Archive

Efficient Abstraction

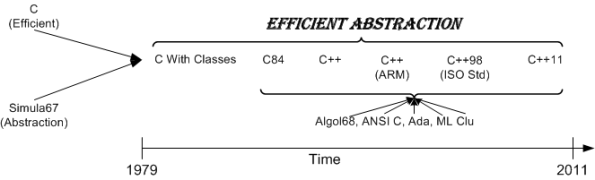

In “The Design And Evolution Of C++“, Bjarne Stroustrup presents a tree-like picture on the history of programming languages and how they’ve influenced each other. For your studying pleasure, BD00 surgically extracted and augmented a slightly more C++ focused sub-tree. In other words, BD00 committed yet another act of plagiarism. I hope you like the result.

All through the 30+ years of C++’s evolution, Bjarne and the ISO C++ standards committee have maintained a fierce and agonizing determination to march to the tune of “efficient abstraction” over theoretical purity. Adding increasing support for abstraction without sacrificing much in efficiency is more of an art than science.

D&E is not just a history book. As the figure below shows, it won one of the “Software Development Productivity Awards” from Software Development magazine waaay back when. That’s because knowing “why” and “how” the (or any) language became the way it is gives a qualitative edge to those programmers over those who just know “what” the language is.

The Lost Decade?

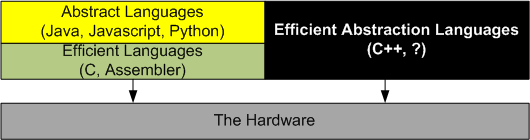

I think you’ll be hard pressed to find many knowledgeable C++ programmers who won’t admit that managed languages provide higher per-programmer productivity than native languages (because they’re easier to learn, have bigger libraries, and are not as “picky“). Likewise, I think you won’t find many “reasonable” managed language advocates who won’t admit that native language programs are more efficient (smaller and faster for a given solution) than their managed language counterparts. Having said that, take a look at this chart:

According to Herb Sutter, efficiency has(will) usurped(usurp) productivity as the dominating cost factor for software-intensive products in this decade (battery life in mobile devices, power consumption in the data center). Agree?

If you’re interested in watching the video and/or downloading Herb’s slides, here’s the link: “C++ and Beyond 2011: Herb Sutter – Why C++?“.

Range Checked Vector Access

By now, C programmers who’ve made the scary but necessary leap up to C++ should’ve gotten over their unfounded performance angst of using std::vector over raw arrays. If not, then “they” (I hate people like myself who use the term “they“) should consider one more reason for choosing std::vector over an “error prone” array when the need for a container of compact objects arises.

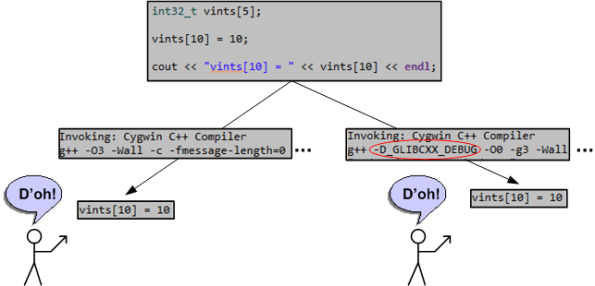

The reason is “range checked access during runtime“; and I don’t mean using std::vector::at() all over your code. Stick with the more natural std::vector::operator[]() member function at each point of use, but use -D_GLIBCXX in the compiler command line of your “Debug” build configuration. (Of course, I’m talking about the GCC g++ compiler here, but I assume other compilers have a similar #define symbol that achieves the same effect.)

The figure below shows:

- A piece of code writing into the 11th element of a std::vector that is only 5 elements long (D’oh!).

- A portion of the compiler command line used to build the Release (left) and Debug (right) configurations.

- The console output after running the code.

In contrast, here’s what you get with a bad ole array:

The unsettling aspect about the three “D’oh” result cases (unlike the sole “no D’oh” case) is that the program didn’t crash spectacularly at the point of error. It kept humming along silently; camouflaging the location of the bug and insidiously propagating the error effect further downstream in the thread of execution. Bummer, I hate when that happens.

Sandwich Dilemma

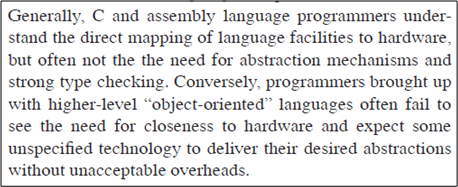

In this dated, but still relevant paper, “Evolving a language in and for the real world“, Bjarne Stroustrup laments about one of the adoption problems that (still) faces C++:

Since the overarching theme of C++ is, and always has been, “efficient abstraction“, it’s not surprising that long time efficiency zealots and abstraction aficionados would be extremely skeptical of the value proposition served up by C++. I personally know this because I arrived at the C++ camp from the C world of “void *ptr” and bit twiddling. When I first started studying C++, its breadth of coverage, feature set, and sometimes funky syntax scared me into thinking that it wasn’t worth the investment of my time to “go there“.

I think it’s easier to get C programmers to make the transition to C++ than it is to get VM-based and interpreter-based programmers to make the transition. The education, more disciplined thinking style, and types of apps written (non-business, non-web) by “close to the metal” programmers maps into the C++ mindset more naturally.

What do you think? Is C++ the best of both worlds, or the worst of both worlds?

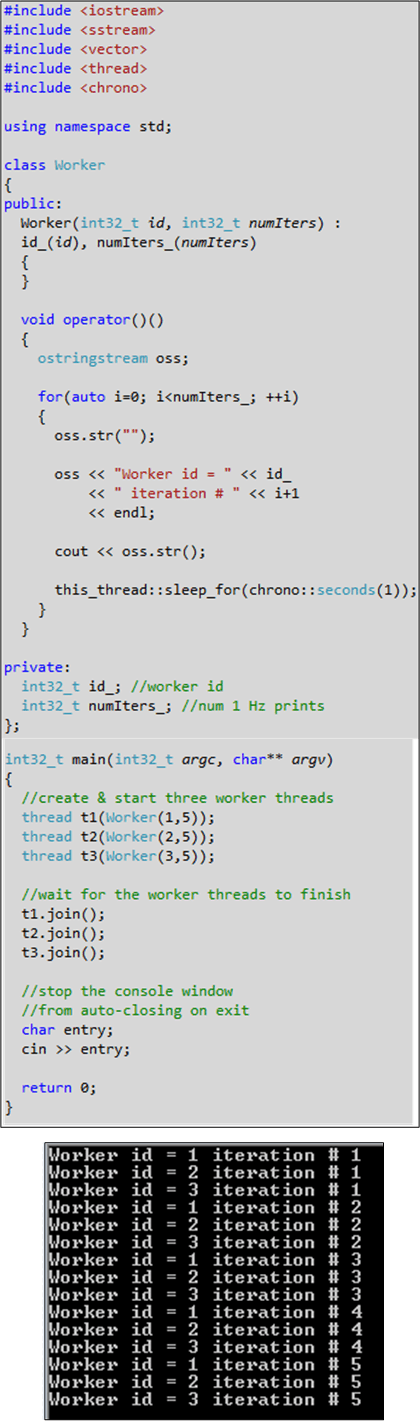

Standard, Portable C++ Concurrency

Recently, I downloaded the Microsoft Visual Studio 11 IDE Beta in order to start experimenting with some C++11 features. Lo and behold, standard and portable concurrency is now supported:

At least on Windows, there’s no need to use the Win API, Boost.Thread or ACE or any other third party library in the future to write multi-core friendly, multi-threaded C++ apps. I don’t know when GCC and/or CLANG will ship with the standard C++11 concurrency libs. Do you?

By the way, a series of quick tests verified that lambdas, strictly typed enums, auto, nullptr, std::array, std::regex, and std::atomic work. Initializer lists, raw string literals, “using” as typedef, and range-based for loops don’t work yet.

A Dearth Of Libraries

In Herb Sutter’s talk at GoingNative 2012, he opined that the biggest weakness of C++11 is its dearth of libraries; which causes programmers to waste lots of time ($$$) writing their own code to implement mundane functionality like XML parsing, cryptography, networking/sockets, thread-safe containers (<- I’ve had to spend quite a bit of time doing this!), serialization, etc.

Using language and library specification page counts, Herb started out by showing the progressive growth of C and C++ over time:

Next, Herb presented this eye-popping chart of relative library size for C++11, .NET, and Java:

Yes, that’s C++11 down in those tiny blue boxes. WTF! Note that the core language specifications on the left side of the chart are roughly the same size.

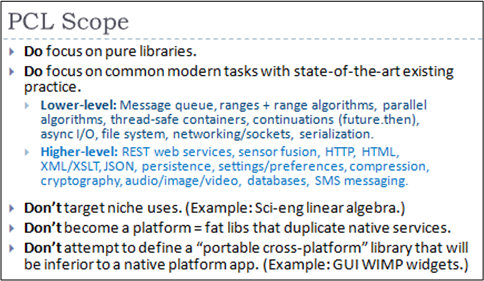

To address the issue, Herb proposed the formation of a an open-source Portable C++ Libraries (PCL) organization with the following guiding principles:

Herb also addressed the issue of how the PCL would interact with the C++ standards committee with this chart:

Basically, the PCL would serve as a front end vetter and integrator of library submittals in order to unburden the committee from the responsibility and allow it to concentrate more on tricky core language features (concepts, modules, static if, etc). The C++ committee would serve as the final fine-grained scrutinizer and approver of library additions to the language. In practice, libraries like poco and Qt could be shipped with every standards-compliant C++ compiler in the future.

I think Herb’s idea is a good one and I hope it blossoms into the real deal. How about you? What do you think?

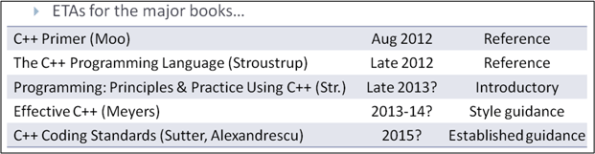

Broken Books

With the addition of features like auto, initializer lists, lambdas, and smart pointers, a lot of C++98 programming idioms and guidance have become obsolete now that C++11 is here. Thus, as Herb Sutter said at GoingNative 2012, a boatload of code examples in the best C++ books are now “broken“.

As a result, new and revamped versions of the books will take awhile to become available. Here’s Herb’s “estimated time of arrival” for several stalwart books:

In the meantime, you can feast your eyes on, and feed the left side of your brain with, these links:

- Bjarne Stroustrup’s C++11 FAQ page

- Wikipedia C++11

- Scott Meyers Overview Of C++11

- C++11 Features To GCC Compiler Map

- C++ Standards Committee Home Page

- GoingNative 2012

- C++11 Features in Visual C++ 11

- Clang Compiler C++11 Support

- Writing Modern C++ Code (Herb Sutter)

Do you know of any other good links to add to this post?

Vectors And Lists

In C++ programming, everybody knows that when an application requires lots of dynamic insertions into (and deletions from) an ordered sequence of elements, a linked list is much faster than a vector. Err, is it?

Behold the following performance graph that Bjarne Stroustrup presented during his keynote speech at “Going Native 2012“:

So, “WTF is up wit dat?”, you ask. Here’s what’s up wit dat:

The CPU load happens to be dominated by the time to traverse to the insertion/deletion point – and KNOT by the time to actually insert/delete the element. So, you still yell “WTF!“.

The answer to the seeming paradox is “compactness plus hardware cache“. If you’re not as stubborn and full of yourself as BD00, this answer “may” squelch the stale, flat-earth mindset that is still crying foul in your brain.

Since modern CPUs with big megabyte caches are faster at moving a contiguous block of memory than traversing a chain of links that reside outside of on-chip cache and in main memory, the results that Bjarne observed during his test should start to make sense, no?

To drive his point home, Mr. Stroustrup provided this vector-list example:

In addition to consuming more memory overhead, the likelihood that all the list’s memory “pieces” reside in on-chip cache is low compared to the contiguous memory required by the vector. Thus, each link jump requires access to slooow, off-chip, main memory.

The funny thing is that recently, and I mean really recently, I had to choose between a list and a vector in order to implement a time ordered list of up to 5000 objects. Out of curiosity, I wrote a quick and dirty little test program to help me decide which to use and I got the same result as Bjarne. Even with the result I measured, I still chose the list over the vector!

Of course, because of my entrenched belief that a list is better than a vector for insertion/deletion heavy situations, I rationalized my unassailable choice by assuming that I somehow screwed up the test program. And since I was pressed for time (so, what else is new?), I plowed ahead and coded up the list in my app. D’oh!

Update 4/21/13: Here’s a short video of Bjarne himself waxing eloquent on this unintuitive conclusion: “linked list avoidance“.

Ghastly Style

In Bjarne Stroustrup‘s keynote speech at “Going Native 2012“, he presented the standard C library qsort() function signature as an example of ghastly style that he’d wish programmers and (especially) educators would move away from:

Bjarne then presented an alternative style, which not only yields cleaner and less error prone code, but much faster performance to boot:

Bjarne blames educators, who want to stay rooted in the ancient dogma that “low level coding == optimal efficiency“, for sustaining the unnecessarily complex “void star” mindset that still pervades the C and C++ programming population.

Because they are taught the “void star” way of programming by teaching “experts“, and code of that ilk is ubiquitous throughout academia and the industry, newbie C and C++ programmers who don’t know any better strive to produce code of that “quality“. The innocent thinking behind the motivation is: “that’s the way most people write code, so it must be good and kool“.

I can relate to Mr. Stroustrup’s exasperation because it took perfect-me a long time to overcome the “void star” mental model of the world. It was so entrenched in my brain and oft practiced that I still unconsciously drift back into my old ways from time to time. It’s like being an alcoholic where constant self-vigilance and an empathic sponsor are required to keep the demons at bay. Bummer.

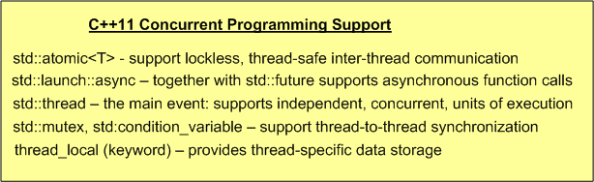

Concurrency Support

Assuming that I remain a lowly, banana-eating programmer and I don’t catch the wanna-be-uh-manager-supervisor-director-executive fever, I’m excited about the new features and library additions provided in the C++11 standard.

Specifically, I’m thrilled by the support for “dangerous” multi-threaded programming that C++11 serves up.

For more info on the what, why, and how of these features and library additions, check out Scott Meyers’ pre-book training package, Anthony Williams’ new book, and Bjarne’s C++11 FAQ page.