Archive

PAYGO II

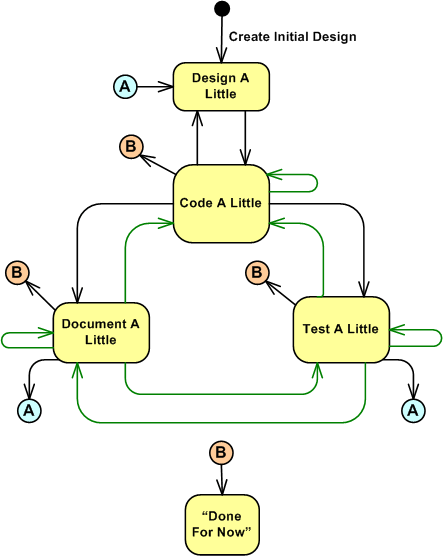

PAYGO stands for “Pay As You Go“. It’s the name of the personal process that I use to create or maintain software. There are five operational states in PAYGO:

- Design A Little

- Code A Little

- Test A Little

- Document A Little

- Done For Now

Yes, the fourth state is called “Document A Little“, and it’s a first class citizen in the PAYGO process. Whatever process you use, if some sort of documentation activity is not an integral part of it, then you might be an incomplete and one dimensional engineer, no?

“…documentation is a love letter that you write to your future self.” – Damian Conway

The UML state transition diagram below models the PAYGO states of operation along with the transitions between them. Even though the diagram indicates that the initial entry into the cyclical and iterative PAYGO process lands on the “Design A Little” state of activity, any state can be the point of entry into the process. Once you’re immersed in the process, you don’t kick out into the “Done For Now” state until your first successful product handoff occurs. Here, successful means that the receiver of your work, be it an end user or a tester or another programmer, is happy with the result. How do you know when that is the case? Simply ask the receiver.

Notice the plethora of transition arcs in the diagram (the green ones are intended to annotate feedback learning loops as opposed to sequential forward movements). Any state can transition into any other state and there is no fixed, well defined set of conditions that need to be satisfied before making any state-to-state leap. The process is fully under your control and you freely choose to move from state to state as “God” (for lack of a better word) uses you as an instrument of creation. If clueless STSJ PWCE BMs issue mindless commands from on high like “pens down” and “no more bug fixing, you’re only allowed to write new code“, you fake it as best you can to avoid punishment and you go where your spirit takes you. If you get caught faking it and get fired, then uh….. soothe your conscience by blaming me.

The following quote in “The C++ Programming Language” by mentor-from-afar Bjarne Stroustrup triggered this blog post:

In the early years, there was no C++ paper design; design, documentation, and implementation went on simultaneously. There was no “C++ project” either, or a “C++ design committee.” Throughout, C++ evolved to cope with problems encountered by users and as a result of discussions between my friends, my colleagues, and me. – Bjarne Stroustrup

When I read it on my Nth excursion through the book (you’ve made multiple trips through the BS book too, no?), it occurred to me that my man Bjarne uses PAYGO too.

Say STFU to all the mindlessly mechanistic processes from highly-credentialed and well-intentioned luminaries like Watts Humphrey’s PSP (because he wants to transform you into an accountant) and your mandated committee corpo process group (because the chances are that the dudes who wrote the process manuals haven’t written software in decades) and the TDD know-it-alls. Embrace what you discover is the best personal development process for you; be it PAYGO or whatever personal process the universe compels you to embrace. Out of curiosity, what process do you use?

If you’re interested in a higher level overview of the personal PAYGO process in the context of other development processes, you can check out this previous post: PAYGO I. And thanks for listening.

BS Design

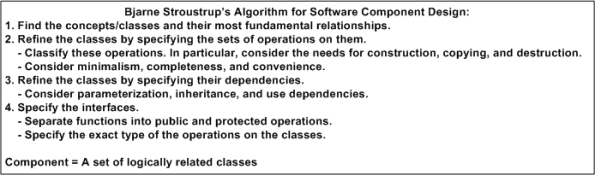

Sorry, but I couldn’t resist naming the title of this post as it is written. However, despite what you may have thought on first glance, BS stands for dee man, Bjarne Stroustrup. In chapter 23 of “The C++ Programming Language“, Bjarne offers up this advice regarding the art of mid-level design:

To find out the details of executing each iterative step in the while(not_done){} loop, go buy the book. If C++ is your primary programming language and you don’t have the freakin’ book, then shame on you.

Bjarne makes a really good point when he states that his unit of composition is a “component”. He defines a component as a cluster of classes that are cohesively and logically related in some way.

A class should ideally map directly into a problem domain concept, and concepts (like people) rarely exist in isolation. Unless it’s a really low level concrete concept on the order of a built in type like “int”, a class will be an integral player in a mini system of dynamically collaborating concepts. Thinking myopically while designing and writing classes (in any language that directly supports object oriented design) can lead to big, piggy classes and unnecessary dependencies when other classes are conceived and added to the kludge under construction – sort of like managers designing an org to serve themselves instead of the greater community. 🙂

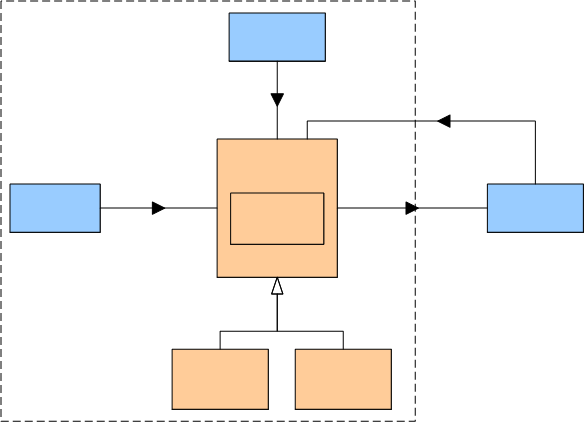

The figure below shows “revision 0” of a mini system of abstract classes that I’m designing and writing on my current project. The names of the classes have been elided so that I don’t get fired for publicly disclosing company secrets. I’ve been architecting and designing software like this from the time I finally made the painful but worthwhile switchover to C++ from C.

The class diagram is the result of “unconsciously” applying step one of Bjarne’s component design process. When I read Bjarne’s sage advice it immediately struck a chord within me because I’ve been operating this way for years without having been privy to his wisdom. That’s why I wrote this blowst – to share my joy at discovering that I may actually be doing something right for a change.

C++ Naming Conventions

For grins, I perused a few books written by several C++ mentors that I respect and admire. I was interested in the naming conventions that they personally use when writing code. Here are the results.

Scott Meyers (Effective C++):

class names – class PhoneBook {};

member function names – void addPhoneNumber(const std::string& pn);

member attribute names – std::string theAddress;

Note: no annotation to distinguish class member attributes from local function variables.

Bjarne Stroustrup (The C++ Programming Language):

“I consider the CamelCodingStyle of identifiers “pug ugly” and strongly prefer underscore_style as cleaner and inherently more readable, and many people agree. On the other hand, many reasonable people disagree.“

class names – class Phone_book {};

member function names – void add_phone_number(const std::string& pn);

member attribute names – std::string the_address;

Note: no annotation to distinguish class member attributes from local function variables.

Herb Sutter and Andrei Alexandrescu (C++ Coding Standards):

class names – class PhoneBook {};

member function names – void AddPhoneNumber(const std::string& pn);

member attribute names – std::string theAddress_;

Note: they use post-underscores to distinguish class member attributes from local function variables (int clientName_; //is a class member)

When I’m not constrained by a specific naming standard, I use this one:

class names – class PhoneBook {};

member function names – void add_phone_number(const std::string& pn);

member attribute names – std::string the_address_;

Note: Like Herb & Andrei, I use post-underscores to distinguish class member attributes from local function variables (int client_name_; //is a class member).

Strongly Typed

In “Hackers and Painters“, one of my favorite essayists and modern day renaissance men, Paul Graham, states his disdain for strongly typed programming languages. The main reason is that he doesn’t like to be scolded by mindless compilers that handcuff his creativity by enforcing static type-checking rules. Being a C++ programmer, even though I love Paul and understand his point of view, I have to disagree. One of the reasons I like working in C++ is because of the language’s strong type checking rules, which are enforced on the source code during compilation. C++ compilers find and flag a lot of my programming mistakes prior to runtime <- where finding sources of error can be much more time consuming and frustrating.

Driven by “a fierce determination not to impose a specific one size fits all programming style” on programmers, Bjarne Stroustrup designed C++ to allow programmers to override the built-in type system if they consciously want to do so. By preserving the old C style casting syntax and introducing new, ugly C++ casting keywords (static_cast, dynamic_cast, etc) that purposefully make manual casts stick out like a sore thumb and easily findable in the code base, a programmer can legally subvert the type system.

C++ gets trashed a lot by other programming language zealots because it’s a powerful tool with a rich set of features and it supports multiple programming styles (procedural, abstract data types, object-oriented, generic) instead of just one “pure” style. Those attributes, along with Bjarne’s empathy with the common programmer, are exactly why I love using C++. How about you, what language(s) do and don’t you like? Why?

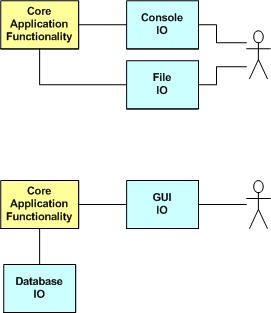

Console And Files First, GUI And Database Last

Adding Database IO and GUI IO to a program ratchets up it’s complexity, and hence development time, immensely. In “Programming: Principles and Practice Using C++“, Bjarne Stroustrup recommends designing and writing your program to do IO over the console and filesystem first, and then adding GUI IO and database IO later. And only if you have to.

Eliminating, or at least delaying, GUI and database IO forces you to focus on getting the internal application design right early. It also helps to keep you from tangling the GUI IO and database IO code with your application code and creating an unmaintainable ball of mud. Thirdly, the practice also makes testing much simpler than trying to write and debug the whole quagmire at once. Good advice?

Islands Of Sanity

Via InformIT: Safari Books Online – 0201700735 – The C++ Programming Language, Special Edition, I snipped this quote from Bjarne Stroustrup, the creator of the C++ programming language:

“AT&T Bell Laboratories made a major contribution to this by allowing me to share drafts of revised versions of the C++ reference manual with implementers and users. Because many of these people work for companies that could be seen as competing with AT&T, the significance of this contribution should not be underestimated. A less enlightened company could have caused major problems of language fragmentation simply by doing nothing.”

There are always islands of sanity in the massive sea of corpocratic insanity. AT&T’s behavior at that time during the historical development of C++ showed that they were one of those islands. Is AT&T still one of those rare anomalies today? I don’t have a clue.

Another Bjarne quote from the book is no less intriguing:

“In the early years, there was no C++ paper design; design, documentation, and implementation went on simultaneously. There was no “C++ project” either, or a “C++ design committee.” Throughout, C++ evolved to cope with problems encountered by users and as a result of discussions between my friends, my colleagues, and me.”

WTF? Direct communication with users? And how can it be possible that no PMI trained generic project manager or big cheese executive was involved to lead Mr. Stroustrup to success? Bjarne should’ve been fired for not following the infallible, proven, repeatable, and continuously improving, corpo product development process. No?

No BS, From BS

You certainly know what the first occurrence of “BS” in the title of this blarticle means, but the second occurrence stands for “Bjarne Stroustrup”. BS, the second one of course, is the original creator of the C++ programming language and one of my “mentors from afar” (it’s a good idea to latch on to mentors from afar because unless your extremely lucky, there’s a paucity of mentors “a-near”).

I just finished reading “The Design And Evolution of C++” by BS. If you do a lot C++ programming, then this book is a must read. BS gives a deeply personal account of the development of the C++ language from the very first time he realized that he needed a new programming tool in 1979, to the start of the formal standardization process in 1994. BS recounts the BS (the first one, of course) that he slogged through, and the thinking processes that he used, while deciding upon which features to include in C++ and which ones to exclude. The technical details and chronology of development of C++ are interesting, but the book is also filled with insightful and sage advice. Here’s a sampling of passages that rang my bell:

“Language design is not just design from first principles, but an art that requires experience, experiments, and sound engineering trade-offs.”

“Many C++ design decisions have their roots in my dislike for forcing people to do things in some particular way. In history, some of the worst disasters have been caused by idealists trying to force people into ‘doing what is good for them'”.

“Had it not been for the insights of members of Bell Labs, the insulation from political nonsense, the design of C++ would have been compromised by fashions, special interest groups and its implementation bogged down in a bureaucratic quagmire.”

“You don’t get a useful language by accepting every feature that makes life better for someone.”

“Theory itself is never sufficient justification for adding or removing a feature.”

“Standardization before genuine experience has been gained is abhorrent.”

“I find it more painful to listen to complaints from users than to listen to complaints from language lawyers.”

“The C++ Programming Language (book) was written with the fierce determination not to preach any particular technique.”

“No programming language can be understood by considering principles and generalizations only; concrete examples are essential. However, looking at the details without an overall picture to fit them into is a way of getting seriously lost.”

For an ivory tower trained Ph.D., BS is pretty down to earth and empathic toward his customers/users, no? Hopefully, you can now understand why the title of this blarticle is what it is.