get their increased performance for free when you use them as member variables in your own classes. You don’t. You still have to write your own “move” constructor and “move” assignment functions to obtain the superior performance provided by the STL containers. To illustrate my point, consider the code and associated console output for a typical run of that code below.

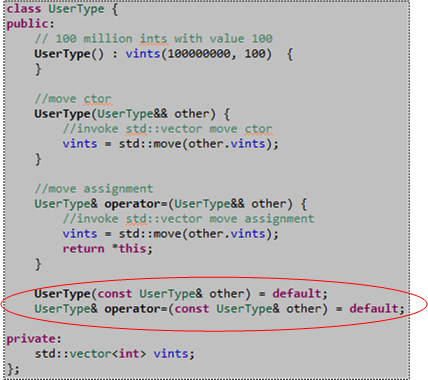

Please note the 3o-ish millisecond performance measurement we’ll address later in this post. Also note that since only the “move” operations are defined for the UserType class, if you attempt to “copy” construct or “copy” assign a UserType object, the compiler will barf on you (because in this case the compiler doesn’t auto-generate those member functions for you):

However, if you simply add “default” declarations of the copy ctor and copy assignment operations to the UserType class definition, the compiler will indeed generate their definitions for you and the above code will compile cleanly:

Ok, now remember that 30-ish millisecond performance metric we measured for “move” performance? Let’s compare that number to the performance of a “copy” construct plus “copy” assign pair of operations by adding this code to our main() function just before the return statement:

After compiling and running the code that now measures both “move” and “copy” performance, here’s the result of a typical run:

As expected, we measured a big boost in performance, 5X in this case, by using “moves” instead of old-school “copies“. Having to wrap our args with std::move() to signal the compiler that we want a “move” instead of “copy” was well worth the effort, no?

Summarizing the gist of this post; please don’t forget to write your own simple “move” operations if you want to leverage the “free” STL container “move” performance gains in the copyable classes you write that contain STL containers. 🙂

NOTE1: I ran the code in this post on my Win 8.1 Lenovo A-730 all-in-one desktop using GCC 4.8/MinGW and MSVC++13. I also ran it on the Coliru online compiler (GCC 4.8). All test runs yielded similar results. W00t!

NOTE2: When I first wrote the “move” member functions for the UserType class, I forgot to wrap other.vints with the overhead-free std::move() function. Thus, I was scratching my (bald) head for a while because I didn’t know why I wasn’t getting any performance boost over the standard copy operations. D’oh!

NOTE3: If you want to copy and paste the code from here into your editor and explore this very moving topic for yourself, here is the non-.png listing:

#include <iostream>

#include <chrono>

#include <vector>

class UserType {

public:

// 100 million ints with value 100

UserType() : vints(100000000, 100) {

}

//move ctor

UserType(UserType&& other) {

//invoke std::vector move assignment

vints = std::move(other.vints);

}

//move assignment

UserType& operator=(UserType&& other) {

//invoke std::vector move assignment

vints = std::move(other.vints);

return *this;

}

UserType(const UserType& other) = default;

UserType& operator=(const UserType& other) = default;

private:

std::vector<int> vints;

};

int main() {

UserType ut1{};

UserType ut2{};

using namespace std;

using namespace std::chrono;

auto start = steady_clock::now();

ut2 = std::move(ut1);

UserType ut3{std::move(ut2)};

auto end = steady_clock::now();

cout << "Time for move ctor + move assignment (micros) = "

<< duration_cast<microseconds>((end-start)).count()

<< endl;

UserType ut4{};

UserType ut5{};

start = steady_clock::now();

ut5 = ut4;

UserType ut6{ut5};

end = steady_clock::now();

cout << "Time for copy ctor + copy assignment (micros) = "

<< duration_cast<microseconds>((end-start)).count()

<< endl;

return 0;

}

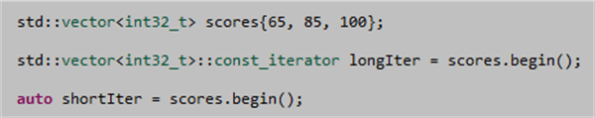

Auto Forgetfulness

The other day, I started tracking down a defect in my C++11 code that was exposed by a unit test. At first, I thought the bugger had to be related to the domain logic I was implementing. However, after 4 hours of inspection/testing/debugging, the answer simply popped into my head, seemingly out of nowhere (funny how that works, no?). It was due to my “forgetting” a subtle characteristic of the C++11 automatic type deduction feature implemented via the “auto” keyword.

To elaborate further, take a look at this simple function prototype:

SomeReallyLongTypeName& getHandle();

On first glance, you might think that the following call to getHandle() would return a reference to an internal, non-temporary, object of type SomeReallyLongTypeName that resides within the scope of the getHandle() function.

auto x = getHandle();

However, it doesn’t. After execution returns to the caller, x contains a copy of the internal, non-temporary object of type SomeReallyLongTypeName. If SomeReallyLongTypeName is non-copyable, then the compiler would have mercifully clued me into the problem with an error message (copy ctor is private (or deleted)).

To get what I really want, this code does the trick:

auto& x = getHandle();

The funny thing is that I already know “auto” ignores type qualifications from routinely writing code like this:

std::vector<int> vints{};

//fill up "vints" somehow

for(auto& elem : vints) {

//do something to each element of vints

}

However, since it was the first time I used “auto” in a new context, its type-qualifier-ignoring behavior somehow slipped my feeble mind. I hate when that happens.

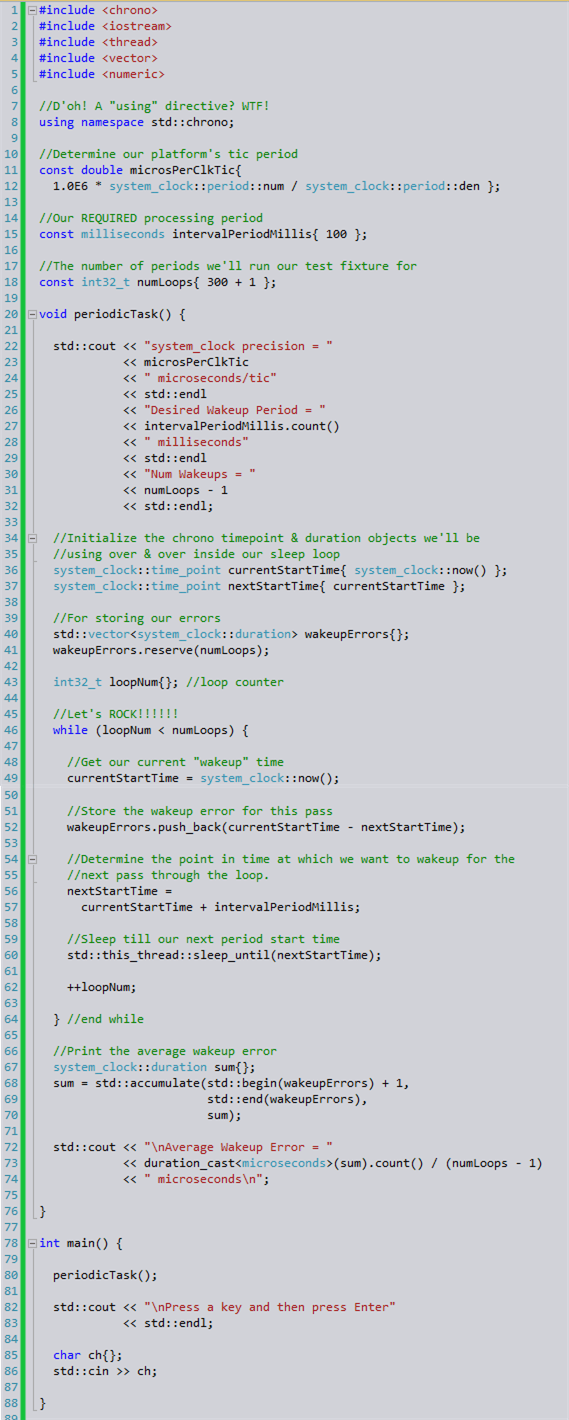

Periodic Processing With Standard C++11 Facilities

With the addition of the <chrono> and <thread> libraries to the C++11 standard library, programs that require precise, time-synchronized functionality can now be written without having to include any external, non-standard libraries (ACE, Boost, Poco, pthread, etc) into the development environment. However, learning and using the new APIs correctly can be a non-trivial undertaking. But, there’s a reason for having these rich and powerful APIs:

The time facilities are intended to efficiently support uses deep in the system; they do not provide convenience facilities to help you maintain your social calendar. In fact, the time facilities originated with the stringent needs of high-energy physics. Furthermore, language facilities for dealing with short time spans (e.g., nanoseconds) must not themselves take significant time. Consequently, the <chrono> facilities are not simple, but many uses of those facilities can be very simple. – Bjarne Stroustrup (The C++ Programming Language, Fourth Edition).

Many soft and hard real-time applications require chunks of work to be done at precise, periodic intervals during run-time. The figure below models such a program. At the start of each fixed time interval T, “doStuff()” is invoked to perform an application-specific unit of work. Upon completion of the work, the program (or task/thread) “sleeps” under the care of the OS until the next interval start time occurs. If the chunk of work doesn’t complete before the next interval starts, or accurate, interval-to-interval periodicity is not maintained during operation, then the program is deemed to have “failed“. Whether the failure is catastrophic or merely a recoverable blip is application-specific.

Although the C++11 time facilities support time and duration manipulations down to the nanosecond level of precision, the actual accuracy of code that employs the API is a function of the precision and accuracy of the underlying hardware and OS platform. The C++11 API simply serves as a standard, portable bridge between the coder and the platform.

The figure below shows the effect of platform inaccuracy on programs that need to maintain a fixed, periodic timeline. Instead of “waking up” at perfectly constant intervals of T, some jitter is introduced by the platform. If the jitter is not compensated for, the program will cumulatively drift further and further away from “real-time” as it runs. Even if jitter compensation is applied on an interval by interval basis to prevent drift-creep, there will always be some time inaccuracy present in the application due to the hardware and OS limitations. Again, the specific application dictates whether the timing inaccuracy is catastrophic or merely a nuisance to be ignored.

The simple UML activity diagram below shows the cruxt of what must be done to measure the “wake-up error” on a given platform.

On each pass through the loop:

- The OS wakes us up (via <thread>)

- We retrieve the current time (via <chrono>)

- We compute the error between the current time and the desired time (via <chrono>)

- We compute the next desired wake-up time (via <chrono>)

- We tell the OS to put us to sleep until the desired wake-up time occurs (via <thread>)

For your viewing and critiquing pleasure, the source code for a simple, portable C++11 program that measures average “wakeup error” is shown here:

The figure below shows the results from a typical program run on a Win7 (VC++13) and Linux (GCC 4.7.2) platform. Note that the clock precision on the two platforms are different. Also note that in the worst case, the 100 millisecond period I randomly chose for the run is maintained to within an average of .1 percent over the 30 second test run. Of course, your mileage may vary depending on your platform specifics and what other services/daemons are running on that platform.

The purpose of writing and running this test program was not to come up with some definitive, quantitative results. It was simply to learn and play around with the <chrono> and <thread> APIs; and to discover how qualitatively well the software and hardware stacks can accommodate software components that require doing chunks of work on fixed, periodic, time boundaries.

In case anyone wants to take the source code and run with it, I’ve attached it to the site as a pdf: periodicTask.pdf. You could simulate chunks of work being done within each interval by placing a std::this_thread::sleep_for() within the std::this_thread::sleep_until() loop. You could elevate numLoops and intervalPeriodMillis from compile time constants to command line arguments. You can use std::minmax_element() on the wakeup error samples.

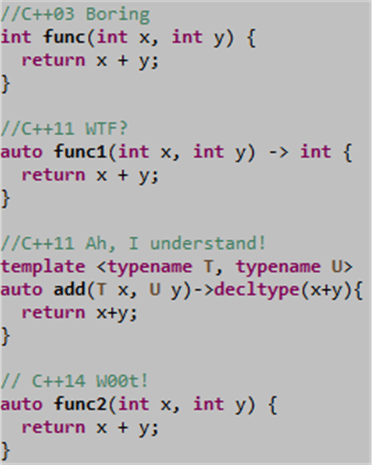

C++1y Automatic Type Deduction

The addition, err, redefinition of the auto keyword in C++11 was a great move to reduce code verbosity during the definition of local variables:

In addition to this convenient usage, employing auto in conjunction with the new (and initially weird) function-trailing-return-type syntax is useful for defining function templates that manipulate multiple parameterized types (see the third entry in the list of function definitions below).

In the upcoming C++14 standard, auto will also become useful for defining normal, run-of-the-mill, non-template functions. As the fourth entry below illustrates, we’ll be able to use auto in function definitions without having to use the funky function-trailing-return-type syntax (see the useless, but valid, second entry in the list).

For a more in depth treatment of C++11’s automatic type deduction capability, check out Herb Sutter’s masterful post on the new AAA (Almost Always Auto) idiom.

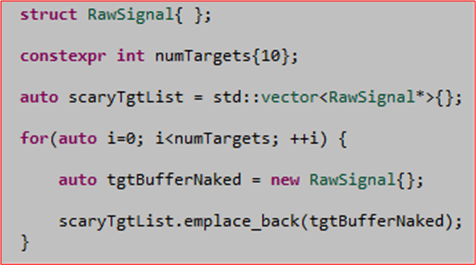

No Runtime Overhead

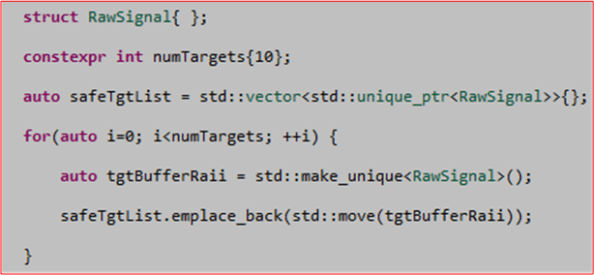

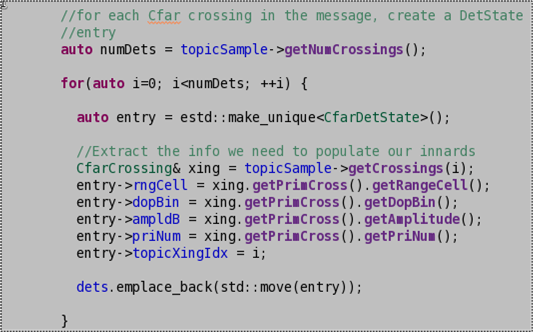

Since I have the privilege of using C++11/14 on my current project, I’ve been using the new language idioms as fast as I can discover and learn them. For example, instead of writing risky, exception-unsafe, naked “new“, code like this:

I’ve been writing code like this instead:

By using std::unique_ptr instead of a naked pointer, I don’t have to veer away from the local code I’m writing to write matching delete statements in destructors or in catch() exception clauses to prevent inadvertent memory leaks.

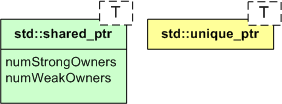

I could’ve used a std::shared_ptr (which can be copied instead of “moved“) in place of the std::unique_ptr, but std::shared_ptr is required to maintain a fatter internal state in the form of strong and weak owner counters. Unless I really need shared ownership of a dynamically allocated object, which I haven’t so far, I stick to the slimmer and more performant std::unique_ptr.

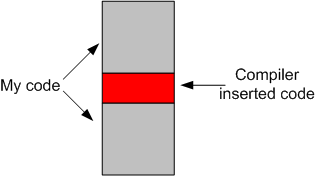

When I first wrote the std::unique_ptr code above, I was concerned that using the std::move() function to transfer encapsulated memory ownership into the safeTgtList vector would add some runtime overhead to the code (relative to the C++98/03 style of simply copying the naked pointer into the scaryTgtList vector). It is, after all, a function, so I thought it must insert some code into my own code.

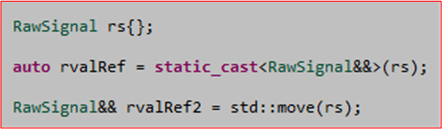

However, after digging a little deeper into my concern, I discovered (via Stroustrup, Sutter, and Meyers) that std::move() adds zero runtime overhead to the code. Its use is equivalent to performing a static_cast on its argument – which is evaluated at compile time.

As Scott Meyers stated at GoingNative13, std::move() doesn’t really move anything. It simply prepares for a subsequent real move by casting its argument from an lvalue to an rvalue – which is required for movement of an object’s innards. In the previous code, the move is actually performed within the std::vector::emplace_back() function.

Quoting Scott Meyers: “think of std::move() as an rvalue_cast“. I’m not sure why the ISO C++ committee didn’t define a new rvalue_cast keyword instead of std::move() to drive home the point that no runtime overhead is imposed, but I’d speculate that the issue was debated. Perhaps they thought rvalue_cast was too technical a term for most users?

Update 10/25/13

As I said early in the post, the code example is “like” the code I’ve been writing. The real code that triggered this post is as shown here:

Since each “entry” CfarDetState object must be uniquely intialized form it’s associated CfarCrossing object, I can’t simply insert estd::make_unique<CfarDetState>() into the emplace_back() function. All of the members of each “entry” must be initialized first. Regardless of whether I use emplace_back() or push_back(), std::move(entry) must be used as the argument of the chosen function.

It’s Definitely A Compiler Bug

Previously, I wrote a post about a potential compiler bug with the g++ compiler in the GCC 4.7.2 collection that was driving me nutz: “Uniform Initialization Failure?“. In that post, I flip-flopped between concluding whether the issue I stumbled upon was a bug or just another one of those C++ quirks that cause newbie programmers to flee in droves toward the easier-to-learn programming languages. D’oh!

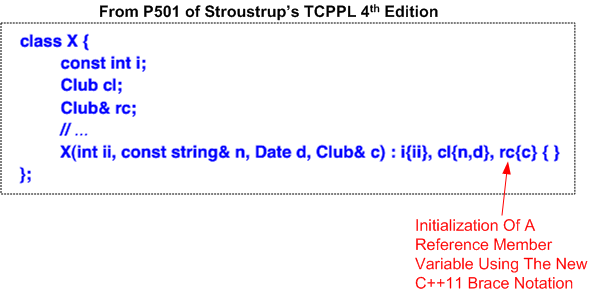

Since I wrote that post, I’ve purchased and have been studying the fourth edition of Bjarne’s TCPPL. It’s now a slam dunk. The g++ GCC 4.7.2 compiler does indeed have a bug in its implementation of C++11’s uniform initialization feature.

First, consider this Stroustrup code snippet:

Note how Bjarne “uniformly” uses braces to initialize all of class X‘s member variables – including the Club reference member variable, rc.

Next, look at the code I wrote that makes g++ 4.7.2 barf:

Note how the compiler spewed blasphemy when I tried to uniformly use braces to initialize the GccBug class’s foo and bar member variables.

Now, look at what I had to do to make the almighty compiler happy:

As you can see, I had to destroy the elegancy of uniform initialization by employing a mix of braces and old-style parenthesis to initialize the foo and bar member variables.

It’s my understanding that GCC 4.8.2 has been released and it has been deemed C++11 feature-complete. I currently don’t have it installed, but, if one of you dear readers are using it, can you please experiment with it and determine if the bug has been squashed? I have a highly coveted BD00 T-shirt waiting in the warehouse for the first person who reports back with the result.

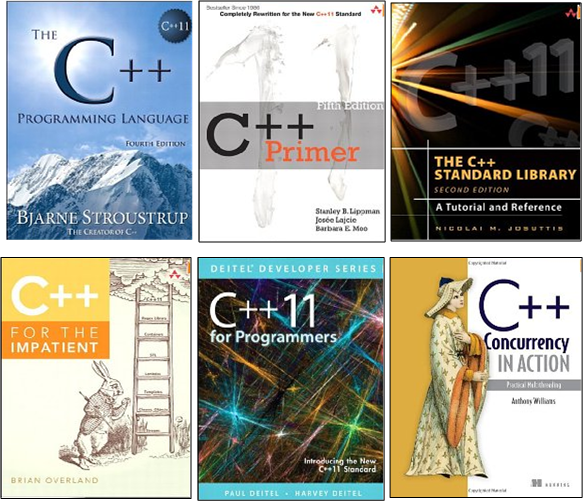

The Current Crop

There are a bazillion books on C++03 out in the wild. However, even though there are lots of pieces of C++11 material available for consumption online, there are (AFAIK) only 6 C++11 books currently available:

Lucky BD00. He has 24 X 7 e-access to all of these tomes through his Safari Books Online membership.

Note that even though he has some C++11/14 training material available for purchase on his web site, none of Scott Meyers‘ “Effective” series of C++ books has been updated yet. Fear not. The first in the series, “Effective C++11/14“, is coming to market in early 2014. The description of Scott’s upcoming GoingNative 2013 session, titled “An Effective C++11/14 Sampler“, reads as follows:

After years of intensive study (first of C++0x, then of C++11, and most recently of C++14), Scott thinks he finally has a clue. About the effective use of C++11, that is (including C++14 revisions). At last year’s Going Native, Herb Sutter predicted that Scott would produce a new version of Effective C++ in the 2013-14 time frame, and Scott’s working on proving him almost right. Rather than revise Effective C++, Scott decided to write a new book that focuses exclusively on C++11/14: on the things the experts almost always do (or almost always avoid doing) to produce clear, efficient, effective code. In this presentation, Scott will present a taste of the Items he expects to include in Effective C++11/14. If all goes as planned, he’ll also solicit your help in choosing a cover for the book.

It’s about time that Scott got a clue. 🙂

Don’t Panic!

The fourth edition of “The C++ Programming Language” weighs in at 1346 pages and 44 chapters allocated over four partitions. The end of each chapter provides a list of advisory items – yielding a grand total of 699 nuggets of general programming and C++ specific wisdom for the reader to ponder.

The figure below shows a breakdown of the behemoth book’s table of contents. The number of advisories provided in each chapter and each partition are shown on the right side.

As a temporary excursion from reading and studying and writing exploratory snippets of C++11 code, I went through all 699 items and plucked out a subset of the tidbits I found most useful. Of course, your personal list would no doubt turn out differently.

Even though it’s not on my list, my absolute favorite item of advice is the first one presented at the end of chapter 2:

D’oh! Wanna guess at how much time is needed for all to become clear? Maybe Malcolm Gladwell‘s famous “10,000 hours” isn’t enough? But that’s why I love C++. It provides an endlessly rich and deep opportunity for learning.