Obsoleted By Modernity

While sifting through my desk at work, I stumbled upon a gadget that triggered some fond memories:

Do you know what it is? It’s a Royal Mark page embosser; a meaty and well built device that I used for many years until the onslaught of modernity made it obsolete.

Before the advent of e-books and safaribooksonline.com, I used to buy lots of “real” technical books. I would stamp them with my trusty Royal Mark embosser and stick them in my bookcase as soon as they arrived. But alas, since I don’t buy many dead-tree books anymore, I haven’t used my lovely Royal Marker in decades.

What gadgets or tools did you use heavily in the past, but have been obsoleted by newer technology? If you’re young enough, probably none; but eventually you will.

The Repo Of Shared Understanding

Documentation can be organized, structured, archived, searched. Verbal communications can’t.

Check out these two communication system configurations for developing software.

The system on the left, which depends (almost) solely on face-to-face collaboration, is the “agile” way. The system on the right, designed around a living, breathing, Repository Of Shared Understanding (ROSU) and supplemented by face-to-face conversation, is the “traditional” configuration.

As the previous paragraph implies, “agile” doesn’t recommend no documentation generation. It simply relegates the practice of document creation to the back of the bus. The idea, premised on the myth that documentation isn’t a required deliverable (in my industry it is) and the truth that programmers hate to write anything but code, is to supplement face-to-face communion with temporary, discardable, napkin scribblings and incomprehensible whiteboard snapshots.

Which system configuration do you think is more scalable? Which is more effective for long-lived, software-intensive products? Which do you think is better, more accommodating, for onboarding future team members? Which do you think is more effective for investigating/understanding/debugging system level failures (not unit level failures)?

Agilists will often bolster their “minimal documentation” approach with the assertion that requirements and design documents become obsolete as soon as the ink dries. Well yeah, if the team doesn’t continuously update its ROSU, then they’re right. But why is it such a big deal to keep the ROSU in synch with the code? The big deal is that it’s tough to sustain the discipline and resolve to so.

A Blast From The Past

One of the first from-scratch products I ever worked on was named “BEXR” (Beacon Extractor & Recorder, pronounced “Beck’s-uhr“). I proposed the name BEVR (Beacon Evaluation & Video Recorder, pronounced “beaver“), but it was shot down by the marketing department immediately for who knows why 🙂

BEXR was a custom hardware and software combo that connected to the raw, low-level, return signals received by FAA secondary surveillance radars from aircraft-based transponders. The product allowed FAA maintenance personnel to observe and evaluate the quality of radar and transponder signals in real-time – much like a specialized oscilloscope. In addition, it supported recording and playback capabilities for off-site analysis.

Despite it’s utility to the FAA, BEXR was politically controversial. Since non-conforming aircraft transponders were relatively expensive to fix and reinstall, owners of small aircraft did not like being “spied upon“. They did not want to know if their equipment was out-of-spec. Thus, BEXR’s mission was limited to troubleshooting only radar issues.

BEXR was comprised of two, custom-designed, 16 bit, PC-AT bus cards. They were packaged in a portable PC that was carted to/from the radar site under investigation. I was the BEXR product manager and the GUI developer. I wrote the GUI Operator Control Software (OCS) in C using Microsoft’s Quick C IDE. The software directly used the Windows 3.1 C APIs to display application-specific windows, dialog boxes, target positions, and control buttons/lists. Compared to today’s GUI tools/API’s, it was the equivalent of writing assembler code for GUIs, but I had a lot of fun writing it. 🙂

The reason I decided to write this post is because I recently ran across a pack of sticky cards that we used to market the product and hand out at trade shows. It was a blast from the past….

It’s That Time Again….

…time to put my day-to-day responsibilities on hold and make my annual trek to New Orleans LA to celebrate Mardi Gras 2015.

At the time this post auto-publishes, I:

- will have arrived in NOLA with my best buddy Reno,

- checked in to the Crowne Plaza hotel on the corner of Bourbon and Canal Streets

- headed out into the night to join the party-goers on Bourbon St.

If you’re in NOLA anytime through Fat Tuesday, post a comment here or tweet me. Perhaps we can hook up for a fun time throwing and catching beads, eating cajun food, cruising the banks of the mighty Mississippi river, watching outrageously gawdy parades, and smiling our asses off. Life is too short for me to miss the greatest party on earth.

According to historians, Mardi Gras dates back thousands of years to pagan celebrations of spring and fertility, including the raucous Roman festivals of Saturnalia and Lupercalia. When Christianity arrived in Rome, religious leaders decided to incorporate these popular local traditions into the new faith, an easier task than abolishing them altogether. As a result, the excess and debauchery of the Mardi Gras season became a prelude to Lent, the 40 days of penance between Ash Wednesday and Easter Sunday. Traditionally, in the days leading up to Lent, merrymakers would binge on all the meat, eggs, milk and cheese that remained in their homes, preparing for several weeks of eating only fish and fasting. In France, the day before Ash Wednesday came to be known as Mardi Gras, or “Fat Tuesday.”

Which Comes First?

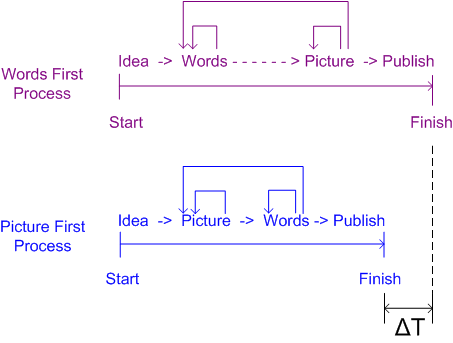

I get my blogging ideas from day-to-day observations, personal experiences, reading books and articles, and watching videos. There are two ways in which I proceed from idea to published post:

As the diagram illustrates, when I begin elaborating an idea with a picture first, I usually finish faster than when I start with words. I’ve also found that the picture-first process is usually more enjoyable. It just feels more fluid, less forced.

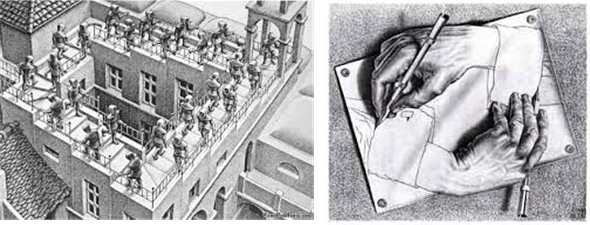

When I start drawing a picture, the act of sketching simultaneously draws forth some words that match the drawing as it evolves into being. Those words then beget changes to the drawing; and then the emerging drawing begets more yet more words associated with the changing picture. It’s an Escher-eque recursive process that drives me forward until at some point I simply decide to stop and queue up the post to be published. Unsurprisingly, when I write/test product code, I use the same picture-first process (sorry, but TDD is not for me).

I can’t count the number of times I started writing paragraphs of text and then stalled to a complete standstill when trying to concoct an accompanying picture. When that happens, I usually save the picture-less post to my drafts folder with the hope that when I revisit it again in the future a matching image will auto-magically appear in my mind. I have tons of picture-less posts in my drafts vault, but I refuse to publish a post without an associated picture. Some of those unadorned posts have hanging been around for years.

In the 1000+ post history of this blog, you’d be hard pressed to find a post that doesn’t have at least one picture in it. It’s simply just the way I operate. Maybe you should try it.

Make Simple Tasks Simple

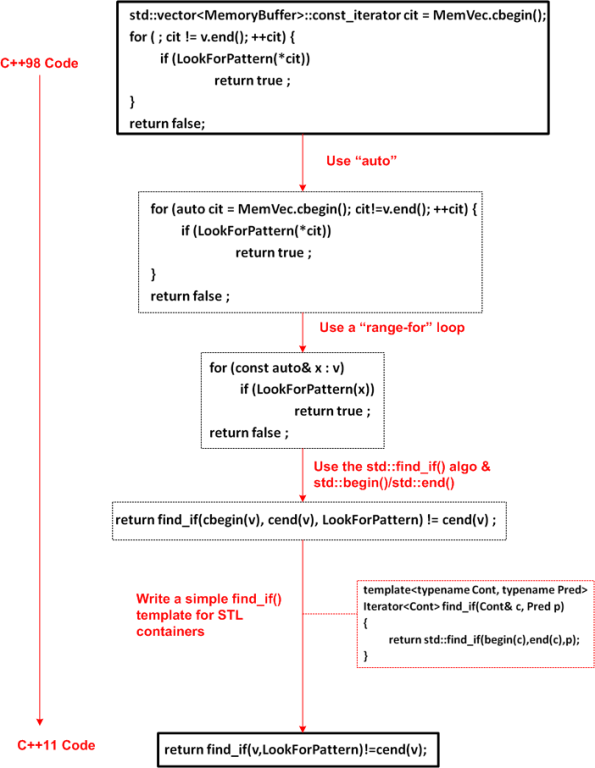

In the slide deck that Bjarne Stroustrup presented for his “Make Simple Tasks Simple” CppCon keynote speech, he walked through a progression of refactorings that reduced an (arguably) difficult-to-read, multi-line, C++98 code segment (that searches a container for an element matching a specific pattern) into an expressive, C++11 one liner:

Some people may think the time spent refactoring the original code was a pre-mature optimization and, thus, a waste of time. But that wasn’t the point. The intent of the example was to illustrate several features of C++11 that were specifically added to the language to allow sufficiently proficient programmers to “make simple tasks simple (to program)“.

Note: After the fact, I discovered that “MemVec” should be replaced everywhere with “v” (or vice versa), but I was too lazy to fix the pic :). Can you find any other bugs in the code?

Taking The Low Road

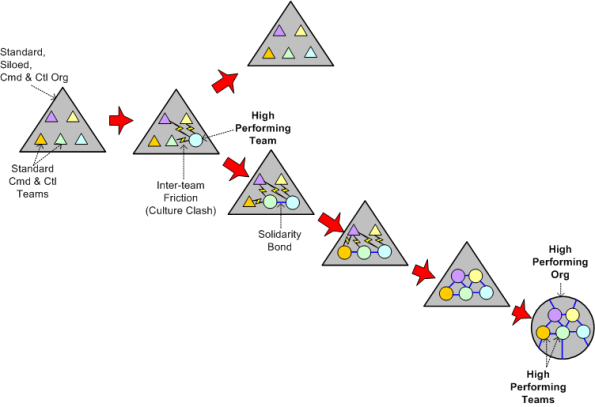

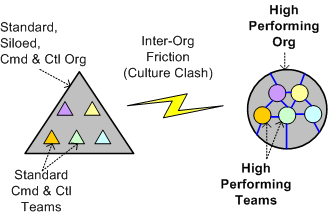

In the pic below, I prefer taking the low road over the high road.

So, now that you and your accomplices have labored long and hard to transform your standard org into a high performing org, you’re happy as a clam. Whoo Hoo!

But wait! What happens when you inevitably team up to do business with a standard org? D’oh! I hate when that happens.

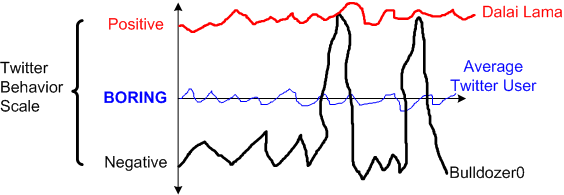

The TBS

What I’m Working On

Here’s a structured decomposition of some of the program’s stakeholders.

Now, all I gotta do is find out who the “product owner” is and invite him/her to our daily Scrum standup meetings. Better yet, I’m gonna hire an “agile scaling” expert to parachute in and guide the team to on-time, under-budget success.

As you can see from the following slide, the program is docu-centric. Not one, but three upfront plans? WTF! No problemo. I’ll just sit all the stakeholders down and convince them all that “traditional” documentation stuff is unimportant and so-yesterday.

To hell with any upfront requirements and design thinking and capturing, we’ll start TDDing our way forward, discovering what needs to be done as we go. From day 1, we’ll start delivering software in monthly increments for the entire 3 year duration of the program. We’ll simply mock out all the mechanical, microwave, and digital signal processing hardware so we can go faster than a speeding bullet – twice the work in half the time. Trust us, it’ll all work out – we’re agile.

Note: You can get the full deck of slides from FedBizOps.com.

Note: You can get the full deck of slides from FedBizOps.com.

Harvesting Your Dots

I never liked Dots. Every time I popped one into my mouth, I thought it might pull out a filling. But artistic dots, now they’re a whole ‘nother story.

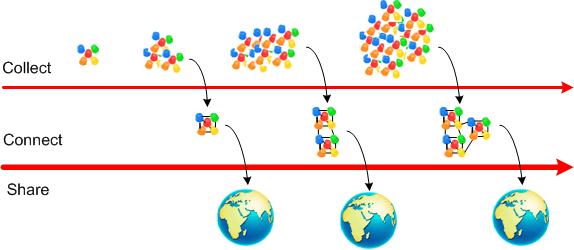

In “The Art Of Asking“, Amanda Palmer movingly writes about collecting, connecting, and especially, sharing personalized dot-connected products as follows:

Collecting the dots. Then connecting them. And then sharing the connections with those around you. This is how a creative human works. Collecting, connecting, sharing. This impulse to connect the dots—and to share what you’ve connected—is the urge that makes you an artist. If you’re using words or symbols to connect the dots, whether you’re a “professional artist” or not, you are an artistic force in the world. You’re an artist when you say you are. And you’re a good artist when you make somebody else experience or feel something deep or unexpected. – Amanda Palmer

If you think mining and connecting seemingly random dots is difficult, exposing the resultant products for all to see can be downright scary. The fear of rejection is always lurking in the background.

Amanda’s dotty insight reminds me of the greatest commencement address I ever heard – Steve Jobs’s speech to Stanford grads in 2005. In that inspirational talk, Steve chronicled how he unknowingly collected his dots over the years and then serendipitously connected them together into the idea that led to the birth of the world-changing Macintosh computer.

You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future. You have to trust in something — your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever. This approach has never let me down, and it has made all the difference in my life – Steve Jobs

I don’t know about you, but I feel like I’m full of… dots. I’ve got a boatload of dots hiding out in the deep recesses of my mind that are just waiting to be internally connected and externally shared. This blog is one catalyst for coaxing some of those cleverly concealed dots out of hiding, connecting them together, and sharing the result.

If you haven’t yet discovered the joy of mining, connecting, and sharing your personal dot collection, isn’t it about time that you made an attempt to do so?