Archive

Two Hundred And Fifty To Zero

Whoo Hoo! Since March of 2009, I’ve posted just over 250 BS blog entries. However, my labor of love has led to zero supplemental income. As they say (whoever the ubiquitous they are), “don’t quit your day job“. That’s OK, because I love my day job. Since the vast majority of the people that I work with, and for, are good and decent people that give their best every day, I’m a happy camper.

Scalability: The Next Buzzword

Since I’m currently in the process of trying to help a team re-design an existing software-intensive system to be more scalable, the title of this book caught my eye:

It’s just my opinion (and you know what “they” say about opinions) but stay away from this stinker. All the authors want to do is to jump on the latest buzzword of “scalability” and make tons of money without helping anybody but themselves.

Check this self-serving advertisement out:

“The Art of Scalability addresses these issues by arming executives, engineering managers, engineers, and architects with models and approaches to scale their technology architectures, fix their processes, and structure their organizations to keep “scaling” problems from affecting their business and to fix these problems rapidly should they occur.”

Notice how they try to cover the entire hierarchical corpo gamut from bozo managers at the peak of the pyramid down to the dweebs in the cellar to maximize the return on their investment. Blech and hawk-tooey.

BTW, I actually did waste my time by reading the first BS chapter. The rest of the book my be a Godsend, but I’m not about to invest my time trying to figure out if it is.

BTW, I actually did waste my time by reading the first BS chapter. The rest of the book my be a Godsend, but I’m not about to invest my time trying to figure out if it is.

Unscalable Orgs

My friend Byron Davies sent me a link to this 3 minute MIT Media Lab video in which associate Media Lab Director Andy Lippman challenges us to recognize four common flaws plaguing all of our institutions. Obtaining a new awareness and understanding of the plague is the first step toward meaningful redesign.

According to Lippman, the top four reasons for organizational decline are:

- They’re out of scale – they’ve grown too big to perform in accordance with their original design

- They’re monocultures – they all act the same

- They’re opaque – nobody from within or without understands how they freakin’ work

- They’ve lost their original mission – A summation of the previous three reasons.

Because of the pervasive institutional obsession for growth, Lippman seems to think that solving the scaling problem through the development of nested communities is the most promising strategy for halting the decline.

Spoiled And Lazy; Hungry And Energetic

A few years ago, I read an opinion piece regarding the demise of the US auto industry. The author stated that because they were spoon fed boatloads of money by the US government to design and build military hardware during WWII, the car companies morphed into spoiled and lazy sloths; they stopped innovating on their own nickel. Unless a sugar daddy (like the US government) was going to externally subsidize the effort, they weren’t gonna open the company coffers to develop new products or vastly improve their existing ones. Because of this overly conservative mindset (and the poo pooing away of Deming’s quality movement), the Japanese eventually blew right by the big three – even though their nation was decimated by the war and they had to start from scratch.

The same danger applies today, every day, to every company that builds things, especially big things, for government orgs. Understandably, since creating and continuously improving big complex systems requires big investments and big scary risks to be overcome, companies are loathe to pour money into what may eventually turn out to be an infinite rat hole. However, if all the competitors in the market space have the same welfare mindset, then no one will sprint out ahead of the pack and all participants may still prosper – until money gets tight. When the external dollar stream slows to a trickle, those (if any) competitors who’ve boldly invested in the future and successfully transformed their investments into product improvements and new product portfolio additions, rise to the top. It’s the hungry and energetic, not the spoiled and lazy, that continuously prosper through good times and bad.

Is your company spoiled and lazy, or hungry and energetic? If it’s the former, what actions does your company take when tough economic times emerge and the money stream slows?

Sole Source

When a customer awards a vendor a contract without considering bids from other competitors, it is deemed a sole source victory. There are two ways to look at “sole source” contracts:

- The customer loves you

- The customer hates you

If you’ve done a great job providing a product that unobtrusively solves a customer’s problem, then that customer will love your company. Hence, if the “rules” allow it, that customer will shower you with follow on sole source contracts for more copies and variants of the product.

If your product sux but it is inextricably and pervasively intertwined within the customer’s day-to-day operations, then your customer may hate you. However, since it would cost a ton of money and time to rip out and replace your junk with someone else’s junk, the customer may still shower you with follow on sole source contracts.

Regardless of which reality is true, corpo hierarchs will always attribute sole source contract awards to love.

Fifty-Fifty

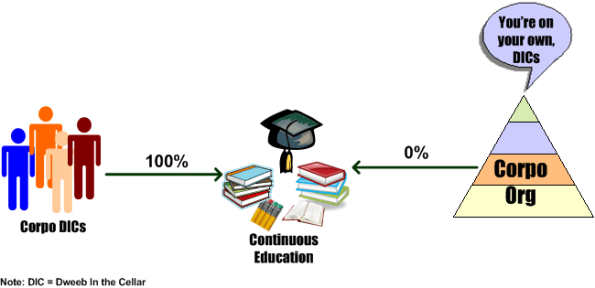

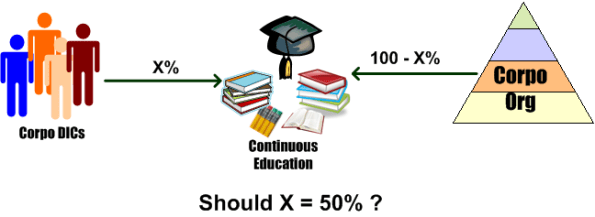

Because of the current economic environment, lots of recycled articles (take charge) regarding continuous education have appeared. Almost every one of them dispenses the same advice: “only you are responsible for continuously educating yourself and keeping your skills up to date”. Of course this is obviously true, but what about an employer’s duty to its stakeholders for ensuring that its workforce has the necessary training and skills to keep the company viably competitive in a rapidly changing landscape? Because of this duty, shouldn’t the responsibility be shared? What about fifty-fifty?

There are at least two ways that corpo managements (if they aren’t so self-absorbed that they’re actually are smart enough to detect the need) react to the need for continuing education of the people that produce its products and provide its services.

- Hire externally to acquire the new skills that it needs

- Invest internally to keep its workforce in synch with the times

Clueless orgs do neither, average orgs do number 1, above average orgs do 2, and great orgs do 1 and 2. Hiring externally can get the right skills in the right place faster and cheaper in the short run, but it can be much riskier than investing internally. Is your hiring process good enough to consistently weed out bozos, especially those that will be placed in positions that require leading people? If it’s a new skill that you require, how can your interviewers (most of whom, by definition, won’t have this new skill) confidently and assuredly determine if candidates are qualified? As everyone knows, face-to-face interviews, references and resumes can be BS smokescreens.

If external competitive pressures require a company to acquire deep, vertical and highly specialized skills, then hiring or renting from the outside may be the right way to go. It may be impractical and untimely to try and train its workforce to acquire knowledge and skills that require long term study. If you have a bunch of plumbers and you need an electrician to increase revenue or execute more efficiently, then it may be more cost effective and timely to hire a trained electrician than to train your plumbers to also become electricians (or it may not).

Which strategy does your corpocracy predominantly use to stay relevant? Number 1, number 2, both, or neither? If neither, why do you think that is the case? No cash, no will, neither?

What Happened To Ross?

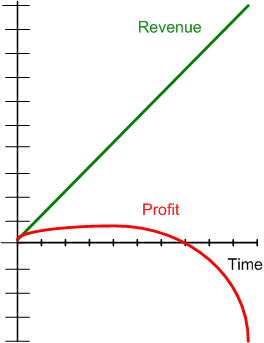

In the ideal case, an effectively led company increases both revenues and profits as it grows. The acquisition of business opportunities grows the revenues, and the execution of the acquired business grows the profits. It is as simple as that (I think?).

ROS (Return On Sales) is a common measure of profitability. It’s the amount of profit (or loss) that remains when the cost to execute some acquired business is subtracted from the revenue generated by the business. ROS is expressed as a percentage of revenue and the change in ROS over time is one indicator of a company’s efficiency.

The figure below shows the financial performance of a hypothetical company over a 10 year time frame. In this example, revenues grew 100% each year and the ROS was skillfully maintained at 50% throughout the 10 year period of performance. Steady maintenance of the ROS is “skillful” because as a company grows, more cost-incurring bureaucrats and narrow-skilled specialists tend to get added to manage the growing revenue stream (or to build self-serving empires of importance that take more from the org than they contribute?).

For comparison, the figure below shows the performance of a poorly led company over a 10 year operating period. In this case the company started out with a stellar 50% ROS, but it deteriorated by 10% each subsequent year. Bummer.

So, what happened to ROS? Who was asleep at the wheel? Uh, the executive leadership of course. Execution performance suffered for one or (more likely) many reasons. No, or ineffective, actions like:

- failing to continuously train the workforce to keep them current and to teach them how to be more productive,

- remaining stationary and inactive when development and production workers communicated ground-zero execution problems,

- standing on the sidelines as newly added “important ” bureaucrats and managers piled on more and more rules, procedures, and process constraints (of dubious added-value) in order to maintain an illusion of control,

- hiring more and more narrow and vertically skilled specialists that increased the bucket brigade delays between transforming raw inputs into value-added outputs,

may have been the cause for the poor performance. Then again, maybe not. What other and different reasons can you conjure up for explaining the poor execution performance of the company?

Lesson Unlearned

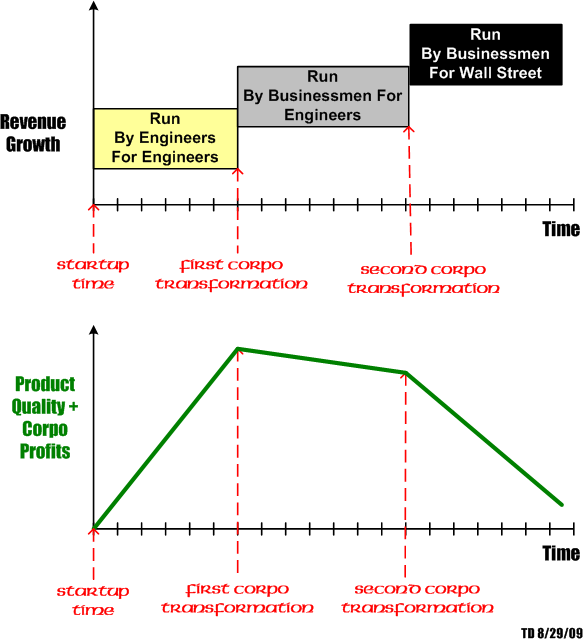

Whoo hoo! We finally said screw it, we overcame our fears, and we mustered enough courage and determination to say “hasta la vista baby” to the stifling corpo citadels that we were shackled to. We huddled together, we created a flexible plan, we busted the cuffs, we scaled the prison wall, and holy crap; we actually freakin’ succeeded. We started our own company. And it’s growing. And our people feel useful and appreciated. And life is good. Ahhhhhhh!

Well duh, of course we need to track and manage revenues and costs, but in our company, unlike the herd we left behind (mooo!), those two obviously important metrics will always take a back seat to taking care of, and leading the people who create, develop, build, and sustain our product portfolio. Because we’ve personally experienced living in the quagmire, we’ve learned our lesson. We get “it” and we’ll never forget “it”. There’s no way, we mean no way, that we’re not gonna end up like our previous corpo hierarchs, who managed to turn it all backasswards – numbers first and people second (even though they innocently espoused the opposite).

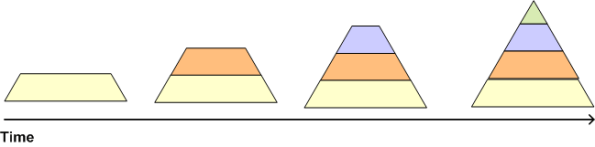

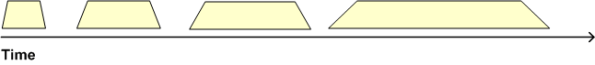

Ummmm, yeah…… right. Check out the two parallel timelines below that purport to track the growth and maturity of a hypothetical startup company in the technology industry. I honestly don’t know squat, but I assert that the story reflected by the graphical depiction below is pervasive and ubiquitous, especially throughout the western world. If you could possibly be delirious enough to resonate with the content of this blarticle, then you may interpret the situation as a hopelessly sad state of affairs. Believe it or not, I interpret the situation as neither good nor bad. It just is what it is.

Hierarchical Growth

I’m currently in the process of reading Donella Meadows’s Thinking In Systems. Donella says that successful hierarchical systems grow from the bottom up, one layer at a time.

In the case of a human-made system of humans, as an assembled group of people becomes successful at what it does, it starts growing horizontally. The group finds a way to extract what it needs to sustain and grow itself (like money in exchange for products and services) from its surrounding environment.

In the case of a human-made system of humans, as an assembled group of people becomes successful at what it does, it starts growing horizontally. The group finds a way to extract what it needs to sustain and grow itself (like money in exchange for products and services) from its surrounding environment.

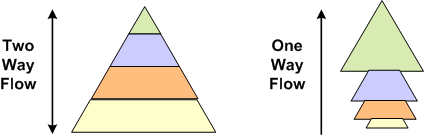

In order to keep the group aligned and coordinated, the next higher level is formed from a small sub-group within the first level. Both levels feed each other in a mutually beneficial relationship and the organization keeps growing sideways. At a certain point, the second level becomes wide enough to require a third level to keep it synchronized with the group’s overall organizational goals. As growth continues, more and more layers are needed to keep the overall system from diverging from its true purpose.

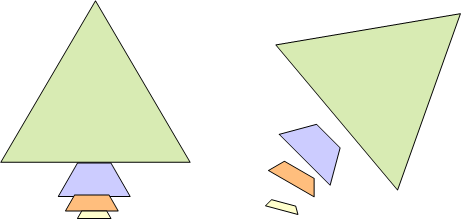

At some unpredictable point in time, a strange and seemingly irrational inversion starts taking place as growth continues. The smaller, but higher layers in the hierarchy start consuming a more disproportionate share of the fruits of the organizational effort. The original, mutually beneficial, two way relationship transforms into an unbalanced one way relationship that is strangely accepted and taken for granted by everyone at all levels.

As a result of the imbalance, the bottom layers begin to atrophy from a lack of nourishment. As the one way upward flow of nourishment continues, the weight of the top layers increases and the strength of the lower layers decreases. In the worst case, the organization loses its balance and comes crashing to earth in a disintegrated mess.

In the early stages of growth, everyone in the organization fully understands that each successive layer is put in place to take care of the layer below it, and vice versa. When this understanding gets lost, all is lost. It’s just a matter of time until disaster strikes. Can the process be reversed? Sure it can, by restoring the balance and never losing sight of why the upper layers were created in the first place.

Three Things

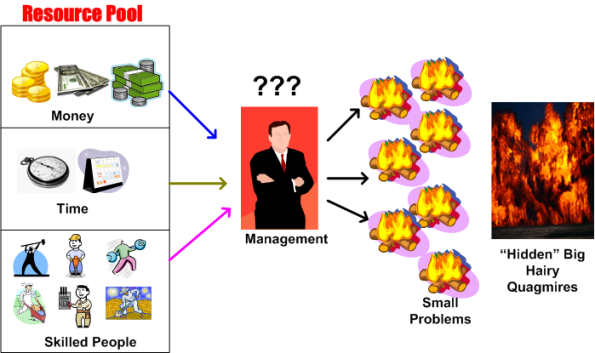

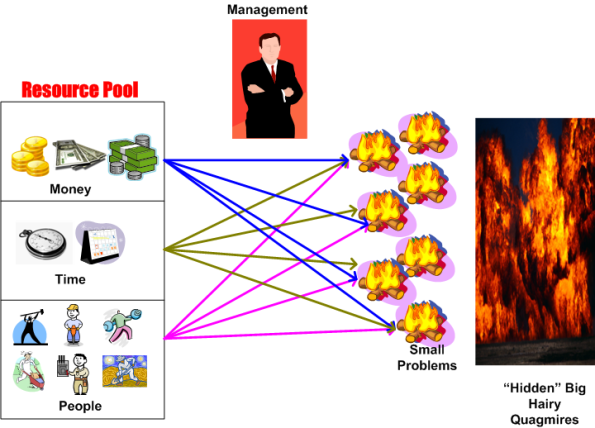

Three things: people, money, and time. These three interdependent resource types are the weapons that managers can deploy to create and sustain wealth for an organization. Managers are tasked with the challenge of judiciously apportioning these raw resources to the creation and sustainment of value-added products and services that solve customer problems. In addition to the creation and sustainment of products and services, the difficulty of continuously aligning and steering large groups of people toward the goals of growth and increasing profitability causes problem “fires” to be ignited within the corpo citadel. Bloated processes and warring factions are just two examples of the infinite variety of “pop up” fires that impede growth and profitability.

Left unchecked, internal brush fires always grow and merge into paradoxically massive, but hidden, forest fires that consume valuable resources. Brush fires feed on neglect and ignorance. Instead of creating wealth and continuously satisfying the external customer base, the three resource pools get exhausted by constantly being allocated to extinguishing internal fires.

Unless managers can “see” the growing fires, one or more massive fireballs can burn the organization to the ground. So, how can managers prevent massive fireballs from consuming would-be profits and customer goodwill? By constantly listening to, and investigating, and smartly acting on, the concerns of their people and their customers. Just listening is not enough. Just investigating is not enough. Just listening and investigating is not enough. Just listening and investigating and ineffective action is not enough. Listening, investigating, and effective action are all required.